1. Marisa Merz knit copper wire and plastic thread to make simple forms; she used the most basic stitch (knit, or plain stitch) and refused to purl. When you knit one row in plain stitch and the next row in purl stitch, you make a flat stretchy fabric, known as jersey, with a front surface (v-shaped stitches) and a back surface (wiggly stitches). When you knit only the plain stitch, as Marisa Merz does, there is no reverse, and the fabric you create has less definition: it is more flexible, and can stretch and pull in all directions. Certain orientations (front/back, top/bottom, left/right) dissolve or disperse, as the fluid form of the plain stitch proposes an open structure, looping the line.1

2. Marisa Merz knit copper wire into small squares, and placed them on the wall, gently stretched between small steel or copper nails. Here they produce unexpected geometries, circles in the spaces between. They might remind us of those copper scrubbers from the hardware store; they might remind us of the small and often useless cotton potholders that children knit in kindergarten. Knitting is described as using one-dimensional thread to construct two-dimensional fabric. Yet Marisa Merz’s knitted squares are not two-dimensional: they are not surfaces. On the contrary, they have a kind of expansive flexibility and a depth that gives them an airy material presence. They are like sponges, a form that mostly holds emptiness, and can soak up all sorts of things or feelings. They take up space, although they are so small. They stack. They do not lie flat.

3. Eva Hesse wrapped her sculptures, taking strands of cotton string and gluing them down to make a three-dimensional form out of a one-dimensional line. Here is a coincidence: two women making sculpture in the 1960s using a single line to make a three-dimensional object in space.2

Marisa Merz wearing her scarpette, L’Attico Gallery, Rome, 1975. © Claudio Abate/ Archivio Abate.

4. Marisa Merz knit small shoes out of translucent nylon thread, or copper wire. They look like they might fit a child, but stretched to fit her own feet. There is a color photo from 1975 of the artist, wearing her knitted shoes, looking out the window into the Rome night. We might imagine how her daughter Beatrice would delight in these small shoes, fairy slippers they both could wear. A black-and-white photo of the knitted shoes placed on the wet sand at the beach makes them look like they are formed from sea foam, or seaweed, calling to mind mermaids, sirens, and other creatures. There’s a magical quality to these small shoes, or shoe-ettes: they are called Scarpette, a plural diminutive of scarpa, which means shoe. They are like tokens or signs from another realm, the realm of storytelling, or the space where women and small children spend time together, exchanging words and making things. The imaginary.

5. In Italian, the word trama means weft, the threads interwoven across a fabric; it also means plot, as in the plot of a story, or a plot against someone.

