The Dash column features creative nonfiction writing about art and its social contexts. The dash separates and the dash joins, it pauses and it moves along. The dash is where the viewer comes to terms with what they’ve seen. In what follows, writer Sabrina Tarasoff presents a meditation on The Prototype, Josef Strau’s gouged tin images of angels, on view at Gaga Reena from April 6–June 15, 2019.

OutKast, Prototype, 2003. Video still.

Forgive me, theory, for I have sinned. I truly believed that, confronted with Josef Strau’s argent paintings of angel silhouettes, I would turn straight to Walter Benjamin like a good acolyte of the Frankfurt School, and think deep about the impact of iconography as it adapts and absorbs time and ideation—because, you know, historical materialism. I was convinced that sights of death, art world agnosticism, and culture perishing in overproduction would underwrite this thought process, and that I would manage to summon the subject of self-similar narratives vis-à-vis culture’s reconciliatory meaning-making. I was going to quote Wittgenstein—that bit on how “the purely corporeal can be uncanny”—and maybe lift something smart out of T.J. Clark’s new book Heaven on Earth. Because like Marina Warner noted in her lectures on myths, I too believe that “the fictions and narratives of a society contribute as fundamentally to its character as its laws and economy and political arrangements.” Holding myself to the holy standard of critical thought, I set off piously circumventing any reference to the personal, the mythos of love, first contact, ineradicable impressions, hope, belief, and paragons of virtue. As if we don’t all need those things, desperately.

Installation view, The Prototype, Gaga Reena Fine Art, Los Angeles, April 6–June 15. Courtesy of the artist and House of Gaga, Mexico City.

Instead, starry-eyed from my time in the French countryside, a quick online search lead me astray and I wound up listening to “Prototype” by OutKast for three weeks on repeat, sadly—or perhaps not—growing evermore convinced that the only truly righteous philosophenweg was found in wavy R&B. In the music video, “extra extraterrestrial beings” from planet Proto land on Earth, mingle with a local, and encounter “the rarest of all human emotion. Love.” No doubt a visual study of acceptance, love of otherness, and an embrace of difference, the video’s theme of first contact grants cosmic license to the power of being moved, touched, affected. In other words, the “prototype” is science-fiction for bleeding hearts, written for those of us who still have room in our sapiosexual (or is it semiocapital?) heads for that spaced-out, alienated thing called romance. OutKast’s prototype, in this sense, is a saccharine embodiment of the alien desire to reinvent love (whatever that means) over and over, even, or especially, as it loses specificity in a world of power and desire. I said no theory—but no Love without Lauren Berlant, as she mulls over images of love on her blog—so:

Aggressions and tenderness pop around in me without much of a thing on which to project blame steadily or balance an idealization. So it’s just me and phantasmagoric noise that only sometimes feels like a cover song for a structuring shape or an improv around genre. In love I’m left holding the chaos bag and there is no solution that would make these things into sweet puzzle pieces.

Installation views, The Prototype, Gaga Reena Fine Art, Los Angeles, April 6–June 15. Courtesy of the artist and House of Gaga, Mexico City.

