Meriem Bennani’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles, Guided Tour of a Spill at François Ghebaly, is a roaring, thumping, fortissimo phantasmagoria of music and video, montaged across screens and furnished with whimsical sculptures and seating. Building upon “Life on the CAPS,” her extended project about a fictional island in the middle of the Atlantic that becomes a locus of diasporic culture and resistance, Guided Tour of a Spill gives the viewer pieces of a world born entirely from Bennani’s mind. Of course, no artist is an atoll, and Bennani’s works channel a range of undiluted influences, from Moroccan YouTube stars to bus stop advertisements to friends’ techno tracks. Juliana Halpert FaceTimed Bennani in New York from the gallery, while letting the saturated sights and sounds of the show seep in.

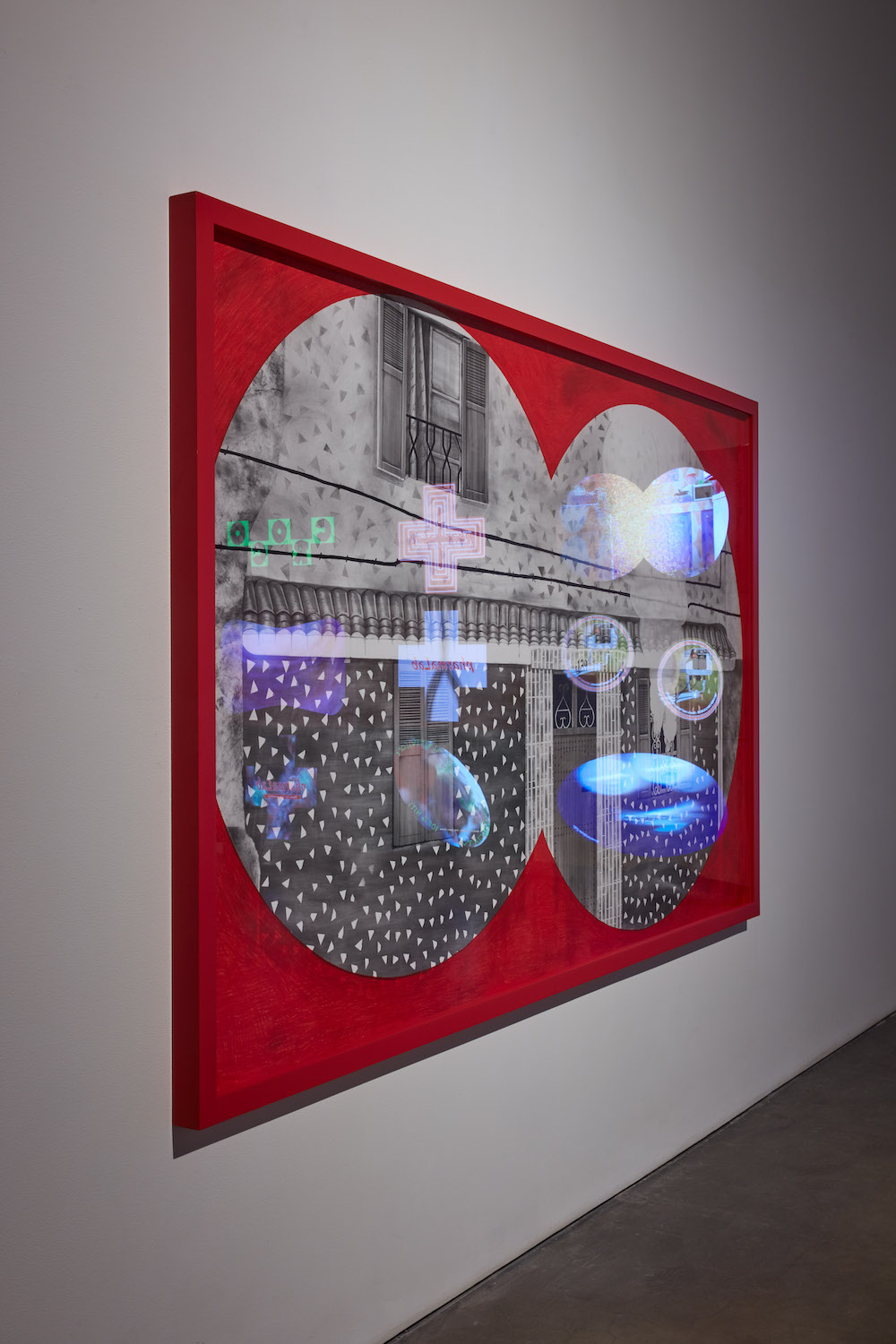

Meriem Bennani, Routini Zip (detail), 2021. Charcoal powder, crushed pastel, and pencil on paper in artist’s frame, 52 1/2 x 93 1/2 in. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