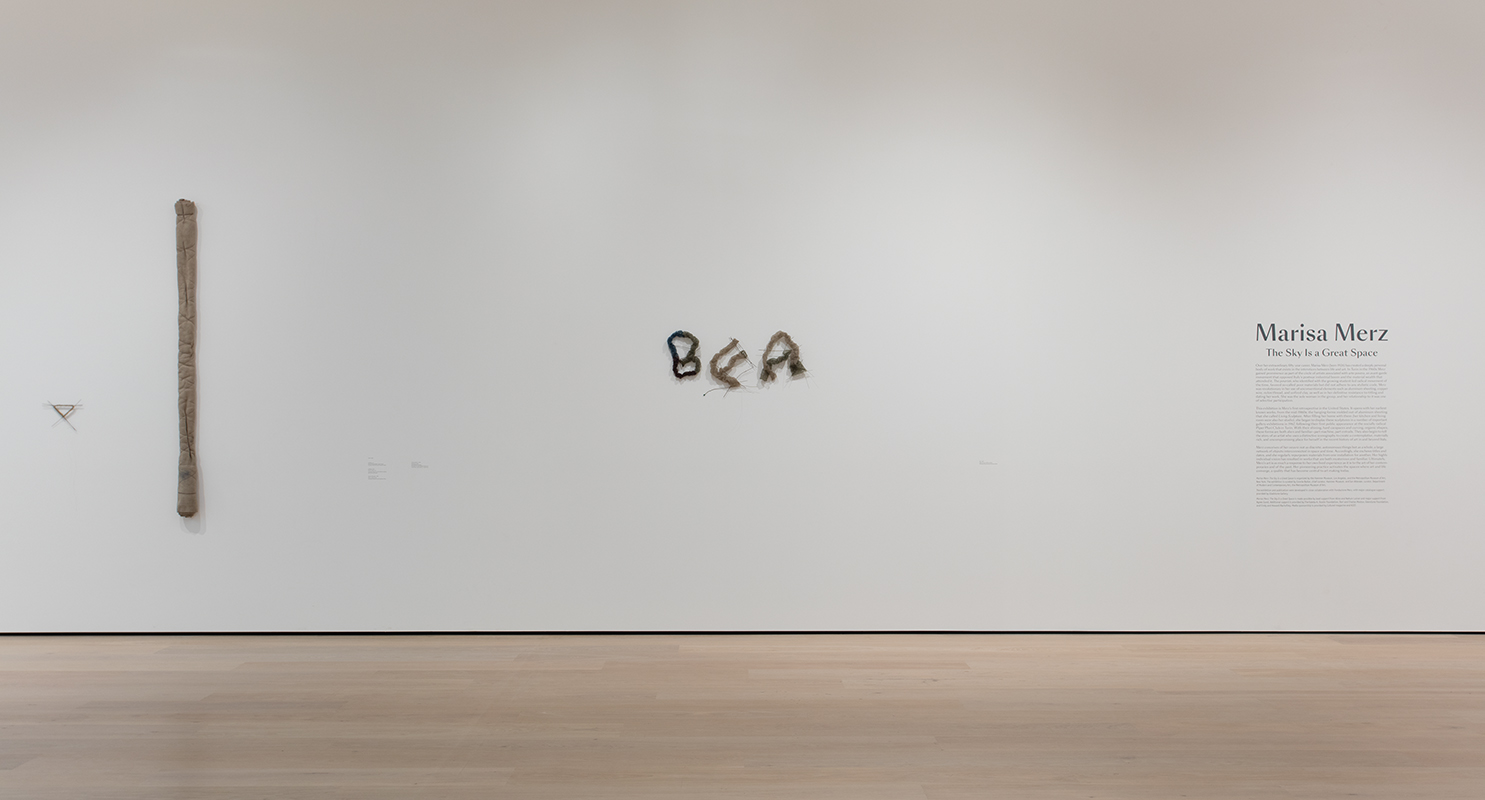

6. Marisa Merz also knit small, loose tubes, using three or four double-pointed needles. These too have an organic, undersea drift, like coral, or some other oceanic accretion. Sometimes she transferred the knitted tubing onto metal sticks, like stalks, or she simply left the knitting needles in. There’s more than one where the knitted material forms the name BEA, a diminutive for Beatrice. The knitted tubes are so simple they lack definition; they have a temporary quality: the tiny stitches could slip off the double pointed sticks easily; they could drift away into formlessness. They could unravel.

Marisa Merz, Bea, 1968. Nylon threads, metal sticks, 15¾ × 35 7⁄16 × 115⁄16 in. Courtesy of Archivio Merz, Torino. Photo: Brian Forrest.

7. There’s a kind of knitted patchwork that is made out of remnants: the leftover yarn not needed for sweaters or other garments made by hand. Just as those who make clothes will have scraps of surplus fabric that can be configured into patchwork quilts, so those who make woolen sweaters, or socks, or scarves, can use the excess wool to make small squares that can then be stitched or crocheted together into a blanket or throw. Old sweaters can be unraveled and reconfigured: knitted up again into something new.

