The sunshine is a glorious birth;

But yet I know, where’er I go,

That there hath past away a glory from the earth.

–William Wordsworth, “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood”

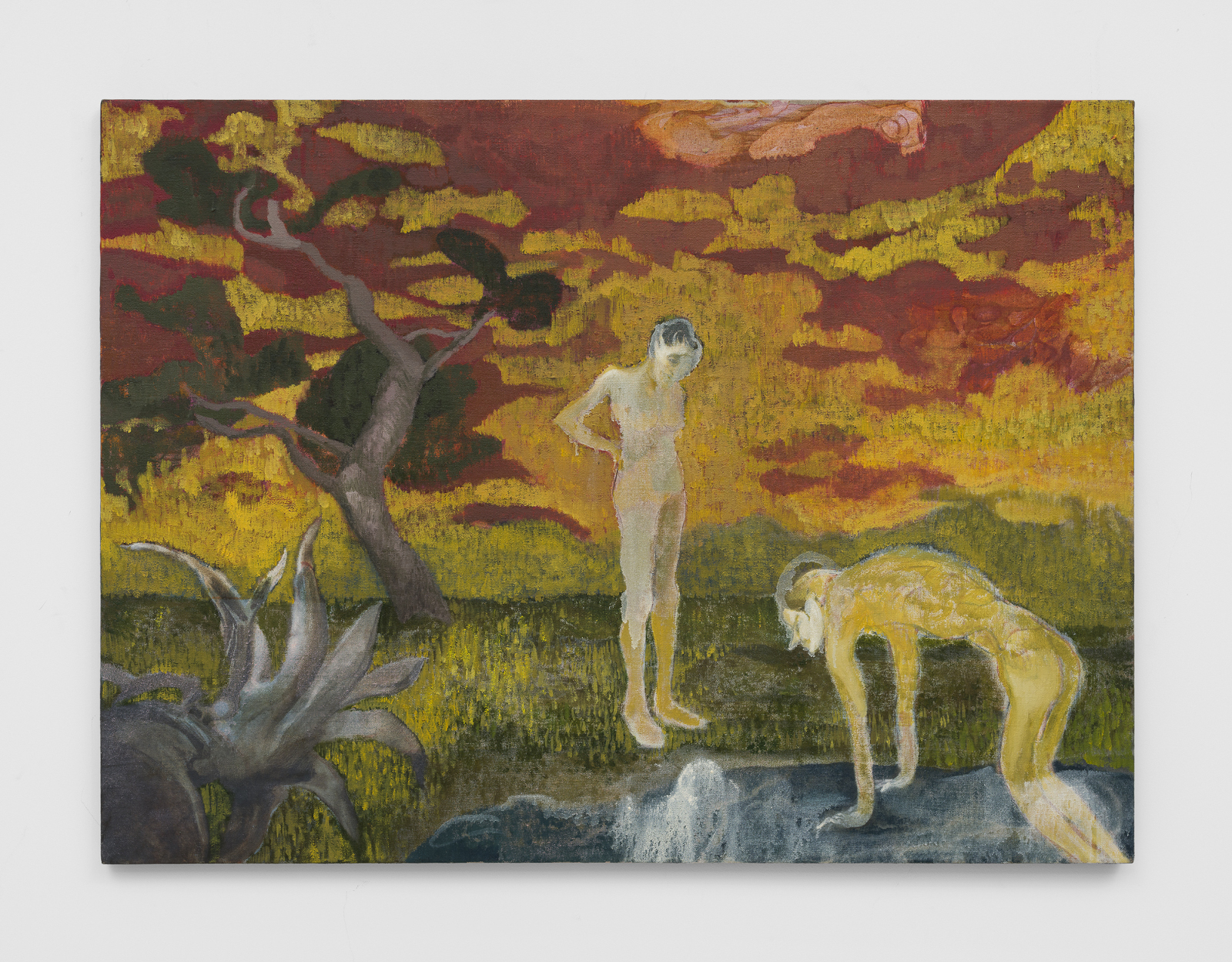

TARWUK, MRTISKLAAH_Behelit, 2020. Oil on canvas, 28 x 38 x 1 in. Courtesy of TARWUK and Matthew Brown, Los Angeles. Photo: Ed Mumford.

“Together these works display an affinity for feeling over logic,” writes curator and artist Lucy Bull in her press release for Emblazoned World, a group show at Bel Ami. “There’s no conceit behind this show exactly; these artists simply resonate with me.” Bull dismisses rational organization in favor of emotional subjectivity—a preference reflected not only in Bull’s own work but in much Los Angeles painting from 2021. Her sentiment sums up an emerging interest in Romantic painting, particularly in relation to the Romantic sublime: no less than Caspar David Friedrich preempted Bull’s statement in the early nineteenth century, writing, “The artist’s feeling is his law.”

