For the eXhibitions column, Matt Siegle talked with Jules Gimbrone in their installation, Trinities, on view at the Cohen Gallery at Brown University from November 4–December 11, 2021. Gimbrone is currently included in Lifes, curated by Aram Moshayedi, at the Hammer Museum from February 16–May 8, 2022.

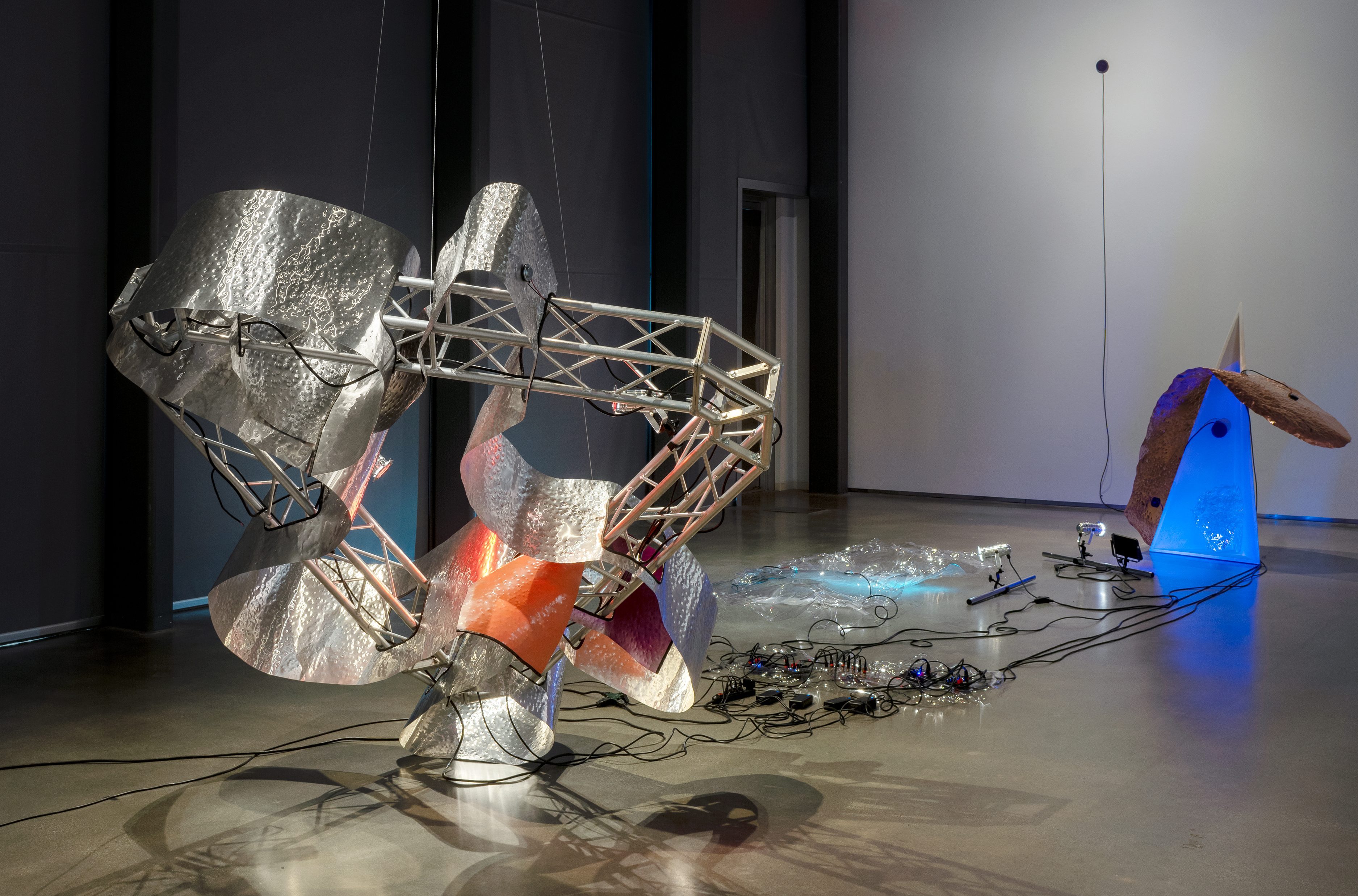

Jules Gimbrone, Trinities, 2021. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Installation view, Trinities, Cohen Gallery, Brown University, November 4–December 19, 2021. Courtesy of the Brown Arts Institute. Photo: Scott Alario.

