For the eXhibitions column, Matt Siegle and Kent Monkman discuss Kent Monkman: The Great Mystery (on view April 8–December 16, 2023 at the Hood Museum at Dartmouth), in which Monkman painted their avatar Miss Chief into riffs of modernist masterpieces in the Hood’s collection and hung them cheek to cheek.

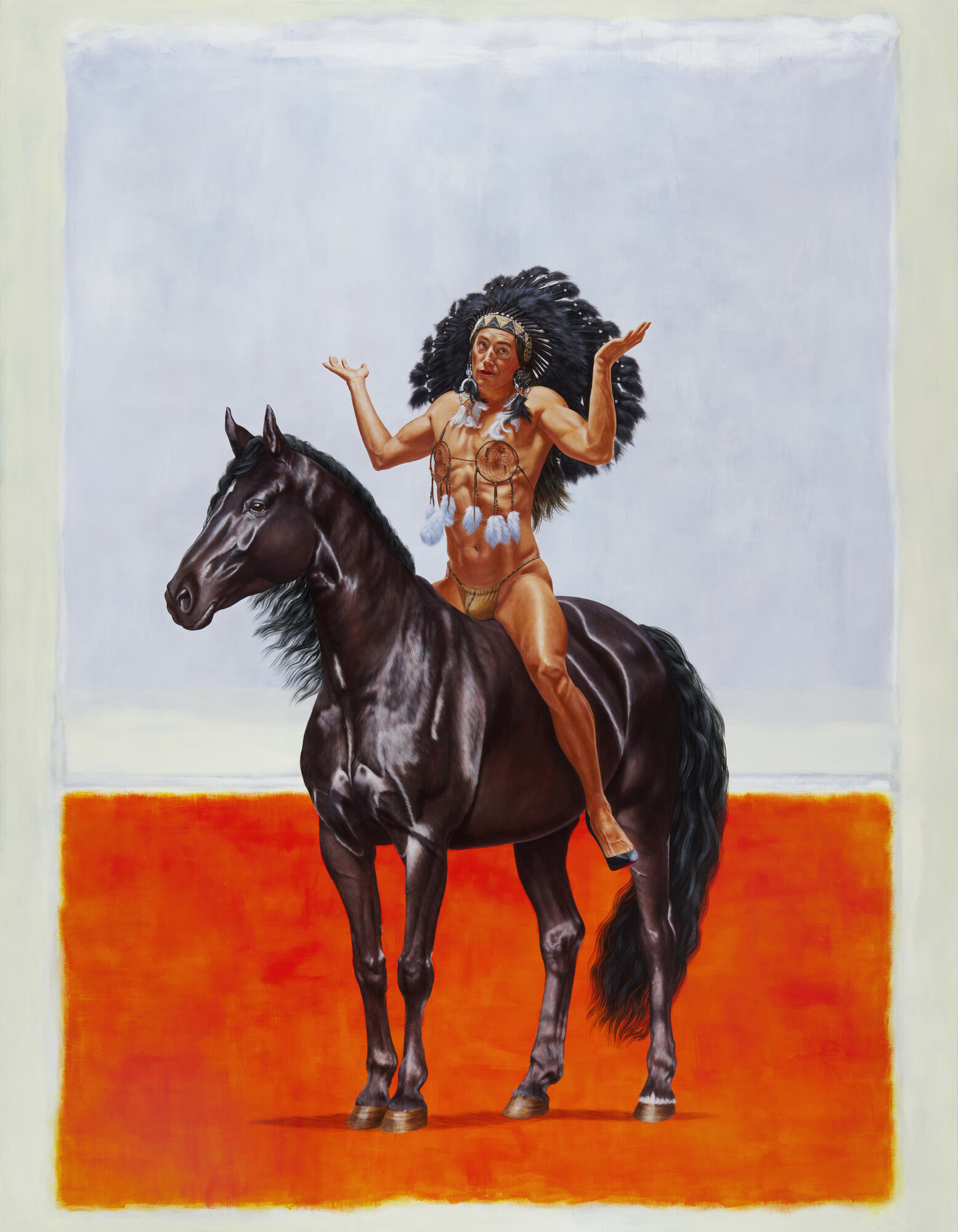

Kent Monkman, The Great Mystery, 2023. Acrylic on canvas, 117 ½ × 91 ½ in. Courtesy of the artist.

