The Dispatches column delivers reports and diatribes from the front lines of contemporary art. Here, Travis Diehl searches for home among the homesteads of the Mojave Desert during a visit to the thirteenth and final High Desert Test Sites biennial in April 2022.

Windmills between Joshua Tree and Palm Springs. Photo by the author.

To be site specific in the twenty-first century is to find a home. Andrea Zittel once told me that the trick to building your own house in the High Desert of California is to do it in phases. As long as each addition stays small, under the 120 square feet requiring a permit, the San Bernadino County folks won’t look too hard. The tactic is an inversion of the 1938 Small Tract Act, wherein, if you built a permanent structure of habitable size (at least 120 square feet), the government would sell you the five surrounding acres at cost (as if it was theirs to begin with). In the 1950s, so-called jackrabbit homesteaders flooded Yucca Valley along the freshly paved Highway 62, many of them veterans of the World Wars looking for peace and quiet and the salubrious dry air of the Mojave. Whether talking to tourists, artists, townies, goat herders, knitters, car collectors, or speculators, real estate is the currency of conversation.

In Pipes Canyon, east of Pioneertown, Rachel Whiteread’s Shack I and Shack II calcify this frontierist ideal. To make the sculptures, Whiteread applied her signature full-scale method of casting negative space to a pair of quintessential homesteader cabins. The results bear the slots and depressions of beams and lintels and shallow roofs, the odd negative reliefs of wall sockets and light switches. In the scrub nearby, incongruous with the sculptures’ fresh, barely weathered concrete, lie rusted bedframes and middens of corroded canned food. Whoever built these cabins didn’t stick it out, taking their reasons with them.

Rachel Whiteread, Shack I, 2014. Permanent installation. © Rachel Whiteread. Photo by the author.

Photo by the author.

The Whiteread shacks are on the map as part of the thirteenth High Desert Test Sites (HDTS) biennial. The series was started twenty years ago by a group of Los Angeles artists (and New York artists new to the Southwest), including Zittel, who has shepherded it ever since. The event has remained an aesthetic foothold for this cohort, maintained especially by Zittel’s famous art/life work, A-Z West, a compound just a few hundred yards south of Highway 62. More than the uninhabitable Whiteread cabins, A-Z confounds any distinction between art and architecture. Zittel lived in a house she furnished and expanded piecemeal, built a studio, wove her own clothes, and hosted guests and patrons in a suite of clamshell camping pods of her design, folded into the rocks above a wash. Between the highway and the main house, untucked from the hill’s rise, Zittel built a series of abstract sculptures from cinderblocks that, except for their black paint jobs and evident formalism, could be mistaken for any number of desert ruins.

Rachel Whiteread, Shack II, 2016. Permanent installation. © Rachel Whiteread. Photo by the author.

I’d assumed the Whiteread casts were recent, since they represent such an appropriate culmination of HDTS. I learned during the biennial’s opening weekend that these negative shacks were commissioned by a private collector on what is now his property, in 2014 and 2016. The biennial started out completely ad hoc but has gradually professionalized. This edition is the last. The Wonder Valley homesteader cabins Zittel outfitted as minimalist rentals have been sold. Zittel has also wound down her A-Z project, moved to a new house further down the highway, and handed off her longtime property to HDTS. The biennial will no longer operate as such; instead, HDTS will use the A-Z campus to stage artworks and experiences on a different timescale.