Juliana Halpert: First things first—what is the CAPS, and where did this idea come from?

Meriem Bennani: My idea for the CAPS was first born in 2016. I had been aimlessly doing some research on quantum physics—simply because it’s always portrayed as this incredibly complex, incomprehensible thing—and I realized how related it was to the concept of teleportation, which I had also been thinking about a lot. In quantum physics, teleportation isn’t actually so surreal. It’s theoretically possible, at least with light particles.

I began to imagine a future in which humans can teleport. Keep in mind that Trump had just been elected, and the first thing he did was sign the Muslim ban. And although I’ve had it easy compared to so many migrants, I’ve had to deal with visas and seemingly bottomless bureaucracy for around fifteen years. I was thinking about how countries would start to freak out about their borders and illegal teleportation. Governments would quickly try to regulate it. What would happen if someone was intercepted by the state in the middle of a teleportation? How would that interference affect your body? It felt like a useful analogy for the trauma of crossing borders, and for migration in general.

Meriem Bennani, Quartier Cuba (detail), 2021. Charcoal powder, crushed pastel, and pencil on paper in artist’s frame, 52 1/2 x 85 1/2 in. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

In this world, I figured that governments would have temporary holding areas for migrants who had been intercepted during teleportation. I had been looking at photos of huge military bases in the middle of the ocean—they’re basically cities on boats, with Starbucks and things like that. So I started to imagine an island somewhere in the Atlantic where these migrants would be held, presumably for a long time. Countries wouldn’t know what to do with them; they’d be stateless. Maybe they’d stay on this island for generations, a city would slowly develop, and new diasporic cultures would take shape.

Now that I had this world, I wanted to start making documentaries about it, inside of it—to build a larger saga about this place across a trilogy of films and several exhibitions.

JH: Why is it called “the CAPS”? Does that stand for something?

MB: I was thinking it’s like a “halfway capsule.” I liked that “CAPS” is also like “capital,” as in the centers of the world, and that a small island of migrants would not be considered a capital. Also, that it could be an abbreviation of “capitalism.” It’s mysterious and flexible.