8. The knitted work marks time: the time of making, and the reverie or wandering associated with home craft activities, day-dreamy time spent in a room with a child.3 It’s repetition time, marked by the repeated stitches, each blooming out of the last. When Marisa Merz leaves the pointed sticks and needles in the knitting, something else transpires: an attenuated, subtle note of aggression enters the field of meaning. It’s then that we remember that the fairy tale is not a happy story: it’s a story of kidnapping, loss, and transformation.4

9. There’s the silent girl who spent seven years knitting six sweaters out of nettles to rescue her six brothers who’d been turned into swans by their malevolent stepmother. She ran out of time, and at the crucial moment one sweater was still missing a sleeve. Nevertheless, she threw them over the swans, and they were all saved, transformed, though one brother lived on with a swan’s wing instead of an arm.5

10. When I was a child, my mad mother said, “You could use all sorts of things as a weapon if a strange man attacks you.” (I was six or seven, sufficiently childish to be struck by this scenario: under what circumstances…? My mother never explained—anything.) She said, indelibly, “Remember, you can always use a pencil to stab him in the eye.” (Or a knitting needle.)

11. Marisa Merz made a swing for her daughter Bea that hung inside the house; it took the form of a slanted wooden platform with a pointed edge. A child would slide off it, or struggle to remain seated on it; any swinging would run the risk of the pointed corner sinking into whoever passed by. It is perhaps less a swing than a ride, a suspended seesaw. Like the knitting needles, there’s a frisson of danger. It is the opposite of a safe toy: it is a sculpture and also a difficult, risky, and exciting proposition.

Marisa Merz, Altalena per Bea, 1968. Wood, metal hooks, dimensions unknown. Courtesy of Archivio Merz, Torino. © Paolo Pellion.

12. Copper is a flexible conductor of electricity, representing the possibility of distant connections, or shocks. Copper fuse wire is familiar in European houses, where electrical systems are much more hands on. Knitting small squares with copper filament pulls in both directions: toward industry, electricity, technology—what we used to call the great outside world—and at the same time toward the domestic, marked as feminine. With the copper wire, the translucent nylon filament, and the heavy aluminum foil, what emerges in this work might be an aesthetic of industrial femme, undoing the cascade of antinomies that places knitting on the side of the woman, and the flow of electrons over there with the factory and technology.6

13. Marisa Merz, “Come una dichiarazione” (Like a declaration), published March 1968:

I do not respect Johnson, I do not respect the masters.

I am not available any more, because I want to begin all over again.

I could still be available to a child, but not to a man, no.

