For the Re:Research column, poet and artist manuel arturo abreu explores how the sculptural practices of Aria Dean, Rindon Johnson, and Brandon Ndife cast off burdensome Western binaries—not least abstraction/representation—through Dean’s philosophy of the Black generic.

Rindon Johnson, I talk a blue streak or I’m silent. Fuck they free. Such a shame to see something that gives such pleasure sulking in a corner faulty. You have reason to celebrate? You are a bad dog? To desire to make an acquaintance, or a swan dipping their head in the water for food or water passing wind or the color produces the structure but the shape is all I want to cling to, 2019. Rawhide, paracord, dimensions variable. Installation view, Rindon Johnson and Lou Lou Sainsbury, you are telling my story. They tell and eat and kiss and play us, Yaby, Madrid, December 13–29, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Yaby.

In the face of the overdetermined European signifier of Blackness as void, negation, etc.—given that anti-Blackness renders Black people as ever-available, hypervisible raw material (“flesh,” as Hortense Spillers writes)—how can Black artists reintroduce a sense of mystery into art? What kind of sculptural practices in particular might resonate with Saidiya Hartman’s call to cease the circulation of trauma porn? Drawing on Aria Dean’s philosophy of the Black generic as a way of refusing the burden of Western binaries of abstraction/representation and individual/collective, I want to think about the process-driven sculptural work of three Black contemporary artists—Dean, Rindon Johnson, and Brandon Ndife—and the open-ended ways their work critically explores the social production and circulation of race through its formal qualities. These sculptural practices “talk back” to what Victor Anderson calls “the blackness that whiteness created.” I’m interested in the articulation of networked perception and immaterial spaces, as well as what kinds of practices are available that reject convenience society’s demand for legible aesthetics, trauma trafficking, and fake deep shit.

Process-based abstraction won’t save us. But when the world or worlds are ending (or, in another sense, ended in 1440 when the Portuguese reached West Africa), it’s important to consider that certain abstract practices can be nourishing. Abstract practices—like the emancipatory social experiments in living free called marronage (maniel, quilombo, palenque, and other such settlements of escaped Africans and Amerindigenous Caribbeans); syncretic religious practices that retained African traditional faith and thus allowed the Haitian Revolution; but also more mundane practices such as food, fabric arts, agriculture, and social and spatial architecture—have allowed for the survival of many (not all) Black people on the mainland and in diaspora. I don’t mean that we/I should trust the process. I mean that we need to abandon Abrahamic understandings of salvation (the eschatological idea that “we are living in the end times,” repeated for thousands of years) and the dichotomized thinking that is part and parcel of secular modernism. As a means of consciousness transformation, art can serve this purpose, and has ties to gnostic tendencies repressed and governed by Abrahamic literalism. Indeed, “art” as a post-Enlightenment concept represents a secularization of much European activity once considered worship (such as sacred poetry and song, church fresco painting, and scribal labor).

Abstraction is that which may or must be less than or not only concrete, that which may or must require more cognitive effort than usual, that which may or must be obscure or occluded. The generic is that which is not necessarily or not only specific, but, following Dean, I use the term here in a more technical sense. Process is an ongoing set of activities or ideas that may or may not result in objects or other benchmarks and byproducts along the way.

Left: Aria Dean, (meta)models: fam, stigmata, 2019. Two-way mirror glass and metal, 29 × 17 13/32 × 1/4 in. Right: Aria Dean, (meta)models: fam, first unit, 2019. Two-way mirror glass and metal, 40 × 16 × 3 in. Installation view, (meta)models or how i got my groove back, Chapter NY, March 31–May 5, 2019. Courtesy of the artist and Greene Naftali, New York. Photos: Dario Lasagni.