MATT SIEGLE: Let’s start by walking around. This is one artwork, correct?

JULES GIMBRONE: The whole piece is called Trinities [all works 2021]. But each entity has a title, too. This photographic triptych is called Trinity, these sculptures are Interpenetration 1, Interpenetration 2, and Interpenetration 3. And the two wall pieces are called Human Time. It’s like an orchestra, five different instruments that could play by themselves but have a different meaning when they’re playing together.

MS: My experience of the sound and the objects is very spatial. The most obviously spatialized elements in this system are the two wall objects. I guess they’re speakers?

JG: Transducers. A regular speaker vibrates air to create sound, and transducers actually vibrate the material that they are on. So instead of vibrating air, the big pucks on the wall are vibrating the wall and turning the walls into speakers. They’re transducing the walls.

MS: And they play the sound of fingers snapping, from opposite sides of the gallery, ping-ponging. I’m constantly moved back and forth, across these three other transduction works, one made out of plastic with water, and one made out of…

JG: Aluminum truss and hammered aluminum.

MS: And one that is made out of some kind of wood…

JG: Aquaresin-covered wood with copper and epoxy resin embedded with my hair. All three are resonating sculptures, and you’re hearing the acoustic sound of the vibrating material, like a violin.

MS: The walls become instruments as well.

JG: Yeah. The space colors the timbral qualities and the overtones of the different pitches you’re hearing when you walk around the room; how you’re perceiving them as different is based on the reflections of the walls and the height of the ceiling and all the material in here.

