For the Re:Research series, we invite artists to present the underpinnings of their work. Here, artist Carter Mull guides us through the turbulent waters at the confluence of art, advertising, big data, and big love.

Tobias Kaspar, The Street, Cinecittà Film Studios, Rome, March 11, 2016. Courtesy of Tobias Kaspar, Istituto Svizzero di Roma, and Cinecittà. Photo: Elzbieta Bialkowska, OKNO Studio.

We live in an ocean of images. One needs only to compare devotees of Fox News to those of National Public Radio to see people living on different planets, not separated by millions of miles of frigid space but by trillions of distinct data points. In 2015, it was estimated that we collectively upload 1.8 billion images a day. That number has almost certainly grown. Yet the turn within media studies has not been toward articulating this vastness. Instead, the focus is on describing how images construct worlds and how worlds construct images. In this dynamic, a series of non-binary questions arise. Hoary battles such as reading the image as a point of connection versus an entrapping illusion comingle with apocryphal possibilities of structural transformations that could seemingly erase forms of work from the planet forever, or at least necessitate human evolution. As this recent bloom of images grows beyond the sublime, individuals are tasked with the work of building their own worlds in lieu of a shared public sphere.

For decades, the advertising industry has been well aware of the worlding function of images. As we are driven to produce our own social forms, large ad agencies pursue the same task. The complexity of such vast amounts of data in our lives complement these advanced pressures of self-determination we all feel; making the need for world building all the more vital, yet perilous. This is felt every day in the social systems we inhabit.

Familial, professional, leisure-based, or otherwise, each social system has its spatial limits, determined by the number and diffusion of engaged nodes, as well as its own unique codes and gestures, not to mention bespoke pressures. In recent years, as a reaction to those pressures specific to the field of art, I made a personal decision: to match my own emotional labor by only working with colleagues rich in sensitivity and conviviality. My previous experience had been the regular exploitation of my emotions by whoever worked by my side, not in solidarity or in antagonistic democracy but in systemically produced hyper-capitalism. This condition still characterizes many “tribes” (to use contemporary marketing speak) within the system of art, a hypertrophied professional network that preys upon the desire and aspiration of all involved, blinding them with refined promises such as redemption from one’s origins. For those like myself that have weathered the piracy of every form of capital (social, emotional, intellectual, fiscal, et al.) while working in contemporary art for more than a decade, what smacks of cynicism may simply be hardened reality. My own take on the fine arts comes mostly from my time working with a narcissistic addict who recently went out of business. Yet as the years pass, my love and energy for art—and the intelligence that surrounds it—warms my heart and softens my edges. Despite the vulnerabilities that desire opens up in all of us, the highly malleable, lexical nature of aesthetics (and its wayward cousin, advertising) is deeply rooted in the human faculty for narrative. Image, text, and a diverse history of affects compose the lexicon we all share while telling, as Joan Didion wrote, “stories in order to live.” Despite my choice to inhabit multiple professional systems, from collaborating with young stylists and fashion workers who party in my studio neighborhood to working with large brands, production teams, and modeling agencies to showing with artist run and commercial galleries, working in a “multiplex network” does not place me outside of my own field (the fine arts). Nor am I beyond the human desire to narrate.

Merlin U. Ward, Director of Cultural Systems, presenting at Sparks & Honey at a daily briefing. Courtesy of Sparks & Honey.

