A mantlepiece, a mirror, a cabinet window, and a crucifix face inward from the four walls of a small room. Wax dissolved into soap and poured into a cavity solidifies with a skinlike surface. A translucent slab melts against the surface of a mirror. Bri Williams’s saturated, embedded objects float like specters. Artifacts of family history, they surface together as if in rebirth through progressions of casting and carving. Williams spoke with Laura Brown on the occasion of her exhibition Sebben Crudele, on view at Queer Thoughts from January 30–March 21, 2020.

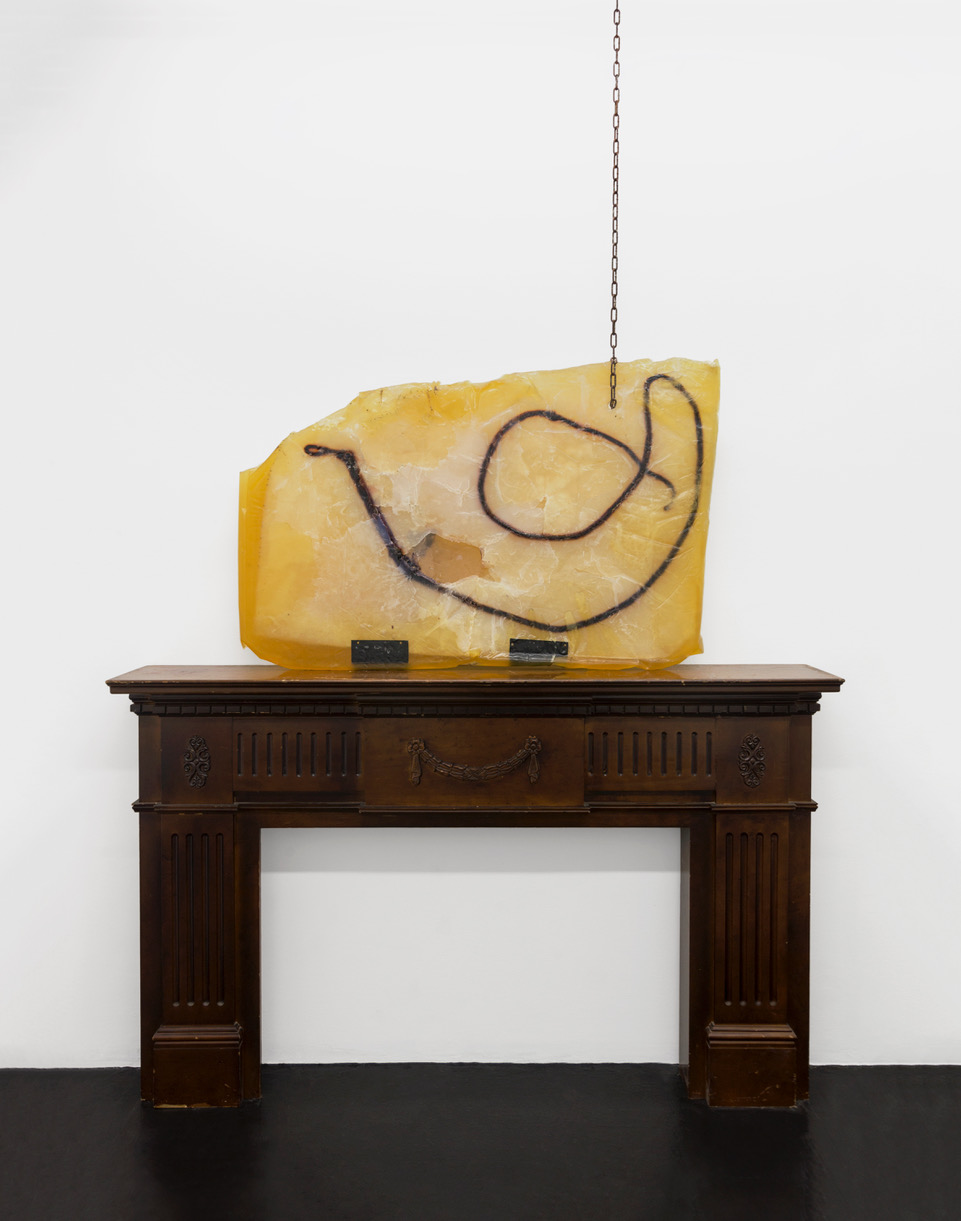

Bri Williams, Forward Hand Crack, 2019. Soap, whip, rubber, metal brackets, mantel, chain, 128 x 71.5 x 12 in. Courtesy of the artist and Queer Thoughts, New York.

LAURA BROWN: The arrangement of objects in this room recalls the inside of a home.

BRI WILLIAMS: I actually wanted to put wallpaper onto one of the walls. I live in my aunt’s house in Ladera Heights. It would have been the wallpaper that she has in my room. Her house is from the 1970s and she’s never remodeled it. It’s very eerie.

LB: The wallpaper didn’t work out?

BW: No. I think the mantel does enough. This home setting turns it into more of an Exorcist-like scene. I watch a lot of horror movies and ’50s, ’60s, and ’70s films.

LB: The objects do seem haunted. Could you tell me about the mantel with the whip in Forward Hand Crack (2019)?

BW: The whip is in the loop formation that must happen in the air in order to produce a forward hand crack. When you crack a whip, it causes a small sonic boom. The end travels faster than the speed of sound. I was interested in this, as well as the historical but also sexual connotations that come with it. I like how the brown dye from the whip bleeds out into the soap it’s embedded in, in this constant state of deterioration. It kind of freezes the demon in a moment. I do want things to be haunting. It becomes a ghost, but the body is still there.