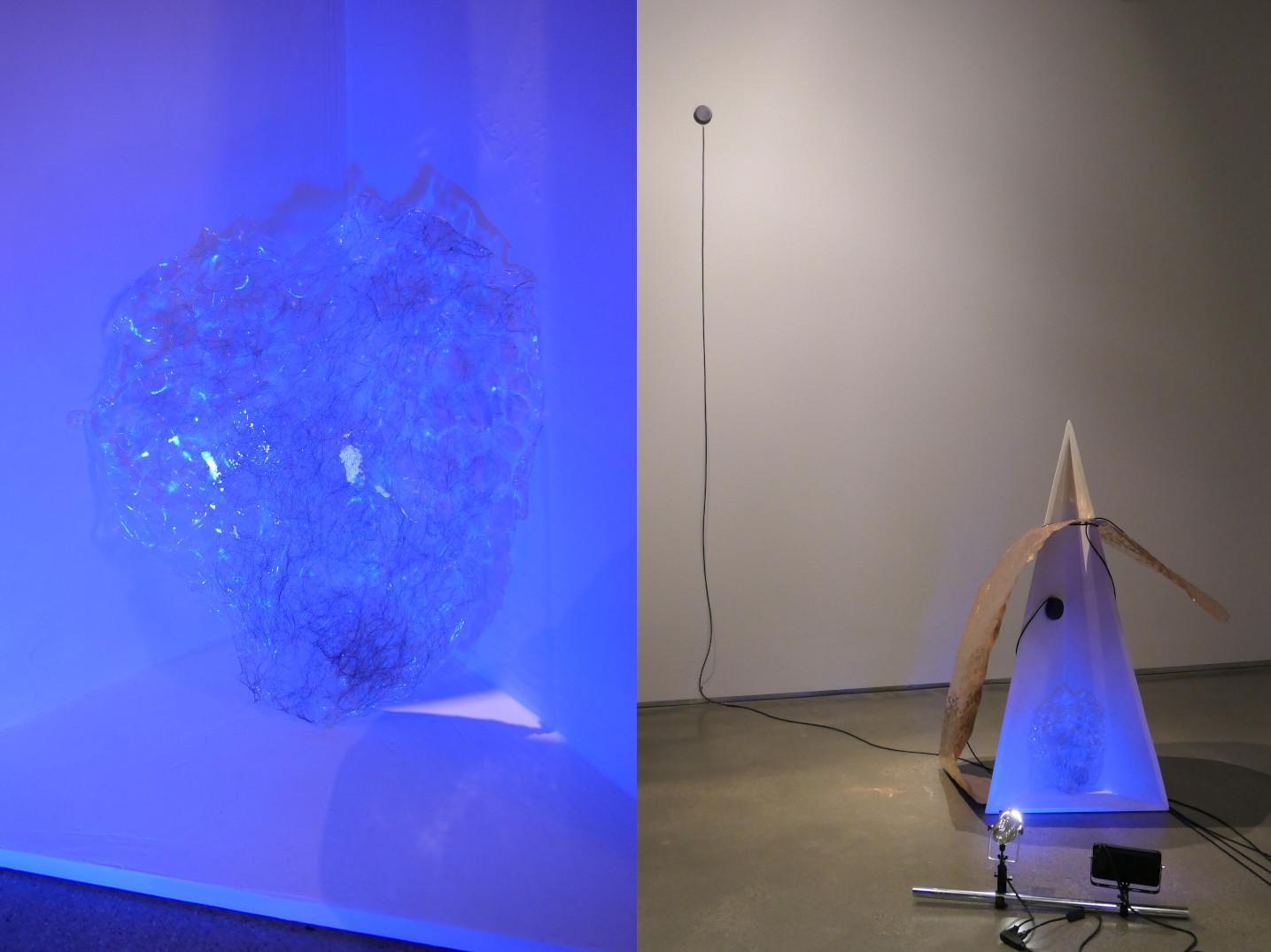

Jules Gimbrone, Interpenetration 2, 2021. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Detail and installation view, Trinities, Cohen Gallery, Brown University, November 4–December 19, 2021. Courtesy of the Brown Arts Institute. Photos: Matt Siegle.

MS: From the different walls, the cycles of snapping fall in and out of alignment with each other, like two different wave forms. Right?

JG: Exactly. It’s a metronome. The snaps keep some kind of time that’s going in and out of phase. I’m trying to think about tempo as a standard—like a unit—that is relational to the one and two beats, this binary of one-two, one-two, one-two.

Humans have a certain capacity in terms of hearing a beat. And if it’s slower than a certain cycle—if you have the one beat right now and then the two beat in two years’ time—that’s no longer a tempo that we perceive. But maybe another organism perceives that rhythm. So tempo is the pace of movement for everything that we understand as human beings, one way we perceive reality.

MS: Okay, so we have a tempo here in—well, I’ll say it’s in human time. And what about these three Interpenetration instruments?

JG: What you’re hearing are sine waves, the purest form of sound, created by an electronic device: they have no overtones, no color, no distortion. All of the texture and color that you’re hearing comes from the material. I’m thinking of them as voicing their own internal times that are outside of this entraining human time.