If a man asks me to do something, I do that thing the way I want…7

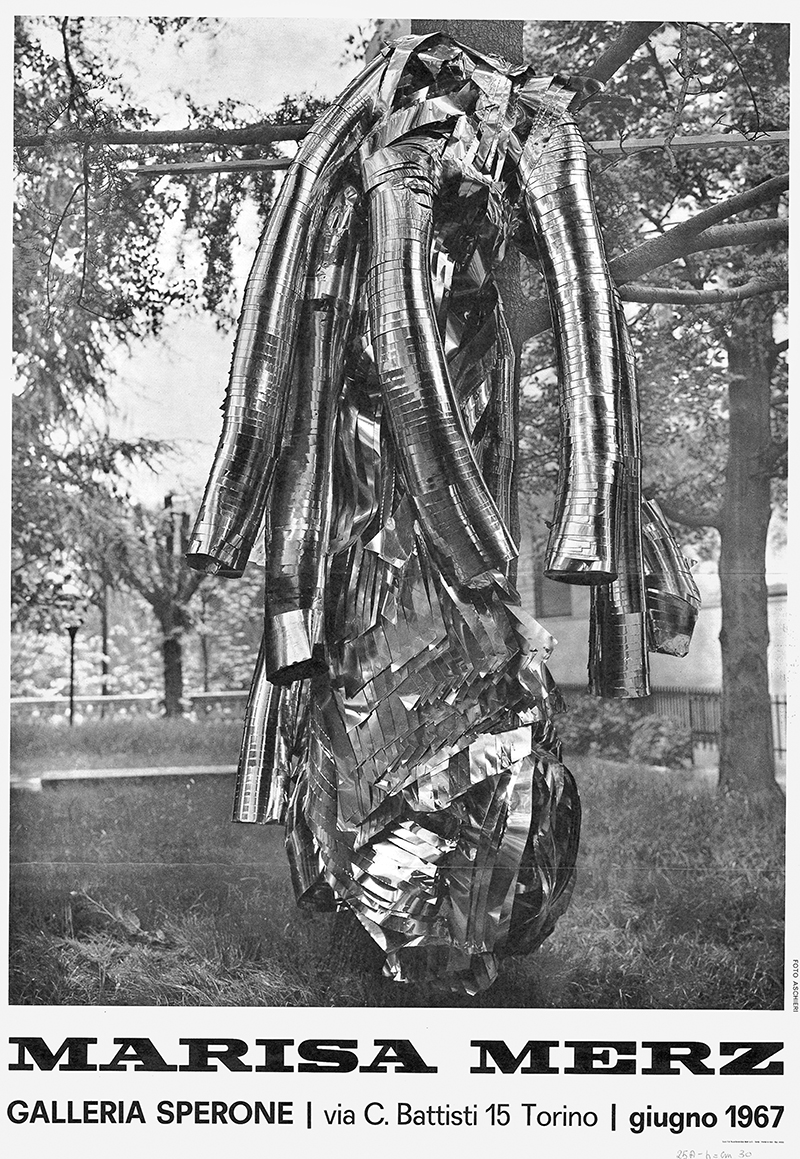

14. In 1967, Marisa Merz made a black-and-white, silent 16mm film, La Conta (Counting), showing the artist in her kitchen in Turin, opening a can of peas and then counting each one. The kitchen is dark; the counting measures time. There is a silvery slinky metal sculpture looming in the darkness. Marisa Merz silently counts the peas.

Marisa Merz, La Conta, 1967. Video still. 16mm film, black-and-white, silent, 2:44 min. Courtesy of Archivio Merz, Torino.

15. The big works from the 1960s, the silvery metal things hanging from the ceiling, are all called Living Sculpture. There’s a bunch of them, a disparate set of different iterations. They are each made out of strips of heavy, industrial-grade metal foil, a more substantial version of the aluminum foil we use in the kitchen to wrap leftovers. Marisa Merz cut the foil into strips and wound it into tubular forms, stapling the strips together with an industrial stapler. The tubes pour and spill, opening up like an accordion, unfurling like a natural thing. Looking up at these suspended sculptures, the forms unwind, like duct work gone organic; they are bulbous, like garlic or mushrooms, like the involute and convolute whorls of the nautilus shell. Do they also fold up, like a paper fan?

16. Dressmaking verbs: crush, crease, crinkle, pucker, ruffle, frill, ruck, shirr. Furl. Long tubular metal ribbons hang in garlands, and momentarily the folds and swoops become baroque, a fashion statement. These metal flounces are pleated, tucked, gathered. The metal ribbons are sleeves, or stems, or roots. It might be the view of a hedgehog, looking up at flower bulbs, onions. It’s the view of the depths under the city, the crazy tubing that makes all the systems run.8 It’s visceral in form, intestinal, the first and last ductwork. It’s the stuff that’s inside somehow appearing on the outside. These sculptures reflect light in all directions.

17. Marisa Merz took a flat sheet of shiny metal and cut strips out of it, using giant scissors; she laid them over each other, forming shapes. I imagine she wrapped them around something: a ball, a tube, some piece of her household furniture. Her thighs? She stapled the strips together, building them out like the ridges of a shell. Then she tied them into groups, using simple cotton ribbon, what in England is called tape. One uses tape to sew hems, to bind raw edges, to tie a parcel. The knotted tape is briefly visible: in the museum, some of these metal sculptures hang from loose loops of cotton tape, of different lengths, others from transparent nylon or steel filament. The loops of tape are usually off-white, though in the conserved version, belonging to the museum in Turin, the tape is black.9

Marisa Merz’s Living Sculpture pictured on the invitation card for an exhibition at Galleria Sperone, Torino, June 1967. © Paolo Bressano. Courtesy of Archivio Merz, Torino.