The original Romantic movement staked out an alternative to structures of rationality, logic, and order in the wake of the Enlightenment. These painters and poets favored intense, awe-inspiring landscapes, an investment fueled by nature’s absence in growing, industrializing European and American cities. In 2021, three Los Angeles solo exhibitions—Bull’s Skunk Grove at David Kordansky; Sara Issakharian at Tanya Leighton; and TARWUK at Matthew Brown—took up the impulses of their Romantic forebears, reevaluating the emotional relationship between human beings and the environment.

If the Romanticist stance is turbulent, characterized by the fear and delight conjured by the boundlessness of nature, then this contemporary iteration is marked by its self-destructive orientation toward the sublime. Defined by Boileau’s 1674 translation of the writer known as Pseudo-Longinus, and elaborated by Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant, the Romantic sublime centers a liberal subject—the man in Friedrich’s emblematic Wanderer Above the Sea of Fog (1817), for example, or Wordsworth’s confident “I.” During the sublime encounter, the subject experiences the alienating potential for bodily danger and loss of control, and the consequent bliss of regaining self-sovereignty. Kant called the sublime sensation a “momentary checking of the vital powers.” Now, however, there’s little relief: an increasing vulnerability to the effects of environmental devastation forces us to recognize responsibility for our newfound peril. The ostensibly discrete pair—nature, the self—are no longer separate.

