What is debt? What is credit? What do we owe one another, and what burdens do we share? For the Dispatches column, Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi takes on the social and bodily propositions of Emily Barker’s exhibition Illusions of Care at Carlye Packer HQ in Los Angeles, on view February 4–March 25, 2023.

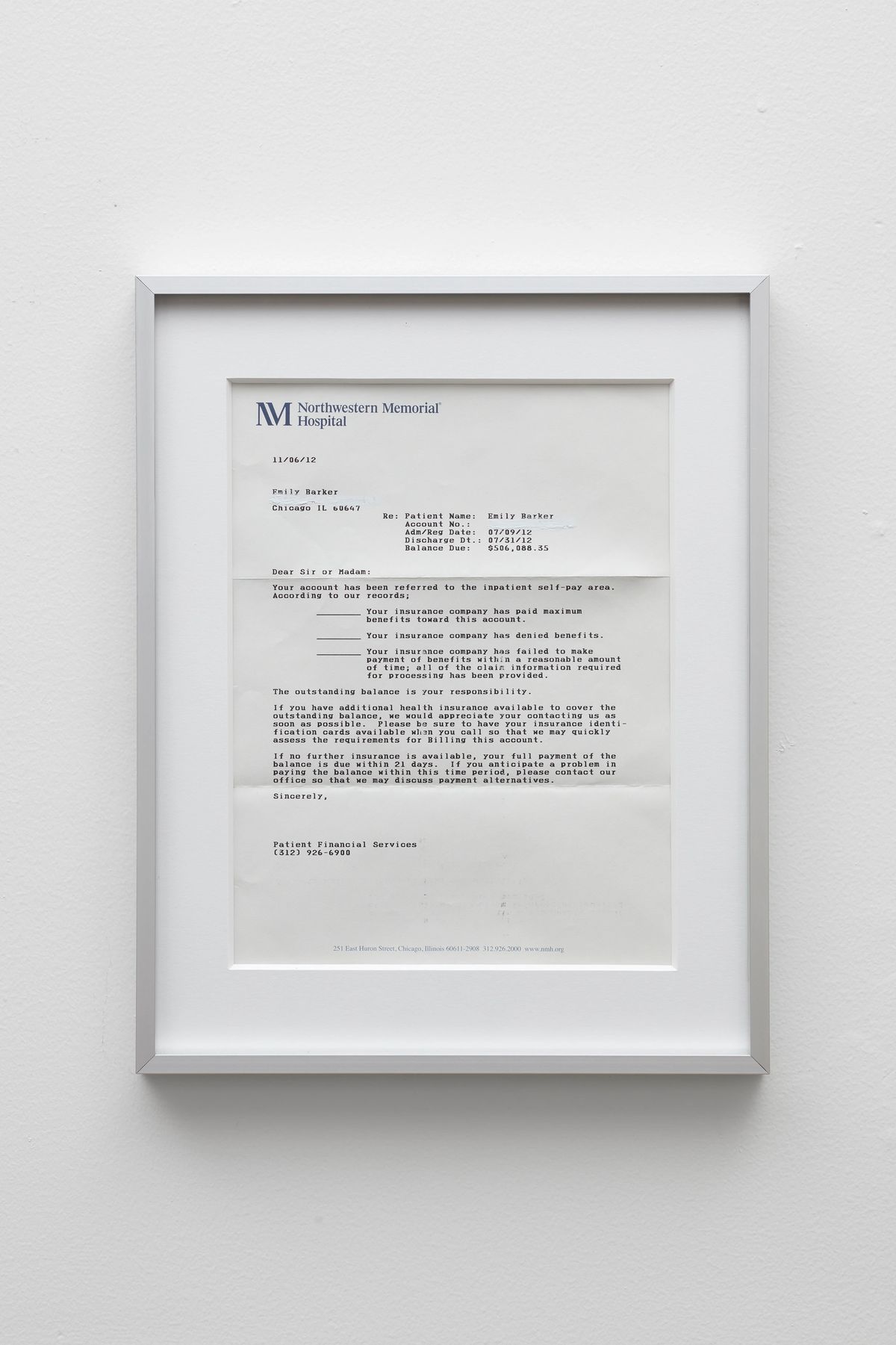

Emily Barker, Land of the Free, 2012/2021. Framed medical bill, 11 x 14 in. Photo: Evan Walsh.

$506,088.35.

