For Dispatches, Dakota Higgins ponders the depths of Christina Catherine Martinez’s Aesthetical Relations, a comedy and theory extravaganza performed at REDCAT on November 11, 2022, from behind a very thin fourth wall.

Maybe I’m crazy—that’s what they call theory damage, right?—and I’m just looking for things that are not actually there. . . . Am I no better than the Mexican Catholic ladies of my youth who were always finding the face of Jesus in a tortilla? Am I no better than the people who find the face of Jesus in a Kit-Kat bar, or in some stain on a drainpipe?

–Christina Catherine Martinez, Aesthetical Relations

Animation still by Christopher Richmond.

Cue lights.

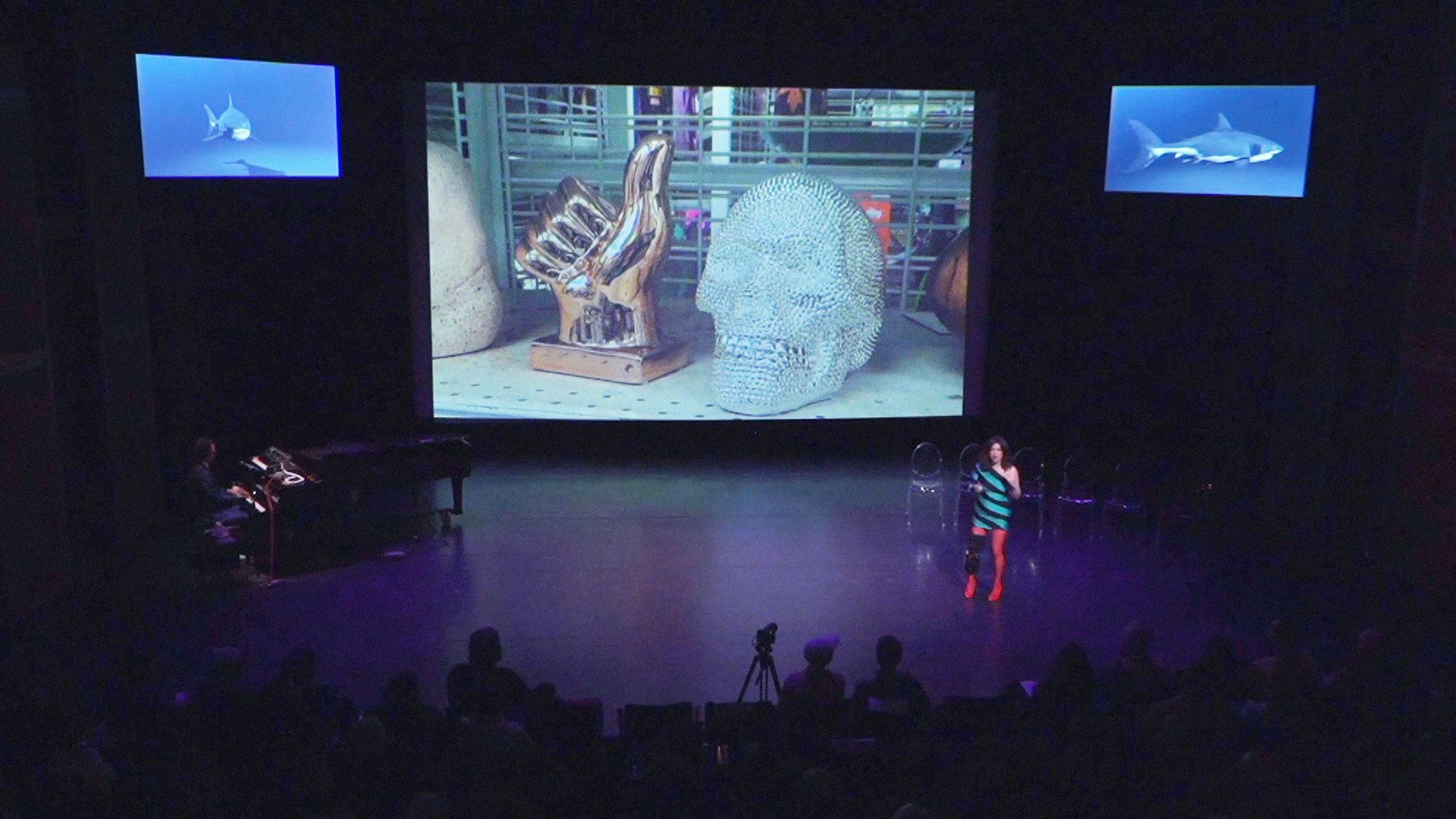

On monitors high above stage, two animated sharks circle ceaselessly, flanking a large projection of a mildly mangled spaceship’s interior. Through a porthole, we see the twinkling of stars and the glow of galactic dust. A peculiar juxtaposition, this outer space and this sea—two environs whose profound depths register in inverse ways. In space, the deeper you go, the farther you get from Earth, while in the ocean, depth means proximity to its core. In the deep blue, you see sharks from the hulls of subs and ships, and heavenly bodies from celestial capsules in the deep black. At least that’s how it looks on TV.