With respect to technological reproduction, and spurred on by the false dichotomy between abstraction and figuration imposed on Black artists, Dean argues: “The history of black people in the Americas … is intrinsically bound up with the history of mass media and photographic and moving images. … The very notion of blackness itself is an image that precedes any subject’s self-identification with it as such—the product of the European colonial imagination,” imposed on people of a certain range of skin tones, hair textures, facial features, and genealogical histories in order to restrict our subjectivities for profit, pleasure, and whatever else, with the darkest and most phenotypically Abantu women and gender-nonconforming people facing the brunt. Hortense Spillers writes: “The human body becomes a defenseless target for rape and veneration, and the body, in its material and abstract phase, a resource for metaphor.” Kandis Williams describes this European violence well when she says that European artistic forms “work to simultaneously elevate the Black body to a symbol of avant-garde art objet (the Black nude or Black African mask) and collapse the Black body into just another corpse.”

In her essay, Dean builds on François Laruelle’s idea of the generic as “an average universal or middle ground between the One-All and singularity or individuality” that may allow us to “get out from under the dialectical burden that perpetually distills the polarities between representation/abstraction.” She argues that Blackness, as a sign of negation and symbolic death, is the ur-case of such a dialectical burden; as such, a generic approach can sidestep binaries like abstraction/representation, individual/collective, and (we could add) art/non-art. These dichotomies conceal the networked affect at play in the symbolic domain of racial thinking—it’s a priori for the subjective individual, rather than its product. The intersubjective fact of Blackness exists between people as well as inside people, but the implication here is that the between is first—a ground for the inside. Individuals racialized as Black can enter into this interstitial generic space, where “interpretation” is understood as surveillance and governance.

Dean pays special attention to postmodern Black women’s conceptual portraiture, analyzing still image works by Lorna Simpson and Sondra Perry and a moving image work by Martine Syms. Her argument also applies to Black sculptural practice. Dean’s own work provides a good example with the (meta)models series (2019), where she constructs wavy humanoids from two-way mirror glass, indicating the way the imago of Blackness is reflective, a model of a model. In her solo show at Chapter NY, the (meta)models were accompanied by a dummy security camera faux-surveilling the audience as they encountered various iterations of their own gaze, returned to them by viewer-like forms. Blackness emerges in circulation. That which is created by the gaze returns its own gaze, looks back at what is called void and sees substance (though perhaps not essence).

Rindon Johnson, It is Not the Meaning it is the Sound, 2017. Video still. Single-channel 4K video, 7:37 min. Courtesy of the artist.

