There was once a prince whose father confined him to a palace that had every luxury and protected him from all suffering. One day, despite the king’s wishes, he snuck out into the countryside with a trusted advisor. Along the road, they encountered an old man, a sick man, and then a corpse. The prince, being wholly ignorant of suffering, exclaimed at each encounter, “What’s this?” Each time, his advisor assured him of the normalcy and inevitability of the affliction. After his adventure, the prince’s cloistered life became unbearable. He realized the sanctuary of the palace was an illusion and the suffering he had witnessed outside its walls was the truth. He renounced his title, cast off his princely robes, and left the palace to found the Outsider Art Fair, the only fair dedicated to showcasing self-taught art, art brut, and outsider art from around the world.

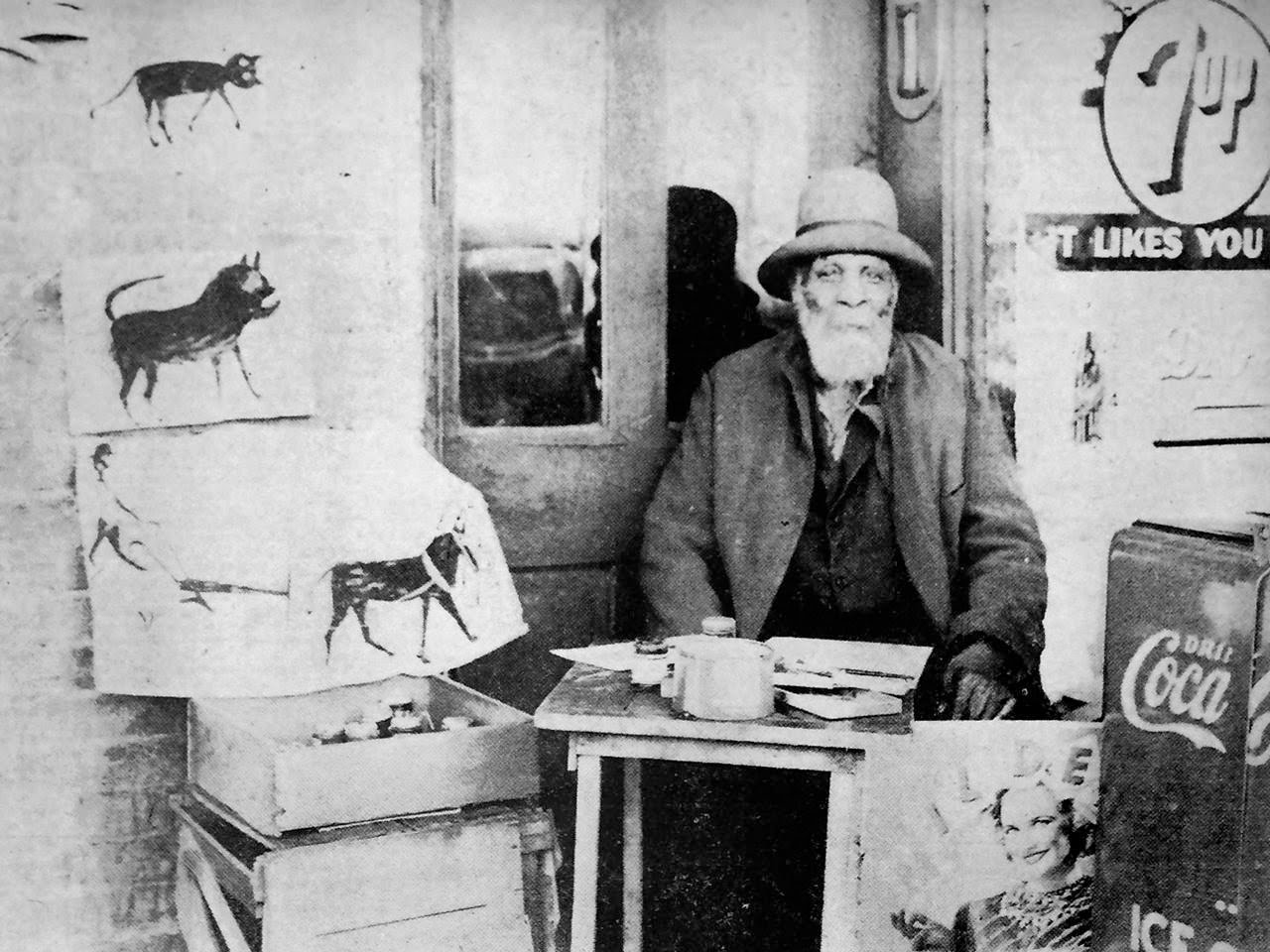

Bill Traylor pictured in the Montgomery Advertiser, March 31, 1940.