Cue piano.

Martinez enters house left, past a noodling pianist, crosses the stage, and retrieves, with an exaggerated glance at her audience, the remote slide advancer hidden in the unlit periphery. Her journey is stifled, “shackled” as she is by a burdensome “metaphor”: the brace around her right leg. “Hello?” she asks, testing her mic. “Hello,” she responds. “Hi.” The shuttle’s guts are gone, replaced instead by transcriptions of these curt salutations, but the sharks stick around, swimming, swimming…

“Welcome to Aesthetical Relations, everybody!”

Conceived in 2016 as a talk show, Aesthetical Relations has taken the form of several kinds of performance, as well as a book of essays. Martinez sees Relations’ eleventh iteration at the REDCAT as “the real beginning.” As a writer, actor, art critic, and comedian, Martinez proves poised to keenly conflate the sunken depths of comedy with the spacey depths of theory. The fusion of the academic and the absurd, the theoretical and the theatrical, the humorous and the hermeneutical—it is this union which acts as the lens (blurry though it may be) through which Aesthetical Relations as a whole should be viewed. This is where critical gesture meets comical jest.

Still from the Aesthetical Relations livestream, November 11, 2022.

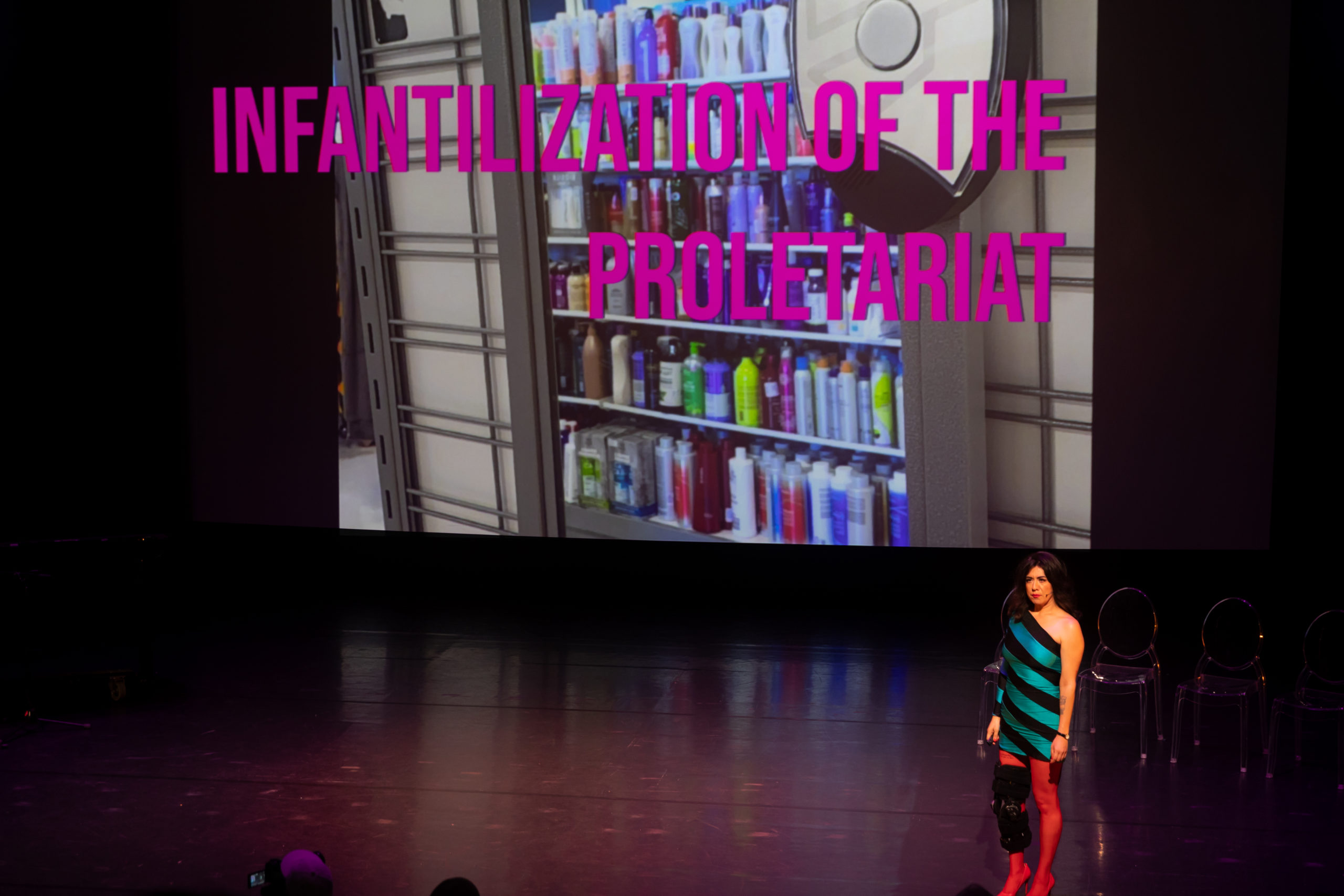

Our Aesthetical journey begins with a theatrically enhanced slideshow presentation—part academic lecture, part stand-up routine. “As theorists, we find signs of history in the banal objects of the everyday. And this is really my Paris in terms of critical engagement,” Martinez claims, gesturing towards an image she took of her local Ross Dress for Less. The following pictures hit in a series of one-two punches: a photo of merchandise at the store is presented and commented upon before a concise textual analysis overlays the image in the next slide. Her assessments assert the “true” meanings of the objects portrayed, while highlighting the absurdity of their very existence. Over an image of a mac-and-cheese-scented candle appears “AESTHETICIZATION OF POVERTY”; “TOXIC MASCULINITY AS PSYCHIC APPARATUS OF THE POLICE STATE / HERO COMPLEX” cuts across a rack of children’s army and police officer costumes. (The effect is not dissimilar to the special sunglasses discovered by Roddy Piper’s character in They Live—a film analyzed by a certain Slovenian philosopher at the start of the pop theory classic, The Pervert’s Guide to Ideology.) “Oh, not me! I’m in the art world! I’m an elevated citizen of the cultural hierarchy!” Martinez mocks. “You’re just as bad as the rest of them,” she declares beneath an image of a plastic skull approximating Damien Hirst’s For the Love of God. The bright red letters land: “ART WORLD POETICS AS COVER FOR OFFSHORE FINANCE.”

