The Dash column explores art and its social contexts. The dash separates and the dash joins, it pauses and it moves along. Here, Juliana Halpert trails photographer Reynaldo Rivera through a lost Los Angeles by way of his new book, Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City, edited by Hedi El Kholti and Lauren Mackler, and published by Semiotext(e) this November.

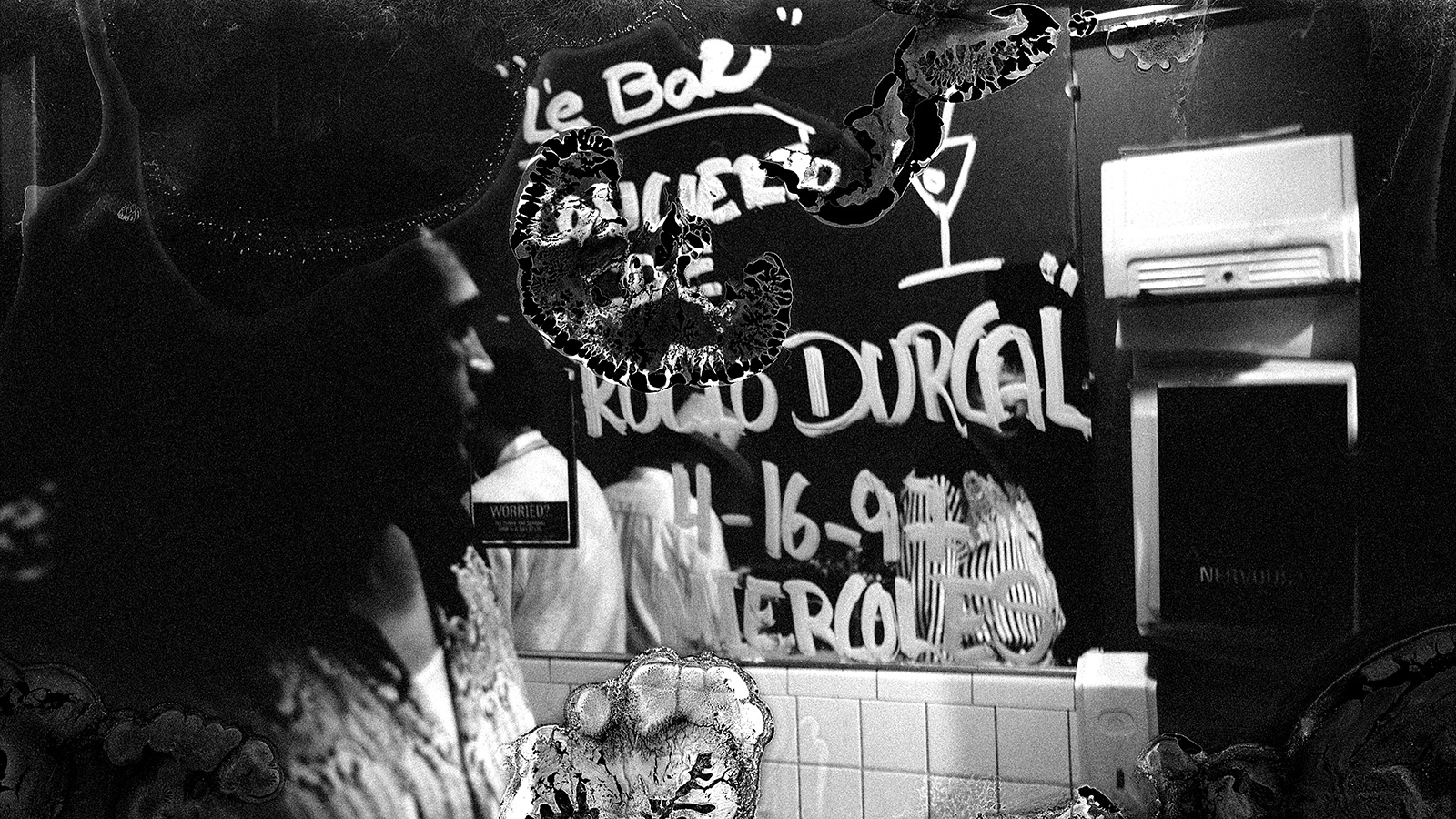

Reynaldo Rivera, Le Bar, 1997. Silver gelatin print from fire-damaged negative, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

