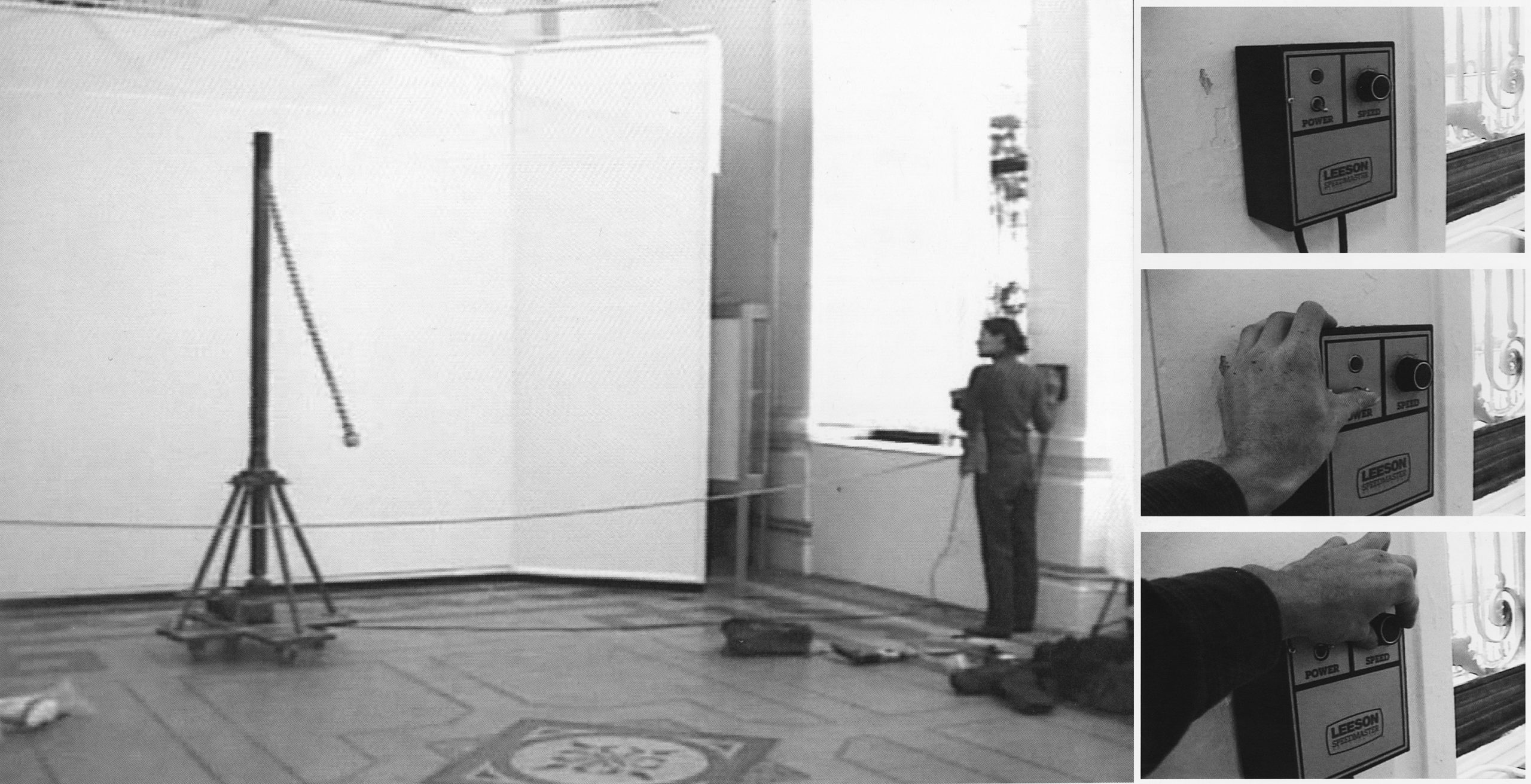

The Dispatches column delivers reports and diatribes from the front lines of contemporary art. Here, Chris Murtha considers that Liz Larner’s imposing Corner Basher, a machine seemingly born to destroy, might have a subtler purpose. Editor’s note: Larner requests that all documentation of the sculpture shows someone’s hands on its controls. The work appears in Larner’s retrospective, “Don’t put it back like it was,” on view at the Walker Art Center through September 4, 2022.

Liz Larner, Corner Basher, 1988. Steel, stainless steel, electric motor, and speed control, 10 ft. high. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

A fist-sized wrecking ball hangs by a chain from the central column of a motor-driven apparatus, itself chained into a corner. This is how many people, myself included, first encounter Liz Larner’s Corner Basher (1988): silent and inert, yet threatening. The pockmarked sheetrock and the debris accumulating on the floor alert the viewer to the machine’s violent potential. Switched on, the motor revs up and begins swinging the lump of metal, which lashes into the gallery walls, bouncing off one and careening against the other with increasing force until the piece is powered down.

