For the Dispatches column, Ezequiel Olvera reflects on the contemporary violence in MacArthur Park, the historic destabilization of Latin America by the United States, Eurocentrism, and Elaine Cameron-Weir’s Exploded View / Dressing for Windows at Hannah Hoffman Gallery in Los Angeles, on view November 12, 2022–January 14, 2023.*

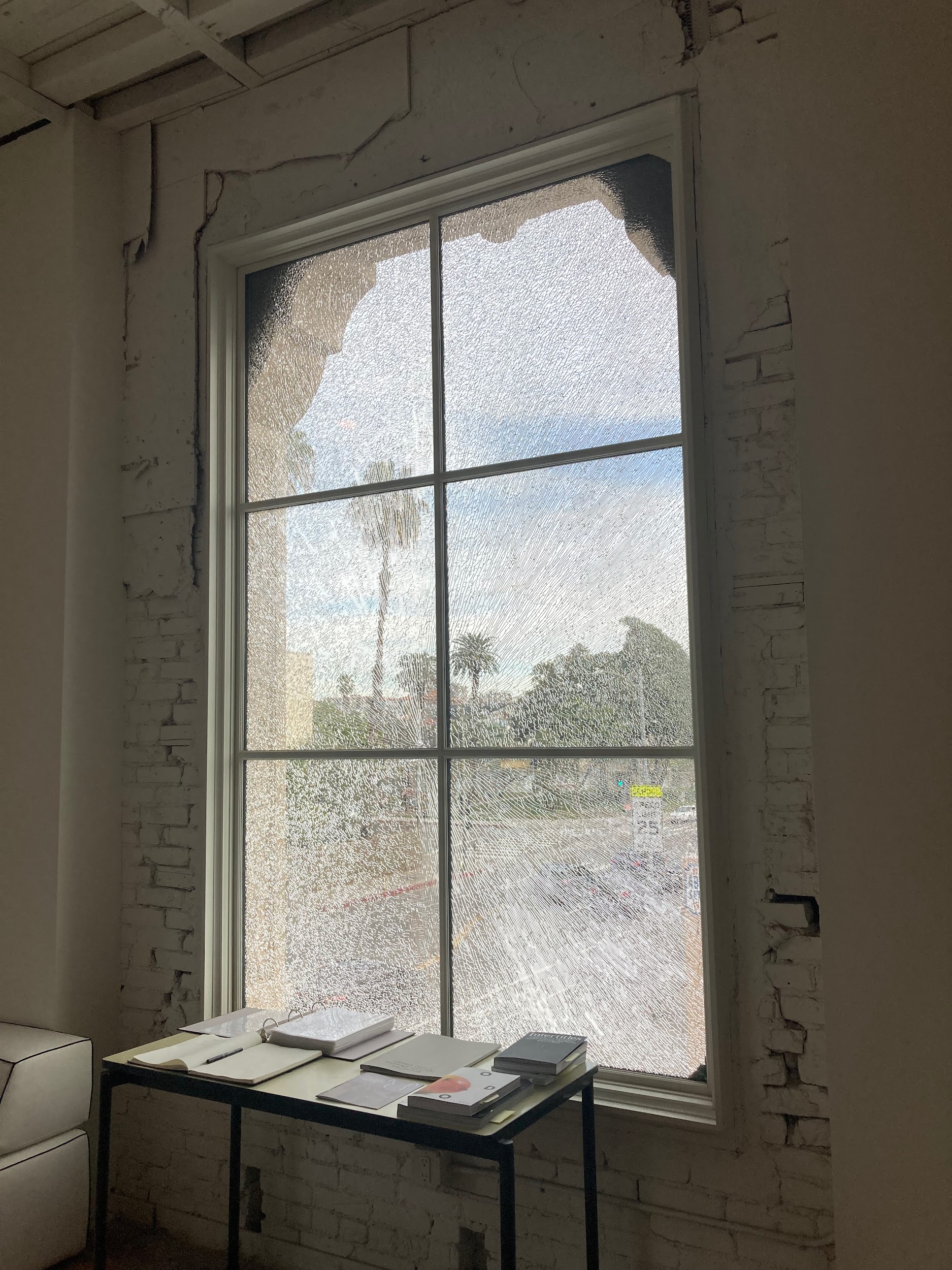

Shattered window at Hannah Hoffman Gallery, 2023. Photo: Ezequiel Olvera.

The day I visited Elaine Cameron-Weir’s exhibition Exploded View / Dressing for Windows at Hannah Hoffman, I noticed one of the gallery’s windows was shattered but intact. I imagined that a stray bullet from a gunman in MacArthur Park had fractured the glass like a spiderweb glistening in the sun. Through the brokenness, I saw the painting on the building next door: a dove emerging from a bible with the words “IGLESIA PENTOCOSTES” above it.

