The Dash column explores art and its social contexts. The dash separates and the dash joins, it pauses and it moves along. Here, Rahel Aima peels back the digital plywood from American Artist’s Looted, a project commissioned by the Whitney Museum of American Art that has boarded up their website twice a day since July.

American Artist, Looted, 2020. Online artwork for the Sunrise/Sunset series on artport, whitney.org. Screenshot. Courtesy of the artist and the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York.

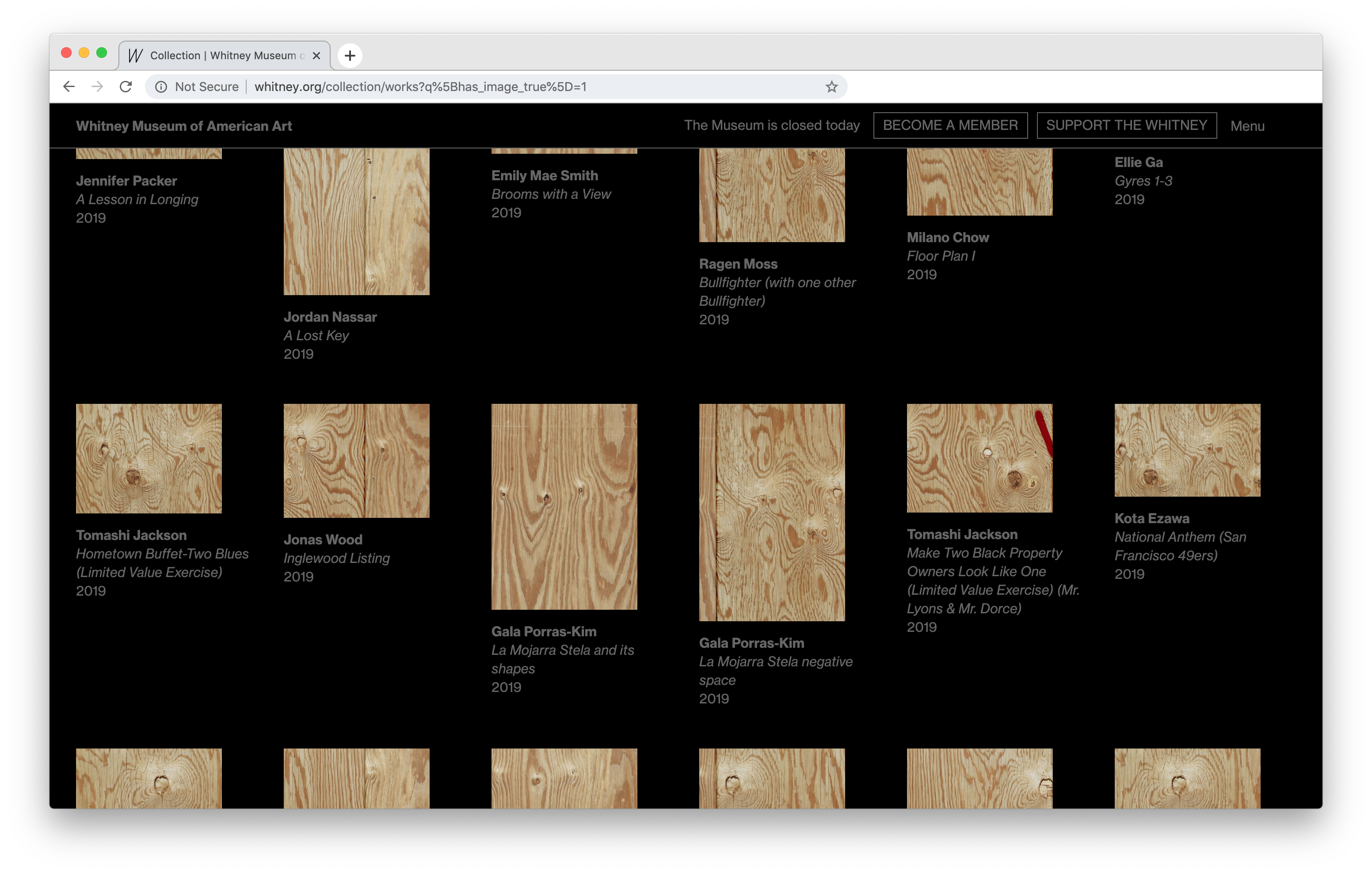

As protests against police brutality intensified across the country last summer, Gucci, Sweetgreen, and the Whitney Museum of American Art boarded up their windows. At precisely 8:21 p.m. on July 21, 2020, as the sun dipped into the Hudson, the Whitney Museum’s website went dark too. All text, including a large header proclaiming that the institution stood with Black communities, was recast in gray against a black background, hitting the dimmer switch on the museum’s curatorial voice. Meanwhile, all images of art on the Whitney website were replaced with images of plywood. It happened again at sunrise the next day, and again at sunset, and has continued to happen twice a day since then. Lest you worry that the rioting rabble has breached the walls of the institution, a corner popup informs you that this is Looted (2020), a work by American Artist, and that it will be over in thirty seconds.