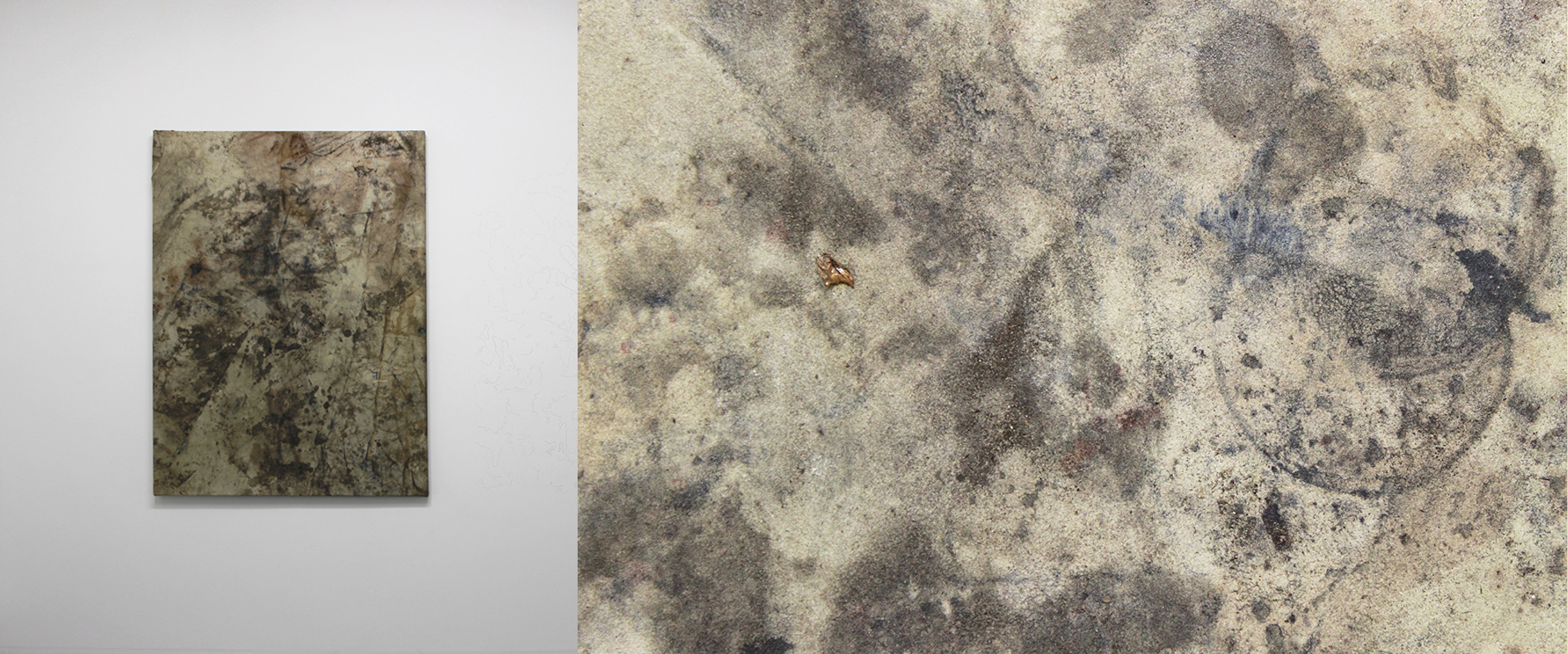

Left: Rindon Johnson, It is Not the Meaning it is the Sound, 2017. Single-channel 4K video, 7:37 min. Right: Rindon Johnson, I don’t think your prayers get over your head. No I see nothing. Heal me. To set, to put. Adults always be asking for hands. What one has to do: flowers on the table or other ordinary business. Between sport and lace is a finger. You don’t usually find a soft voice on the side of the road, I’m sorry for my little out burst. I think any of these guys are interchangeable, I think you need to eat a rabbit and then you’ll understand. The shine creates a gap. He heaps me. I’m in over my head. I’m in over my head. I’m in over my head., 2019. Hide, Vaseline, dirt, gravel, dust, shellac, rope, aluminum clips, dimensions variable. Installation view, Not Total, Paragon Arts Gallery at Portland Community College Cascade, November 8–December 14, 2019. Courtesy of Paragon Arts Gallery and manuel arturo abreu. Photo: Mario Gallucci.

Blackness is produced not only in image but in language. Intuitively, people understand language as something inside the body (Noam Chomsky’s “language organ,” for example). But the “stuff” of language—like words and sentences—exists between people and across times. Working in writing, sculpture, and virtual reality, among other forms, Rindon Johnson explores language’s usefulness for the subjunctive articulation of possible worlds. In one ongoing series, he stains and ages raw cowhide through studied neglect over long periods, co-occurring or culminating with surface application of Vaseline, epoxies, or other media.

The linguistic dimension of Johnson’s practice corresponds to other explorations of narrative in his work, such as in durational VR installations and long, narrativized titles. In It is Not the Meaning it is the Sound (2017), a moving image work combining thrice-repeated process documentation of Vaseline application to cowhide and recitation of poetry in a kind of digital confessional register, Johnson provides something like context regarding the cowhide curing practice: “Vaseline is a byproduct of refining oil or petroleum. Vaseline is used to moisturize skin. Moisturizing is maintenance. Skin gets dry. Leather gets dry. Leather is a skin.” The short, atavistic utterances and linguistic motifs of the writing cajole the reader into easy connections, punctuated with the slaps of Johnson’s hand applying the Vaseline: the sublime, pastoral landscapes during industrialization, cows, burgers, America, war, petroleum (jelly), oil, the Middle East. However, the poietic repetition articulates a certain linguistic density, and deeper motifs puncture the “epidermal” or advertorial layer: Mosul, muslin, Marco Polo, veils, skin, pigment, circulation, value. “Black wood is a byproduct. Methane is a byproduct. I am a byproduct. Leather is a byproduct. Ozone holes are a byproduct.” Abstracting away from things, and the violence in that decontextualization, is key to the undertones of the text. In that lossy transcoding, something happens that begs exploration.