As I walked to the gallery, I was approached by a group of proselytizers. A woman veiled in white asked to pray over me. Soon I had the hands of six other church members on my shoulders. They repeated their hypnotic mantras, hoping that I would join them in their state, but the sparkle of their silver tooth replacements kept distracting me. So did the fact that their Catholicism was the product of colonial indoctrination forced on Indigenous peoples over centuries.

Once inside, I gazed at Cameron-Weir’s installations, wondering if she had set foot in the park. Although her work entangles religious symbolism, political manipulation, economic weaponry, and industrialism, MacArthur Park, a place formed by those forces, peering through the cracked window, could not have felt farther away.

Elaine Cameron-Weir, Exploded View / Dressing for Windows. Installation view, Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles, November 12, 2022–January 14, 2023. Courtesy of the artist and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff Mclane.

MacArthur Park Lake is a scarred place of exquisite beauty where massive carp swim below floating Canadian geese and bobbing ducks. Chattering clans of California seagulls swarm over fishermen, Guatemalteco street vendors, soccer players, and evangelists shouting from karaoke machines with echo effects.

Despite the park’s charm, it has known violence—murder, homelessness, and prostitution multiplied well into the nineties. When the lake was partially drained in 1973, then pumped dry five years later, the exposed detritus gave John Woods, a former aerospace worker, the artistic epiphany to use the material for assemblages and sculptures: “hundreds of watches lost overboard by row-boaters, thousands of corroded coins and trolley tokens, rusty tools, toys of every description, countless encrusted guns and knives.”

Major renovations in 2021 and homeless assistance programs, like Project Roomkey, have started to bring peace and stability and uplift the community, but the wounds of the past linger. For the past five years, MS-13 has claimed the area as its barrio and has threatened and assaulted transients in the community, especially transgender sex workers. In the end, the contemporary violence of the clika is the vestige of the United States’ continuous military and economic destabilization of Latin America, including the CIA’s alleged role in the distribution of crack cocaine to Black and brown communities. Our democratic colonial empire has funded brutal violence in the region for over 200 years, from the Banana Wars and El Salvadoran death squads to the 1954 Guatemalan coup d’état and the Nicaraguan Contras. Ernesto Deras, a founding member of MS-13, was trained by the Green Berets in Panama at the Western Hemisphere Institute for Security Cooperation, the military school for U.S.-backed juntas. MacArthur Park Lake is a 37-pound carp with a sunken gun sploshing around in its belly.