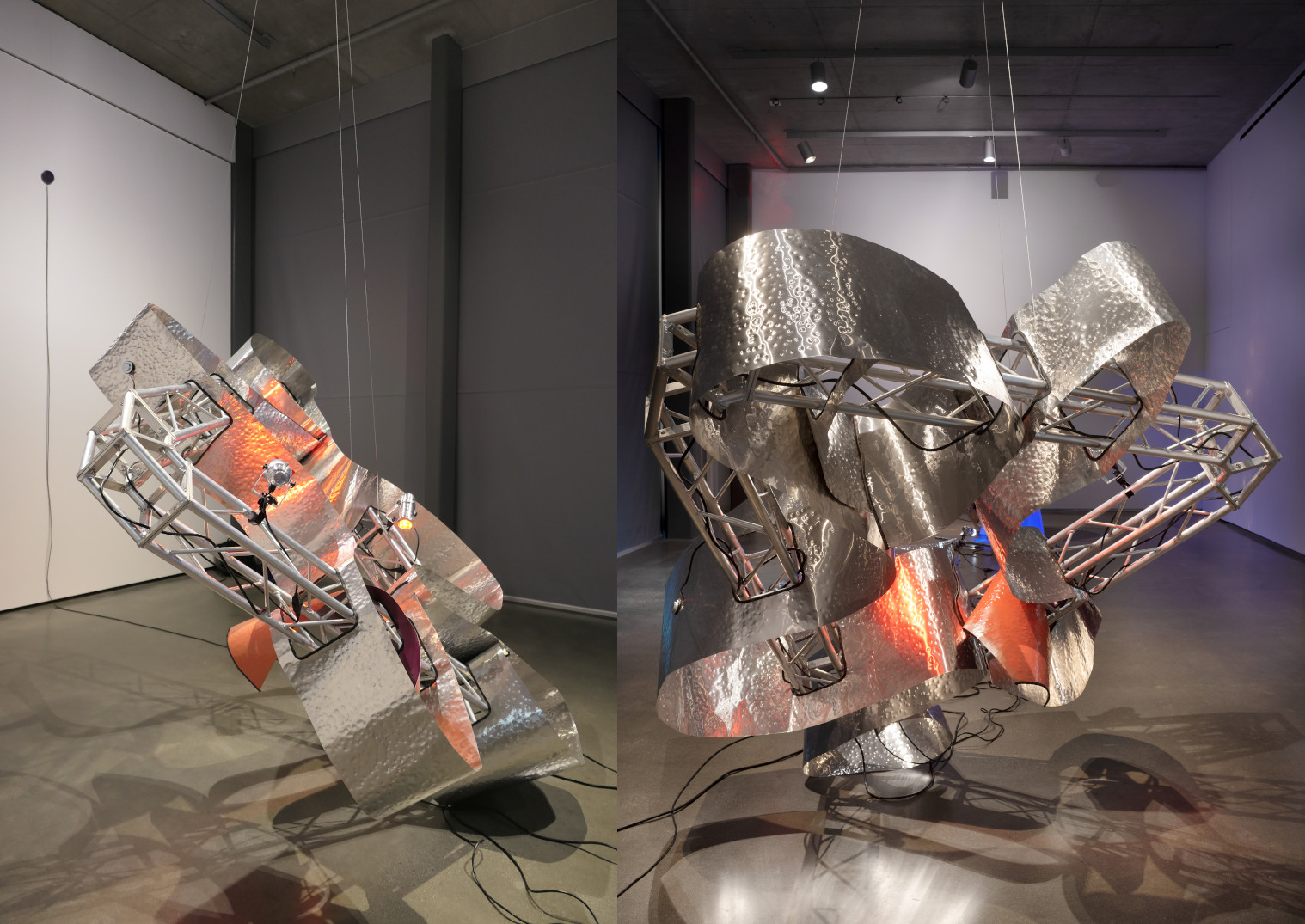

Jules Gimbrone, Interpenetration 1, 2021. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Installation view, Trinities, Cohen Gallery, Brown University, November 4–December 19, 2021. Courtesy of the Brown Arts Institute. Photos: Matt Siegle, Scott Alario.

MS: I’m curious about the embodiment and placement of these objects… or instruments.

JG: I think spatially and in systems when I’m composing. The snaps go back and forth, and they’re high up in the space; Interpenetration 1 hangs, Interpenetration 2 is a standing piece, and Interpenetration 3 is on the ground. That’s basically also how they’re pitched: Interpenetration 1 is more high frequencies, Interpenetration 2 is mid frequencies, and Interpenetration 3 is lower.

MS: It sounds like you don’t see a difference between composing an audio piece and composing an object. The two things are interrelated, or perhaps interpenetrated.

JG: Yeah, exactly. Sometimes a composer will think, okay, I want to make a piece for a string quartet. The violins sit here, the viola there, the cello here. You’re writing for these specific interactions arranged between the instruments. Who knows if all composers think about that because it’s so engendered at this point in terms of what a string quartet is, but that’s something I’m interested in interrogating as a composer.

I also had this idea of creating objects that had this interpenetrative quality, because the concept of the Trinity in Christian theology can also be talked about as interpenetration. So I wanted to create objects with some kind of relationship to material that would cause them to either have to go inside of another object or have some kind of puncture.

MS: Which brings us to this triptych wall work, Trinity.