This is the debt Emily Barker owed in November 2012. I know this thanks to Land of the Free (2012/2021), an austere, 14 by 11 inch white-framed artwork, hanging by itself on the wall. The contents: a medical bill from Northwestern Memorial Hospital. There are bigger, more striking works in the room at Carlye Packer HQ, but there’s something about this lonesome placement of Land of the Free that gets at how debt isolates, pushing those on the margins of society further afield. It shouldn’t be like this. Northwestern Memorial received an endowment in 1914 from philanthropist James P. Deering to support free care. Now, this hospital is an illusion of its past promises, burying people like Barker in debt.

I’d like to think that, per Marx, the solitary “form of appearance” of this medical bill speaks to the subjectivity of debt. For many, myself included, the burden of debt is not just economic, but emotional, with each bill potentially diminishing one’s labor power. If you get too overwhelmed, work seems impossible. Alas, there’s nothing “fictitious” about the indignity that debt causes.

Barker holds no illusions about this. Yet, borrowing from cultural theorist Miranda Joseph, I would argue that Barker resists the idea of debt as “a story of the destruction of community by quantification.” We might see Barker as isolated, saddled with all these arrears, but the vulnerability of Land of the Free suggests there’s plenitude in debt, a window through which community could rally around the artist.

This rallying is really an elaboration. Barker’s debt is no different from the debt incurred by countless people navigating the medical-industrial complex. A possible singularity: Barker’s debt is fugitive. It runs up the tab of bare life, which is to say their debt will only accumulate. (Barker’s Death by 7865 Paper Cuts, 2019, consists of a stack of 7,865 pages detailing a life-care plan and medical bills from 2012–2015.) What if Land of the Free is paid for? I mean the work itself, not the debt—although Land of the Free is priced at the amount on the bill. (Carlye Packer confirms that the gallery has no consignment attached to this work; all funds would go directly to Barker’s debt.) Buying their debt could be an act of restorative justice. But would it, though? Does writing off the particular debt attached to Land of the Free alter our regard for Barker or the financial system of capitalism? Do we trust one more than the other? It’s hard to say.

As Stefano Harney and Fred Moten write, once you see debt, you see it everywhere—which is to say, credit is just debt dangled differently before us. No one wants debt. But we lust after credit. This discrepancy registers as the “phantom-like objectivity” Marx identified in capitalism—a haunting that renders debt and credit, in the eyes of Joseph, “as immediately identical.” For this reason, standing face-to-face with Land of the Free seems sinister. It haunts me in an uncanny way. The debt feels familiar—I’ve been here—and unfamiliar—I’m not there yet. I stress the yet as an acknowledgement of the façade of individualism celebrated in the refrain, “land of the free.” We all aren’t free. And the sooner we dispense with this myth, we may finally reckon with the boundless ghost of debt, echoed in Barker’s refrain that “being able-bodied is a temporary privilege.”

FICO credit scores stratify us into tidy categories delineating how well we can deal with credit/debt. I get the feeling Barker is concerned with values that are less orderly, which sociologist Avery Gordon argues would “be less damaging.” Were we to inflict less damage on people, then we might take the tack of cultural theorist Raymond Williams and invest in “values as they are actively lived and felt.” To get us making this investment, Williams put this thought out there: what if we shared—“dispersed and generalized”—the affective spoils of shame and fear when it came to debt? Parts of this charge echo Williams’s colleague Stuart Hall’s call for “nonreductionist ways of thinking” on concepts crudely limited to “idealistic exchange[s] of ‘good’ or ‘bad’ meanings.” Debt/credit can easily fall into trite binaries. How might we cohere this expansive and embodied thinking around debt/credit to the spectrum of health and bodily privilege so that we might glimpse the many sides of Land of the Free?

This elaboration both teases and threatens the possibility of credit to Barker, for they are a bad debt(or)—this medical bill hasn’t been paid. If it were paid, though, would creditors pursue Barker for more debt? No need to wonder. This vast, never-ending debt is intrinsically bound up in Barker being a physically divergent artist using a wheelchair. Barker was injured at the age of 19, which meant they hadn’t paid taxes on any earnings to qualify for Social Security Disability Insurance. That leaves them with Supplemental Security Income (SSI). Eligibility for this government support mandates a person with a disability must earn no more than $1,913 a month and must not possess anything worth more than $2,000 “that could be converted to cash and used for food or shelter.” The SSI payment maxes out at $914. If you work or engage in “substantial gainful activity,” that impinges on your SSI amount. Some states supplement people with a disability and living somewhat independently; California offers $1,133.73. If you do the math, it’s worth asking what actively living and feeling looks like for a disabled artist in a metropolis. Put another way, a W.A.G.E.-certified honorarium for a solo exhibition at any major Los Angeles institution would compromise Barker’s eligibility for government aid.