Just as the young Buddha gleaned while wandering the ancient Indian countryside, the interaction of suffering and desire defines us and our actions. The Outsider Art Fair (OAF) is no exception. It is a tour of human ambivalence, teeming with atrocities, eccentric outliers, cruel blows of fate, and giddying, unchained creativity. Oxymoronically, the Outsider Art Fair celebrates the interior, self-centered worldview of the isolated individual. Like the outsiders it showcases, this exhibition plays Cinderella to the stepsisters’ pageantry of the big tent art fairs which operate within the luxury goods industry. That privileged sphere emphasizes what the royal “they” do and consume, unencumbered by the ill effects displaced onto the teaming mass of “we.” Like populist politics—which affirms for this “we” that each and every one of them is entitled to a kingdom, its borders walled off by their own brutishness—the OAF is a mess, but it’s our mess, and we should have been paying more attention to its constituents before they came crashing in. Although rife with exploitation (Michael Stipe promoting his personal “outsider” brand) and poor taste (realistic depictions of faces presented as something about pareidolia which I would have alternately titled “Looking At Clouds, I See Cold Steam”), the OAF’s folksy populism has something really real at stake: an opportunity to inquire into the condition of others and react to that. Empathy, at an art fair.

Bill Traylor, Construction with Exciting Event, 1939-1942. Tempera and graphite on reverse of repurposed card poster, 11¾ x 11¾ in. Courtesy of Ricco/Maresca Gallery, New York.

Bill Traylor was born into slavery in the American south. Post-emancipation, he worked as a sharecropper, had multiple families with many children, and eventually found himself down and out on the streets of Montgomery, Alabama. At age 85 he began to reflect on his experience through a prolific painting and drawing practice in which the animals, people, and events from his life form a tumbling visual memoir that is both folksy and nightmarish. Traylor was able to achieve something rare for a person with his biography: he was “discovered” in his lifetime, exhibited within the establishment, and eventually anointed (in spirit, if not materially) into the canon of Outsider Artists. Traylor’s life and work are as enduring as the bigoted, authoritarian system that enslaved him.

Is it any more possible to truly own a drawing by Bill Traylor than it was to own him? When the Smithsonian posts that Traylor is regarded as “one of the most important artists of the 20th century,” does that make his experience as human property in the 19th any more palpable today? Or, is the feeling of empathy his work inspires a projection of the desire to share our own burdens? Much of the artwork at the OAF was made without access to the currencies of art-historical categorization, media attention, or the auspices of a major world religion. This is the folk, the “We the People,” exercising the equal opportunity to refer to one’s own experience. Traylor’s oeuvre is only understandable in that it represents the un-understandable subjectivity of his life to everyone from young white art patrons to his relatives, who were surprised to learn that grandpa was a notable artist.

One of the defining characteristics of the outsider genre is inscrutability. To be an outsider is to exist, at least in part, beyond empathy. Life outside the palace walls is familiar and alien to us all. It’s a lonely country.