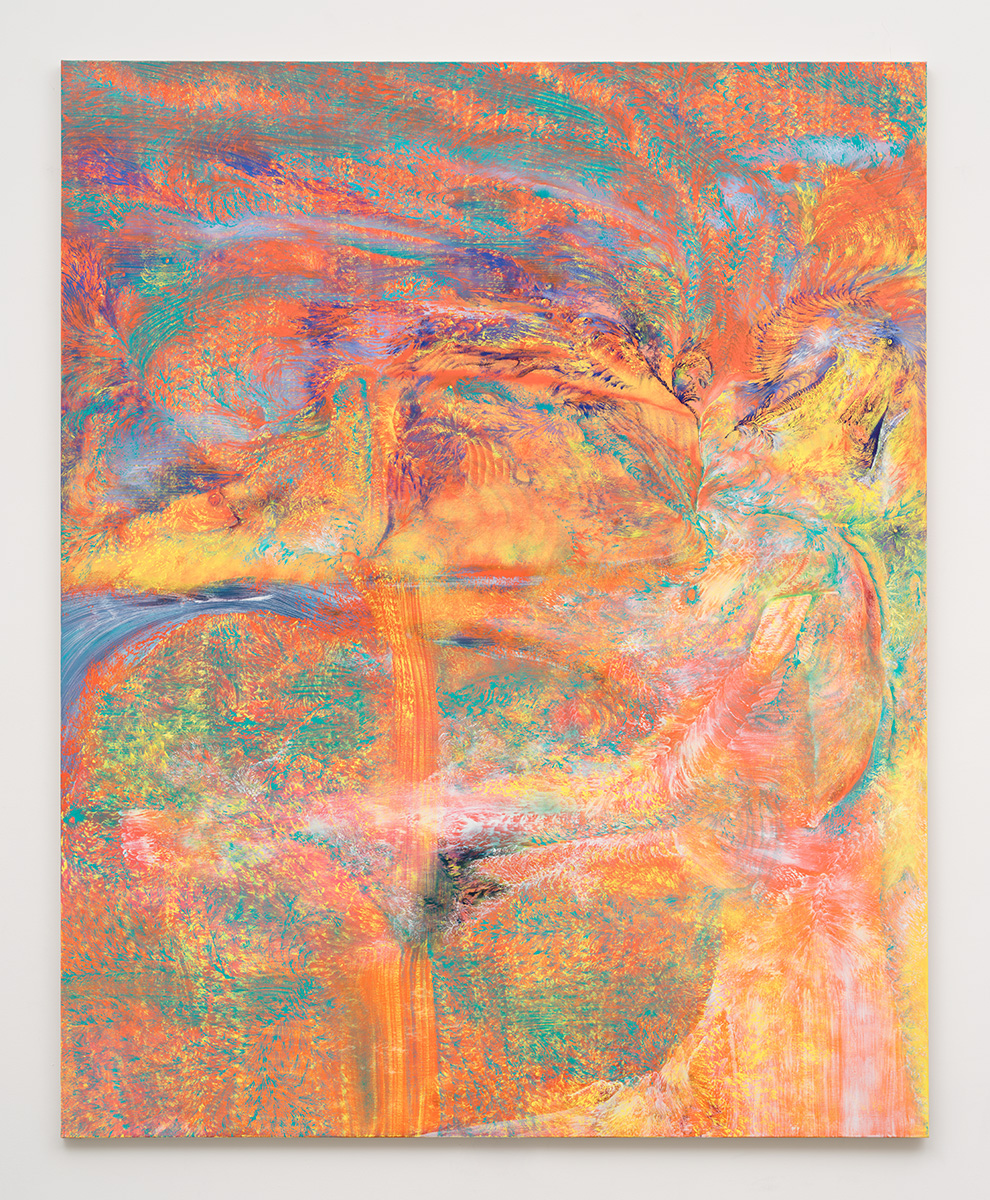

Lucy Bull, Veiled Threat, 2021. Oil on linen, 84 x 68 x 1 in. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff McLane.

In the contemporary Romantic sublime, emotive landscape paintings evoke the precarity of the human subject through dizzying perceptual experiences. At Skunk Grove, Bull displayed large-scale abstract paintings that conjure the whirling skies of J.M.W. Turner or Théodore Géricault. Kordansky’s press release places Bull’s inspiration in “the many shadings of the romantic sublime.” But where her Romantic influences depicted distinct figures and scenes, Bull evades realism, opting for the abstract feeling prompted by an experience with nature. The Romantic representation of literal bodies or natural scenes is superseded by an attempt to express the disturbed senses of the viewer herself. In Veiled Threat (2021), a tumultuous seascape in bright yellow and turquoise, the horizon line that stretches across the canvas intersects swirling patterns of clouds, water, and sun. This is a landscape under vertigo: it’s impossible to tell up from down, sea from sky. Even in Turner’s abstracted Snow Storm – Steam Boat off a Harbour’s Mouth (1842), the solid shape of a ship stands out against the tempest, signaling both the stable subjectivity of the painter’s eye and the resolute strength of man-made creation. Bull’s paintings offer no such assurances: her primary subject is the sublime event itself, a Tilt-a-Whirl of sensory experience.