18. The one that’s been conserved is extremely reflective, like mirror; others are dully metallic, and some retain traces of the greasy dust that accumulates imperceptibly on kitchen surfaces that are out of reach. Marisa Merz stenciled flat flowers in primary colors on some of them, reminding me of the floral patterns of folk art and 1960s wallpaper, and Warhol’s flowers too.

19. The huge hanging sculpture is temporary: this configuration today, but rehang the thing and the configuration will shift, it has to. Time is built into it, an element both uncertain and provisional. These sculptures are light and heavy at the same time, both easily crushed and resilient. They are handmade, organic, embodied, and somehow plant-like, while being industrial, duct-like, manufactured metal. And the incremental accretion of the stapled metal strips is like bandaging, another spiral wrapping and looping of a line.

20. The metal forms are rhizomes: they are interconnected, without hierarchy or grid. They are alive and they reflect light, moving gently with the air. A photograph from 1967, which was used for the invitation card for her show at Galleria Sperone, in Turin, shows some of them suspended in a tree.

21. Living Sculpture hung in clusters in the Merz apartment, appearing in the kitchen, the hallways, the study. There are photographs of the television almost swallowed by the metal forms. There are photographs of the tubular structures emerging out of the kitchen ceiling, like the secret parts of the house squelching into view. It’s the return of the repressed: something the domestic scene hides has come out to play. It’s the metallic fungus that goes on growing and won’t be eradicated. It’s the other time/other space thing, a glimpse of a secret world.10

Marisa Merz, Living Sculpture, 1966 and Mario Merz, Fibonacci Santa Giulia, 1967. Installation view, casa Merz’s kitchen, Turin, 1968. Courtesy of Archivio Merz, Torino, © Paolo Pellion.

22. There’s a measuring of gravity that occurs in our bodies when we witness the ways the metal forms are thrown into space. Shiny tubes and bulbs fall, yet they hold their shapes, they resist gravity, like us. The plunging forms drape, like our clothes, or an eighteenth-century wig, silvery metal ringlets. Looking again, I remember her little shoes, and the way knitted fabric rests against the surface of our bodies, another skin.

23. Reflection: in the bright reflective surface of the metal sculptures, immateriality and materiality coincide. It’s as if the shining metal becomes liquid, turning into light. In 1969, Eva Hesse suspended fiberglass threads from multiple ceiling hooks, making a sculpture that dissolves into light. It’s called Right After. Here is a coincidence: two women in the 1960s making big suspended sculptures that lose their weight and materiality to become light, while remaining metal, or fiberglass.

24. My daughter said: “If you leave me alone in the house with the child, when you return you will find giant silvery guts pouring out of the kitchen ceiling, and tiny fairytale shoes knitted out of reflective metal thread, shiny in the light. When you leave me alone in the house with the child, I will open a can of peas in the dark kitchen and carefully count each one while she sleeps. When you leave me alone in the house with the child, I will make a series of pictures of women, each one like the one before. I don’t want to go out, anyway. I’d rather stay home.”

25. Marisa Merz took old thin grey cotton blankets and rolled them up into tubular shapes; she tied the rolls with nylon thread or tape. Then she went down to the beach with her much more successful and renowned artist husband Mario Merz. Mario carried the rolled blankets over his shoulder; he threw them down onto the wet sand, while Claudio Abate took photographs. Something flat becomes tubular; something that is almost nothing becomes a strange offering to the gods. The tied blanket is like a fish, or a piece of driftwood, lying on the wet sand.