Redaction functions in American Artist’s practice not as resistance so much as a protective gesture. It is seen most overtly in their concept of dignity images, the personal snapshots that are withheld from circulation on social media—as they write, “whether out of shame, security concerns, sentimentality, financial viability, or convenience,” and thus “may be put to use in recovering one’s dignity, or political autonomy, online.” In the yearlong online performance Refusal (2015–16), the artist accomplished redaction by replacing all images of themselves on their own Facebook with a no-signal blue rectangle. Importantly, these rectangles are digital placeholders for unredacted images that are printed out and collected in a unique photo album, viewable for the duration of the project by appointment only. With Looted, the redaction instead mimics the way that a museum takes artworks out of circulation, into storage, only very rarely deaccessioning them. It also invokes, in admittedly museum-sanctioned plywood, artist Parker Bright’s 2017 protest of Dana Schutz’s Emmet Till painting in which he stood in front of the work wearing a T-shirt that read “Black Death Spectacle,” blocking it from view. (Less than a year later, a French-Algerian artist would appropriate an image of Bright’s protest, which resulted in the latter flying to Paris to repeat his performance.) In all instances, the redaction’s message is the same: these images are not for you to consume.

Workers boarding up the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, on June 3, 2020. Courtesy of Dreamstime and Chris Cintron. Photo: Chris Cintron.

We might wonder what, precisely, is being looted and from whom (and with whose money). That August, a scant month after Looted began, the Whitney canceled a show of printed matter and artwork purchased—at a pittance relative to artists’ usual prices—at COVID-19 and Black Lives Matter benefit sales. Despite the ongoing debate around the restitution of stolen artworks, museum acquisition practices continue to be colonial and exploitative. It’s hard not to see in American Artist’s project an extended visual pun about the museum’s board of trustees. One wonders whether the plywood is truly there to protect the artwork from the specter of future looters or whether, as the past-tense title suggests, it refers to looting that has already occurred—of other people’s cultural patrimony perhaps, or even workers’ livelihoods, with museums’ collective rush to fire or furlough primarily BIPOC lower-wage workers even as they hire union-busting law firms.

Looted is part of the Whitney’s Sunrise/Sunset series of digital works that mark New York City sunrises and sunsets, interrupting the website every day. Past projects have variously turned whitney.org into a number of sky- and sunset-themed works and a watery ecosystem for flamingos and penguins. “This form of engagement captures the core of artistic practice on the Internet, the intervention in existing online spaces,” its landing page explains. There is no small irony in the name the museum gives its online gallery, artport. Launched in 2011, the project seems to hearken back to the days of website-as-portal, but also recalls the term for the art-specific tax haven-cum-storage sites, or freeports, found at financial hubs like Geneva and Hong Kong. More than atmospheric set-dressing, Looted captures the real core of artistic practice on the internet: to turn screens into plate glass windows, thereby to sell things. What is an online gallery but a glorified digital storefront?

We can also think of redaction as a form of encryption that lays bare the fantasy of the digital exhibition and access, the assumption that putting something online means it is accessible to a vaguely articulated everyone. The webstore is always open for business but the digital exhibition, trying its best to mimic physical ones, usually runs for a limited time, even if it is also archived in some way. Why the artificial scarcity? I wonder who goes to these things—whether the occasional museum-going public does in fact delight in being able to zoom in on paintings from the comfort of their couch. Restricting access in this way has more than a whiff of the extended colonialist insult of so-called “digital repatriation,” a phenomenon where museums propose digital surrogates in lieu of actual artifacts being physically restored to their originating cultures. This move couples a certain paternalism with an assumption that the repatriation of artifacts is about academic study—for which hi-res digital scans should suffice—and not about their cultural or spiritual import.

Jesse Kreuzer, Lafayette Square, 2020. Latex acrylic and crayon on plywood, 31 x 10 ft. Mural at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Jesse Kreuzer.

One wonders, too, if it’s the logical extension of the Contemporary Art Selfie effect in which works seem to be made to excite as an installation view JPEG but are sorely disappointing in person. Or is this post-internet art—which emphasized the dematerialized artwork in its time but is now seen as a little bit corny, the art analogue to third-wave ska—having a last laugh? Consider three online shows-as-artworks from 2010 in which images of works from the post-internet set were photoshopped onto images of empty gallery spaces. The group shows Mirrors and An Immaterial Survey of Our Peers, both curated by Brad Troemel, used Reference Gallery’s physical space in Richmond, Virginia, and the galleries of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, respectively. In October of the same year, Timur Si-Quin presented Chrystal Gallery Exhibition One, which did the same thing but with 3D-rendered works in a constructed environment. The results are all but indistinguishable from the online viewing rooms of today.

It is worth differentiating net-art, online-only videos, and other works made for the internet from the online viewing rooms that have proliferated during the pandemic. (The former media, to be clear, are generally not good but usually better adapted to the digital environment than paintings on canvas, whose qualities and sense of presence are generally lost when compressed into JPEG form.) And it has been interesting to see the additional content that some galleries and institutions try to provide, from curatorial walkthroughs and live streams of earnest talking heads—when else have curators gotten so much visibility?—to 3D-scanned models of galleries that you can move through like a streetcar named Google. But right now, like the Geocities and Angelfire websites of yore, or plywood-fenced building sites the country over, they remain permanently under construction.

As for the Whitney, the boarded-up physical building soon hosted wave after wave of graffiti, from “FTP” and “BLM” scrawls to a WPA-style mural depicting police brutality to a portrait of an Elmo on fire. On a closed city storefront, as layers of tags accrete and weather discolors the wood grain, such a scene would invoke something closer to urban blight. But the thing that blights the Whitney is the rotten philanthropy at its heart; online, the plywood remains pristine. x

Rahel Aima is a writer based in Dubai. She is an associate editor at Momus and editor of BXD: The Postwestern Review.