For the re:Research series, we invite artists and writers to present the underpinnings of their work. Here, Melanie Nakaue traces a through-line from the earliest digitally-modeled human figure to the elaborate simulations of the present, suggesting that 3-D animation holds special potential for reimagining the constraints of the self.

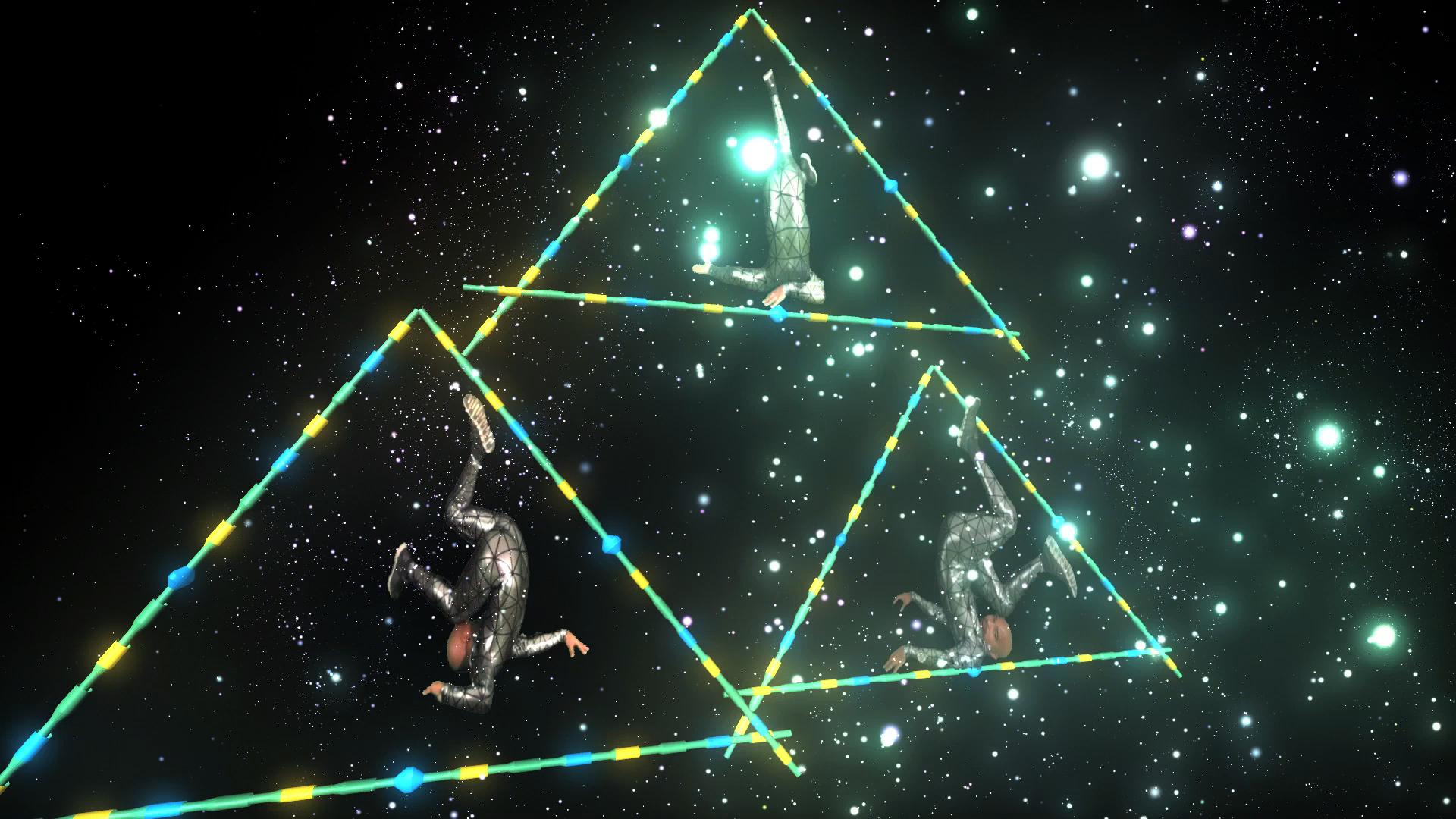

Jacolby Satterwhite, Reifying Desire 5, 2012. Video still. 3-D animation and video with sound, 8:47 min. © Jacolby Satterwhite. Courtesy of the artist, Electronic Arts Intermix, New York, and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

The computer’s evolution into a tool for artistic production took a leap forward in 1968 when William Allan Fetter, a graphic designer who worked for Boeing, created one of the first computer-aided drawings of a human figure (a pilot). Fetter’s process of plotting or “drawing” his model in various positions successfully simulated, for the first time, a human figure in three-dimensional digital space. Today, the possibilities seem endless. We can simulate and create virtual environments and objects with 3-D animation, resurrect antiquities of the past with 3-D modeling technology, and create immersive experiences with the use of virtual reality (VR).