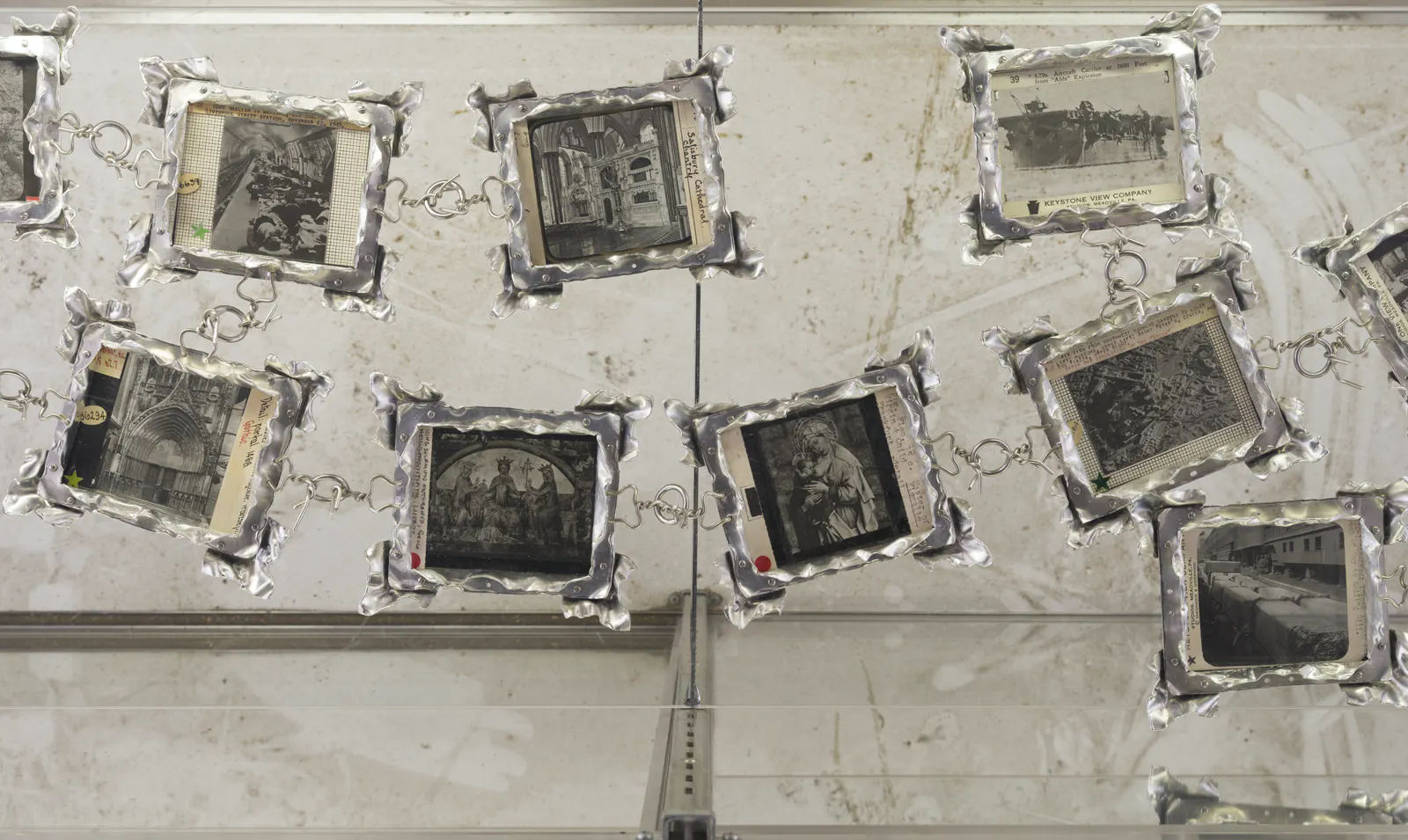

Elaine Cameron-Weir, Florid Piggy Memories brought to you on the wing of the Common Ground Dove/ Dressing for Lectern, 2022. Glass magic lantern slides, pewter, stainless steel, electrical components, display case. 72 x 40 x 20 in. Courtesy of the artist and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff Mclane.

At the head of the gallery, Florid Piggy Memories brought to you on the wing of the Common Ground Dove/ Dressing for Lectern stands like a pulpit. I imagine an invisible preacher orating from the jewelry display case that holds magic lantern projector slides depicting European cathedrals, stained glass windows of Mary, blast walls, warships, and people sleeping in World War II-era bomb shelters.

Elaine Cameron-Weir, Florid Piggy Memories brought to you on the wing of the Common Ground Dove/ Dressing for Lectern, 2022. Detail. Glass magic lantern slides, pewter, stainless steel, electrical components, display case. 72 x 40 x 20 in. Courtesy of the artist and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff Mclane.

Lectern presides in front of this “machine” comprising a military flight jacket hanging from meat hooks, human bones cast in metal, components of airplane fuel tanks painted as black sharks, and bronze reliefs of the thirteenth station of the cross: Jesus’s body taken down from the crucifix. This exploded view is similar to the way an industrial designer envisions their machines. Each element on this implied conveyor belt is suspended by pulleys, with different heavy objects as counterweights: speaker sirens, metal drums filled with aggregate concrete rocks, a bronze statue of the Virgin Mary kneeling in prayer, a fighter jet seat, chunks of alabaster, and a pair of industrial steel fire doors. All together, the work titles read obliquely, like a poem: They Say it Skips a Generation; Joy in Repetition; World Stage Town Crier; Florid Piggy Memories brought to you on the wing of the Common Ground Dove / Dressing for Lectern; Dressing for Windows / Dressing for Altitude / Dressing for Pleasure; Exploded View / Dressing for Windows.

Amid my languishing in the gallery, I want these static things to come alive, to hear the speakers roar and watch the conveyor belts grumble forward. There’s a slippery, teasing quality to the show, an elusive suggestion of movement weighed down by the physical heaviness of the materials. Cameron-Weir cites specific wars and religious iconography, but only as if to say “It’s not religious war history, it’s the heaviness of these objects, but they are also the same.”

George Herms, Clock Tower Monument to Unknown, 1987. MacArthur Park, Los Angeles. Photo: Ezequiel Olvera.

Cameron-Weir is a white artist aestheticizing the weight of European war objects and religious sculptures in MacArthur Park, the living legacy of this country’s filthy military occupation of Latin America. It has the highest concentration of migrants from Central America in California and is often the first destination for displaced people—the tarmac. The artist uses a sculpture of the Virgin Mary kneeling for formal and conceptual purposes, as a convenient signifier, but families here worship Our Lady of Guadalupe as the protective deity of their treacherous exodus to Los Angeles.

Elaine Cameron-Weir, Dressing for Windows/ Dressing for Altitude/ Dressing for Pleasure, 2022. Detail. Fighter jet seat, bronze statue, stainless steel barrel cart, leather jacket, meat hooks, conveyor belt, pulleys, hardware, 144 x 87 x 150 in. Courtesy of the artist and Hannah Hoffman, Los Angeles. Photo: Jeff Mclane.

Ezequiel Olvera is a curator and the director of Court Space, a project that initiates dialogue between the public and private art establishments. His practice is devoted to piercing institutions through projects utilizing critical discourse, site-specific concepts, and radical aesthetics. He is interested in forging a culture of prestige for black and brown artists through elevating the poetic expression within American survivalism, intellectual hustling, and gambling artistic intuition. His writing has been published by X-TRA, Topical Cream and The Museum of Contemporary Art Los Angeles.