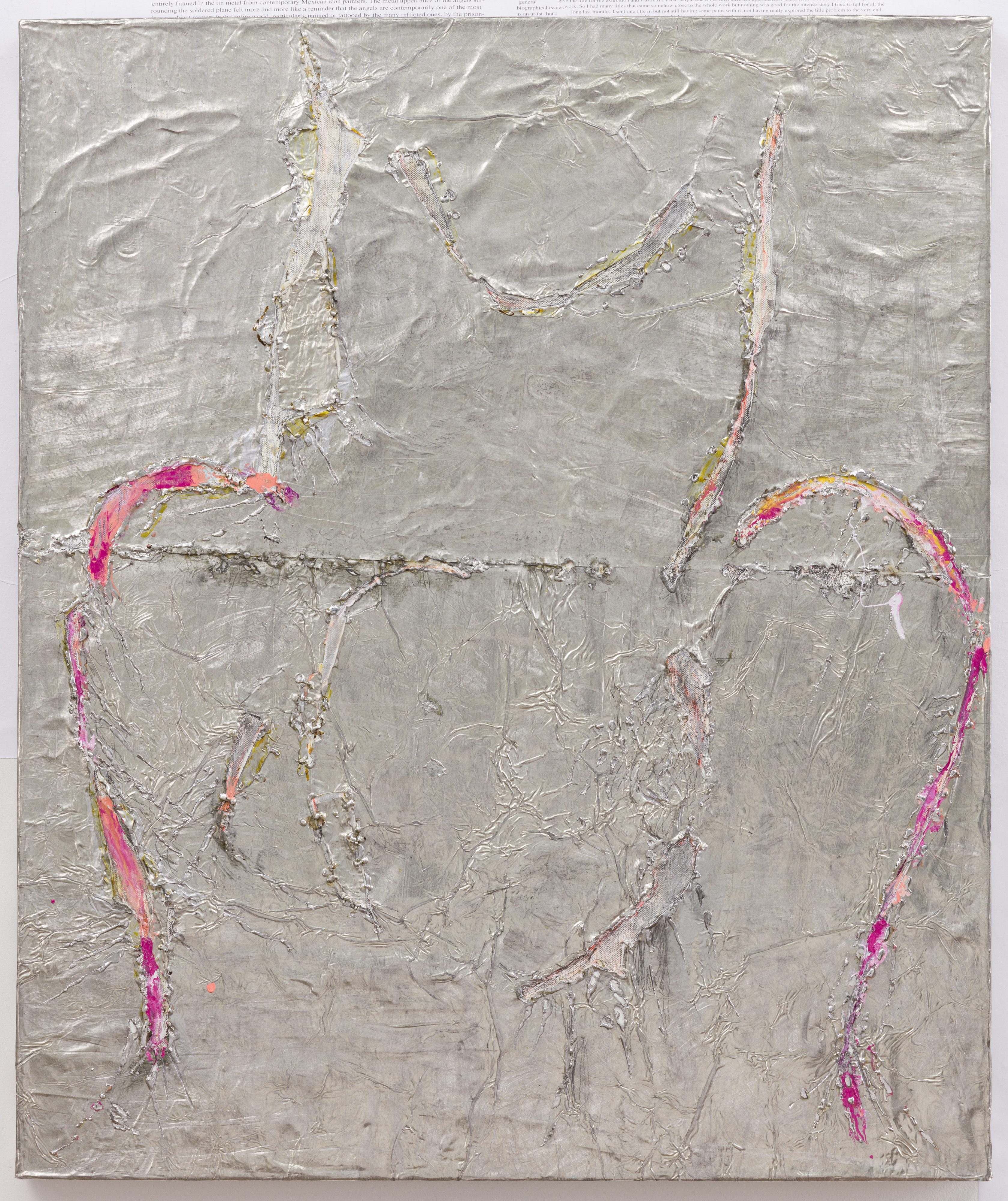

Love is chaos, a burst: an instance of breaking or splitting as a result of internal compressions and pressures. (I think I ripped that off from the dictionary.) No doubt, then, the image of first love—or the first love of an image—pushes us into our “external imagination,” as Josef Strau wrote, “into another world, or possibly behind.” The paintings are variations on the same image, an angelic contour culled from 14th century iconographer Theophanes, scratched out of a canvas clad in wrinkled tin. Call it a really affective alien, first love, an angelic icon, or some phantasmagoric noise to keep your idealized attachments company. The prototype provides first contact from which we can draw out a sequence of dreamlike images—and do so in the good grace of seriality’s monogamous lull. Not to mention a suspension of disbelief in certain institutional fictions. For Strau, the Prototype paintings began from an early desire to paint an angel, “because it is the guardian above the bed of a child. It could be the first image they see.” He searched back in history for a trite image that hit home, created art in its shimmering likeness, then stepped back to mull over what future renditions might “demand.” Like more of the same, more rehashing of the same lines, more suspended disbelief, relapsing over and over again into an original image that cannot ever truly be redrawn. Why? Because there is pleasure to be found in repetition. Or, in other words, those in love are prone to masochism.