Roughly two years ago, Reynaldo Rivera emailed his longtime friend Vaginal Davis from his apartment in Lincoln Heights, Los Angeles. At the time, Rivera was putting together his first book of photographs, and the two artists had decided to strike up a written correspondence to serve as one of the book’s companion texts. Over four paragraphs, Rivera began to rove through his memories of a bygone youth spent in a bygone LA: old apartments on Sunset and Fairfax, his mother’s “lesbian parties,” his family’s migration across the city—“kind of like the Wildebeest”—and his own adolescent drift from “gangs to androgyny.”

One week later, he wrote to Davis again, newly abashed: “Oh lord Miss Vag,” he opened. “I just read what I wrote you and realized it’s unreadable. I got real stream-of-consciousness and it’s all over the place. Plus,” he added, “I went into stuff that I maybe should have just kept it [sic] out.” Davis replied the next morning. “Darling Rey,” she wrote, “Please don’t second-guess yourself. What you have written is visceral and immediate. Don’t overthink it. It’s delicious and raw. They can clean it up later.”

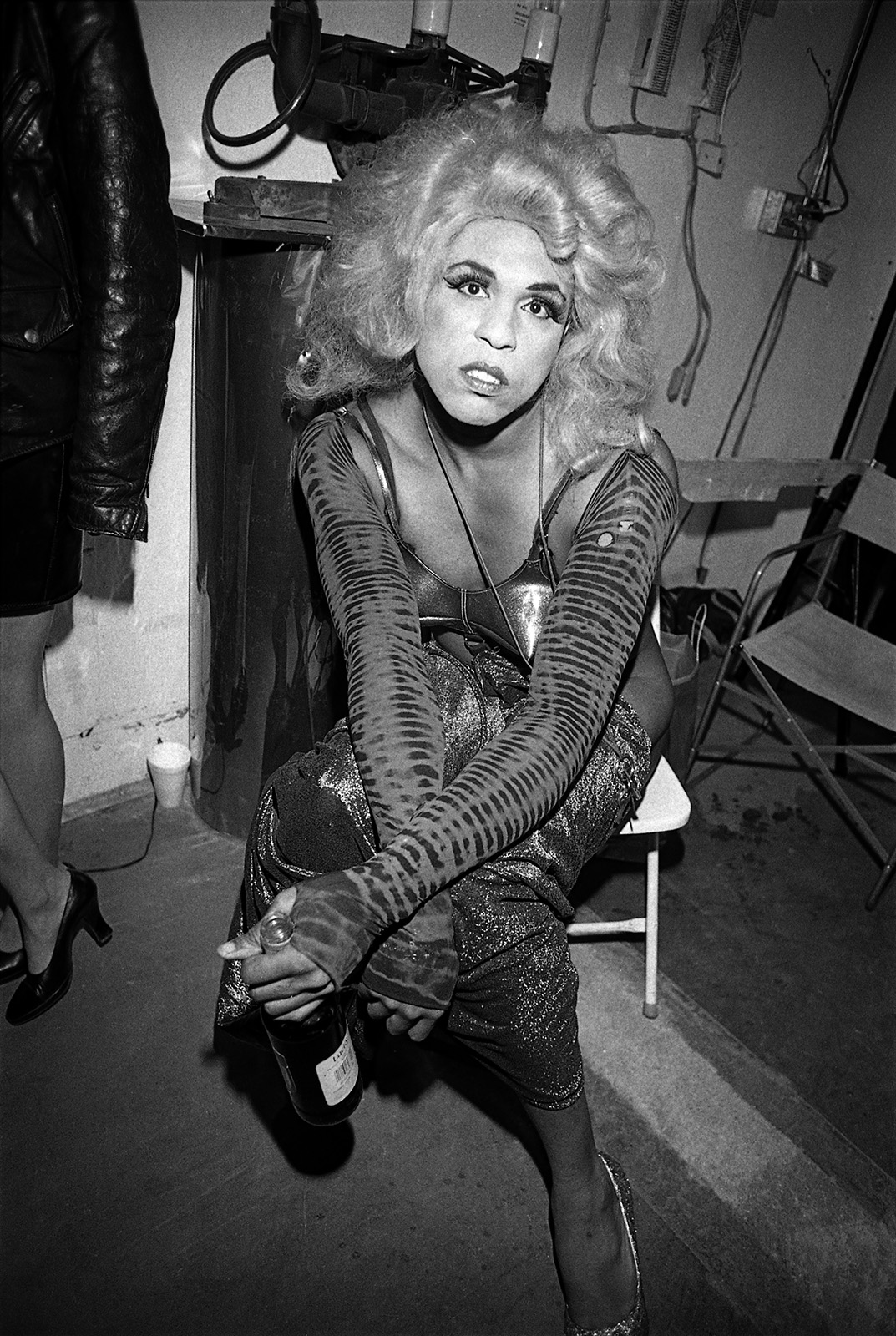

Reynaldo Rivera, Vaginal Davis, Downtown LA, 1993. Silver gelatin print, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

At last, Semiotext(e) has published Reynaldo Rivera: Provisional Notes for a Disappeared City. Thankfully, it does not feel cleaned up—not in the way that Rivera’s old LA haunts now do. To write about what happens inside its pages in any way that is not visceral, immediate, delicious, and raw would amount to nothing short of gentrification. The book must be spared the sanitizing treatment of too-taut, overly decorous art-speak. Its own tone is equal parts gritty and glamorous, somehow both tender and toughened, a pair of shiny high heels atop a dirty carpeted floor. Nearly 200 black-and-white photographs by Rivera, an essay by Chris Kraus, a story by Luis Bauz, and that email correspondence between Rivera and Davis, which clocks in at twenty pages, give us all they’ve got of their now-gone world.