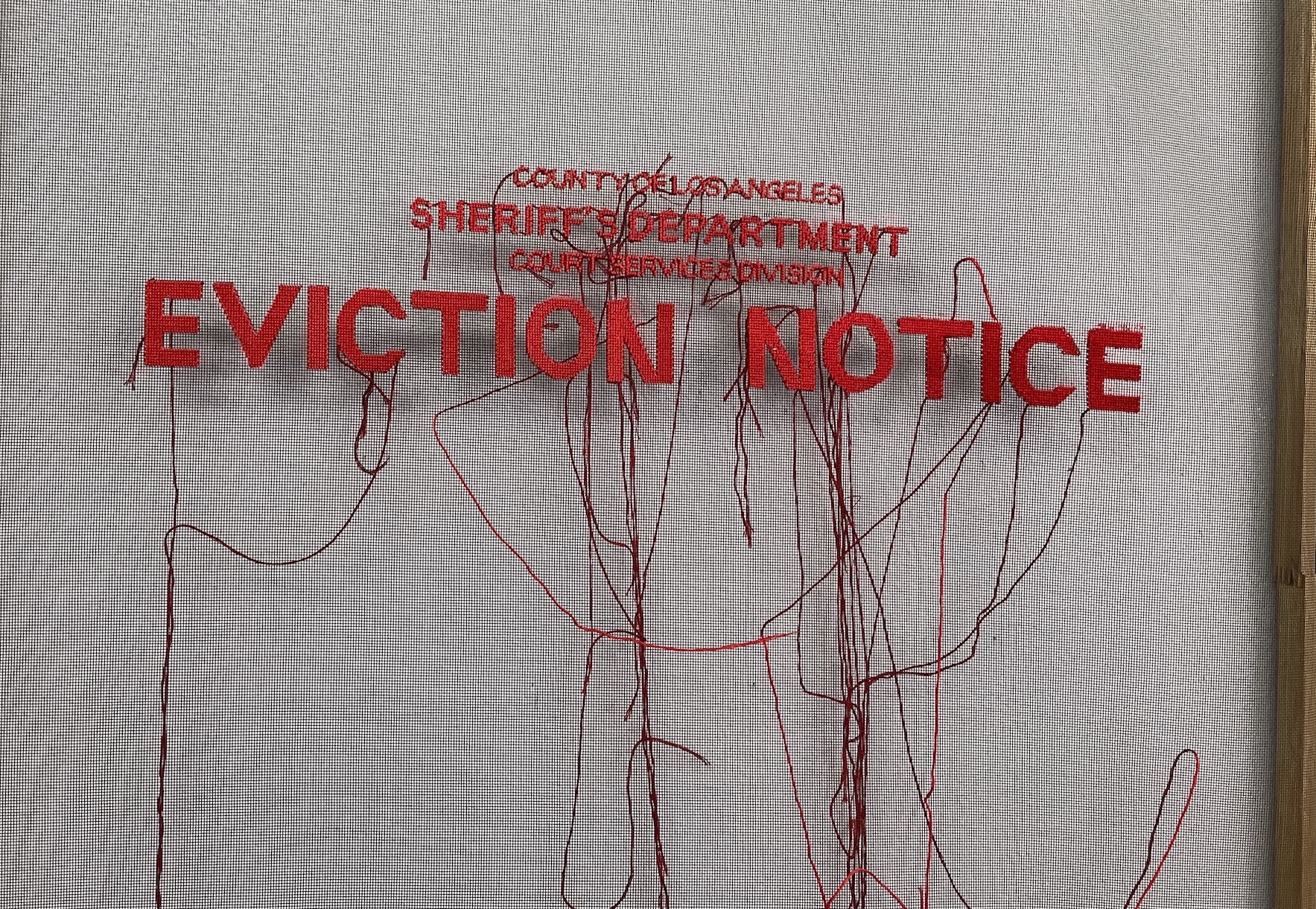

Syd Abady, In the Dream House, 2022. Detail. Cotton thread on window screen, 36 x 80 in. Photo by the author.

Elsewhere in Yucca Valley, Joshua Tree, 29 Palms, Wonder Valley, and Flamingo Heights—cannily named neighborhoods carved up by real-estate brokers like a desiccated Brooklyn—homesteader cabins have lent their bones to hundreds of renovations. Thousands of Airbnbs clot the landscape, and their tenants overwhelm the local restaurants and shops. Joshua Tree used to be a place where a veritable foreign legion of misfits could find a sort of sunblasted peace—community if they wanted it or solitude if they didn’t. Artists, too, have been buying property out there for decades, at least since the 1970s—Ed Ruscha before Noah Purifoy, Purifoy before Zittel—and seemingly an entire generation of Los Angeles art school professors have a foot on the ground in these parts. This is still possible, I guess—several of my peers from the MFA program at CalArts own property in the Mojave—but these are often their primary residences, not winter nests. The poet Anthony McCann, who teaches at CalArts, writes in his book about the Oregon standoff at Malheur that, priced out of Los Angeles County, he commutes to class from Mojave. Stephanie Smith, a Harvard-trained architect, has had a clutch of Instagrammable rentals since 2010. Ry Rocklen, an LA artist who lives in Yucca Valley full time with his family, has started a gallery called Quality Coins in a shopping mall. During HDTS, the group show there included two pieces by Syd Abady, one of my guides to the local biennial—a for sale sign and an LA County Sheriff’s eviction notice cross-stitched into a window screen and a screen door, respectively.

Joshua Tree’s gathering saturation shadows the feeling in Los Angeles that artists and dealers can’t afford to take too many risks. This is the culmination of the process of LA becoming a place where artists choose to live, where MFAs stay on after graduation, where folks from New York and Europe can find their piece of light and space. The cliches of the frontier remain, but the arrow of progress has ricocheted off the Pacific, and the flow of the country has turned against itself. Joshua Tree is over, but LA is over more.

Rachel Whiteread, Shack I, 2014. Permanent installation. © Rachel Whiteread. Photo by the author.

When I moved to LA from North Carolina, the Mojave was the most exotic, exciting part of California. There’s simply nothing else like it in the United States—remote, alien, but also banal, impoverished, a mix of prefab homes and greasy spoons. The Marlboro Man at Del Taco. The fulfillment of a national prophecy. Now, as rents climb in the big city and natural wine shops open on Highway 62, parts of Yucca Valley rival much of Los Angeles for budget hipsterdom. The 2022 High Desert Test Sites is titled The Searchers, just like the John Ford Western starring John Wayne. Its famous final shot, inside a cabin looking out, frames the brutal hero in the doorway of the homestead, buffered by the sand and sky, before the black door closes and the country moves on. The desert has become a home. x

Travis Diehl is Online Editor at X-TRA. He lives in Brooklyn.