Matt Siegle: You were invited to come to the Hood and create a project working with the collection. Typically, you make highly representational paintings. How did you end up at abstraction?

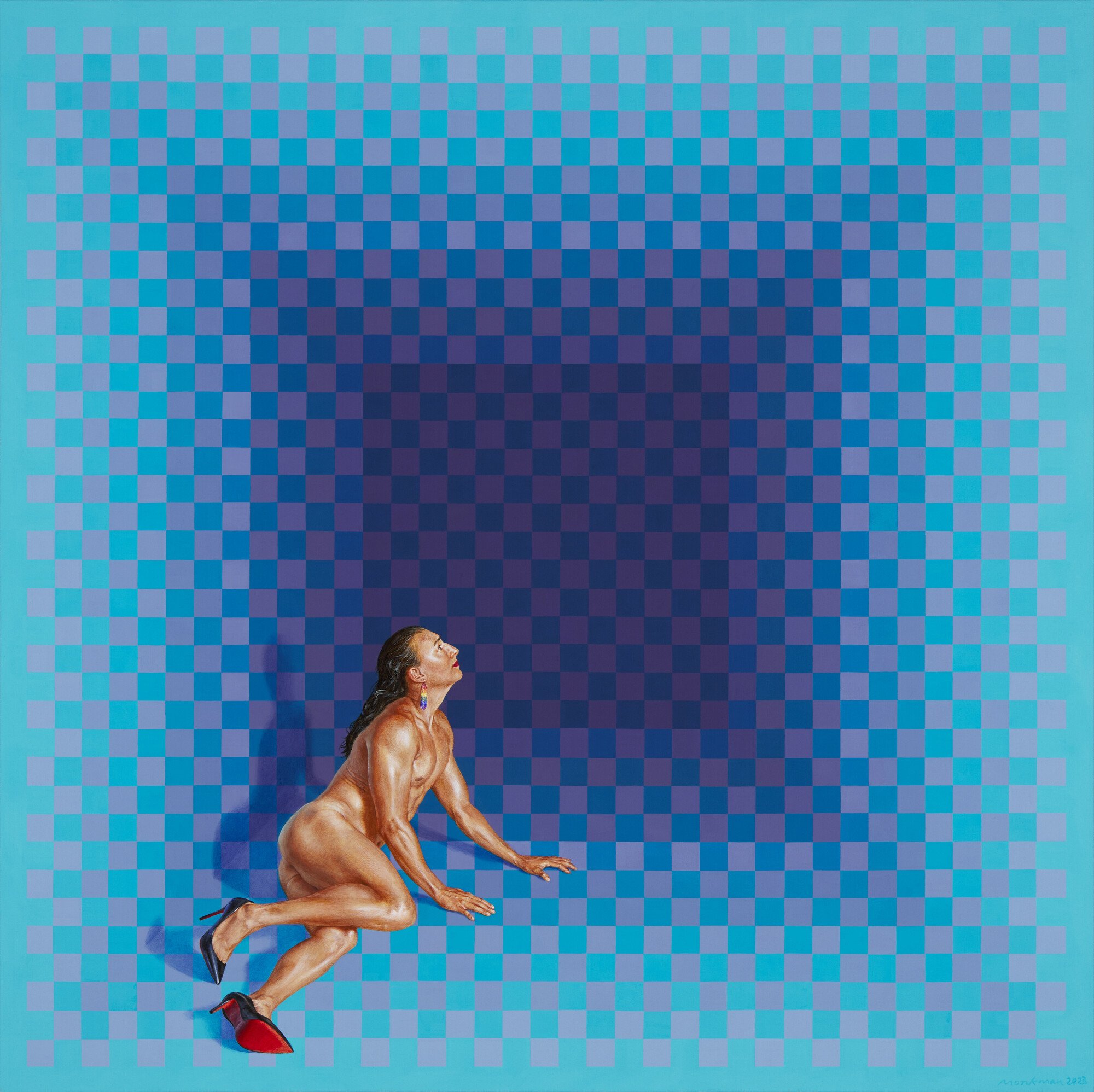

Kent Monkman: To me, these paintings represent Western art’s logical journey towards finding spiritual transcendence in minimal art, understanding that a painting can be a void or empty vessel. It can be a receptacle of your own projections, your emotional state, your psychological state, your spiritual state. That’s what I was pursuing in my own practice, trying to describe mamahtâwisiwin, part of the Cree worldview, which is about tapping into a spiritual interconnectedness of unknowingness, and being comfortable with not knowing. Because we all want to have a definition, or to be comfortable. But being an artist, we are so often in that state of being lost.

One of my dear friends—he’s no longer on this earth—was a Catholic priest, among other things, but kind of a rebel priest. The original meaning of the word catholica, the way he described it to me, was about being in between. He equated it to that the highest form of his faith was being lost. To be in a state of unknowingness as the kind of pinnacle, that place where you are without ego, you are sort of humbled.

Kent Monkman: The Great Mystery. The Hood Museum, Dartmouth, New Hampshire, April 8–December 16, 2023. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist and the Hood Museum. Photo: Rob Strong.

Kent Monkman: The Great Mystery. The Hood Museum, Dartmouth, New Hampshire, April 8–December 16, 2023. Installation view. Courtesy of the artist and the Hood Museum. Photo: Rob Strong.

MS: You’ve given yourself a difficult problem, because the sublime, which is what some people might talk about with Rothko, is ineffable. People turn to expression in visual aesthetics because they don’t feel that words can justify or encompass these ideas. In hearing you talk, you’re wanting to open that conversation, but with an urgency about the problems of living with a colonial legacy, whether it’s of your sexuality or your racial background. I don’t envy you that problem. But that’s also what I admire about these works. I think your alter ego Miss Chief is this portal, if you will, that allows people to enter that conversation. But what is so pointed about your ideas and then approaching high modernist abstraction is that the unknowingness of that generation seems very internal.