Rindon Johnson, That’s enough ok, I’m of several minds about it. I’d like to sit in a pool but not die in one. Have you ever questioned the nature of your reality? Please it was just a game. Ya know structured dancing. Well it rained too soon. You’re as new as the nation. I mean I brought you here., 2018. Indigo, furniture leather, rust, coffee. Installation view and detail. Courtesy of the artist and King’s Leap, New York.

There are also ethical questions. The breeding of cows for maximum profit and pleasure and other aspects of violent factory farming draw parallels to chattel slavery as well as to the anti-Black industrialization of consciousness, the mind and body made factory in the informatic capitalist context of the West. What kind of creativity is possible in the space of the noxious byproduct? In what ways does this work collude with factory farming? In what ways is it an intervention into the inevitable leather industry? What does “byproduct” mean when, from a larger view, the value of goods in the United States relies on managing huge amounts of waste?

In 2019, I curated a show that included some cowhide works by Johnson. He sent leather to Portland, which we cured on the roof of the former Yale Union (soon to be the headquarters of the Native Arts and Cultures Foundation) for about six months, applying three layers of Vaseline over this period. Right before the show, a white visiting artist felt it was appropriate to move the clearly-marked curing setup and transfer the hide to a resident sandal maker because they “didn’t want the leather to go to waste.” The sandal maker returned the hide to us and apologized, but the situation indelibly marked the surface of these objects, becoming part of the sculptural mass of byproducts that contribute to the appearance and networked meaning of the object. This, of course, is not virtuality, but the narrative dimension of reality, whose application is out of one’s control. The cured constellations on the hide works’ surfaces makes me imagine that my whole world is inside a cow; my sky is the cow’s skin, and as I look up I see the stars as a simultaneous outgrowth and keystone—the basis of a whole structure of synchronicity, but also seeming sketched, like the hesitant marks of a young genius in a moment of self-doubt. Of course, this experience is highly subjective in the extreme.

Left and Right: Brandon Ndife, Öffnung, 2020. Corn husk, resin, AquaResin, earth pigment, enamel, wood, aluminum, 28 ½ × 15 × 15 ½ in. Courtesy of the artist and Bureau NY. Photos: Charles Benton.

The etymologies of both “chemistry” and “alchemy” share the Arabic “al-kimiya,” which came from the name for predynastic Egypt, KMT or Kemet, meaning “Black Land.” As such, the alchemical process remains implied in certain artworks’ curious stasis or quiet. Sculptor Brandon Ndife’s debut solo show at Bureau in 2020 contained floor- and wall-based sculptures where the interiors of built domestic objects transform into earthen, decayed temples. Cast vegetable forms, ceramic plates, corn husks, hemp, earth pigment, sea moss, porcelain, and many other materials dramatize the midpoint of an alchemical process rendered skillfully by the artist with sharp, geometrically pleasing bursts of blue, green, red, and yellow. The inevitability of decay or rot sounds a countermelody of vital force or resilience: no new energy or matter is ever introduced into the world-system; initial inputs are only transformed constantly across evolutionary time. Etymology itself, for example the etymology of “alchemy,” points to this eternal, essence-less rotting structure of meaning. Originating from a functional design context as furniture, however obscured, the molds and casts in Ndife’s sculpture broach a more ambiguous space. On a purely formal level, the sight of a work like Hygge (2020)—which in Danish means a sense of coziness at home—evokes the use of crockery in Brazilian Candomblé ritual as a vessel for sublimation, as well as the luck of the draw regarding which specific Afrodiasporic ethnic groups were able to retain the oracle. Regardless, one must attend to the struggles for meaning among those who pursue an oracular mode after the oracle was lost, as well as those who may feel doubt even though they preserved the lineage.