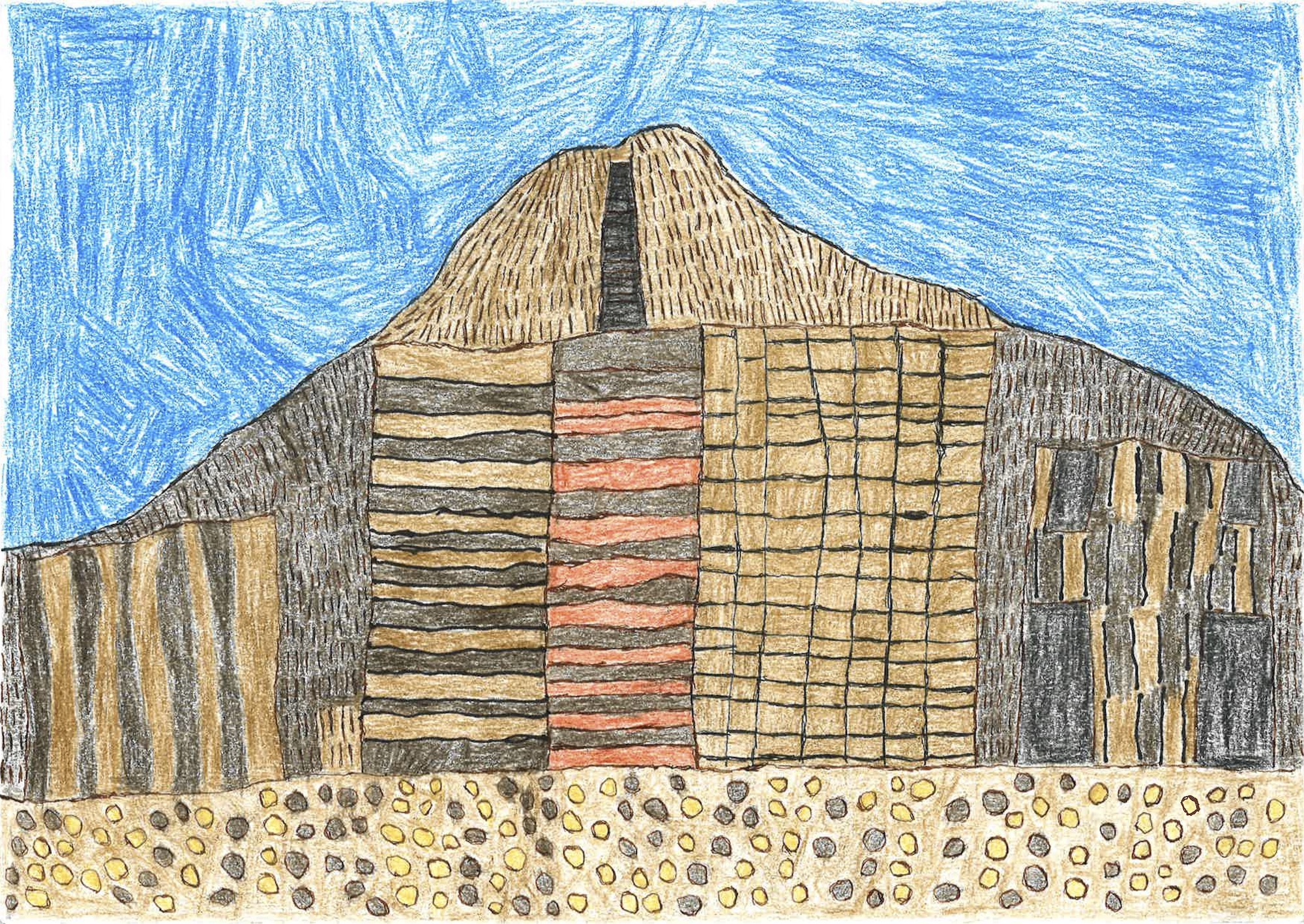

Paige Donovan, Mountain, 2021. Colored pencil and ink on paper, 9 x 12 in. Courtesy of the artist and the Center for Creative Works, Philadelphia.

Flipping through the flat files in the Center for Creative Works booth, a small drawing by Paige Donovan titled Mountain (2021) caught my eye. It depicts a yonic peak faced with gridded structures like agricultural parcels or a desert city rising in the foreground. Paige was booth-sitting alongside the Center’s staff. I asked if she had drawn any particular mountain.

“It’s brown,” she replied.

The Center for Creative Works is a Pennsylvania-based supported studio “with a goal of developing creative potential and cultural identity for people with intellectual disabilities.” Their program, like others of its ilk, promotes self-directed creative practice as a vocation, less like crafting or art therapy and more like a studio-based MFA program.

Paige’s blunt response was that of a confident artist. She has been working in the studio five days a week for over 15 years and seemed to be doing a brisk business at the fair. According to the Center’s website, she is also a Paralympian in backstroke. The comparison between the Outsider Art Fair and the Paralympics is awkward but illuminating. In the Paralympics, a field of athletes, each with different bodies and abilities, compete in the same event, redefining peak performance as plural. In comparison, the unqualified Olympics, where athletes—genetically hyper-abled to eke out competition over micro-fractional differences in their performance—can feel as petty as the most privileged and insular corners of the contemporary art world. The recent uptick in athletes’ consciousness raising around the regressive ethics of their sports’ handling of mental health, gender, race, and so on easily maps onto the dialogue around plurality in which the OAF trades. One gets the impression that the fair initially staked its identity as antagonistic to art establishment gatekeepers without realizing that, in the aftermath of its uprising, it would inherit the impossible duty of downstream accountability.

Although communication was difficult, Paige and I made typical art fair small talk. Donovan’s disability impacts her verbal expression and motor skills, bottlenecking her capacity as an artist. Uninvited exploration of an artist’s biography easily breeds toxic positivity and other essentializing diminishments which dislocate meaning from the artwork that the artist chose as its conveyance, undermining their authorship and agency. Paige is part of a long tradition where, as they say, the art speaks for itself. Mountain spoke and, from behind its edifice, seemed to say, “If art is self-evident, what of the artist?”