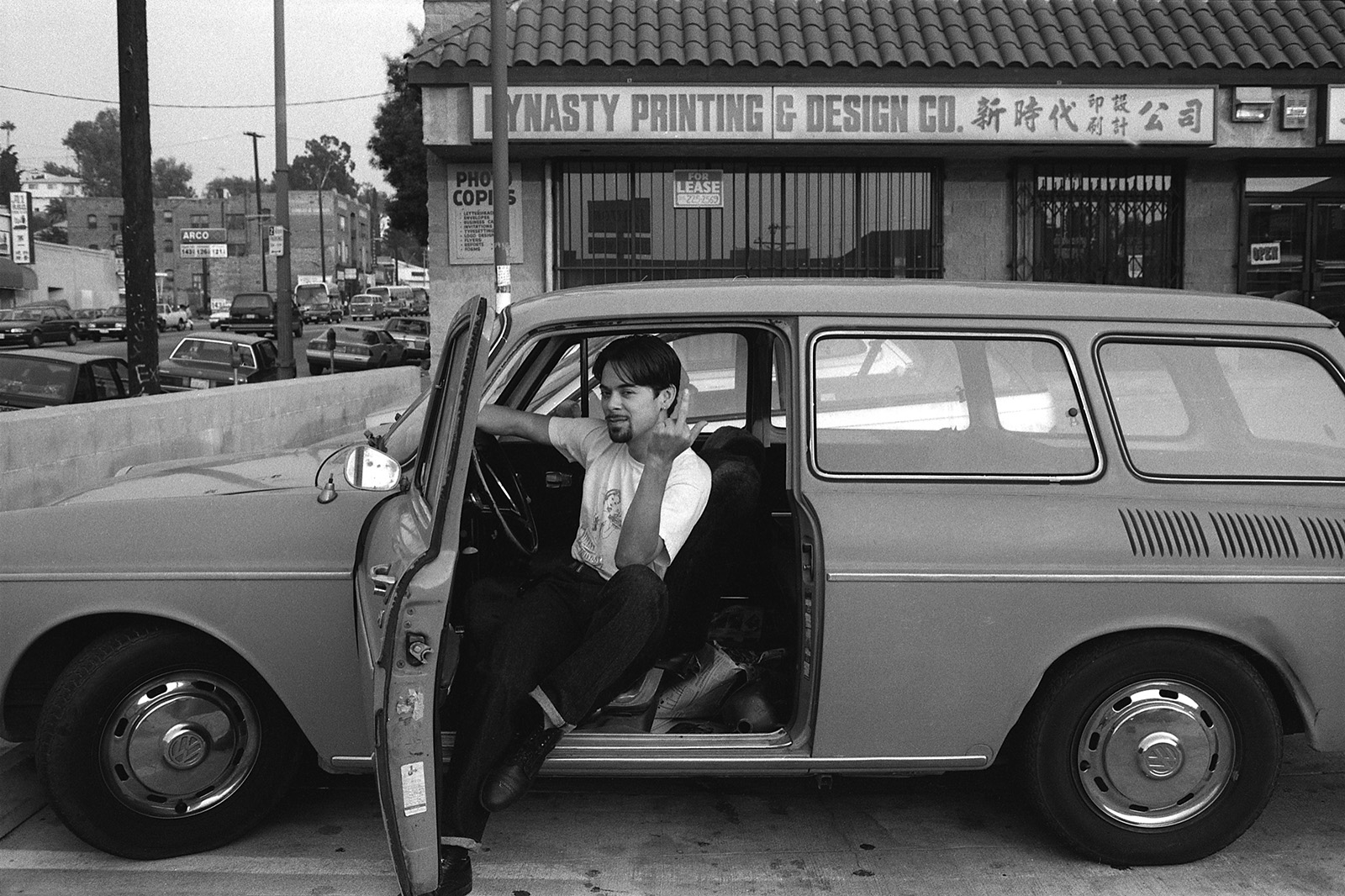

That world was LA in the late eighties and early nineties, a certain east-side/Hollywood, gay/trans, art/punk milieu. I’m sure many remember it well. Many others—newcoming gentrifiers like me—have likely only bothered to learn the basics: rent was cheap, parks were cruising spots, and people actually used to read the LA Weekly. It’s a different thing to get a proper glimpse, to feel you’re flanking Rivera as he prowls Echo Park house parties or lingers in the corners of dingy dressing rooms at Latino drag bars, bestowing big bursts of his camera’s flash whenever the whim strikes. There’s Miss Alex—you’ll learn—and Tatiana, Tina and Paquita, Olga, Gloria, Melissa and Montenegro. There’s La Plaza on La Brea, Le Bar on Glendale, Silverlake Lounge on Sunset, and Mugy’s at Hollywood and Western in the heart of Thai Town.