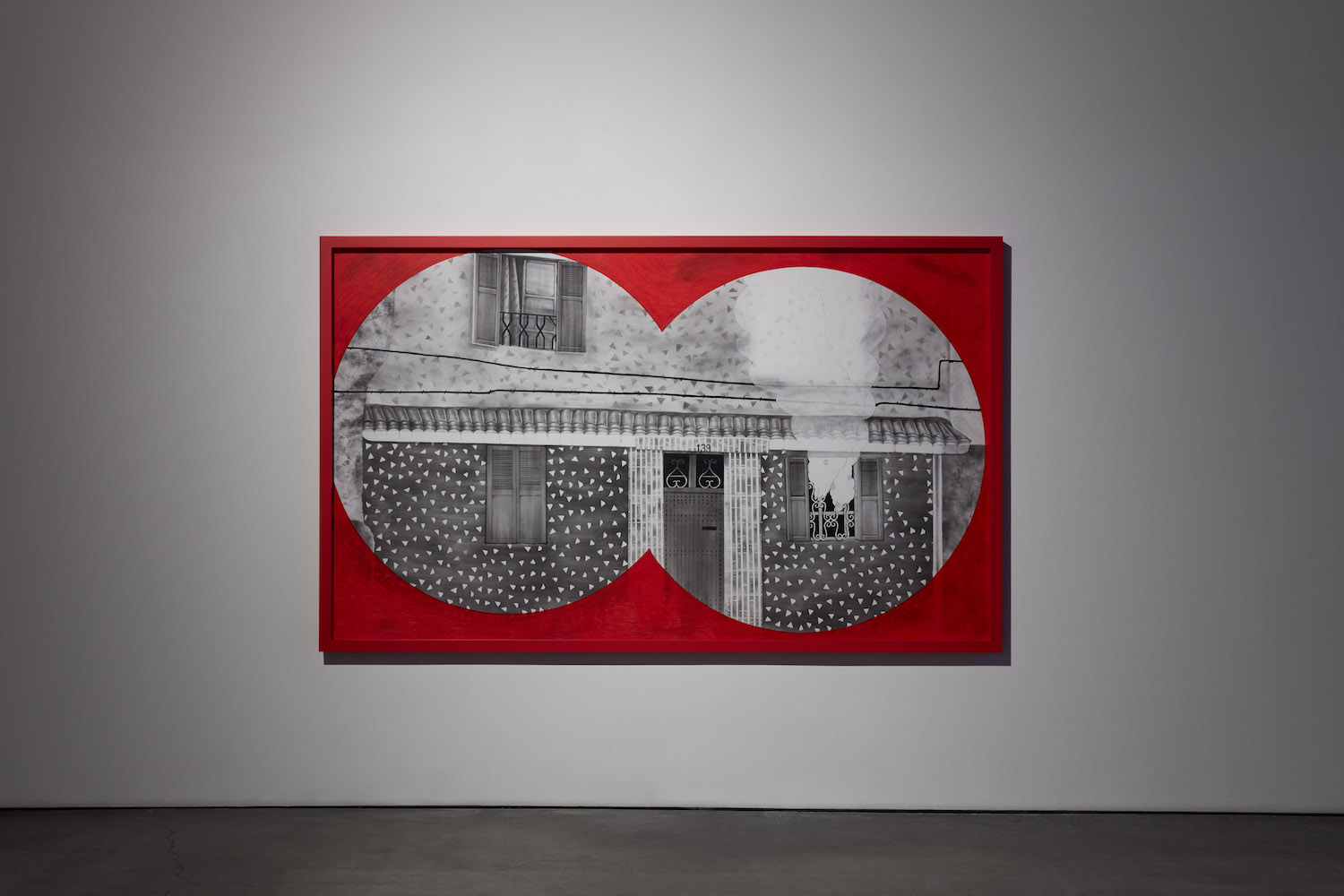

Meriem Bennani, Quartier Cuba, 2021. Charcoal powder, crushed pastel, and pencil on paper in artist’s frame, 52 1/2 x 85 1/2 in. Installation view, Guided Tour of a Spill, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, March 6–May 1, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

Meriem Bennani, Quartier Cuba, 2021. Charcoal powder, crushed pastel, and pencil on paper in artist’s frame, 52 1/2 x 85 1/2 in. Installation view, Guided Tour of a Spill, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, March 6–May 1, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

JH: How and where does this show, Guided Tour of a Spill, fit into the larger arc of the CAPS universe and project?

MB: As I see it, Guided Tour of a Spill is an early staging of the larger story about the island. It’s like an establishing shot. All the elements of this show exist within that world. I definitely wanted these works and their installation to be a playful, explorative, and freeform take on the larger project. So many of my installations and shows in the past six years have comprised one main video piece that’s between twenty and forty minutes. I needed to try some new things this year and see what happened.

JH: I will admit, I was surprised to be greeted by two large drawings when I walked into the gallery. I’d always thought of your practice as very dialed in to digital media and the internet, digesting and spitting them out in these wild, highly fabricated, futuristic installations. But here, charcoal and pastel on paper! Can you tell me more about these two works—Quartier Cuba and Routini Zip (all works 2021)—and what made you decide to draw?

MB: Before I ever made a video, I always drew. That was my primary medium. But now I never have the time or space to draw. I’ve missed it, it’s as simple as that. And knowing that I was going to be in Los Angeles for four months to prepare this show, I really wanted to make pieces from scratch, with fresh energy. LA is good for that, and for drawing; there’s so much space, and good light. It felt wrong to just be in the dark on the computer.

