For the re:Research column, we ask artists to take us behind the scenes of their work. Sabrina Tarasoff leads us down the primrose paths of her installation at The Huntington for Made in L.A. 2020: a version (also hosted by the Hammer Museum). The exhibition opening is dependent on the LA County Guidelines for museums.

Model of Sabrina Tarasoff’s Beyond Baroque Haunted House currently installed at the Huntington as part of Made in L.A. 2020. Courtesy of Zion Fenwick/Twisted.

The Beyond Baroque Haunted House at the Huntington was my way of reading the canon. It started as a literary séance staged to revive a certain punk lyricism, sexual anarchism, and post-60s malaise that freaked forth from a group of 1980s Los Angeles poets. Needing to speak to the dead, hoping to blow up a certain fin-de-siècle sensibility that resonates darkly in this century, I hopped aboard poetic figures like the death skiff, the corsair, and the space gun to see what fugitive desires fueled their drift. Then everything went to hell. This is not only in reference to the world’s ongoing apocalypse. My past months could be likened to the 1991 film Hearts of Darkness: A Filmmaker’s Apocalypse, which documented the soul-crushing effects of making Apocalypse Now on its director, Francis Ford Coppola. The Made in L.A. biennial unfolded, for me, as a version of Coppola’s grandiose hell: a high stakes production riddled not only with construction issues, financial pressures, and persistent delays due to disease, but more significantly the constant presence of conservative museum bureaucrats basking in the nostalgia of their Vietnam, seemingly reliving the American culture wars of the 1980s, while clutching their pearls and voicing increasingly surreal concerns on everything from my work “promoting illicit drug use” to flagging, misguidedly, the fraught intimacies of Bob Flanagan’s performance poems as sexually deviant content that risks upsetting “the audience,” or what I can only assume to be their Republican donor base. With Disneyland’s doors closed and my head haunted by other ailments, deaths, and disasters, the biennial slowed to near zero: a looping hell-coaster of daily platitudes shelled out by the petite-bourgeoisie of San Marino. Paraphrasing Coppola, “Little by little, I slowly lost my mind.” The ride never ends, and the exhibition’s opening keeps being moved ahead.

The author’s research images. Photo: Sabrina Tarasoff.

Perhaps all that needs to be said is that I was haunted by how the poets in the Beyond Baroque gang fashioned their voices out of material fantasies fitted with all kinds of wild feelings. What stood out initially was a mutual interest in ideas of influence: literary influences, spatial ones, celebrities and the sphere of pop culture, but clearly also the intoxicating atmosphere of drugs, drunken boats, and poetic drift. In the works of the so-called “poet gang,” known alternately as the “young punks,” the “punk poets,” “transgressive writers,” or, to quote Dennis Cooper, “this kind of young gang: Bob Flanagan, Amy Gerstler, David Trinidad, and Jack Skelly [sic]—all those guys,” I poured over pages and pages of quasi-mystical experiences with point source referents. Whatever forces were at work could be dialed down to “little bottles of Inglenook” (Smith), “spilt spiritual milk” (Gerstler), “my throbbing cock, that’s what” (Flanagan), or, as the title of one Steve Abbott poem had it: “grandiose delusions as a form of escape from reality resulting from a feeling of…” My question became: a feeling of what? Motion blur? And what does that mean when put to verse? These poems were anxiety dreams fueled by love and limerence, homages to dead French poets and frail haiku, haunted hayrides and POV ride-throughs of theme park attractions; they tracked hell as a place where the heart is, ideas of home, lyric harbors, slowly revolving ideas, animatronics, and cartoon characters, all animated in the fast pace of Los Angeles in the ’80s. “The ride is sim-death, the ultimate industrial form of three acts in a few seconds,” writes Norman Klein. “To achieve the ride is the ultimate compliment.” I wanted to achieve the ride.

Ed Smith, who committed suicide in 2005, achieves the ride. His vision for poetry was like being blasted into space on a Verne gun. The catalyst in fantasy: sim-death. In a poem titled “three suicidal fantasies,” Smith’s “I” imagines being on an airplane and swallowing a large number of “bogus ’ludes without regurgitating from going too fast or gagging on powder from the pills.” His voice is undue yet assured. The writing follows a manic rhythm of thought as though the momentum alone could fulfill his wish. Despite his “chemically induced dizziness,” he finds his seat without incident and “pretends to sleep.” The reader is dizzied and disoriented by the run-on sentence’s warp speed. If Smith’s “flight” departs from a space of personal darkness, its final destination is darkness’s impact on verse. The second fantasy is fitted into a small room with shut windows and a Sylvia Plath-esque plan, which even the poet seems unsure about. Smith writes, “Not yet… almost, but not yet. I don’t know if this is going to work.” His hesitation sets the reader up for what follows, which is nothing; no resolve. There is also no third fantasy, despite the title’s promise—just a ledge at the end of the poem and the thrill of a sudden drop.