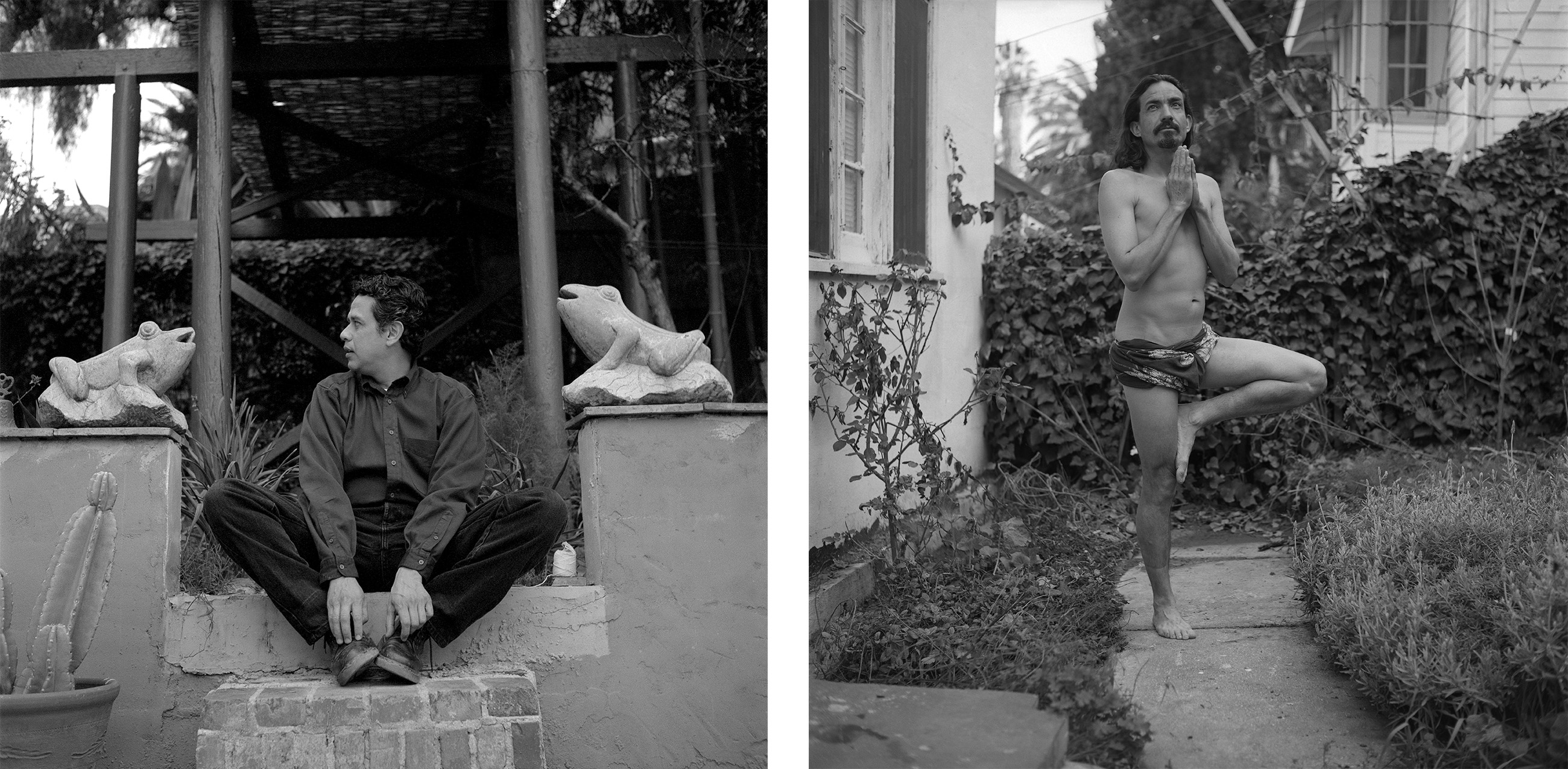

Left: Reynaldo Rivera, Roberto Gil de Montes, Echo Park, 1995. Silver gelatin print, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist. Right: Reynaldo Rivera, Francesco Siqueiros, Echo Park, 1993. Silver gelatin print, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

I use the term Latino because Rivera and Davis both do; ditto Luis Bauz and Chris Kraus in their respective essays. Say what you will—language, in these texts, is not squabbled over, nor is it ever squeaky clean. Call it historical accuracy, if that helps. Rivera’s book comes to us from a land before Latinx. “It wasn’t a matter of transvestite or transgender,” Rivera explains, as quoted by Kraus. “In those days, everyone was a transvestite. There was no variant.” He adds: “It seems like the majority of the performers were transgender, because most of them lived as women, or as much as they could.”