KM: It’s also connected to the ego. It was a very macho movement. Macho white dudes flexing their painterly muscles.

MS: To me, that stands in contrast to the idea of an interconnected unknowing. I could start to see your work as a bit of a critique that way. Because you’re suggesting a more accessible way into what for others was a closed conversation.

KM: That’s where her name, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, came from. She basically puts herself into her work instead of flexing the muscle, necessarily, with the obvious drip or splash or wiggle. And so it removes that self-conscious idea of the ego, gets the elephant out of the room. Like, okay! Yes, the ego of the artist is here, front and center. And we have a laugh about that.

My critique is so much about the museum as this place that upholds this voice of authority. It’s how culture is translated and shared and taught. So much of my work is about interrupting how museums function and the stories that they tell, amplifying Indigenous knowledge so that people understand there is this whole universe out there that the settlers of this continent haven’t bothered to pay attention to.

Kent Monkman, Muted Cell (Blue Light), 2023. Acrylic on canvas, 40 x 40 in. Courtesy of the artist.

MS: I’d like to talk about the origins of Miss Chief.

KM: She appeared in the paintings as a way to reverse the gaze. I was looking at the work of George Catlin and others, who sometimes painted themselves into their work. It was a way of showing off, like, Hey, we went to meet some real Indians, and here I am painting some Indians. Those images were so successful in disseminating very limited understandings and ideas, which was useful at the time, because Native American people were supposed to be out of the way by then, or if they weren’t, we needed to get them out of the way. They sold an idea of something from the past that was romantically beautiful in its vanishing state… Not living in the present, not being innovative and moving forward into the future. But then the images became so ubiquitous and shaped society’s ideas about who Indigenous people were to a point where 150 years later, it’s still the understanding. And again, museums became supporters of those views. Until very recently.