In Ndife’s press release, there is a cabinet character who speaks, though it decides not to share “Anything / Of / Myself / With you / At all.” Here we register the impossible refusal of an object made for use. What choices does this cabinet really have? The expectation that a functional commodity should talk or otherwise have phantasmagoric or interactive properties has to do with the ur-commodity, the African person displaced and enslaved as chattel, detribalized, natally alienated. Even Marx’s description of the way the commodity relation conceals labor exploitation relies on reducing the Middle Passage, its survivors, and its victims to metaphor: “wage slaves” are under the spell of “commodity fetishism.” Of course, by 1460, the Portuguese Catholics had already distinguished fetisso as worse than idolo: they used the former to name “capricious” African spiritual and material practices such as believing in the agency of an object. If the talking furniture refuses verbal intimacy, the forms Ndife makes can be read as ritual occlusion or (like Animorphs book covers, some of my favorite aesthetic gestures) a type of mid-transition snapshot.

Brandon Ndife, Hygge, 2020. Plywood, cast foam, earth pigment, AquaResin, resin, enamel, ceramic plates, 38 ½ × 25 × 21 in. Installation view and detail. Courtesy of the artist and Bureau NY. Photos: Charles Benton.

While I frame this analysis of the works of Dean, Johnson, and Ndife within the Black generic, it’s not a totalizing frame. The Black generic is itself one among many struggles to find a liminal or networked space between poles of binaries like figuration/abstraction, individual/collective, art/non-art, art/ritual, and content/context. To read their works as figurations of a network of sedimented meanings evokes the trees of formal syntax and decompositional semantics, which contra Wittgenstein are not pictures of the world but, ostensibly, representations of psychological states. The aesthetic lineages and presents of these process-based abstractions, whose underlying force is a perception of immaterial rhythms, move parallel to and against a Blackness that whiteness made (Victor Anderson); a Blackness of “the same old image problem” (Ulysses Jenkins); the circulation of a bruising imago. Dean cites Blake Stimson’s reading of the photography of the Bechers as “a process that connects one image or one encounter or one object to the next and the next and the next (‘as in Nature,’ they say), rather than using photography to exercise the analytical powers of isolation, definition and classification or even detailed description and understanding.” In this light, Black generic sculptures feel like event horizons, indicating how a trace of the true thing remains even in the last instance of all the copies. x

manuel arturo abreu (b. 1991, Santo Domingo) is a poet and artist from the Bronx. They studied linguistics (BA Reed College 2014). abreu works in text, ephemeral sculpture, and what is at hand in a process of magical thinking with attention to ritual aspects of aesthetics. They are the author of two books of poetry and one book of critical art writing. Their writing has appeared at Rhizome, Art in America, CURA, The New Inquiry, Art Practical, SFMoMA Open Space, AQNB, etc. abreu also composes club-feasible worship music as Tabor Dark, with thirteen releases to date. They also cofounded home school, a free pop-up art school in Portland in its sixth year of curriculum. Recent solo and duo shows: Portland State University, Portland; Yaby, Madrid; the Art Gym, Portland; Open Signal, Portland; Institute for New Connotative Action, Seattle. Recent group shows: Kunstraum Niederösterreich, Vienna; Superposition, Los Angeles; Haus Wien, Vienna; Veronica, Seattle; Felix Gaudlitz, Vienna; Critical Path, Sydney; Studio Museum in Harlem, New York; NCAD Gallery, Dublin; online with Rhizome and the New Museum; Centre d’Art Contemporain, Geneva. abreu has also curated projects at: Yale Union, Portland; Center for Afrofuturist Studies, Iowa City; SOIL, Seattle; Paragon Gallery, Portland; old Pfizer Factory, Brooklyn; S1, Portland; AA|LA Gallery, Los Angeles; MoMA PS1, New York.