My research and practice over the last couple of years have focused on weaving voices like mine into a culture that has historically erased and ostracized LGBTQI+ people. In confronting the history of my birth nation, Albania, while grappling with assimilation as an immigrant in the United States, I seek to build bridges between place and time while simultaneously disrupting existing conventions. For me, this liminal space of double consciousness, a sense of belonging to either land, runs through each thread of each qilim. Work from this series appeared in Biddy’s Garden at Transformative Arts in Los Angeles from February 18–April 9, 2022.

Silvi Naçi, Untitled (pussy), 2022. Wool, natural dyes, 39⅓ x 59 in. Photo: Silvi Naçi.

In the nearly 500 years Albania was under Ottoman rule (1385–1876), its people witnessed a repressive shift in religious ideology and cultural development. After liberation from the Ottoman Empire, and during the communist regime that followed, same-sex intercourse was penalized with long prison terms, death, bullying, ostracism, and expulsion from society. Albania decriminalized consensual same-sex sexual relations in 1995, albeit nominally, as the LGBTQI+ community suffers from extreme violence to this day. Then, in 1997, civil war broke out as a result of a national Ponzi scheme, leaving the country in even more dire economic circumstances than before. Years of collective trauma, the communist legacy, dreams of capitalism, and the desire to associate with the West in order to gain higher status in society have all left the country in deep poverty and extreme corruption, with no state support towards reconstructive justice or reform.

I was ten years old during the civil war. Due to continuous gunfire, we did not go to school for one year, and my sisters and I spent our days indoors. It was during this time that I began to understand my sexual identity. I felt differently than other kids my age, a feeling I could not express openly. In 2001, we finally escaped the war zone and moved to the United States. Convinced that we would never live in Albania again, my mother packed everything we could need in our new life, from traditional decorative objects to the qilime (tapestry, or kilim in Turkish) displayed throughout our home.

In Communist Albania, the average home contained decorative objects and furniture derived from historic Ottoman and Middle Eastern craftsmanship. One only needed to pay a visit to an Albanian family like mine to witness such objects curated almost like an exhibition of our people’s art. In each room of the home, a qilim would tie elements of craft and interior design together into a marvelous setting for gatherings.

Nebije’s studio in Zogaj, Albania. Photo: Silvi Naçi.

Many able-bodied women were assigned work in artisan cooperatives producing wool qilime and sixhade (carpets and rugs), becoming the most faithful interpreters of this national tradition. Historically produced in the former Persian Empire, the Balkans, and the Turkic countries, the qilime can be purely decorative or function as prayer rugs. In Albanian, the qilim can also be referred to as a shtroje (cover), assuming the meaning of a floor covering. This is a particular site of interest for me, as shtroje alternatively suggests an obedient, quiet woman who obeys her father or husband and makes no noise or fuss.

Shtroje / Shtruar: spread. Të jesh e shtruar: to be paved, to spread. Të jesh grua e shtruar: to behave, to spread yourself thin, essentially following patriarchal rules.

This word and its various meanings intersect in my first queer experience, sitting on a qilim, messing around with someone my same age and sex, and the shame of being caught by my older sister. I kept this a secret from the rest of my family. I arrived to my own sexual identity on top of this national treasure, the qilim, in a country where queer bodies were punished by jail and stoning.

At the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, in lockdown in my home in Los Angeles, I frequently returned to that secret memory. I began considering my relationship to my Albanian heritage, specifically in regard to this secret, in which my queer identity met my cultural one. I found an inclination towards objects within our homes, the domestic spaces that host objects of desire, tradition, and culture. I began drawing qilime that celebrated queer narratives by focusing on quotidian domestic moments with my wife while juxtaposing them with traditional Albanian motifs.

Nebije enjoying our finished piece on her balcony in Zogaj, Albania. Silvi Naçi, Untitled (grapes), 2022. Wool, natural dyes, 39⅓ x 59 in. Photo: Silvi Naçi.

I considered a myriad of options to begin fabricating qilime, including teaching myself; learning from the elders; getting them made in Hotan, China, where qilims date back to the fourth century; or even having them mass produced. None of those avenues would have been tantamount to cooperating with weavers in Albania, the work of their hands intertwined with mine. It is imperative that this work and its process are realized in tandem with them, allowing my narrative as a queer Albanian person to be visible through the hands of craftspeople that have steadfastly preserved decades of traditional practices and cultural cornerstones during times of dictatorship, oppression, and war. As I consider all the voices that have been silenced, this work is where I am able to weave my story into that of my nation’s.

Vjollca holding up a finished qilim. Silvi Naçi, Untitled (blueberry), 2022. Wool, natural dyes, 39⅓ x 59 in. Photo: Silvi Naçi.

In early 2021, an artist friend in Kosovo introduced me to Nebije and Vjollca, who have both practiced the craft of qilime weaving since they were fourteen years old. Nebije lives in Zogaj in the northwest of Albania; Vjollca lives in the historic town of Krujë in north central Albania. After the fall of Communism, when the artistic cooperatives shut down, businesses became privatized. Both women bought their looms from cooperatives to build their home studios and began teaching other women how to weave. They initially began taking orders for wedding dowries and commissions from clients who wanted to replicate designs from magazines in the traditional Albanian qilime. Nebije built her home studio in the hills of Zogaj overlooking Shkodra Lake and Vjollca opened her own store where she often employs women in poverty.

View of Shkodra Lake from Nebije’s balcony. Photo: Silvi Naçi.