These drawings very much belong in the world of the CAPS. Quartier Cuba comes from a shot in Party on the CAPS where I’m in the back of a cab driving through a part of Casablanca by the ocean. I’m filming the view outside, and you can hear the cab driver telling me, out of frame, “We call this neighborhood Quartier Cuba!” I asked why, and he says, “Because you can find anything you want. If you want to sniff or snort anything you’ll find it there. You want snakeskin? You’ll find it.” I think of this as such an old, Cold War-era idea of Cuba, from before the revolution.

Guided Tour of a Spill, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, March 6–May 1, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

Meriem Bennani, Routini Zip, 2021. Charcoal powder, crushed pastel, and pencil on paper in artist’s frame, 52 1/2 x 93 1/2 in. Installation view, Guided Tour of a Spill, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, March 6–May 1, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

The other work, Routini Zip, is somewhat of a digression. There’s this hashtag, #routini, which has generated a new subculture among Moroccan YouTubers over the past year or so. Women film themselves doing their domestic routines, like cleaning their house, cooking, doing any kind of housework, really, under the guise of instructional videos. The videos are actually completely erotic. The camera is usually focused on their ass. The women will be wearing very tight clothes and be like, “Oops! Sorry, I dropped something,” and bend over. It’s so sexual. I watched so many of these videos. Some have millions of views, whole stories develop about each woman, and sometimes there’s drama between them. I love that it’s a thinly-veiled erotic form, but one that is made totally outside of the globalized aesthetics of what we consider pornography. Instead, so much of their eroticism comes from how the women’s sexuality is intertwined with aspects of everyday Moroccan life. It’s cool to see a form of erotic videos that is aesthetically Moroccan, emerging from within the culture.

Routini Zip was drawn from a screenshot of one of those videos. I thought the kitchen and its colors were really beautiful. Instead of drawing the woman, I added in this explosion, as if she had just teleported somewhere.

JH: What is the “CAPS ZIPS” graphic on the bottom-right corner?

MB: It’s like the channel logo—CAPS TV!

JH: I’m also curious about the drawings’ scale. They’re quite large!

MB: I’ve always drawn at this scale. It just makes sense with my body. I’m not really good at small things. I just have a lot of energy.

Meriem Bennani, Sidewalk Stream, 2021. Installation view, Guided Tour of a Spill, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, March 6–May 1, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

JH: Next to Quartier Cuba and Routini Zip is Sidewalk Stream, nine channels of video encased in a big grid of coated steel frames. Between their neon colors, glowing logos and leitmotifs, and the shapes of the windows cut into the steel—ovals, circles, the first-aid “plus” symbol, the same binocular shape that frames the view in Quartier Cuba—to me, this work really smacks of signage. Less television and more… LCD monitor at a mini-mart. What are we looking at here? And, what is “PharmaLab”?

MB: The hardest thing about world-building is finding ways to flesh out details without becoming too focused on how things look and feel. Worlds need stories and perspectives, too. I will say that Sidewalk Stream may be the most purely visual and most abstract work in the show. It’s more painterly. I was imagining a sort of ad wall or bus stop ad on the CAPS. PharmaLab is the pharmaceutical brand on the island; the trauma of being intercepted mid-teleportation can have a lot of physical repercussions. And, in Party on the CAPS, there’s a pharmacist character, who is played by my mom.

One of the screens shows YouTube videos—the idea was that it’s an oldies channel playing songs from the CAPS inhabitants’ origin countries. A big theme in North African music is l’ghorba—a specific kind of melancholia about missing home. A lot of songs reminisce about the beautiful days back home, a place that has become so romanticized in one’s mind.