To fashion a likeness before the advent of photography, an artist had to paint a portrait or sculpt a figure. 3-D animation conflates the properties of traditional media. Modeling objects, textures, and materials requires the facility of a sculptor. Visual elements can be animated as still images (frames) that are later put together in a sequence for the illusion of motion. A scene within a 3-D animation could use a high-dynamic-range image (HDRI) to mimic the nature of light and its reflective or luminous properties as it scatters across a complex 3-D scene. Using technology for art production, 3-D animation may eclipse the mediums produced by modernism to provide the artist with tools to explore the varied social and political contexts introduced by the simulation of space and bodies.

Left: Katie Torn, Low Tide (triptych comprising Gremlin, Mermaid, and Squid), 2017. Three-channel video installation. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Mario Gallucci. Right: Katie Torn, Mermaid, 2016. From the triptych Low Tide, 2017. Digital animation on monitor. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Mario Gallucci.

In Low Tide (2017), a three-channel video installation by artist Katie Torn, the use of 3-D animation bridges the simulation of the female body and the connotations of its representation throughout Western art history. Low Tide comprises three videos on monitors (from left to right, Gremlin, Mermaid, and Squid) hung in a vertical, or “portrait,” orientation, and referencing painting’s canonical triptych compositional strategy. The frame of the flat-screen monitor also acts as a frame for each video, delineating the boundaries of the visual field, and thereby relating it to the pictorial framing of a canvas.

The formal presentation of Low Tide is a direct critique of the hegemonic construction of the female body. In Gremlin and Squid, the figure is implied through an assortment of 3-D objects such as flowers and toys, and spews aqueous liquid. The body is a receptacle and a commodity. In Mermaid, the doll-like figure with its sickly white, stucco skin flips the hypersexualized image of femininity into a grotesque physical construction. This recalls the cultural detritus such as newspaper and magazine clippings that assemble the figure in Dadaist Hannah Höch’s 1920 piece The Beautiful Girl. The disparate 3-D models and elements of consumer culture that comprise the figures in Low Tide, including a milk carton and a VHS tape, reference the commodification of the female body in popular culture and in art history. Torn uses the medium to reflect on the artifice behind gender representation: everything we see is a construction, a simulation.

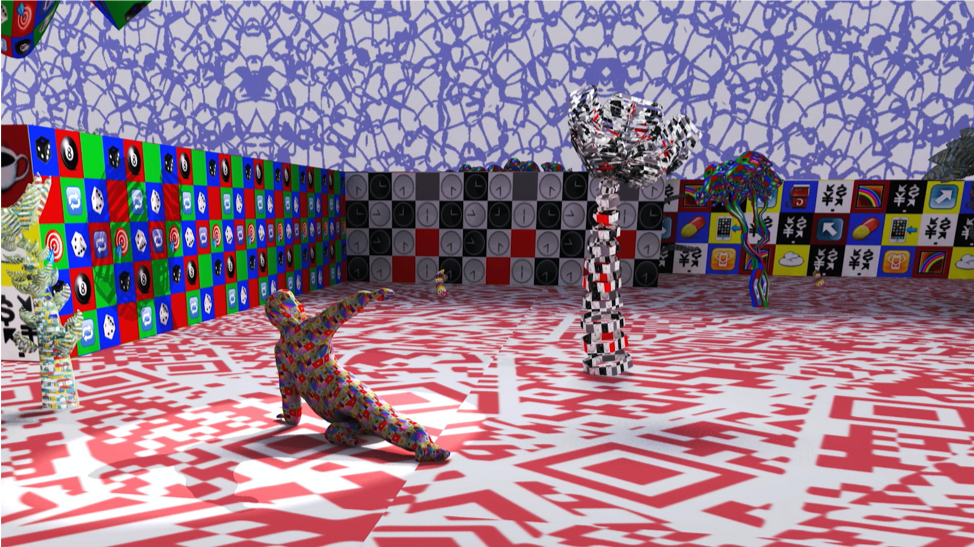

Claudia Hart, Alice Unchained: A Virtual Chamber for Chamber Music, 2018. Three-channel projection. Music Composition by Edmund Campion; Choreography and Captured Dancing by Kristina Isabelle; Wrestling Routine and Captured Performance by Isaias Valesquez; Log Drums by Loren Mach and Dan Kennedy; produced by The Center for New Music and Audio Technology, UC Berkeley; Editing: Meredith Leich; Motion Capture Technical Producer: Stéphane Dalbera; Motion Capture Director: Jeremy Meunier; Motion Capture Studio Courtesy Of: Game On, Montreal; Motion Capture Post Production Courtesy Of: Atopos, Paris, in partnership with the Bachelor in Real-Time-3D Program, HECTIC, Paris; Motion Capture Senior Animator: Benjamin Moity; Motion Capture Junior Animators: Christophe Bonnard, Lélanie Campet.