Left: Devil magistrate from Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride, Disneyland Park and Resort, Anaheim, CA. Photographer unknown. Right: Poster for a reading at Beyond Baroque, January 6, 1985. Photo: Sabrina Tarasoff.

Achieving the ride in writing is about the limitless motion of anxious day-dreaming, language’s special FX thrilling the mind into suspending disbelief for the duration of a poem’s run. Motion blur is crucial, like how Disneyland’s Jungle Cruise blurs in my head with the Proustian roman-fleuve: a narrative of drift and spectacle. Jungle Cruise, really, should be re-themed as an acid-laced Apocalypse Now slow-show river ride replete with hallucinogenic pangs of color and light, paranoia, delirium, and irrationally cold beer. Splash Mountain should be turned into a Paradise Lost-themed ride where passengers are chased by Satan from Pandemonium into Paradise, where they’d be tempted with knowledge, sex, and death in verdant fields, and then be dropped 90 feet back to society to think it over. Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride should stay exactly as it is: a drunken dérive through the Thames Valley that winds you to hell. I thought often about this exodus into the English countryside in the center of Anaheim’s Fantasyland: barrels swinging in forced perspective, cops chasing you, sleepy railroad operators missing sight of your motorcar as you enter a dark tunnel and… die? There is a trap door in hell that returns you to Disneyland. You could ride this loop forever: to hell and back again and round and round. Klein’s idea is that rides were developed to reenact the anxieties and thrills of urban life at the moment of its industrialization. Like the mind in its more manic moments, rides swerve awfully close to uncomfortable truths, occasionally crashing into—through—walls, secret passages, trains (of thought) that lead straight to various damnations.

Mr. Toad as Thomas Gainsborough’s Blue Boy (1770) from Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride, Disneyland Park and Resort, Anaheim, CA. Creative Commons license BY-ND 2.0. Photo: Loren Javier.