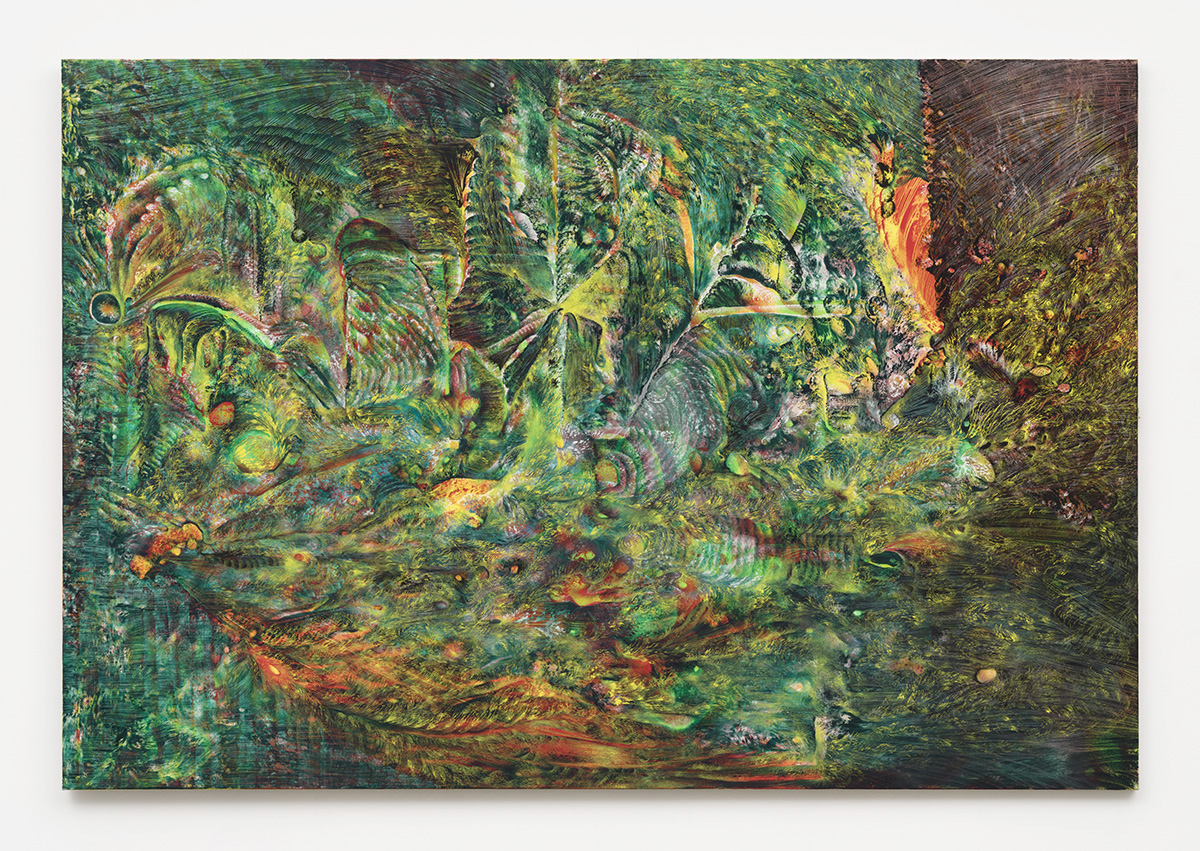

Sara Issakharian, Remembered Landscape, 2021. Acrylic, pastel, charcoal, and colored pencil on canvas, 76 x 132 in. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Leighton, Berlin and Los Angeles. Photo: Dan Finlayson.

Sara Issakharian’s paintings, like Bull’s, are aesthetically appealing: they are enormous, bright, balanced compositions that evoke the natural world. Both artists’ scenes delight while they disturb, suggesting the contrasting emotions of the sublime. In Remembered Landscape (2021), Issakharian takes up a Romantic theme, nostalgia for childhood, while denying access to the actual memory. The landscape itself is painted over in a thick fog of ivory paint; hints of blue and red emerge at the edges, suggesting the crystalline “remembered landscape” underneath. In William Wordsworth’s 1804 “Ode: Intimations of Immortality from Recollections of Early Childhood,” the poet laments the loss of an innocent idea of nature, freighted by his adult experience of early urban modernity. But while Wordsworth’s ode presents a singular, human speaker, the figures in Issakharian’s landscape are monstrous and absurd: a half-man half-horse beast in the upper corner is the lone being in the frame. Issakharian’s formal choices foreclose the implied Romantic narrative, her representations of humans and landscapes left fragmentary and incomplete.

TARWUK, MRTISKLAAAH_Die_Erinnerung, 2020. Oil on canvas, 54 x 90 x 1½ in. Courtesy of TARWUK and Matthew Brown, Los Angeles. Photo: Ed Mumford.

In an interview with BLOAT MAGAZINE, Croatian duo TARWUK also cites inspiration from childhood, specifically from their experiences of the Croatian War of Independence. MRTISKLAAAH_Die_Erinnerung (2020)—die Erinnerung means “the memory”—shows a crowd of people cowering in fear before a menacing field of boulders and spires. As in Bull’s work, TARWUK conjure the terror of the sublime through abstraction: the background’s palette is that of a stormy sea, but one comprised of geometric, bubbling shapes reminiscent of dark caverns and ocean floors. The group pictured in the foreground is mostly obscured, their faces turned away from the viewer, arms raised in fear. Just one figure stands out, its mouth opened to reveal sharpened teeth. Half of the figure’s face merges with the swirling blue and yellow circles in the background. Here, the Romantic precedent is abandoned: TARWUK’s landscape tips into the unreal and does not present a strictly human subject. The painted figures are grotesque and soluble, melting into the natural scene. There is no stable guide to lead the viewer through the potentially destructive sublime, no solace of subjecthood.

Lucy Bull, Stinger, 2021. Oil on linen, 54 x 79 x 1 in. Courtesy of David Kordansky Gallery, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff McLane.

From Issakharian’s foreclosed nostalgia to Bull’s internal observer, coherent identification between the viewer and the view is no longer the goal. Perhaps in response to the social turmoil of the 2020s so far, these volatile, sensory scenes focus on individual perceptual experience. Subjective instability takes the place of overt political statements, sidestepping the often simplistic responses to COVID or climate change writ large, and presenting the viewer with a disoriented—and maybe realistic—powerlessness. Lingering in Friedrich and Turner’s heavy footsteps, these three painters capture the changing, violent character of a new Romantic sublime. At least, as Bull would say, that’s how it feels. x

Claudia Ross’s writing has appeared in The Baffler, Hobart Pulp, X-TRA, GARAGE, The Los Angeles Review of Books, and others. She lives in California.