JG: These are light boxes with four layers of plexiglass printed with visualizations of sound waves. I wanted to think about ways of perceiving experience outside of easily defined subjecthood. And that led me to the concept of the Holy Trinity, which is the only thing from my Catholic upbringing that ever stuck with me because it was so weird—this concept of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit composing a singular entity. It really mapped well onto this idea of the microphone and the snapping hand and the sound wave, an entity based on a contingent set of three nodes or three beings. It’s confusing because the wave form is over everything. It’s the flow of this larger entity, which is sound, which is energy disrupting this easy dialectic of a microphone recording an object and therefore capturing some essential quality of that object.

MS: Well, I think that one of the challenges of this work and your work in general—and also a part of the conversation around queerness and artwork, sound or objects or whatever—is that you are trying to get to something that is somewhat ineffable. You’re figuring it out yourself. And that is part of a daily negotiation of space and subjecthood and objecthood as a queer person and a queer body, while existing in a sort of, uh, a different…

JG: Tempo?

MS: You say tempo. I say spatial physicality. [Laughs.]

JG: Yeah, it’s both. Space-time contingency, or… phase time! We need to get into astrophysics here.

MS: [Laughs.] Well, you’ve talked to me a lot about how Sara Ahmed’s Queer Phenomenology has been an important text for you, and I can easily relate what you are saying about tempo to the way that Ahmed talks about orientation in space.