Though her subject is intentionally base, Martinez’s style of evaluation neither “elevates” the joke to the status of “legitimate discourse” nor tosses critical thought beneath the soles of a clown’s shoes. Instead, two greater truths are expressed: that all things laughable harbor a trove of latent meaning, and that academia itself can be a bit of a funny business. Her study reminds us that astute observation, cultural literacy, and a cultivated acuity are required on the parts of both comedians and critical theorists, and that comedy is best when incisive commentary is one and the same as a good ol’ joke.

Christina Catherine Martinez, Aesthetical Relations, November 11, 2022. Courtesy of REDCAT, Los Angeles. Photo: Angel Origgi.

The show culminates in a dysfunctional panel discussion, featuring Martinez, comedians Todd Glass and Lizzy Cooperman, Waldo (of “Where’s Waldo?” fame—a most clever audience plant clad in red and white striped shirt and beanie—played by Cam Gavinski), Slavoj Žižek (James Adomian), and a “SPECIAL GUEST” (on which, more later). A stand-up routine, advertisement, trailer, or other bit introduces each panelist. In time, the assembly of characters renders absurd the common oddity of the panel discussion in art world contexts. How funny is it that we, as artists, writers, critics, curators, and the rest, regularly watch people have a conversation? That we look at discourse? As artworks are typically regarded as a visual means to spark, instantiate, or further a “conversation,” in the staged lecture or panel, a conversation itself becomes visual—a thing to be looked at.

In Martinez’s own words: “The interview is this very performative thing, which is where the term ‘Aesthetical Relations’ comes from… You’re participating in this dynamic, but it’s also for the benefit of [a] spectator that’s not participating.” In Aesthetical Relations, Martinez heightens our experience of this performance by poking fun at it. The content of the conversations between performer-guests is deemphasized to near-irrelevancy. Shambolic exchanges break the fourth wall so regularly as to render it a ruin. As relatively little is said during the panel, the true conversation happens between the forms and conventions of art discourse (the lecture, the interview, the panel, et al.) employed throughout. These forms themselves serve as the objects to be considered by the audience.

Other artists have examined the presentation of discourse, often through the meta form of the lecture-performance. Notably, while the lecture-performance utilizes the forms of (art) discourse themselves to critique and expand the possibilities of that discourse and those formats, the finished product tends to exist as a speech. Even Andrea Fraser’s brilliant Men on the Line: Men Committed to Feminism, KPFK, 1972 (2012/2014), wherein the artist reenacts a panel discussion by herself, is ultimately a monologue. Far rarer is the artwork that directly presents the form of the conversation as such. It’s easier to control the content of your work when you’re its sole executor; other people are unpredictable. And yet it is precisely the unpredictability of third parties which proves to be the most generative dimension of Relations’s presentation.