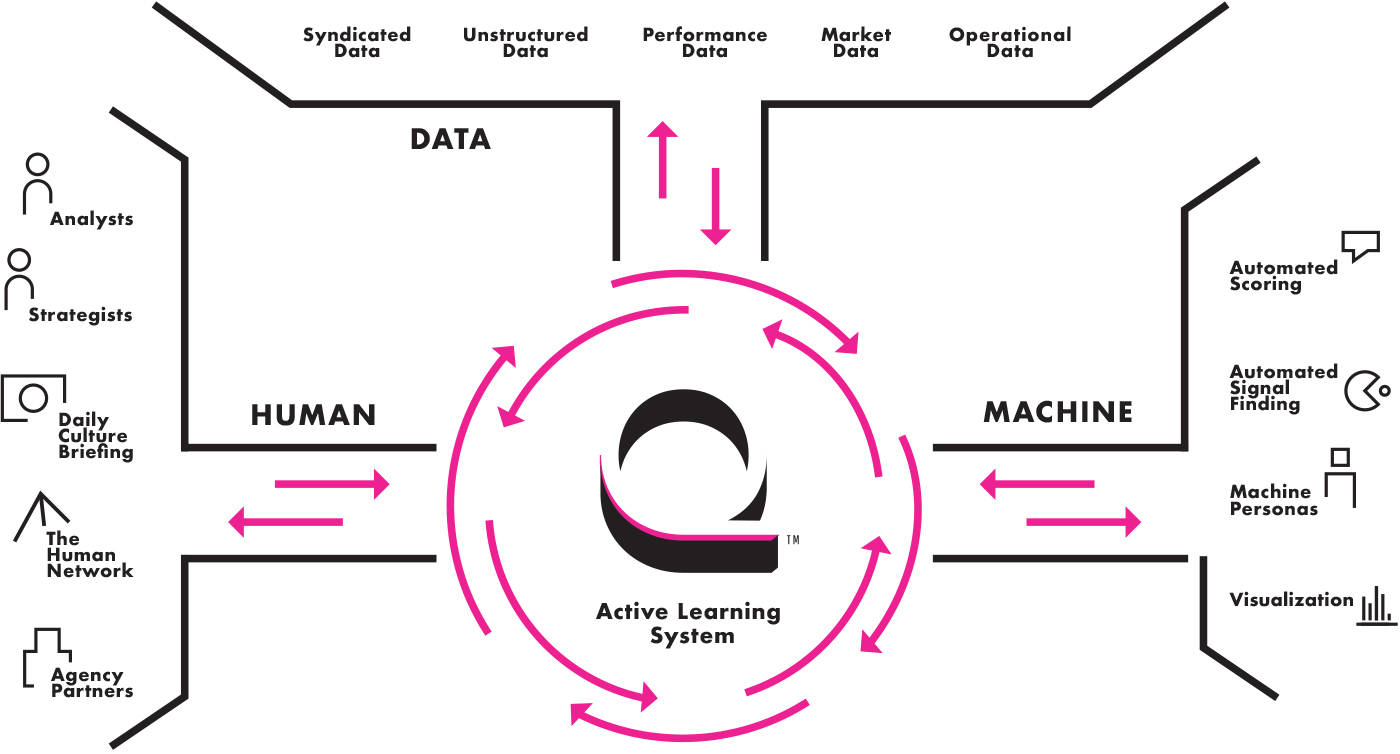

My interest in narrativity and social form drew me to a New York-based advertising cum intelligence agency called Sparks & Honey, known for its cyborgian synthesis of artificial intelligence and human processing known as the Q Network. By attending a number of the company’s “daily briefings” and through formal and informal dialogue with higher-ups at the firm, I gained certain real-time, boots on the ground insights about the diffusion of hegemony into network culture. The corporate speak I encountered in interviews and meetings doubles as a kind of scientificity, which is applied to Sparks & Honey’s clients—notably food and intelligence businesses such as McDonalds and DARPA. Launched in June of 2017, Q, the company’s “cultural intelligence system,” crawls and collects internet content to create a taxonomy of first world culture. From my conversations with Emily Viola, head of cultural strategy at the firm, I learned that Q Network assists with everything from “signal hunting,” a process of turning around data in 24 hours for a given client, to the identification of “pink spaces,” otherwise known as “new innovation opportunities.” By triangulating “cultural currents, changing market dynamics and disruptive technologies,” Q identifies “possibilities for the client.” These discoveries range from predicting a demographic’s desires to coming up with tag lines for the newest wave of 18 to 25-year-old consumers. In discussing Gen Z, Viola noted that “protest is the new brunch.” This is big data at work.

The Q Network. Courtesy of Sparks & Honey.

For decades, a kind of quasi-Marxism was the nomenclature for critical thought in aesthetics. As we experience the societal shift away from class-based stratification governed by a superstructure to “tribes and micro tribes,” the very substrate of Viola’s work at Sparks & Honey, the company provides new insight into applied systems theory. Notably, systems themselves—professional, social, political, or “world”—are more or less autonomous demographics inasmuch as they speak to and from (within) their own constituency. Regardless, certain questions become necessary when examining a given network. For one, what are points of non-viral repetition? Does the sequential structure of repeated messaging produce articulated form? Is it possible to bundle messages together to create weight in an otherwise infinitely light system of communication? According to Claude Shannon’s A Mathematical Theory of Communication (1949), recurring semio-logical moments can be used to determine the coefficient of redundancy within a communicative system. In swimming through the crests of this ocean of imagery, the question is less one of critiquing media dominance by performing the voice of, for example, Time- Life Inc., and more of coming to terms with the structural transformations that surround us, which are completely connected to the entropy that results from such a mass onslaught of data. For Shannon, it is the multiplicity of messages sent and the duration of the distribution of those messages that determines the amount of noise in a system. As this noise becomes deafening, the clarity, or perhaps dumbness (two characteristics which are not always related), must grow so as to cut through the clamor. Ironically, at the same time, connoisseurship must re-emerge as a way to make distinctions within the multitude of engaged nodes on a network. This tension between idiocy and discernment emerges from a technological, structural shift, which simultaneously proposes two opposing options as necessary within the same, corporately controlled system. Is this a flaw in the algorithm or a social force that demands human evolution?