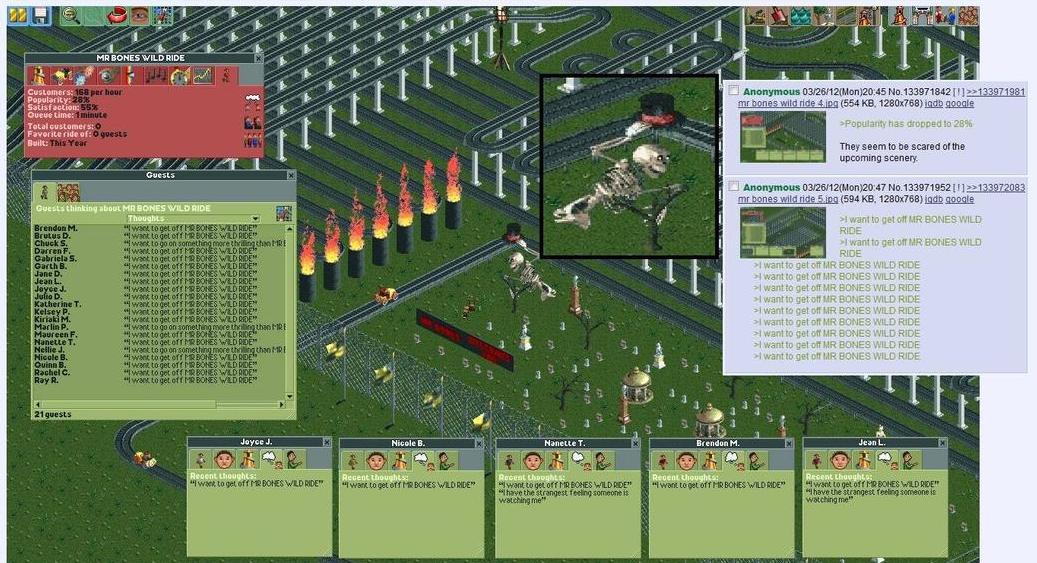

It is notable that Mr. Toad’s Wild Ride starts off in Toad Hall, where hangs a remake of Mr. Toad as Gainsborough’s Blue Boy (1770). The original hangs at the Huntington. This is a coincidence to the biennial project, but not insignificant. L’enfer. The Mr. Bones’ Wild Ride meme flashes in my head on a daily basis. It would be remiss not to hone in here, so I digress: Mr. Bones’ Wild Ride was a custom-designed “hell-coaster” made on the computer simulation game Roller Coaster Tycoon 2. In 2012, an anonymous user posted a description of the ride on 4chan, explaining that the 30,969-foot coaster took four years of game time to ride from beginning to end, with additional screenshots of the mechanical screams of the thirty-eight virtual passengers on board: “I want to get off MR BONES WILD RIDE!” “I want to get off MR BONES WILD RIDE!” “I want to get off MR BONES WILD RIDE!” At the end of the roller coaster’s loop, passengers exited to a long pathway leading to nothing but another entrance to the ride, passing, as they re-embarked, an animatronic skeleton tipping his top hat towards a sign that read: “The ride never ends.” In the years following, numerous other hell-coasters have emerged on various theme park simulation games, with the creative fanbase of roller-coaster sadists generating evermore precise ideas, like the Kairos—“an unrelenting doom coil of a ride that takes over 3,000 in-game years for unsuspecting guests to complete” due to a quirk in the game’s mechanics: “When a roller coaster travels along a track of constant height its speed exponentially decays toward zero but never stops.” As one YouTube commentator noted, “Children are born on this roller coaster, and die on it. A civilization rises on it.”

Mr. Bones’ Wild Ride meme, 2012. Anonymous author.

I wonder if this was the same civilization that Ed Smith called out to in his unpublished epic, “Return to Lesbos.” “Does it mean civilization,” as he wrote, “is / threatened?” No doubt the roller coaster, like the dark ride, or arguably the haunted house, is an existential artifact created to fulfill our need for intensity within an increasingly meaningless world, even—especially—when enclosed, and so edging closure, finitude, failure: the end. Within the enclosed loops of (poetic) propositions like Mr. Bones’ Wild Ride or the Kairos, there is a desire to see what happens when the rules of the game, or some psychosocial carrying capacities, or language, are stretched out to fantastical limits, “whence the relation,” as Blanchot would have it, “between the work of art and the encounter with death: in both cases, we approach a perilous threshold, a crucial point where we are abruptly turned back.” Back on the ride? The momentum gained by these poets was an effort to match, on a page, the very violence felt in the act of writing as a signification of existence. It is the zero approached, yet never reached, when attempting to inscribe ourselves into history. In a poem titled “Denial,” Smith writes: “I would never do this. / This isn’t me. / You’d never catch me being words on paper, / Being written down, / Being in a position where / I could always be come back to and read.”

Fait accompli.

Portrait of the author. Courtesy of Katy Shane. Photo: Katy Shane.

I keep asking myself what is at the heart of hearts of my obsession with rides and riverlike writing. I have dreams of crashing into hell. At some point, I fall in love: it’s pointless. The haunted house came to stand in for the missing shocks and sense of self that slowly dissipated during the spring. Summertime should have been spent on secret assignations, writing, woozy decadence, and forest walks. (Or, their literary equivalents, given “le situation un peu particulier,” as the wine bar beneath my apartment calls it.) Instead it was all bureaucrats and facilities staff serving me violent indifference that I substituted for food, becoming thinner every day. “The discourse of reason is the true violence,” or so says Guattari, and so much seems true. I could no longer support courting my own nothingness, for no return, with the increasingly nauseating sense that I was validating the Huntington’s rather transparent desire to reap from contemporary art’s cultural clout, at least insofar as any hints of “subversion” remain strictly within the comfortably canonized and preapproved histories of the intellectual petite bourgeoisie running the show. I am feeling Coppola-esque (minus the megalomania), slowly going crazy in my own drift. “To not answer,” Coppola says in Hearts of Darkness, addressing his own rhetorical question on how to end his “psychedelic war,” “would be to fail.” An impasse. Ride achieved. There is a destination—I know it—but the big blasts around me make it hard to keep sight. x

Sabrina Tarasoff is a writer formerly based in Los Angeles. She would like to thank Lauren Mackler, Ikechukwu Onyewuenyi, Myriam Ben Salah, the poets, Zion Fenwick, Rose Truhlar, Kyle Warner, and Aurora Persichetti for keeping her sane.