The Dash column explores art and its social contexts. The dash separates and the dash joins, it pauses and it moves along. The dash is where the viewer comes to terms with what they’ve seen. Here, Mark Pieterson explores the role of territory, mapping, and utopia in Stanley Brouwn’s opaque poetics of belonging.

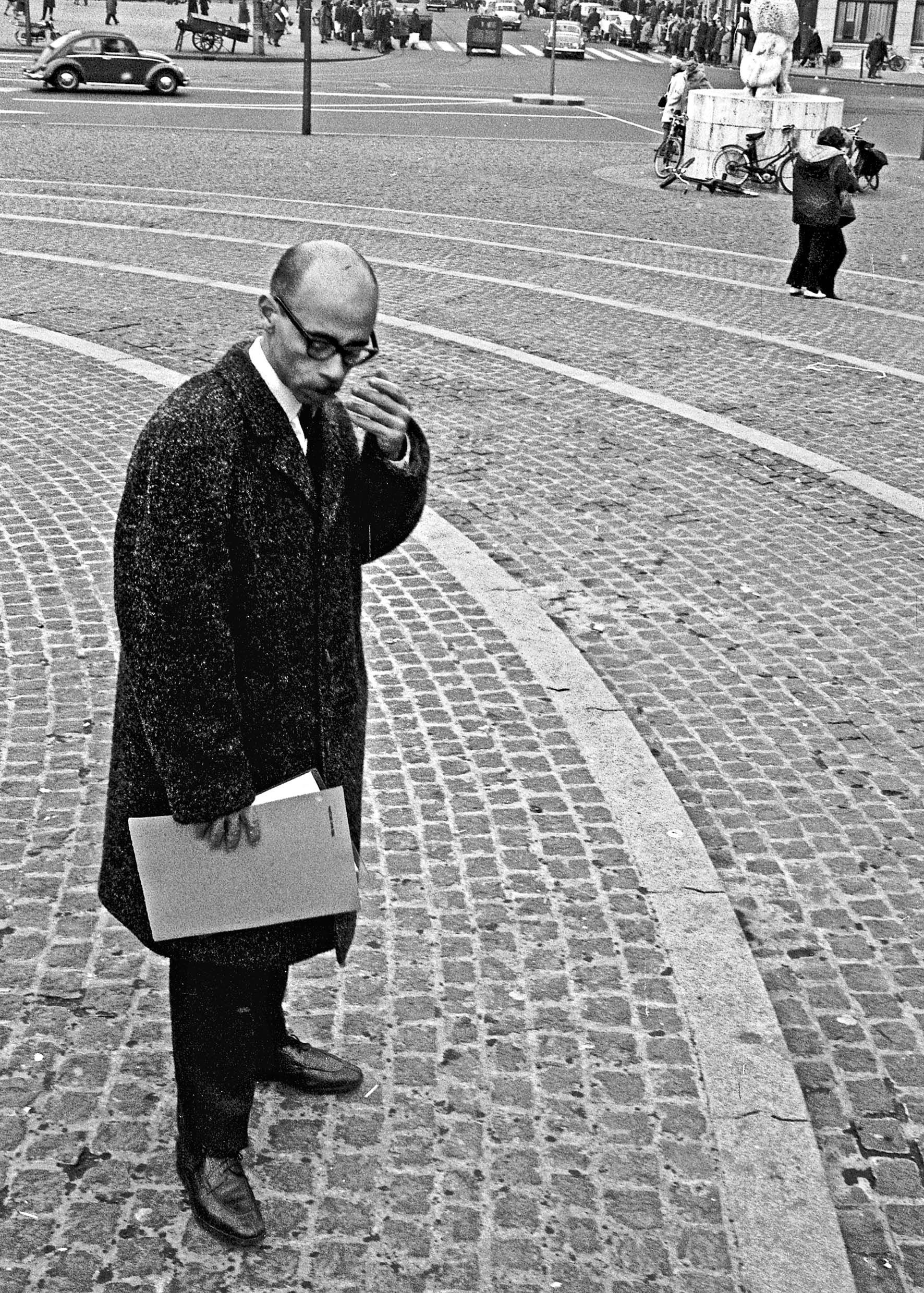

Stanley Brouwn, This Way Brouwn, 1964. Performance documentation. © Igno Cuypers. Courtesy of Igno Cuypers.