Women from Zogaj working on a qilim together. Photo: Silvi Naçi.

After a year of remote collaboration, we developed a deep connection. Nebije and Vjollca were excited to weave unfamiliar images. My illustrations, filled with queer and botanical imagery, domestic and private scenes, passed through their eyes and hands as they calculated each curve, color, and shape to fit within a grid of square centimeters. Each qilim is made from local wool, some from the city of Fier where I was born, and colored with natural dyes from plants the women grow in their gardens.

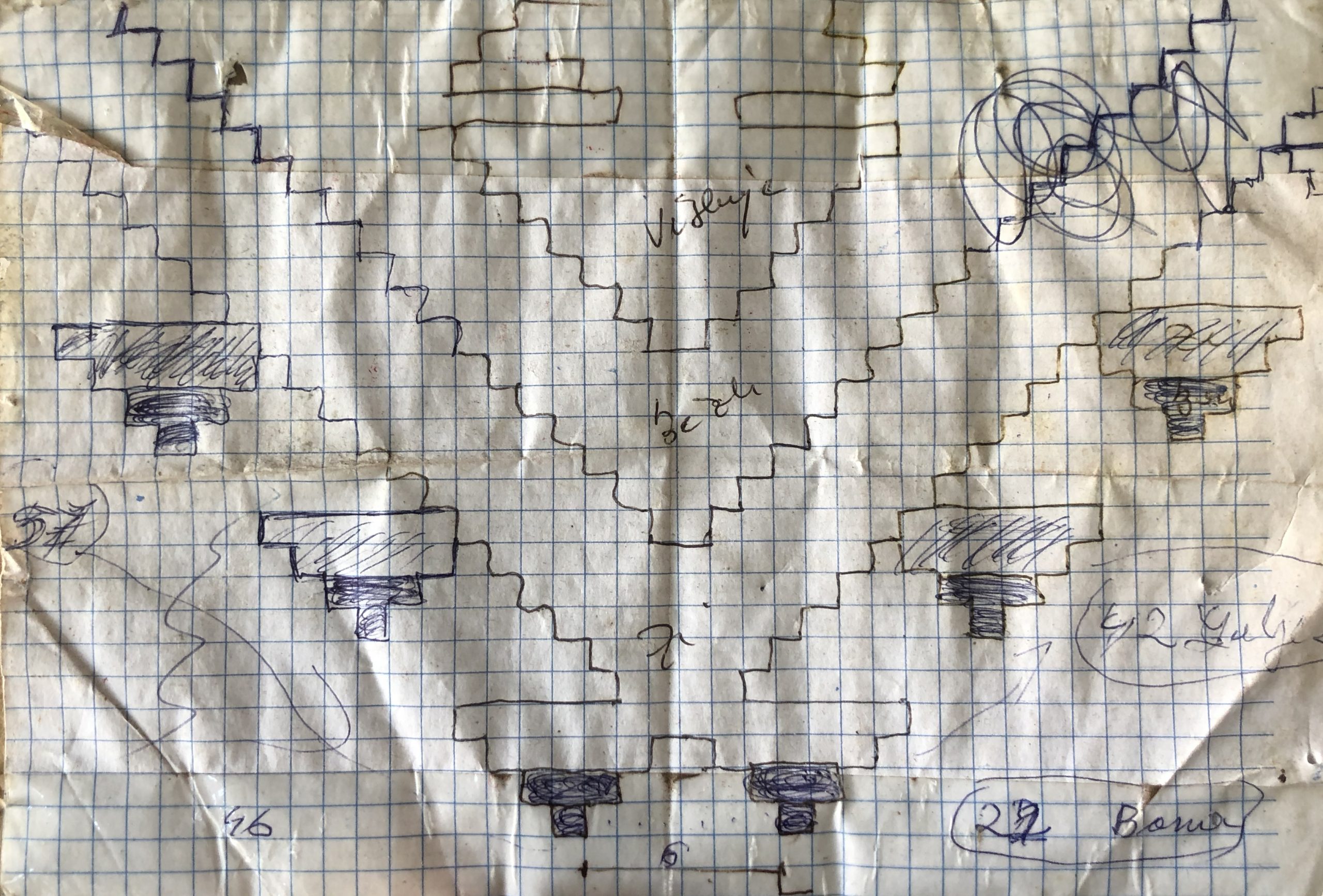

Detail of a technical drawing for qilim production. Photo: Silvi Naçi.

Depicting queer nude bodies in relationship to traditional Albanian designs made me nervous at first. I wasn’t sure how the women would interpret the drawings, and if they would even agree to make them. I knew that, as traditional Muslim Albanian women, they would most likely never be in dialog with a queer Albanian artist living in the United States. This was the opportunity of a lifetime. Vjollca and Nebije convey my queer narrative through their labor—across land, sea, and time. As a writer, interchanging between five languages, I am always in the process of translating. The weavings document the negotiations Vjollca, Nebije, and I make as we build these works, while the qilime themselves serve as catalysts of other translations—between hands and material, drawing and weaving, my dialect with that of the elder weavers’. x

Silvi Naçi, Untitled (with olives & lemons), 2022. Wool, natural dyes, 39⅓ x 59 in. Photo: Silvi Naçi.

Silvi Naçi is an artist and writer working between Albania and Los Angeles. Their interest lies in the subtle and violent ways that decolonization and migration affect and reshape people, language, gender identity, and social and cultural dynamics. The author wishes to thank Vasilika Laçi, a human rights activist living and working in Tirana, for proofreading this essay.