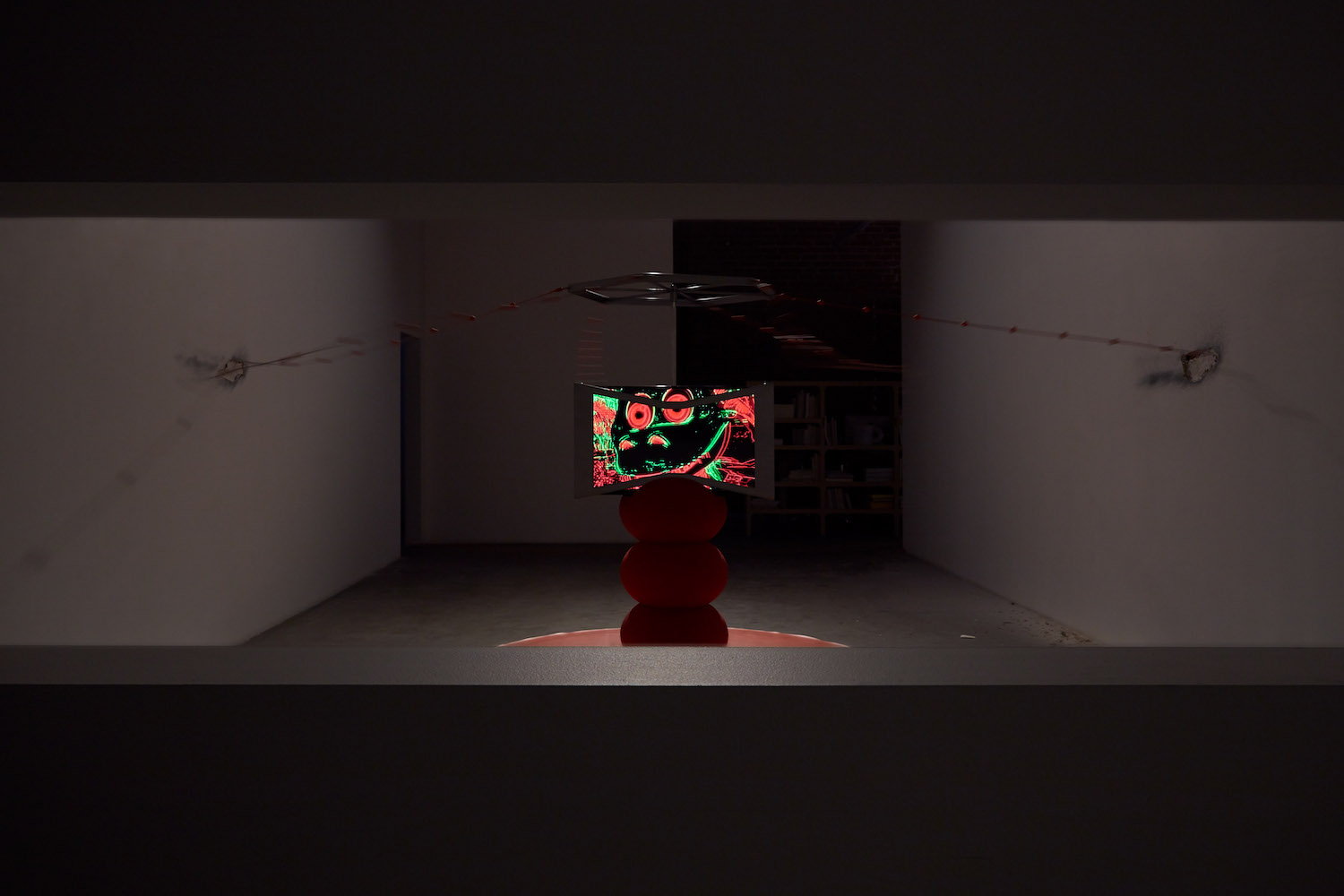

Meriem Bennani, Umbrella Slap, 2021. Steel, flatscreen monitors, media players, motor, epoxy resin coated foam, pleather, plastic coated cord, 4K digital video, 1:21 min., 42 x 42 x 72 in. Installation view, Guided Tour of a Spill, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, March 6–May 1, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

Guided Tour of a Spill, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, March 6–May 1, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

JH: Moving into the largest room, I’d love to hear you talk about this installation: this big screen, all these red, glowing, square stools. How do all of these sculptural accoutrements contribute to a viewer’s experience of Guided Tour of a Spill (CAPS Interlude), the video playing in this room? What kind of physical environments are you referencing or hoping to conjure?

MB: In the installation for Party on the CAPS last year, I made similar stools, but they were cylindrical—I want each install to stay in the same kind of aesthetic family, but remain unique, too. I like that when someone sits on the stool, their butt eclipses the light. I really enjoy involving people’s bodies as much as possible in an installation. I want to create an active viewing experience, to keep people alert, and avoid a sort of sleepiness that art viewing often has. But I also want the stools to be comfortable enough to make people watch the entire video.