In 1960, the Dutch-Suriname artist Stanley Brouwn began a series of conceptual works titled “This Way Brouwn.” Wandering through the streets of Amsterdam, the artist asked passersby to provide directions to various locations, which they drew with black ink on paper stamped with the titular phrase. These intimate relational poetics became a staple of Brouwn’s practice, in contrast to the privacy and strict control of biography that he commanded over the span of his career: Brouwn, who died in 2017, rarely showed up to his own openings, gave few interviews and public statements, and often refused to provide images for exhibition catalogs. The artist’s methodical mix of psychogeography and absence of representation provides a useful lens for mapping opacity, as theorized by Martinique-born poet and scholar Édouard Glissant in his 1990 book Poetics of Relation. By adopting a poetics of refusal, and allowing memory, gestures, and a participatory ethic to map and produce bodies through lived experiences, Brouwn leaves us with a set of propositions for transcending the boundaries of the corporeal.

Brouwn’s early works consisted of transparent polythene bags filled with refuse and hung from the ceiling. Although he later destroyed many of these sculptures, favoring writing and cartographical mark-making to articulate thought and process, the tension between transparency and opacity, presence and withdrawal remained a constant in much of Brouwn’s output. Glissant distinguishes between transparency and opacity as a way to provide critical insight into the legitimizing power of identifiable difference, theorizing a social relation centered on undoing its hegemonic roots. Transparency, for Glissant, is a driving imperative in the cultural imaginary that seeks to understand and make the “Other” legible through categorization. Opacity, however, opens up the field of representation by centering unknowability and incompleteness as expressions of freedom. Opacity constitutes an in-between space of becoming that adds to the texture of fabrics that make up the “exultant divergence of humanities.” Glissant writes that opacity pushes “freedom to its ‘logical consequences’” by confirming freedom in an exploration of difference and excess.

Stanley Brouwn, This Way Brouwn, 1964. Performance documentation. © Igno Cuypers. Courtesy of Igno Cuypers.

This idea resonates with Brouwn’s 1964 manifesto written for the Institute of Contemporary Arts Bulletin in which the artist proposes an abstract future in 4000 AD “when science and art are entirely melted together to something new.” There, the body dissolves in favor of a “world of only colour, light, space, time, sounds and movement.” Why 4000 AD? Perhaps this is a measure of the length of time needed for the violence of colonialism to retreat from collective imagination, so as to realize an alternative to the discrete, subjected subject. Brouwn’s resistance to legibility—his pataphysics, even—complicates his relationship to thriving, contemporaneous schools of thought that explicitly centered filiation as a means of social and political affirmation, like the francophone Négritude movement popularized by Martinican poet Aimé Césaire and others. Whereas a thematic conception of diasporic Blackness energized this movement’s resistance to white hegemony, Brouwn and Glissant look beyond such politics of visibility and belonging, and the certainties they offer. In Brouwnhairs (1964), a 76-page book of single strands of the artist’s hair fixed to otherwise blank pages, the artist called into question the purported transparency of images and its relationship in the production of social bodies. Hair, an easily accessible forensic marker of identity, is used here less as a way to place one’s social location, but more as a recontextualized form of portraiture that goes beyond optics. Making the body multiple to itself despite (even through) corporeal absence, the publication challenges us to consider the boundaries of identity as they relate to techniques of difference and racialization.