Christina Catherine Martinez, Aesthetical Relations, November 11, 2022. Courtesy of REDCAT, Los Angeles. Photo: Angel Origgi.

Indeed. “Our next guest is a very special guest,” Martinez continues, “because they don’t know that they’re a guest… But I really hope she’s here, because she’s supposed to be reviewing this show for an art magazine…”

“Neat,” thinks I, naively, “someone else is here to review the show, too…” As I scan the audience for the next possible performer, my curious, relaxed attention is shaken by—“Dakota Higgins? Are you here? Dakota Higgins? Come on down!”

Too surprised, confused, and impressed by the risk taken by Martinez to be embarrassed, I take my seat on stage. She confirms for the audience that we haven’t met prior to that moment. (We haven’t.) “This is unprecedented,” blurts The Most Dangerous Philosopher in the West. “A violation not only of the fourth wall, but of the separation of the critic and the criticized.”

“It’s important for a critic to have multiple perspectives,” Martinez reminds me, her tongue in her cheek.

“Note the unexpected awkwardness of the gazing eyes of the critic who himself is now found to be in the spotlight. My God! It’s Brechtian in its brutality!” ersatz Žižek insists.

While a select few from a standard panel’s audience may be called upon to ask their own questions and make their own comments, the Q&A rarely rises to the level of true audience participation. The audience is more often used to wring the last drops of insight from the featured speakers.

Indeed, the move seemed too good to be true: after the show, several people asked me whether I knew what Martinez had planned, and more than one insisted that I absolutely must have known. After all, what would have happened if I hadn’t showed up? The artist, a seasoned improviser, would have been ready. As Martinez informed me later: “REDCAT is accustomed to precision, but Aesthetical Relations has a lot of what I call ‘pockets of air,’ where I simply don’t know what’s going to happen. There’s a mix of carefully crafted elements and authentic risk, things that might fail, or compromise the show… I like having those stakes in place. The twenty-four hours leading up to the show are the only time I regret it.”

Christina Catherine Martinez, Aesthetical Relations, November 11, 2022. Photo: Michael Gross.

As the true audience plant, Waldo is the foil to my role as critic in Martinez’s play. Whereas Waldo was a character (and an accessory to the joke) before he came on stage, I became one after; whereas Waldo’s character is defined by being looked for and looked at, mine does the looking-after. Together, we constitute a microcosm for the audience’s relationship to the work; a joke about looking, about an ostensibly astute audience preoccupied with looking both “for” and “at” meaning and discourse. Like the mug of Jesus upon a drainpipe, Waldo only appears before the discerning eye—and in a venue like the REDCAT, a Los Angeles art world staple and offshoot of CalArts, one of the country’s most (hi)storied art schools, the quip that “everyone’s a critic” rings true.

Animation by Adam Gerber.

As I retrace the arc of the show, I recall the circling sharks—the animated sentinels that never left the stage. Were they meant to comically render the archetypically harsh gaze of the critic? To address the audience as surrogates for the show’s antagonism? Or were they circling the panelists themselves, reinforcing the audience’s expectant gaze upon the performers, eager to feed on whatever was presented to them? “Feast your eyes,” we say. But my inclusion as both feaster and feast destabilizes the distinction between hungry subject and consumable object. As a titular inversion of Relational Aesthetics, Aesthetical Relations performs a conceptual inversion as well. Rather than rendering a work whose aesthetic significance (“beauty”) is rooted in the relationships it actively facilitates between individuals, modeling a relationality that reverberates outwards into the world, Martinez crafts a scenario wherein relationships are aesthetic objects, framed by the stage. Hers is a relationality that recedes, pulling the “outside world,” its critical gazes and gazers, in… literally.

To ambiguate spectator and spectacle—the critic and the criticized—is to invite a holistic analysis, one in which the analyzer is always already implicated in their own analysis. At the conclusion of her study of the Ross, Martinez epitomizes the practice Relations preaches with the series of rhetorical questions that open this text. If only the sharks could learn her lesson. They stick around, swimming, swimming, but never manage to catch anything. If they could take a moment to see themselves, maybe they could stop going in circles. But they can’t. All they see is prey. Maybe Martinez’s minions provide the audience with a fair and final warning: Don’t be a shark. X

Jesus on a drainpipe.

Dakota Higgins is an artist, writer, and musician based in Los Angeles. He runs the experimental music venue The DMV, LA (aka The Departure from Music Venue[s]).