Carter Mull, Working Diagram (a142), 2019, digital asset, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the author and Lundgren Gallery, Mallorca.

Tellingly, Sparks & Honey’s implementation of Q in 2017 coincides with notable shifts in advanced art’s gallery system. At a time when the fine arts have become nearly fully integrated within society (or within the content industrial complex), the inherited, High Modernist ship of intellectual autonomy specific to the field seems to have crashed on the shore of a much broader reality, calling into question the foundations of the art world’s autonomy. What was once the dream life of an avant-garde coterie with an idealistic notion of its audience has become, to some degree, the nightmare of a self-defining social system whose material production is determined by a very narrow client base. Unfortunately, this transformation in the field of art, commonly referred to as consolidation, has weakened the support networks for complex aesthetic works. For some artists, this has opened up to more straightforward forms of business, such as designing apparel. Many small and medium-sized galleries have shuttered.

This rupture in the field reveals some of the codified aspects of the system of art. What may be perceived as a loop of network-specific gestures, language, and codes—such as the very invocation of the artist as radical agent—can be defined in operative terms: semantic style. Terry Young, CEO of Sparks & Honey, arrived at this idea through years of experience, but specifically through the firm’s recent work with Gerber, a heritage maker of baby food. The necessity to understand semantic style for Gerber’s market arose from, according to Young, the “challenge of connecting with millennial moms in their natural habitat, Instagram.” Via the analysis of syntax, vocabulary, and emoji use, a simple lexical hack was built for Gerber to produce impactful, relatable content. The corporate imperative here is clear: connect with the potential customer on an emotional level so as to ensure the brand’s continued success in their specific market. The apparent simplicity of using image and text to create points of connection raises a larger set of questions. At what point do these language hacks and the corporate algorithms that govern social media feel totalizing or even fascist? On a warmer note, how do individual users engage with networks to produce ties that bind? What are those emotional units that draw millennial moms to a storied brand? Within this dynamic yet discrete model of information input and goods-and service-based output, the artist is no longer a radical agent. For someone like Young, artists, even well-known ones, are simply more data points to be fed to Q.

Erika Vogt, Action Unrestricted, 2005. Performance documentation, 45 min., 16mm film, altered film projector, baseboard. Courtesy of the artist and Overduin & Co. Photo: James Welling.

If a filmstrip passes through one’s hand, it must end up somewhere—perhaps in an unruly pile at one’s feet. In these tangles of proverbial film, there is actually a complex, multi-dimensional, individuated potentiality. Each frame is connected to a distinct author and their network, and is ordered by the algorithm within a series of other posts. Further, each frame is part of a larger montage of social networks, which recombine to create a new, distinct form for each user. In short, within every media feed are systems waiting to be formed—and with them, the great promise of any new network: a new family. Each individualized topology of frames, in all their complexity, waits in the space of reception for an Akira-like growth into the field of production. This is the monster of totalization. This is how worlds are made.

As producers of our own worlds, therefore, conscripted to the content industrial complex and rendered visionless by this engrossing process, we must ask a few ontological questions. Who am I? Where do I stand? And what do I stand on/in? To locate oneself in this emerging field of production, it becomes necessary to work through one’s own constellation of social relations. This social cosmology, toxic and harmonious, is the queen bee of production (to paraphrase Bourdieu) within the alienation of network culture. Here, other questions arise not dissimilar to those Sparks & Honey asks on Gerber’s behalf. What brings us together? What binds us? We each navigate complex social topologies, albeit with varying degrees of critical reflection. Some of us even purport to believe that the values of the heart override those of social capital. Shannon’s model raises still more questions: should communicative redundancy be embraced by those engaged in the fine arts? Does this redundancy bring us together, or is it divisive? Are the emotional units that bond Gerber moms to the brand a result of sequencing and bundling sent messages, in addition to the employment of Young’s idea of semantic style? Or is the specificity of what is not redundant separable from its repetitive functioning within a network? Finally, we must total the answers to the above and additionally ask: can the ties that bind us together depict the shape of my own network? Is my habitus the sum of the noise, repetition, and specificity of my network?