I’m looking at the framed bill, Land of the Free, wondering if anyone could pay for this “work” without jeopardizing Barker’s disability income. Technically, yes. There’s a proviso in the SSI program that payment of health insurance premiums by others does not constitute income. But the bureaucratic paradox of SSI policy still inures Barker and other disabled people to what Harney and Moten call a “reign of precarity,” or, put bluntly, a lifetime of debt. Make too much, you’re docked or denied SSI. Make too little, you’re offered a paltry sum, an insecure living. While Land of the Free is a radical proposition, it’s on us, fellow able-bodied citizens, to advocate against and rewrite the draconian policies around SSI. Or, embracing Denise Ferreira da Silva’s writing, this debt is unpayable in that Barker “owns (ethically) a debt, which is not (economically) [theirs] to pay.”

Emily Barker, Illusions of Care, 2020–2023. Thermoformed PETG plastic, rivets, 126 ¼ x 83 x 126 ¼ in. Installation view, Illusions of Care, February 4–March 25, 2023, Carlye Packer HQ, Los Angeles. Photo: Evan Walsh.

I find myself extrapolating this ethical disjuncture onto Barker’s marquee sculpture Illusions of Care (2020-23). At Carlye Packer, it was easy to miss Land of the Free perched on a back wall because of the towering, Renaissance-inspired columns and arches in Illusions of Care. One might expect a colonnade, but Illusions of Care resembles a strange loop, a stoa with a passageway leading nowhere. Think M.C. Escher’s print Relativity (1953), with Barker pushing the question of spatial logic into a formal language riddled with confusion. The paradoxical form of Illusions of Care exposes the crafting of inept legislation when government advocates for a just material infrastructure, what we might judge as the vainglory of tradition. When President George H.W. Bush signed the Americans with Disabilities Act on July 26, 1990, in a ceremony on the White House’s South Lawn, off in the distance behind Bush was the Jefferson Memorial, a neoclassical monument held up by marble columns in a Doric order. Jefferson was proximal to disability; he struggled with dyslexia and personal letters suggest that his siblings also exhibited learning disabilities. Yet despite this longue durée of disability in America, legislation and public policy have narrowly conceived of accessible design.

I glimpse this derelict care in Pressure Sores (2017), a line of four black ROHO pressure sore wheelchair cushions pinned to the wall. They all belong to Barker. Each cushion reveals varying degrees of wear and tear. Although specially designed to offer much needed relief to those who must sit for long periods, the dilapidated state of Barker’s cushions suggests that these devices deliver less than they promise, in part because of the realities of their cost. Is this care or cruelty? On evidence, I’d say the latter. Barker must contort their body, life, and narrative for SSI benefits that grossly fail to cover their assistive device costs of $5,000, wheelchair costs of $26,000, and their ongoing pain treatment of $30,000. On the other side of the leger, the roughly $2,000 from SSI doesn’t consider the actively lived and felt realities of disabled people like Barker.

“People look at the world,” Barker states in a 2021 interview, “and they just think that everything—the way that everything is built, the way that all the systems exist—must be the best way, and that if you just follow the rules, you will be successful.” The rules are clearly flawed. Barker works with these flaws in their exhibition, putting forth the question: what would porticos, sidewalks, assistive devices, and healthcare systems look like if we actually cared for disabled people? Answering this begins by acknowledging that everything from SSI eligibility to infrastructure are a disservice—an illusion that violates the standard of care presumably cardinal to humanism. Indeed, humanism is questionable, in large part, because the above “standards,” according to disability ethnologist Cassandra Hartblay, “make everyone responsible at the same time that no one person is responsible for an end result.” Hartblay—and, by extension, Barker—would agree that we must understand “culpability for inaccess [… through] diffuse responsibility.” Until then, nothing about our thinking on debt, disability, or care will shift towards what feminist theorist Donna Haraway calls a “situated knowledge” where accountability gets vested within “communities.”

I’ve said a lot about what I know and don’t know thanks to Barker. Haraway might say what I’ve articulated resembles something of a “view from above, from nowhere, from simplicity.” This vantage point removes itself from community, locating itself beyond—rather than within—limits. By contrast, what Haraway would call a “view from a body”—my body—would suggest I locate myself within these “contradictory” standards of care. Barker was injured at 19. At 37, my body knows that it’s aging. I can’t run as many miles or bend over as easily. My medical bills are nowhere near as onerous as Land of the Free. Well, not yet. In the stark words of disability scholar Michael Bérubé: “the fact . . . many of us will become disabled if we live long enough is perhaps the fundamental aspect of human embodiment.” If we get behind this axiom, as a society, what do our visions of care look like? Nothing, I hope, like Land of the Free. x

Ikechúkwú Onyewuenyi is a curator and writer based in Los Angeles. He’s also on the editorial board of X-TRA.