What is apparent from the booths assembled at the OAF is that outsider art exists in the eye of the beholder. When reading the artist’s biographies (and oh my do biographies abound), a pattern emerges—the artist’s experiences cluster in a certain bandwidth of the spectrum of life. Most of the artists here aren’t bohemian scions—they are from the ranks of the most vulnerable and least seen. This is art by individuals dealing with the conditions that define an experience of outsiderness: physical and mental disability, neurodiversity, censorship, shame, disenfranchisement, alienation, ostracism, fanaticism, obnoxiousness, mental illness, addiction, incarceration, poverty, slavery… All of these are states replete with hardship, readily apparent to others but not easily shared.

Alan Whitney. Color photograph, 4 x 6 in. unframed. Photo: Nick Kramer.

“What’s this?” I asked the art dealer. He began to reassure me of the normalcy of what I was seeing with snippets of the maker’s biography.

We were looking at a framed 1-hour photo print of a cluttered living room in which a young bare-assed woman lays prone across the lap of an old, pasty man. On the wall behind them, almost illegible but seemingly in the style of Norman Rockwell, is a poster of a dapper man and schoolgirl engaged in the same conduct. The man in the photograph, I am told, is Alan Whitney—purportedly a former editor at the New York Post or Daily News who had a thing for photographing his thing for spanking. The resulting archive of snapshots is now in the inventory of Brooklyn’s Winter Works on Paper. In the image, Alan seems caught off guard even though he is its author. For him, these images are presumably thrilling private fetish objects. For us, they are an ill-gotten window onto the messy interior world of another. Whitney’s photo reads as uncontrived, accidentally speaking volumes about the flashbulb anemia of his saggy arms against the blown-out creaminess of a butt in its prime. Alan’s life is not unempathetic; he traveled the road, grew old, sickened, and then died, leaving a stack of photos as his legacy. However, Whitney is an editor, not an artist, and his snapshots are ultimately as artless and alienating as the adjacent display of UFO photography.

Within its fold, the OAF includes several breeds of folk-erotica. These works, not the beatific suffering presented for virtuous-minded fairgoers, are some of the most persistent and darkly engaging on display. Ranging from Whitney’s porny recordkeeping to Berry Horton’s lusciously exaggerated drawings of women, much of it, once seen, can’t be unseen. This “work on paper” finds its way Outside via the maker’s transgression. There is an exciting sense of permission when someone lays their desires bare for you, and there is a thrilling power to observing their sex life without their knowledge. Although Whitney and the woman are presumably engaged in consensual play, consent remains a serious question in the production and subsequent upcycling of this erotic material—not to mention the other art on display. The erotica, Whitney’s included, presents as oddly quaint. If yesterday’s smut is today’s camp or kitsch, could this register of erotica ever have come to be in today’s world, where ubiquitous amateur pornography and a widening pool of taggable identities are gentrifying the fringes of our formerly-private lives?

Rioters at the Capitol Building in Washington, DC, January 6, 2021. Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License. Photo: Tyler Merbler.

To encounter disability or cruelty when venturing beyond the kingdom of privilege is to encounter the desire to know its truth without becoming its subject. However, the passports of suffering are not issued to those of us who only wish to visit a reality that is seemingly more authentic than our own. It is as easy to fall back on toxic positivity in an attempt to appreciate the experience of another as it is hard to embrace one whose acting-out affronts our own worldview. Both confrontations ignore the fact of the other’s suffering. Suffering is universal but not exchangeable. In booth after booth at the Outsider Art Fair, looking for a silver lining or self-affirmation is erasure, equivalent to looking away altogether from those who have traveled there on unfortunate papers.

Whether the trade is prim or rough, the Outsider Art Fair is an ideological riot. The label Outsider euphemizes a real cohort of people without access to that which is taken for granted on the other side of the palace wall. Viewed today, Donovan’s brown mountain, Traylor’s cryptic antebellum shorthand, and Whitney’s flash-lit fetish all fall on a continuum of folk expression which is traceable to the similarly inscrutable, and retrospectively obvious, action of storming the US Capitol. A membrane is pierced and, like a gas, chaotic anguish fills the neat void, seeking to be held. x

Nick Kramer is an artist, curator, and occasional writer based just outside Detroit. He co-founded the artists’ gallery AWHRHWAR in Los Angeles and became interested in the subject of Outsider Art while working at a supported studio for adults with disabilities even further outside Detroit.