An early practitioner of 3-D animation and a pioneer in its incorporation into contemporary art, Claudia Hart’s work subverts notions of technological culture as a gendered masculine space. Hart’s Alice Unchained: A Virtual Chamber for Chamber Music (2018) uses 3-D animation software to create a virtual space that references nineteenth-century salons. Alice exists as a performance that unfolds in the physical and virtual realms. Live motion-captures of a professional wrestler and a dancer are composited together in real time. In doing so, the binaries of gender become fluid and combine to make a hybrid avatar whose choreography is unified by the artist and the computer. Hart’s avatar frees the body from prescriptive conventions of gender identification, using technology to reclaim power over these categories. Acting in tandem, Hart’s collaborator Edmund Campion composed the audio track with live drummers. The world in Alice unfolds simultaneously in the physical and virtual realms. Hart’s animation is captivating, but also overwhelming, partly because figure and environment alike are covered in a flashing pattern. Acting as an animated billboard or GIF, the material appears to consist of a pattern created from emoji icons. The floor of the fictional space is covered in contrasting squares resembling a QR code.

Loosely inspired by the liminal world of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland books, wherein the conventions of daily life are suspended, Hart’s piece destabilizes binaries of signification through the malleable language of digital media. The cyborg avatar rejects traditional markers of gender, instead becoming a fluid body that is freed from such constraints and able to perform a new version of the self within this virtual space. The emoji patterns, out of their usual context, read as simple colors and shapes. Hart acts as a cinematographer, director, and architect within the virtual world of Alice Unchained, using 3-D animation in order to queer the construction of bodies and space alike. When experiencing Hart’s creation through a VR headset, the viewer is directly immersed within the piece, navigating their own body (or lack thereof) through the same virtual world that the avatar inhabits.