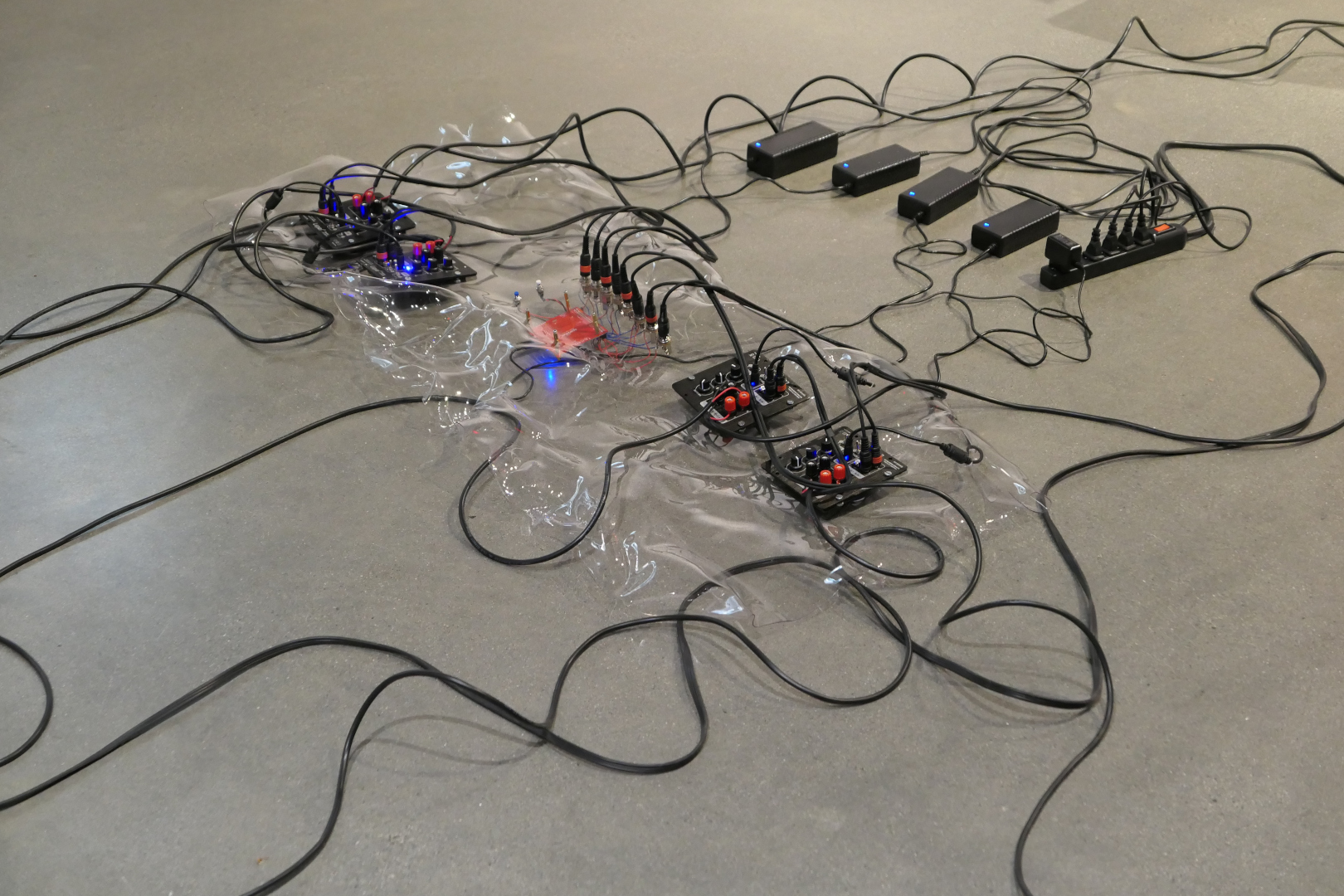

Jules Gimbrone, Interpenetration 3, 2021. Installation view, Trinities, Cohen Gallery, Brown University, November 4–December 19, 2021. Courtesy of the Brown Arts Institute. Photo: Scott Alario.

JG: Orientation is an interesting word, because as you walk through this exhibition, sound is actually physically hitting your body in unusual ways that disorient you from an experience of complacency.

MS: There are some moves that you make in the sculptures that are disorienting—you could even call it a perversion of traditional ideas of sculpture—like how Interpenetration 1 hangs wildly akimbo. Or that the guts of the electronics that generate the audio, the things that artists often hide away, are the most central objects in the entire gallery. And I say perversion without a negative or deviant connotation. A spatial perversion is a turning away from what is normal.

JG: Yeah, or from conventions around music or composition, like the orientation of the audience.

MS: So, to turn the piece on and off you push these buttons in this center plastic brain? That is not a sculpture itself, right?

JG: It isn’t a sculpture. It’s like the motherboard. I really like it as a form and I had to negotiate with it because it does have physical presence in the room.

MS: It definitely does: a minicomputer microcontroller that is embedded into a piece of plastic along with four amps, which then link to the transducers. I’m curious about the decision to embed those objects in this clear rippled plastic that has a gestural quality to it, especially if there’s ambiguity about this as a sculpture. It’s the visibility of what one normally thinks of as unseeable, or again a kind of perversion of the objects.

Jules Gimbrone, Trinities, 2021. Mixed media, dimensions variable. Installation view, Trinities, Cohen Gallery, Brown University, November 4–December 19, 2021. Courtesy of the Brown Arts Institute. Photo: Matt Siegle.

JG: It’s like the Visible Woman. My parents had one when I was growing up—it’s an anatomical model with clear plastic skin, and you can see all the organs and the bones and everything inside. She can get pregnant if you put the little belly on her with the fetus.

MS: [Laughs.] I can’t quite land on it, but there is something about this show that feels very much like being within a body. It’s almost like the whole space is occupied by an artwork that I very physically negotiate.

JG: I think that the physical sensations, those moments where you vibrate, they push you out of conscious thought. It’s not surprising that sound is used in religious and spiritual circumstances to help people get out of their habitual thinking or patterns. Those moments for me are a queering of perception or of a body’s normal routines and thoughts and ways of being in a room, or even ways of being in a gallery. All of a sudden, you’re zapped. x

Jules Gimbrone is an artist and composer who works from a platform of diffused subjectivity, looking to a confluence of biology, technology, and social structures to examine what they call “Trans-Sensing” modalities. Over the last year, Gimbrone presented work at Bortolami Gallery, New York, Brown University, and the Hammer Museum in Los Angeles.

Matt Siegle is a mixed-media artist. He has exhibited throughout the United States and Europe, most recently at Liste Art Fair Basel with Good Weather (North Little Rock/Chicago). He is currently participating in how we are in time and space: Nancy Buchanan, Marcia Hafif, Barbara T. Smith, curated by Michael Ned Holte at the Pasadena Armory Center for the Arts. Siegle teaches sculpture and drawing at Dartmouth College.