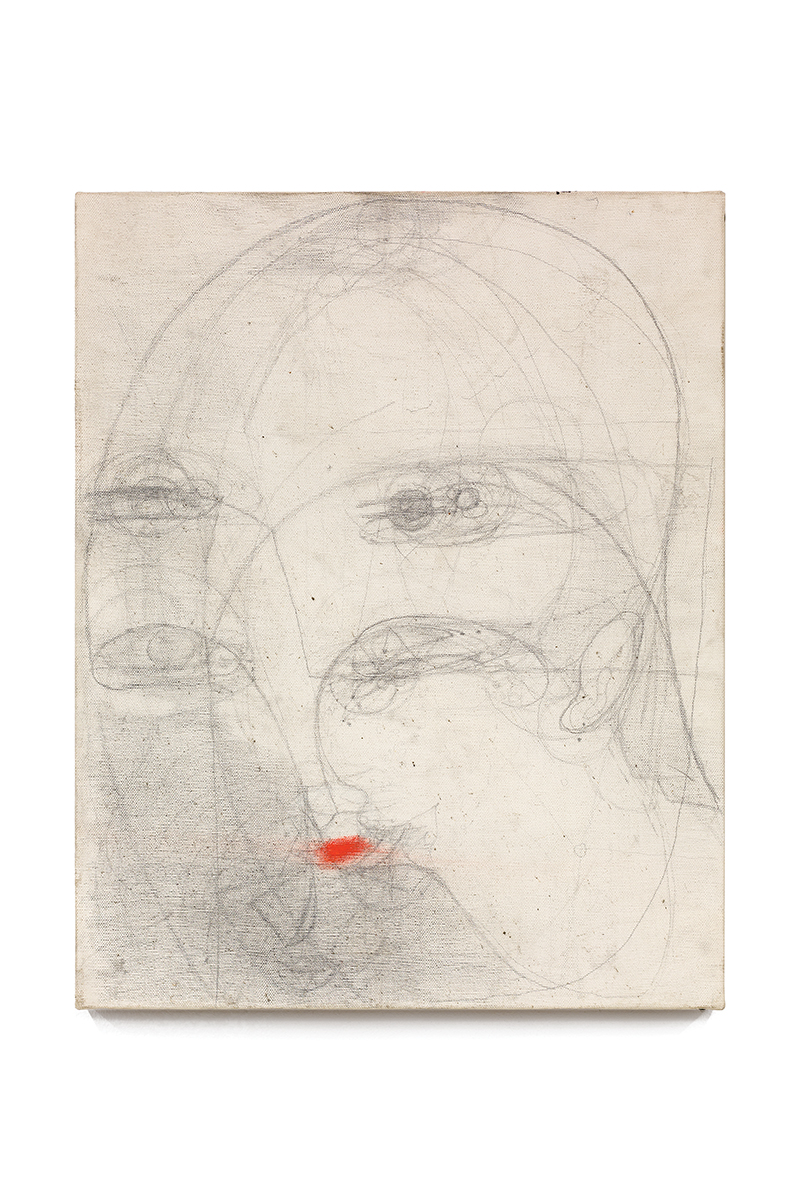

26. There are also works on paper, on canvas, mostly drawings of women’s faces. Here a pencil line meanders back and forth on the canvas, reminiscent of the knitted line of wire. A loose netting of lines over these heads suggests the drawing was slow, taking an indeterminate time to make; it suggests there was no model, no observation, rather a drawing from the imagination. The drawings employ a familiar mid-century dreaminess—meshwork of the afternoon—but Marisa Merz did so many of them, she must have meant it.

Marisa Merz, Untitled, n.d. Graphite and lipstick on canvas, 19 11⁄16 × 15 ¾ in. Courtesy of Archivio Merz, Torino. Photo: Renato Ghiazza.

27. How to account for these faces, so many of them over the years, and most of them with no title, no date? Some are big; many are small; they are repetitive, insistent, they resist interpretation. Are they self-portraits, or something else? An evocation of the anonymous woman (anonymous was a woman, Virginia Woolf wrote), that nobody in particular who seems to be stuck on repeat.11 Through these drawings, we sense her erasure, reiterated, as well as her lack of definition, her tenuous identity, and her persistence in time. She’s always already almost formless, yet always also recognizably a woman, and very clearly undefined. In other words, she’s a paradox, living out the contradictions, like the rest of us.