Larner debuted this agent of demolition at the artist-founded Los Angeles Contemporary Exhibitions (LACE) in a 1988 group show of artists who, as the poster advertised, “bite the hand that feeds them.” While Corner Basher initially registers as an aggressive form of institutional critique—a response to the brash gallery-space interventions of Vito Acconci, Barry Le Va, and Chris Burden—such a framing ignores a crucial nuance of this sculpture: that it is audience-activated. A control box, situated at a safe distance, allows viewers to turn the motor on and off and vary its speed. Corner Basher is unable to conduct its perverse work without assistance from its spectators.

Liz Larner, Corner Basher, 1988. Steel, stainless steel, electric motor, and speed control, 10 ft. high. Installation view, Don’t put it back like it was, SculptureCenter, New York, January 20–March 28, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Cathy Carver.

Larner referred to the sculpture as a “personality test” in a 1990 interview, and later likened the experience of activating it to the freedom and responsibility associated with driving a car—a “potential killing machine.” When I interacted with the piece at SculptureCenter in New York, as part of Larner’s survey Don’t put it back like it was (currently at the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis), I became yet another participant in her ongoing social experiment. I flipped the switch and gradually increased the speed, cautioned by a gallery attendant to turn the dial slowly and not too high. The rising sense of shame I felt as the steel ball started raucously impacting the wall surprised me. Maybe it was embarrassment at having caused such a commotion in the otherwise hushed galleries, or the fact that I, having entered into a kind of performance with the sculpture, suddenly had an audience. I immediately wanted to turn it off. The aversion I felt clearly says more about me than Larner, or anyone else who activates the work, and my reaction was just one of many possibilities. Whether someone responds with bemused indifference, gleeful catharsis, or shame (as I did), they play a role in producing the final artwork: a collectively-enacted, site-specific “drawing” that turns a destructive force into something generative.

Rather than opposing the architecture of her institutional hosts, as Corner Basher might suggest, Larner has more often negotiated a tense counterpoise between her sculptures and their sites. The artist is especially fixated on corners, as evident in Too the Wall (1990), a delicate ribcage of spindly steel rods and jump rings that support swatches of untreated leather. Jewelry, piercing, and harness, the work fans out from the corner like a kinky cobweb. Its industrial counterpart, Wrapped Corner (1991), exemplifies the site-specific installations Larner produced with high-tension industrial chain in the early 1990s. The dozens of chains that bind one corner of the gallery are wound tight enough to form crisp parallel lines, but not enough to rip apart the wall.

Liz Larner, Corner Basher, 1988. Steel, stainless steel, electric motor, and speed control, 10 ft. high. Installation view, Don’t put it back like it was, Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, April 30–September 4, 2022. Courtesy of the artist and Regen Projects, Los Angeles. Photo: Eric Mueller.

Larner treats the space of presentation as an integral component of her artworks, and several sculptures span entire galleries. Bird in Space (1989), a soaring homage to Brancusi in nylon cord and silk thread, appears to take wing, arcing above gallery-goers’ heads and extending to the rafters. At the Walker, Head, Torso, Foot (1989) prohibits visitors from passing through a section of one gallery as it simultaneously signifies a figure. Each of the sculpture’s three woven cubes, tethered to the walls with knotted fabric, references a titular body part and hovers at the corresponding height. At SculptureCenter, Larner’s series of gold- and silver-plated chain mail sculptures, titled Guests (2004–5), inhabited various niches of the raw basement galleries—hiding under the stairs, emerging from a crevice, and draping over a pipe—drawing our attention to marginal spaces and the venue’s peculiarities, while reminding us that we, too, are guests.

Larner has likened sculpture to dance, since it requires viewers to move around objects—performing, in a sense, the art of looking. With some early installations of Corner Basher, she more explicitly antagonized viewers. Unleashing the apparatus from the wall, the artist enabled it to drift about, propelled by the ball’s impact and swing. In making space for itself, the machine not only threatened the institutional infrastructure but the audience as well. Lash Mat (1989), a strikingly different sculpture made only a year later, provokes a similar push and pull. Cascading down the wall to rest on the gallery floor, the ten-foot-tall leather scroll is coated with countless false eyelashes made from human hair. The inky black lashes ripple out from a central vortex, an eyelike formation that pulls viewers closer to its lush, unsettling surface.The sculpture’s punning title echoes the explicit violence of Corner Basher, but it is really the abject quality—and quantity—of the disembodied hairs that unnerves. Like a moth’s deceptive eyespot or an evil eye amulet, Lash Mat returns our gaze in a manner both alluring and repellent. As with so many of Larner’s objects, Corner Basher and Lash Mat refuse to be passive partners. X

Chris Murtha is a writer and curator based in Brooklyn, New York.