Illegibility here produces indeterminate social texts across multiple landscapes and renders the material and ontological realities of erasure palpable. Brouwn achieved this by treating the world as he found it, which, in turn, allowed him to disrupt the calculus of cultural production. The acts of asking for directions and consenting to give them on the part of Brouwn and his participants, respectively, brush past the central conceit of Brouwn’s methodology, which casts him relationally as “stranger” and distinctly “Other.” Instead, what is highlighted and embodied in the resulting unskilled ink representations of memory and place is equivalent to what Glissant calls the “repercussions of cultures” formed by the collision of subjectivities in public, which opens up “lines of force [that] … vanish instantly.” With nothing more than a “THIS WAY BROUWN” stamp, we are essentially left with opportunities to view each Brouwn map as a condition of futurity—at once a place and a non-place, an in-between realm under constant construction. It is this alterity, assembled through social relations, which Glissant and Brouwn propose enables, in the words of the artist, “people [to] discover the streets they use every day.”

Stanley Brouwn, This Way Brouwn, 1964. Performance documentation. © Igno Cuypers. Courtesy of Igno Cuypers.

In Brouwn’s conceptualist acts of dematerialization and refusal, we see a further disconnect from postcolonial and abolitionist strategies that prioritize national affinity in their liberatory praxis, like the Back to Africa movement created by Jamaican revolutionary Marcus Garvey. Even as it resists domination, this solidarity approach presupposes an inscription of the absolutism of territory onto the body. H. Adlai Murdoch writes in “Glissant’s Opacité and the De-Nationalization of Identity” that “the erasure of the history, property, traditions, and practices of the colonized by inscribing them as intrinsically deprived, benighted, and inferior” characterizes the dialectic of the colonization process. A “return back to Africa” is seen as a way to grasp displaced kinships, but such thought has the unfortunate quality of marginalizing and homogenizing the terrain of difference on the continent of Africa in the diasporic imaginary.

Brouwn instead pushed the politics of withdrawal to its radical conclusion through artistic gestures that mimicked the violence of territorial dispossession, but in its performative absurdity called into question the systemic power relations of (neo)colonialism. In declaring all shoe stores in Amsterdam an exhibition in 1960—the same year he began “This Way Brouwn”—and, to a larger extent, in “collecting” a square yard of land in various cities, which eventually comprised the project Mother Earth, Brouwn appropriated the logic of conquest to locate the legitimizing power and extrajudicial overlaps of territorial sovereignty. These dramatics animated and politicized the historical materialism of ownership and the built environment rooted in privilege, injustice, and dispossession. For Brouwn, simply owning property in the abstract was likely never the end goal. Instead, the success of his performative trespass in Mother Earth and the shoe store “exhibition” required looking critically at the coupling of power and space, while conceptually dematerializing state borders suggested the need for alternative, porous metrics for belonging.

Stanley Brouwn, This Way Brouwn, 1964. Performance documentation. © Igno Cuypers. Courtesy of Igno Cuypers.

“We must clamor for the right to opacity for everyone,” Glissant proclaims. This assertion begs the question: What distinguishes the right to opacity from conventional human rights? Human rights as a concept presupposes that “‘human’ is a universal category accepted by all and that, as such, the concept does justice to everyone,” argues scholar Walter D. Mignolo in “Who Speaks for the “Human” in Human Rights?” But because the boundaries of humanity and citizenship are articulated through the lexicon of security and control that legitimize the maintenance of territorial borders, rights are conferred onto certain bodies under strict assessment of threat to the monopoly of power. This is what enables otherwise liberal democracies to “monitor closely or stop people who move excessively beyond the sanctioned schemas of mobility,” as Nabil Echchaibi writes. By insisting on indeterminism over universal truths, opacity opens a space where people are not sorted into the human and the inhuman, but where humanity is not a category at all. In Brouwn’s world of “color, light, space, time”—relation, in a word—borders have a different context altogether, not as sites for the management of risk, but as lines of transformation. x

Mark Pieterson is a writer, curator, and artist based in Los Angeles.