MS: And some of the other inspiration points for Miss Chief?

KM: First of all, I wanted to communicate Indigenous ways of thinking around gender and sexuality, to undo some of this colonial thinking that came from church and state, defining very binary ideas about male and female. And exploding that, I created a character that was comfortable in her fluidity, in a state of being male and female, drawing on Indigenous cultures. In Cree there’s no he/she pronouns, so fluent Cree speakers mix up he and she all the time because it doesn’t matter.

MS: And if I understand correctly, two-spirit persons were historically accepted in their fluidity.

KM: Absolutely. And I wanted her to be the author, the voice of authority, to offer her perspective and balance these other perspectives, specifically throughout art history. I inserted her into these 19th century paintings, and she emerged as this legendary being that could exist and function in different time periods. As a witness. But how is it that she doesn’t intervene and she can’t intervene? Because that would change the course of history. I’m not gonna rewrite history, I’m just looking at it from a different point of view. And in writing her memoir, we had to ask those deep questions about who she is, and what’s her purpose.

Kent Monkman, Ghostflower, 1997–2022. Acrylic on canvas, 60 x 96 in. Courtesy of the artist.

MS: Is Miss Chief you?

KM: Well… Yes and no. Miss Chief is a character that I created that is gender fluid, who is between he and she. But there’s a lot of me in Miss Chief, obviously.

MS: It’s fluid, maybe.

Miss Chief in these paintings is the accessibility point. And I think some of that comes because she’s pretty fabulous! In Study for Lit Skin in a Limo (2022), the red boots go up mid-thigh, there’s a little bit of sparkle on the thong, and the—what some people might call dream catchers—as a bra. It’s pop. It’s also somewhat camp. In your talk yesterday at the Hood, you mentioned Bob Mackie and his costumes, this grand celebration of the elaborate. And that combined with Susan Sontag’s idea about camp and sexuality sort of going against the grain a little bit, while being over the top.

Kent Monkman, Study for Lit Skin in a Limo, 2022. Acrylic on canvas, 30 x 30 in. Courtesy of the artist.

KM: There’s a component of camp, but I don’t want that to overtake the work. It’s all part of a larger strategy to seduce the viewer, to pull them in, because there are many levels in painting. And so I also like to make surfaces that… you want to lick. And again, that goes back to painting. Look at the surface of that Fritz Scholder face. That looks like a face of someone who’s been beaten up and thrown in the back of a police car. It looks like that person had a rough night. There’s a kind of quality to that skin that’s so visceral and raw. And then here’s Miss Chief’s skin, it’s buff and glossy.

MS: Like it’s oiled, basically.

KM: And then the whole interior of the limousine, and the symmetry of the composition, it starts to feel like the Beckman. This square, this illusion of a three-dimensional space, a box within a box, the illusion of depth created just with color. This Beckman is a mind-blowing painting! You just want to drift into it. And that’s pure paint, and it gets me so excited.

There’s something so different about photography and painting. Painting is lensed through these two lenses right here. [Pointing at eyeballs.] Painting literally goes through these two lenses, out this hand, and back through human lenses. That’s why I have so much belief in painting and in the power of painting. The humanity of it will always trump a photograph. As much as I love photography, nothing can replace that—well, I want say magic, but it’s more than that. It’s—

MS: Mamahtâwisiwin.

KM: Yeah! It’s about that interconnectedness and unknowingness, that frailty of the human hand and these incredible moments that just happen and are just out of your range of control. x

Kent Monkman is an interdisciplinary Cree visual artist. A member of Fisher River Cree Nation in Treaty 5 Territory (Manitoba), he lives and works in New York City and Toronto.

Matt Siegle is a mixed-media artist with an itinerant studio practice. He has exhibited throughout the United States and Europe. Siegle teaches sculpture and drawing at Dartmouth College, where he is also the Class of 1960 Curatorial Fellowship Advisor.