This is the first time I’ve done a video installation that is single channel, with only one projector. It’s more straightforward, but this screen still needed to be very specific. I always want my videos to look like they’re coming from a place that isn’t rooted in the art world and the gallery. I’m not referencing these worlds. I’m referencing others—drive-ins, homemade projection screens, sound walls behind DJ booths. I want the viewer to understand that the screen is integral to the work, not just a generic device to be ignored.

Meriem Bennani, Guided Tour of a Spill (CAPS Interlude), 2021. Wood projection screen, LED lights, steel, epoxy resin coated foam, pleather-upholstered stools, 4K digital video, 15:49 min., 141 x 250 x 25 in. Installation view, Guided Tour of a Spill, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, March 6–May 1, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

Meriem Bennani, Guided Tour of a Spill (CAPS Interlude), 2021. Wood projection screen, LED lights, steel, epoxy resin coated foam, pleather-upholstered stools, 4K digital video, 15:49 min., 141 x 250 x 25 in. Installation view, Guided Tour of a Spill, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, March 6–May 1, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

JH: Speaking of DJs—at moments it feels pretty clubby in here. The bass really booms, and the thundering soundtrack to CAPS Interlude seems so integral to the work, the pace, the feel of the whole thing.

MB: Yeah, for this show I was determined to be a bit more unapologetic, which is really hard for me to do. And, I wanted to have fun. The music is so central to generating that. It’s mostly my friends’ tracks. Someone would send me their new album and if I liked a song I would try it with the footage, often editing the film to match it more.

I definitely meant for it to be so loud that it’s difficult to talk over. I miss being in spaces with other bodies without having to talk—the kind of communal experiences you get at clubs, weddings, dance parties, any of the stuff we haven’t been doing. I need people to feel it. The music vibrates in your chest. I wanted this show to slap you, where you feel rage and joy and all these visceral feelings, stripped down from this need to be articulate all the time.

JH: That’s a great transition to the work around the corner, Umbrella Slap. I’ve truly never seen anything like this. How did you come up with the idea for this contraption, and what is its role in this show?

Meriem Bennani, Umbrella Slap, 2021. Steel, flatscreen monitors, media players, motor, epoxy resin coated foam, pleather, plastic coated cord, 4K digital video, 1:21 min., 42 x 42 x 72 in. Installation view, Guided Tour of a Spill, François Ghebaly, Los Angeles, March 6–May 1, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and François Ghebaly, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

MB: It’s another work with which I was trying to be a little more angry. I have anger, like everyone else, but I am always pretty polite, on the sweeter side, maybe. I didn’t want to conceal my anger. This piece is pretty literal—it’s just slapping! It was born from a desire to want to slap something. On the opening day, we put these metal pieces on the ends of the cords so they would make sound. By the end of the day, it had completely destroyed the walls. There was plaster everywhere. We had to slow the motor down. I tried to be less polite for one second, but after only one day, I had to dial it back!

JH: Oh, I hadn’t realized—you’ve been censored! I want it to go full slap all the time.

MB: We didn’t really care about the walls, the gallery was fine with destroying them, but the motor is a pretty complex system, so when the cords bounce back from the impact with the wall, it can fuck up the machine and the whole piece might break. Now it looks more like a carousel or a ride, which is kind of cute. But you can still see the damage on the walls, which I think produces a nice tension. The work is placed at the center of the show—I see it as a heartbeat, or a metronome. When it was hitting the walls, it had this incredible rhythm, which worked nicely with the music, but now it’s a bit more ominous and threatening. You can totally still see what it’s capable of. x

Meriem Bennani is an artist based in New York. She has mounted solo exhibitions at Foundation Louis Vuitton, Paris; CLEARING, The Kitchen, and MoMA PS1, New York; and Art Dubai. Her work was included in the 2019 Whitney Biennial and group exhibitions at the Jewish Museum, the Shanghai Biennale, and the Public Art Fund, among others. In collaboration with Orian Barki, Bennani created the viral, early-pandemic video series Two Lizards, now in the collection of the Museum of Modern Art, New York.

Juliana Halpert is an artist and writer from Vermont living in Los Angeles. Her writing has appeared in Artforum, Bookforum, Art in America, and Frieze.