Bri Williams, For the love of, 2020. Soap, wax, crucifix, silicone, 22.5 x 13.25 x 8 in. Courtesy of the artist and Queer Thoughts, New York.

LB: What is the process of finding these objects? Is it a generic mirror, or a specific mirror?

BW: I often source things from home, usually historical family objects. I do like for objects to be more personally related to me or my past. I’m finding a way to portray my family history that is contemporary but that also encapsulates all of this history. The first time I put a mirror shard in soap I noticed its strange reflection. You’re seeing yourself, the outline of your body, but you can’t look yourself in the eye. You become a ghost of yourself.

LB: If you’re not standing directly in front of it, the mirror is facing the crucifix work. What is the significance of this symbol to you?

BW: I have a strange relationship with religion. My mother’s grandfather was an Episcopal bishop. And on my father’s side, his grandmother’s husband was a Baptist minister. I used to go to church almost every Sunday when I was younger, and was confirmed when I was 15. But I honestly believed more in aliens than in Christianity. When I was about twelve years old, I was sitting in the church parking lot, saying, “I don’t want to go, I’m not moving from this car.” My dad stayed in the car with me. He told me the story of Cain and Abel. To cut the story short: God demands a sacrifice. Abel is the good brother who wants to sacrifice their best lamb, and Cain is the bad brother who wants to sacrifice some cheap hay. Cain’s hay won’t burn, but Abel’s lamb burns fast. Cain gets jealous of Abel and kills him. And when God asks Cain where his brother is, Cain responds with the famous line, “Am I my brother’s keeper?” My dad said that when they used to tell this story in Louisiana, where he grew up, they would say that Abel was white and Cain was black, that this Bible story was used as a kind of propaganda to further instill white hatred toward black people. He was like, “Listen, I didn’t like to go to church either, but make your mother happy and get inside.” I’ve never forgotten him telling me this.

For the crucifix piece, I wanted to embed the cross part in wax and have the body of Jesus sitting on the wax’s surface. Erasing the cross, just having the body revealed on top, is speaking to the pain instead of the actual symbol of religion. I’m always trying to communicate pain in my work. I think this has a lot to do with the reasons why certain people hate other groups of people. They can never feel the pain that another person has felt in their life.

Bri Williams, Closer II, 2020. Mirror, soap, 50.5 x 22.5 x 2 in. Installation view, Sebben Crudele, Queer Thoughts, New York, January 30–March 21, 2020. Courtesy of the artist and Queer Thoughts, New York.

LB: The title of the show, Sebben Crudele, is the title of a song you learned in church, right?

BW: I was in church choir when I was about nine. At the time I thought that this song was a church song, but my choir teacher was more into opera music, and when I found the old sheet music in the back of my closet, I looked it up. It’s an opera song about love and devotion to somebody that causes you pain. I thought a lot about how sometimes this instance of hurting and longing becomes a big part of the lust or the love. At the same time, this song has a connection to religion and the idea of the sacrifice of soul and body.

LB: You also reference Toni Morrison’s first novel, The Bluest Eye (1970). Were you reading that at the time?

BW: I was. Speaking of communicating the pain of being a black woman, she’s somebody who’s really good at this. Reading it put me back into those places of trauma, while also verifying that certain instances that I’ve dealt with were real, that they’ve affected me. I’m not just being paranoid when people look at, talk to, and touch me a certain way. She puts the reader in that position. To some, it is painful to read and to understand that this is our truth. When many people around you every day treat you like you’re ugly in their eyes, you start to believe it. She speaks to this experience in relation to young black girls. It’s something that you have to look in the face, to realize what you’re projecting upon yourself as well as what everybody else is projecting onto you.

Bri Williams, Jezebel, 2020. Soap, taxidermy sparrow, wax, 6 x 8 x 8 in. Courtesy of the artist and Queer Thoughts, New York.

LB: In the office a taxidermy sparrow emerges from a brilliant pink encasement. Is there a story behind this bird? Its title, Jezebel (2020), is allegorical.

BW: It’s a California house sparrow. My parents’ house in Long Beach had an adobe clay-style rooftop. Every spring these birds would have their babies in the crevices. Sometimes the eggs or the baby birds would fall from the rooftop. I’d go outside and there would be a dead or dying baby bird on the ground. I would pick it up and put it on a wall and within ten minutes that baby bird would be gone. So, I chose this specific bird, freezing it in time and in motion. This piece is part of a larger series, Scars that heel and don’t fester (2020). They were made to commemorate those birds, but afterward I began to relate them to iconic female roles in 1950s movies, such as Carmen Jones (1954, played by Dorothy Dandridge), Anna Lucasta (1958, played by Eartha Kitt), and Jezebel (1938, played by Bette Davis).

For this specific bird, I mixed wax into the soap and it turned opaque, so I needed to carve it out. My friend Emily Barker helped me carve out the majority, all the way down to the bird. Then I retrieved the detail, trying not to damage the feathers. It acts as a relic or a talisman, almost.

LB: The works also act very much like portals, suspended upright.

BW: I wanted them standing up straight, showing themselves to people directly: This is who I am. Not leaning heavy against the wall. I think these objects have their own personalities, intentions, and stories. I want them to be something like a punch in the face. x

Bri Williams lives and works in Los Angeles. Solo exhibitions include Interface, Oakland; Pina, Vienna (forthcoming); and a two-person exhibition with Diamond Stingily at Ramiken, Los Angeles. Williams’s work has been presented in group exhibitions at Karma International, Los Angeles; Diane Rosenstein, Los Angeles; and Queer Thoughts, New York, among others.

Laura Brown is a writer, curator, and editor living in New York.