In the “worlding” model of understanding the ocean of images, social networks are understood more like subcultures: everyone from trust fund moms in Silverlake to underground club promoters in the garment district produce and consume a world of imagery that they both define and are defined by. Decades back, subculture was tied to a pursuit of authenticity. Now the question of authenticity has been replaced by that of efficacy. How effective is your image as a tool of connectedness? How sticky are you socially? (And what exactly does efficiency mean during this tumultuous technological shift?) Within such an enumerated paradigm, advertising, with its ongoing quest to produce a network (or a consuming [and consumable] demographic), is a key strain of visual culture to consider. After all, advertising is a profoundly literary, spatial, seductive, tantalizing, palpable form of social construction. When good, it produces more than a mirror of ourselves. It reveals neighborhoods, small cities, or even exotic islands made up of the kind of people we want to be with, what we want, and who we wish we could be. What more does a social animal dream of?

John Knoll, Jennifer in Paradise, 1987.

Advertising is desire minus reality. Even as mass technology colonizes our minds’ eyes with images, the human drive to narrate is coupled with our own addiction to the promise of new systems of everyday life—new relationships—be they romantic or familial. Here, the discursive networks that are enabled through technology must circle back to the human ability to discern the inner sensibilities of one another. This is work well beyond the scope of Q. As governments direct populations to seethe against their own countrymen, and while us “good” citizens on the left believe in our own righteousness, we must not forget that the ability to ascertain another’s character does determine destiny. The continued perceptibility of one’s heart by another is reason to interrogate and model alternative potentials in technological communication amidst the rise of corporate-driven artificial intelligence. The approaching singularity is not a reason to let our blood run cold.

Lindsay August-Salazar, An Alphabet Expanded, 2019. Courtesy the artist and Stene Projects, Stockholm. Photo: Carter Mull.

Seeking points where social groups are entangled with and shaped by imagery led me to Sparks & Honey. Yet we all know that what a firm like this offers is something less than redemptive. While Gerber moms may appreciate the chance to double down on the love they have for their child by purchasing the brand’s wholesome-seeming product, a quantifying system like Q has yet to figure out how to truly improve a social sphere. We all want those exotic islands of sociality and love. Yet both the traditional machinations of the culture industry and a contemporary machine like Q can only produce further alienation, separating us from one another and from ourselves. What is needed is a platform (both a social network and a logic of distribution) that archives and produces an allegory of the loss, transformation, and redemption of those units that create connection. Analysis and experimentation within social platforms will make clear the quantity, sequence, duration, redundancy, and specificity of messages to be sent within a system. What remains a mystery within this pressurized moment of network-centric self-determination is whether the limitation of the data we have, despite its vastness, will force individual users to move beyond their own habitus. (Does the complexity of network culture produce comparisons to the spiritual idea of the universe?) New platforms must be forged by all involved. Let us hope we produce idealistic islands of antagonistic and harmonious democracy, modeling alternatives to the totalizing dictations of the algorithms of social software.

Alex Klein, Amour, 2007. C-print, 16 x 20 in. Courtesy of the artist and Grice Bench, Los Angeles. Photo: Alex Klein.

Do places like this spring from the mystery of creation, or are there already available models for such work? As we live through complex structural transformations, as we work daily to feed the artificial intelligence that seemingly depletes our humanity, let us not forget the stakes placed on the algorithmic organization of images. The “pink spaces” generated by Viola and her colleagues are pliable windows of opportunity for different responses to the logic of cybernetics. We are not numb creatures. In fact, the entanglement of networks and swarm of images is a tidal wave of complex affects specific to those social formations. While defined groups do tend to behave in terms of coded gestures specific to their network, the question is not so much an analysis of such, but instead to look to what brings us together. Love seemingly develops at an inverse rate to the exponential growth of data. Once considered infinite, love is now a precious resource. As its scarcity grows, platforms to allegorize this dynamic are needed for this process of loss, not in homage to the heart’s obsolescence but to let the lexical function of aesthetics preserve and record this transformation, to be recovered from the bottom of the ocean by forms of future life. Let us not forget what the heart produces. x

Carter Mull is an artist based in Los Angeles. His practice treats the boundaries around segments of culture like parts of a montage, to be at times delineated, and at other times emboldened through synthesis.