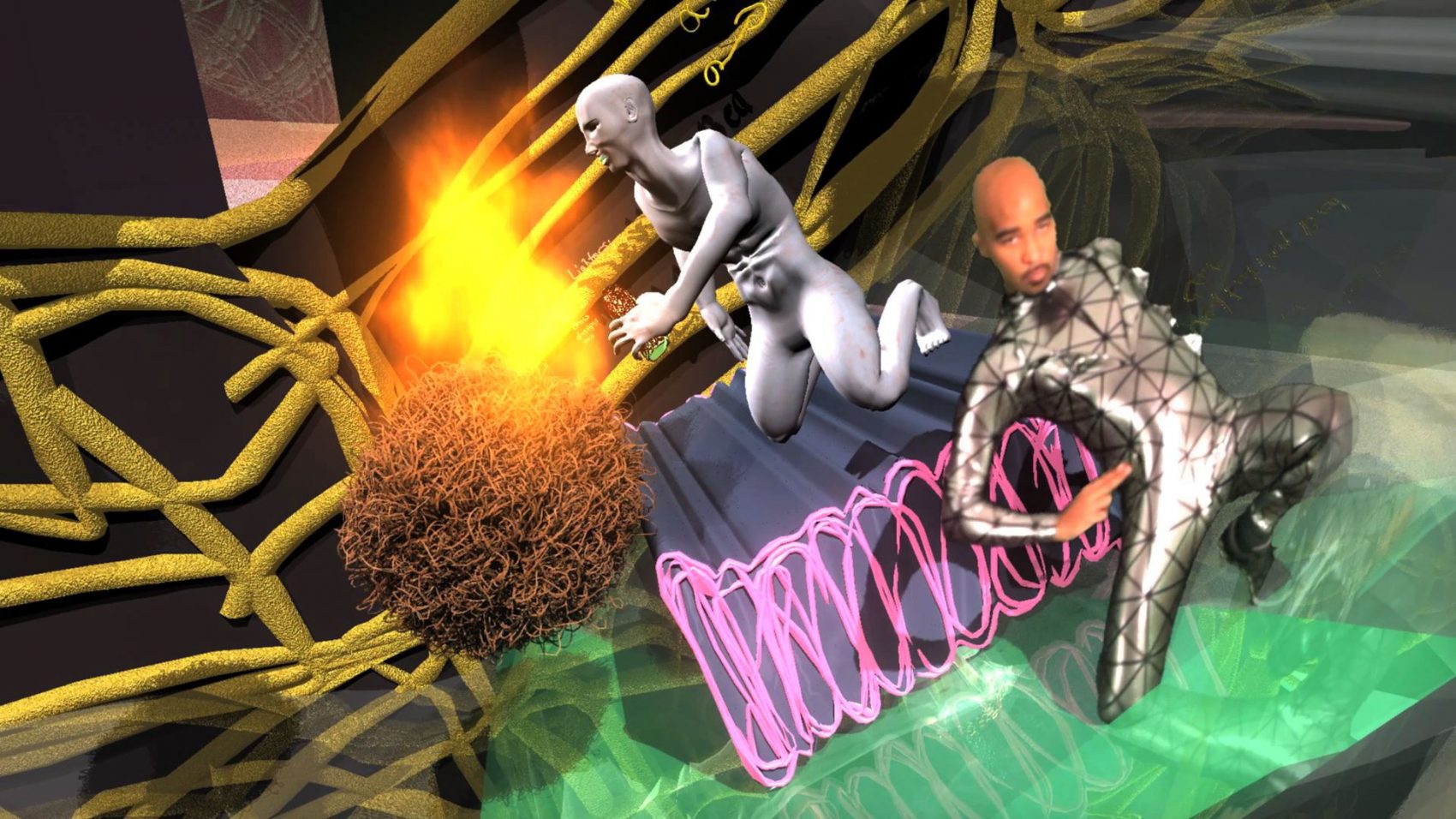

Jacolby Satterwhite, Vintage Paradise, 2019. Video still. Virtual reality video with sound. © Jacolby Satterwhite. Courtesy of the artist.

The very ethics of entering a dynamic work come into question with Jacolby Satterwhite’s Vintage Paradise, a 360-degree video in which viewers are treated to a repository of the artist’s personal images and objects, decorated with numerous sketches of proposed inventions by the artist’s late mother that have been extruded into 3-D. The driving force of the artist’s work is the creation of fantastical worlds that, similar to Hart’s Alice, queer notions of both space and the body. In many of Satterwhite’s earlier works, such as Reifying Desire 5 (2012), motion-capture 3-D animated compositions of the artist are seen performing a ritualistic, vogueing-style dance inspired by the queer ball scene from decades past. In Paradise, however, the artist’s body is absent. Instead, the only figures that are visible within the piece are photographs of family that function as static props. Satterwhite re-contextualizes the act of remembering as a visual and physical journey in a simulated interior space, inviting the viewer into this world as an observer. In this way, the artist divides the space into the observer (the viewer) and those being observed (the world created in Paradise). Our act of looking reminds us of the power to gaze at will, and what that implies. What does it mean to be a bystander and an onlooker in an intimate space—especially one so significant to the artist’s identity?

The ability to look around the artist’s fantastical worlds adds a new dimension to some of Satterwhite’s earlier works that present animated elements and figures in an ornate, virtual space. The artist’s background as a painter is evident. One can observe the parallels between the scene in Vintage Paradise with that of Diego Velázquez’s Las Meninas: Both imply the act of looking, artifice, and representation. Both artworks seek to situate the viewer within a specific viewing context—as royalty (Meninas), or as an interloper in a personal history (Paradise). Much as Hart uses cinematography in Alice Unchained, Satterwhite carefully orchestrates our experience as a series of spherical stills, determining the scene and perspective and controlling the degree to which the viewer is able to navigate through the piece. We are at once immersed in the scene and made aware of the limitations placed on our gaze by the artist—whose image is seen on a reflective surface (used as an HDRI), implying the presence of the artist in the constructedness of their Vintage Paradise.

Jacolby Satterwhite, Reifying Desire 5, 2012. Video still. 3-D animation and video with sound, 8:47 min. © Jacolby Satterwhite. Courtesy of the artist, Electronic Arts Intermix, New York, and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

In our culture of mediated images, the medium of 3-D animation is the message: everything we see is a construction. Using digital tools, Torn, Hart, and Satterwhite are able to challenge constructs pertaining to gender, the body, and subjectivity. They show how digital mediums, and 3-D animation in particular, might emancipate signification from conventional forms and contexts. The virtual worlds artists create provide space for a constant revisioning of the self. x

Melanie Nakaue is a Los Angeles-based artist and designer. She is currently Visiting Assistant Professor in Art at Scripps College.