I hope that you’re the one

If not, you are the prototype

We’ll tiptoe to the sun

And do things I know you’ll like

Many have tried to adequately capture Strau’s aesthetic fragility by pinpointing the artist’s unsettled commitment to the signifier—or its flimsiness, on par with our mortal coils. Joanna Fiduccia, for instance, wrote that Strau’s works seem to be “quivering with connection,” aptly capturing the desiring flutter of those etched angelic silhouettes. Angels exist in our popular imaginary as figures to be touched by, mostly represented, as Strau himself wrote, “by the many inflicted ones, … those intensely seeking and praying for relief and charity.” To repeat the image of the angel is to repeat its gesture of forgiveness, i.e. imbue one’s practice with the heavenly—albeit idealistic—assurance that whatever image appears will be an icon of pardon. As Strau put it, one is given “angelic license to paint them,” which, put another way, is angelic license to indulge in the idea of lovingly absent-minded forms of labor, no closure necessary. What those heavenly icons gain in redundancy is the pleasure of production, kind of like the pleasure of tiptoeing to the sun with your alien paramour, or being held captive under first love’s uncanny effect. It absolutely lacks logic and sense. In fact it closely resembles certain raving hallucinations and grandiose pretensions courtesy of highly questionable ideological structures. But—believing in improbable images is also a way of allaying the constant mitigation of emotional risk we subject ourselves to in this technologically ordered world. Skeptical as one may be of their tinfoil optimism, the angels imagine a future propelled by expectancy, cue Julia Kristeva: “painfully sensitive to my incompleteness, of which I was not aware of before.” Love sucks.

Josef Strau, 16, 2019. Tin, solder, enamel and marker on canvas, 26 x 31 inches. Courtesy of the artist and House of Gaga, Mexico City.

Think of Elaine Scarry, whose entire introduction to On Beauty and Being evokes similar whiffs of desire, hope, repetition, and recurrence, i.e. the sunny pleasures of said prototype’s soft protrusions into the now and beyond. She too sees an image, or object—or “beautiful boy”—and hopes to settle into the experience of cognition at the moment beauty appears. “Beauty,” Scarry wrote, “brings copies of itself into being. It makes us draw it, take photographs of it, or describe it to other people. Sometimes it gives rise to exact replication and other times to resemblances and still other times to things whose connection to the original site of inspiration is unrecognizable.” On one hand, the act of copying signals attachment. On the other, it detaches. To recreate is to move away from an original, to allow enough space for its symbolizations to shift. Iconography makes meaning an ongoing negotiation, a compromise between image and ideology. Something might happen if you let yourself dissociate from your objet d’amour—like entering into a bedazzled mode of being where whatever emptiness, alienation, or out-of-placeness you feel ripples away from the stable image. Serial repetition pushes against power in its belief in the surreal, the open-ended, the undecidable—in love—on Kristeva’s terms: it is “a true process of self-organization.”

Installation view, The Prototype, Gaga Reena Fine Art, Los Angeles, April 6–June 15. Courtesy of the artist and House of Gaga, Mexico City.

What comes across in Strau’s exhibition is a contemplation on how alien it can feel to look at an image or a person, even if we’ve seen them a million times before; how a familiar sentiment, a sugary gesture, an artistic exercise, can become unexpectedly strange when we indulge in likenesses, doubles, mirrors, or replicas. In a sense, this is a basic problem of representation, and to how meaning evolves across icons. (This is also the permanent crisis of lovers, but I’ll leave that alone for now.) What Strau adds to the occasion is patience, commitment, and a genuine sense of attachment to the content. Not necessarily angels, which seem to mostly function as conceptual placeholders for some secret subject about images we fall in love with and try to live through. Envisioned from deep within rural France, set to the sound of André 3000’s amatory discourse—I hope that you’re the one—while mulling over how something as chaotic as love finds (temporary? inadequate) form in our productions (infuriating!), Strau’s angels glint with aesthetic possibility found in the loving gesture of visual and psychic transference, even if the logic of holy secularism doesn’t quite hold up. “Neither denying the ideal, nor forgetting its cost,” as Kristeva once wrote, he allows his images to be both fragile and filled with meaning, both undetermined and cosmic. No futures are foreclosed, however speculative, sparkling, or banal. Godly or secular, the angel in popular myth is a visitation of light, a psychic space that promises variance, change—or, on OutKast’s terms: a reminder to “do sumn’ outta the ordinary. Like catch a matinee.” If not, you are the prototype.x

Sabrina Tarasoff is a Finnish writer living in Los Angeles.