28. Some of the drawings of girls’ faces are large, square, almost like an album cover blown up. Marisa Merz’s use of elements from commercial art speaks of the ways we are haunted by advertising, album covers, movie posters, billboards. As my friend said of one, “It could be a Campari ad.” Marisa Merz does these faces over and over, for decades; she really meant it. What did she mean? I imagine she meant to say something like, hey, hi, you know, being a woman in Italy, or anywhere, in 1962, or 1979, or 2012, is inevitably and deeply and inextricably connected to Campari ads. No apologies, no drama, no protest. Simply the facts.

29. The women’s faces in some of her drawings lean towards cliché, they seem empty and flat, with their lacy net of lines overlaid. Does that make femininity empty and flat? Sure. It’s a constant struggle (for us girls) not to fall into cliché, but here the fall is enacted over and over again. Is that what Marisa Merz meant? Is that the space she invites us into?

30. The repetition of the faces points back towards the knitting: a kind of repetitive time, where you keep doing the same thing, over and over again, with slight variations. It’s a psychic space where all sorts of things can pop up, treasures from the deep. (Years ago a friend insisted that the endless re-typing of our writing that we used to do, before we had computers and printers and word processing programs, was actually incredibly valuable because it was inside and within the sheer tedium and repetitive act of re-typing that the best ideas broke through.)

31. When I was seventeen I split up with my first boyfriend, and shortly afterwards my best friend came over to my house with needles and a ball of yarn, to teach me how to knit. She said, “I’ve come to teach you how to knit, because you need to think.” And we are still friends, despite and because of this.

Marisa Merz, Untitled (part.), n.d. Unfired clay and metallic paint, 3¾ × 5 1⁄8 × 3 1⁄8. Courtesy of Archivio Merz,Torino. Photo: Renato Ghiazza.

32. Marisa Merz’s clay heads, like the drawings, are repetitive, uncommunicative, and somewhat obtuse. They sit in silence. Occasionally they’re funny, but much of the time they’re elegant or ugly lumps, molten. Marisa Merz made the heads with a single gesture, and then poked some eyes or a mouth into the shape, as if to say, there: a head. A human being, in its most reduced form. A woman. Almost nothing.

33. This is Lucy Lippard quoting a close friend of Eva Hesse: “Grace Wapner recalls that around this time Hesse found some object in the street—a broken pipe or something—which made an immense impression on her; she called it a ‘nothing’ and said that what she wanted to make was ‘nothings’…”12

34. The ceramic heads are made of unfired clay; if you drop them or knock them, they will turn to dust. Marisa Merz arranged them with their formless faces on a steel table, recalling Giorgio Morandi’s paintings of vases and jars, or those stones from the beach arrayed on my windowsill. Or she placed them on the floor in a square lake of paraffin wax, three meters by three meters, as if slowly drowning or floating. Sometimes they are carved out of marble. Tacita Dean described how the heads are found propping open doors in the apartment where Marisa Merz lives.13 They may have gold leaf pressed onto their surfaces, or copper netting. They are part of the landscape of the house, her familiars.

Marisa Merz: The Sky Is a Great Space, installation view, Hammer Museum, Los Angeles, June 4–August 20, 2017. Photo: Brian Forrest.

35. Among the collaged works on paper that mostly seem to represent angels and Madonnas and girls, there is one that shows a printed black-and-white photo of the face of Renée Jeanne Falconetti, in Carl Theodor Dreyer’s The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928). Her face is raised in a quiet anguish, her eyes half closed. Some of the clay heads repeat this position: heads tipped back, their faces lifted for who knows what kind of ecstasy. Dreyer’s Joan of Arc consists almost entirely of extended close ups of Falconetti’s face as she is interrogated, tortured, and eventually executed; like Lillian and Dorothy Gish, Mary Pickford, and other great silent film actors, Falconetti understood that the film’s power lay in the complex unfolding of distinct emotions, moving across her face. When I saw it, it was clear that this stunning film was devoted to what one might call the Spectacle of the Suffering Woman. I then realized that most films are constructed around this spectacle: the visualization of a woman in states of fear, loss, sorrow, shame, humiliation, distress, misunderstanding, torment, and/or as a victim of violence. When we’re not being Campari ads, or mad mothers, it seems we find ourselves in Falconetti.