How everyone—I love the way Rivera uses that word—lived, as much as they could, is the true crux of this book. It doesn’t care to compile a tidy chronicle out of an untidy time. It doesn’t index its key players or tamp down its dates. Hard and fast, cemented facts are beside the point. Here instead are pictures taken of friends, by friends, with stories unfurled, first and foremost, for each other. Bygone parties and places and people slowly get put back together, anecdote by anecdote, like exquisite (nay, fabulous) corpses. Rivera tended to capture his coterie as they chose to live, and within the personas they chose to give, as women or otherwise. In many of his photographs, drag performers lean into dusty makeup mirrors, adjusting outfits and fixing hair, or simply posing for themselves, casting an eye on their own creation. Elsewhere, friends embrace and smile for the camera in cramped bar bathrooms and apartment kitchens, drinking and laughing, eternalized in their high spirits. There are concerts and birthday parties and plenty of other occasions to arrive in costume. Everything happens inside and after dark. Daytime, and day jobs, don’t tend to afford the same freedoms.

Reynaldo Rivera, Self-Portrait, Echo Park, 1989. Silver gelatin print, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

As for day jobs, “Rivera thinks he started picking cherries,” writes Kraus in the book’s opening essay, “when he was 12 or 13.” Longtime friends, Kraus recounts Rivera’s early life with particular devotion. It’s a gritty, rousing read. The artist spent much of his childhood on the road with his father, who shuttled between seasonal jobs at a cherry orchard in Stockton and a Campbell’s cannery in the San Joaquin Valley. There was also less official business “fencing stolen merchandise” back in LA. At fourteen, Rivera cashiered at the liquor store his father had bought in Puerto Nuevo, Mexico, until his father shot a prominent gang member and they both had to flee. Rivera was homeless for weeks. At fifteen, Rivera lied about his age and got a union job at the cannery, which gave him his first taste of financial freedom. One of his first purchases was a camera.

Rivera worked seven days a week during the summer months but spent the rest of the year mingling in LA, entrée’d to a new world of clubs and cocaine and creative people by his glamorous cousin Tricia. He got a job as a janitor at the LA Weekly offices and started selling his photos of local fashion shows and concerts to the paper. A few years later, he and his two sisters rented a house on Laguna Avenue, right across from Echo Park Lake. It became a social hub, “one of LA’s most cosmopolitan salons,” according to Kraus. The siblings threw “movie nights, discussions, dinners, Halloween galas and holiday parties” on a regular basis. Rivera took pictures of everyone and everything, determined to capture evidence of a life he had, at last, chosen.

“I still remember the intoxicating smell of stale gym socks and poppers,” writes Davis, waxing sentimental about an old bath house. “Dialogues” between artists can be dry affairs, but the thirty-eight-message exchange between Rivera and Davis is a mesmerizing, miraculous document. The two friends shirk any sort of performed inquiry into their respective practices, enduring motifs, bodies of work. Instead, they speak first and foremost as friends, and as two stewards of an old scene that has since vanished from sight. It is equal parts dishy, uproarious, confessional, and doleful, a rally of remember-whens.

Reynaldo Rivera, Tatiana Volty, Silverlake Lounge, 1986. Silver gelatin print from fire-damaged negative, dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist.

“We got the volk who’d been thrown out of prison by Castro—do you remember the Marielitos?” writes Rivera. “I remember Jay Levin, the publisher of LA Weekly, giving drugs to the staff,” writes Davis. “I remember when the Frog Pond closed because the owner hung himself after finding out he had AIDS.” (Rivera.) “I remember seeing Robert Reed at Numbers. I couldn’t believe Mr. Brady of The Brady Bunch was a big gay letch.” (Davis.) “I remember being at parties in the Mission during the ’70s. I was treated like royalty then because I was a cholo from LA.” (Rivera.) “Do you remember this butch Latina lesbian named Maria Dumbdumb who circulated in and around the punk scene?” (Davis.) “I always wondered what happened to her. She was a handsome dyke with a great sense of style.”

What happened is always a harder question. Rivera doesn’t respond. His photographs preserve his people in their prime, a community flowering at midnight. Inside the old apartments and now-shuttered clubs, there’s never a glance out the window at the oncoming daylight, the dawn of a city of someone else’s creation. x

Juliana Halpert is an artist and writer living in Los Angeles. Her writing has appeared in Bookforum, Frieze, Art in America, and on Artforum.com.