36. These artworks belonged to the place where Marisa Merz lived and lives still, an apartment overlooking the market square in Turin; they are, perhaps, out of place, displaced, in the museum or the gallery. And the artist parted with some of them reluctantly, as if their meanings and resonance would change when they went out into the world for a year or more, to star in her retrospective. Certain things she refused to let go: the curators describe how they would put together a stack of drawings, and then go to lunch; when they came back, some of the drawings would have been withdrawn, taken back by the artist.14 She would not let them leave the house; at her great age, it would appear that Marisa Merz cares more about her lived reality within the house and the studio than she cares about the museum show, the retrospective.

Marisa Merz with Living Sculpture, Torino, 1966. Courtesy of Archivio Merz, Torino. © Renato Rinaldi, Milano.

37. These artworks are part of a series of installations that Marisa Merz made inside her domestic spaces, in Turin, in Milan, and only an approximation of their meanings or effects can be achieved by isolating the individual works and putting them on display in the museum’s vast white rooms. So many works have no title, no date, as if at a certain point the artist figured out a simple way to undo the historical record, to challenge the implied narrative of artistic development. This disregard for the significance of the archive, and the demands of the curators, underlines Marisa Merz’s interest in something other than her place within the history of contemporary art. Yet these works are all about time, and clearly Marisa Merz values her own lived time—the relatively short time remaining to her. She cares deeply about moments unfolding in space, about simultaneity; she cares about the ways material forms can contain and imply different temporalities. Still she doesn’t give a toss for the official history: she will not submit to that imperative.

38. For some years now, Marisa Merz has refused to allow herself, or her studio, to be photographed, or her voice to be recorded. There are people who find this beguiling, a kind of witchy eccentricity. They say things like she doesn’t like machines, as if she’s a medieval saint, or a madwoman. Then they show a photograph of her studio (that was apparently taken without her permission) and it contains a shiny new microwave oven.15 There’s another way to approach these questions, which is to ask, reflectively, why would a 91-year-old artist refuse to be photographed? Could it really be mere vanity, or some kind of phobia about machines? (If industrial femme means anything, it means that in some sense she makes her own machines, no?16) My surmise is simple: being in touch with reality, Marisa Merz recognizes that she is near death, and she’s decided that she doesn’t want her recorded image, or her voice, to be available for infinite dissemination through the Internet, for post-mortem devouring. Possibly she thinks the photographs of her as a younger person should be sufficient proof that she existed. Perhaps she wants her voice to be something remembered by people who actually knew her, rather than accessed digitally by strangers. Her artwork is about embodiment, materiality, intimacy; controlling how close the world can come to her embodied self is a losing battle; she continues to say no, nevertheless.17

Marisa Merz, O sulla terra (O on the Ground), 1970. Woven nylon wire, knitting needles, exact dimensions unknown. Photo documentation from the action at Fregene. © Claudio Abate/ Archivio Abate.

39. When I saw Marisa Merz’s show at the Met Breuer in New York, it was deep winter, very wet and cold. The trapezoidal windows that protrude from the façade on the north side of the building had odd little sacks placed within them, resting up against the glass. Like cousins of the wrapped and rolled blankets lying on the wet sand, their purpose was to soak up the rainwater that slowly seeps into the building through the leaky windows. In the past, Marisa Merz would call up the presence of the sea by placing a bowl of water, or a small bowl of salt, in the gallery. Here the elements joined the conversation as if invited to take part.

Leslie Dick lives in Los Angeles.