Paige K. B. First Republic Bank Eagle working sample, 2019. Embroidery on silk organza, 2 x 6 in. Courtesy of the artist.

It all started last year with a little in-joke: Make a work for Documenta 13. Never mind that it had closed six years ago. Never mind that no one gave me the nod. I thought I’d turn “Nevertheless, she persisted,” into “Regardless, the artist is proceeding with their production schedule.” With a great team (it me), we’re now producing a line of real fakes, small-batch. Our commitment to the bit is unwavering. You’re probably wondering how we got here.

Last September, I wrote an essay on Flannery Silva, an artist who makes covers, à la cover songs. On these slippery terms, I wanted to consider a method with antecedents in a pre-Copyright Act of ’76 approach to creation that one might call “folk.” Covers don’t tend to come up either in current conversations around cultural appropriation or the discourse stemming from appropriation art. I cited appending, updating, off-roading, enveloping, and overwriting as responsive techniques for dealing with the “gray veil,” that undemocratic, surreal bombardment of information and culture, which you, on the internet reading this, must know well. I was curious as to how one might ghost a personal narrative, replacing it with a structural one. A cover renders “I,” “you,” “he,” “she”; “now,” and “then” interchangeable, like so many knobs to futz with, pitch shifting what’s already there. It’s a light garment for revealing an underlying mask, the protection of which might allow one to say something accurate and true, if honesty isn’t possible. I was fed up with artists and writers being tied, like performers contracted for scripted reality shows, to the impossible stakes of revelation, veracity, or confession—particularly the gendered assumptions of the latter, and all the guilt that word implies. “A real artist is someone who can make a cover their own,” I wrote. “Poor imitators just create original forgettables.” But who has the freedom to be oblique, ambiguous, or even to say nothing at all?

Paige K. B., Pussy Writes a Letter, as Praxis (No Red Light just thin white to thick white like no gaze just glare) via S/S12 Folklore Where “I” Am Just a Filter J/K JK It’s Only SP My D.A.D.A. Squid But the Exhibition Is Not Over When the Show in Kassel Closes ca. The One With the Mike Kelley Cover No Tambourine or Wurlitzer May 2012 AF and Shoutout to Agnes Richter While This Is My Cover Now and Praise Be That At Least It’s Not Original, 2018-2019. Embroidery on silk organza with metal charm, approximately 36 x 24 in. Detail. Courtesy of the artist.

Then, that November, I happened to receive an assignment to interview Seth Price. I was doing my usual level of research beforehand and got snagged on a body of work from his recent past: “Folklore U.S.” Said work comprised a series of sculptures along with a military-inspired fashion collection designed in collaboration with Tim Hamilton and shown in a parking garage in Kassel on June 7, 2012, for the opening of Documenta 13, with the clothes thereafter available for sale in a nearby department store. Both the sculptures and the clothes started from riffs on a standard white security envelope, the interior patterns of which are meant to obscure and protect the ostensibly valuable information within. The garments—a bomber, a batwing sniper jacket—were made of heavy, opaque canvas and lined with logos for the FDIC, Capital One, UBS, an image rights agency, et cetera. Such references (global finance?) were as broad as the shoulders of the models, yet their overall effect was alarmingly specific: white people in Germany stomping around in white clothes with peaked white hoods, spangled with icons of proprietary domination. Price consolidated all these motifs into the assemblage of a kind of tribe, with its charged identity spitting diffusely in the direction of America. Whither folklore, and what of (the) U.S.? Whose ’lore? What folk? The clothes were a meticulous execution of a bit about faux criticality, proposing to subvert the superficial read that “it’s just fashion” in a way that came off as funny, and obnoxious. I also wondered if, now, a white artist could get away with peaked white hoods in any season.

Price and his gallery reasonably indulged my curiosity about this not-very-cornerstone project of his. As it happened, I was already toying with the idea of embroidering excerpts from the writing I had been doing—outside my output for magazines but possibly including some excavations from that oeuvre as well—on white clothes. I wanted to solidify a form for my texts outside the clogged avenues of art criticism and online hot-take posting. I had taken on writing as an artist anyway, and nursed a perfectly healthy desire to cannibalize the professional self I had constructed before it cannibalized moi. Those Price clothes were overloaded, but could they be emptied? My interest wasn’t personally targeted, or splenetic, nor did I want to pay any particular homage. I just saw an option.

By editing down this context into the embroidery of a single handmade garment based on a borrowed form, I imagined I could arrive at a parody of contemporary culture’s habitual and preposterous nostalgia—my fixation isn’t actually my fixation. Anyway, 2012 isn’t long ago enough to be ripe (yet) for ritualistic retreading. When working in the art world, it can seem compulsory to beat on against the current while ceaselessly beating off about the ever more recent past. But to shape one’s future by consciously trying a little bad faith on for size is just how Marcel Broodthaers, for one, got his game on, plunging his potentially unread words into plaster to make the ludicrously illegible Pense-bete, 1964. From the smarminess of that guy toward the audacity of this bitch, a change of tactics can be invigorating. Whether it was a good idea or not seemed beside the point.

Paige K. B., From the desk of PKB [Agnes Richter x Folklore U.S.] VEL VER, 2019. Ink-jet print on vellum, 11 x 8 ½ in. Courtesy of the artist.

In Heidelberg, south of Kassel, there’s the Prinzhorn Collection, where Agnes Richter’s jacket is kept. Richter was a nineteenth-century seamstress who passed her time in an asylum embroidering her outerwear. The writing on it is hardly legible, but the Google Translate version of the museum’s description of the piece assures us, “Very personal things are transferred here to the second skin.” Here is perhaps the worst thing one could say about it, and any female’s writing: Pussy writes a letter. In this narrative I’m assembling, the affiliation with either Price or Richter is—spoiler—a false flag, a by turns facetious and melodramatic cover for some off-roading between canons. In lieu of “I” as subject, this minefield of context will serve.

In the May 2012 issue of Artforum, the one with the Mike Kelley cover, there’s an interview with the artistic director of Documenta 13, Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev. She projects into the future: “It is not over when the exhibition in Kassel closes.” And furthermore: “Not everything is published; not everything finds its way into the historical record and into the realm of what can be proved. And those leaps of imagination, those connections, are constantly happening today, too.” Perhaps I never needed an invitation after all.

Left: Paige K. B., From the desk of PKB (Pussy Writes a Letter…[for dOCUMENTA(13)]) via the Thirteenth Edition of Moi feat. First Republic Eagle, 2019. Colored pencil and carbon copy on ink-jet print on paper, 11 x 8 ½ in. Right: From the desk of PKB (dOCUMENTS like the interview with John Miller from 1991 and tributes from 2012), 2019. Carbon copy, acrylic, and collage on ink-jet print on paper, 11 x 8 ½ in. Courtesy of the artist.

QAnon captures hearts and minds because we know we’re being lied to, catastrophically, all the time. Q is constantly interrogating their audience, after bestowing a crumb or two, with the refrain, “Why is this relevant?” Sometimes the sentence appears multiple times in one post, reflecting back a reader’s own likely query. If American history, including that of its art, can be written via a lineup of scams, schemes, and cover-ups, Q is like an institutional critique artist, inspired by Hans Haacke as much as Donald Rumsfeld. Regardless of whether it’s a false bill of goods, what Q offers sells, because in their hectic, grandiose way they’re articulating a vast contemporary folklore—a real Folklore U.S., if you will. It’s a sweeping legend that makes no sense, compliments of reality.

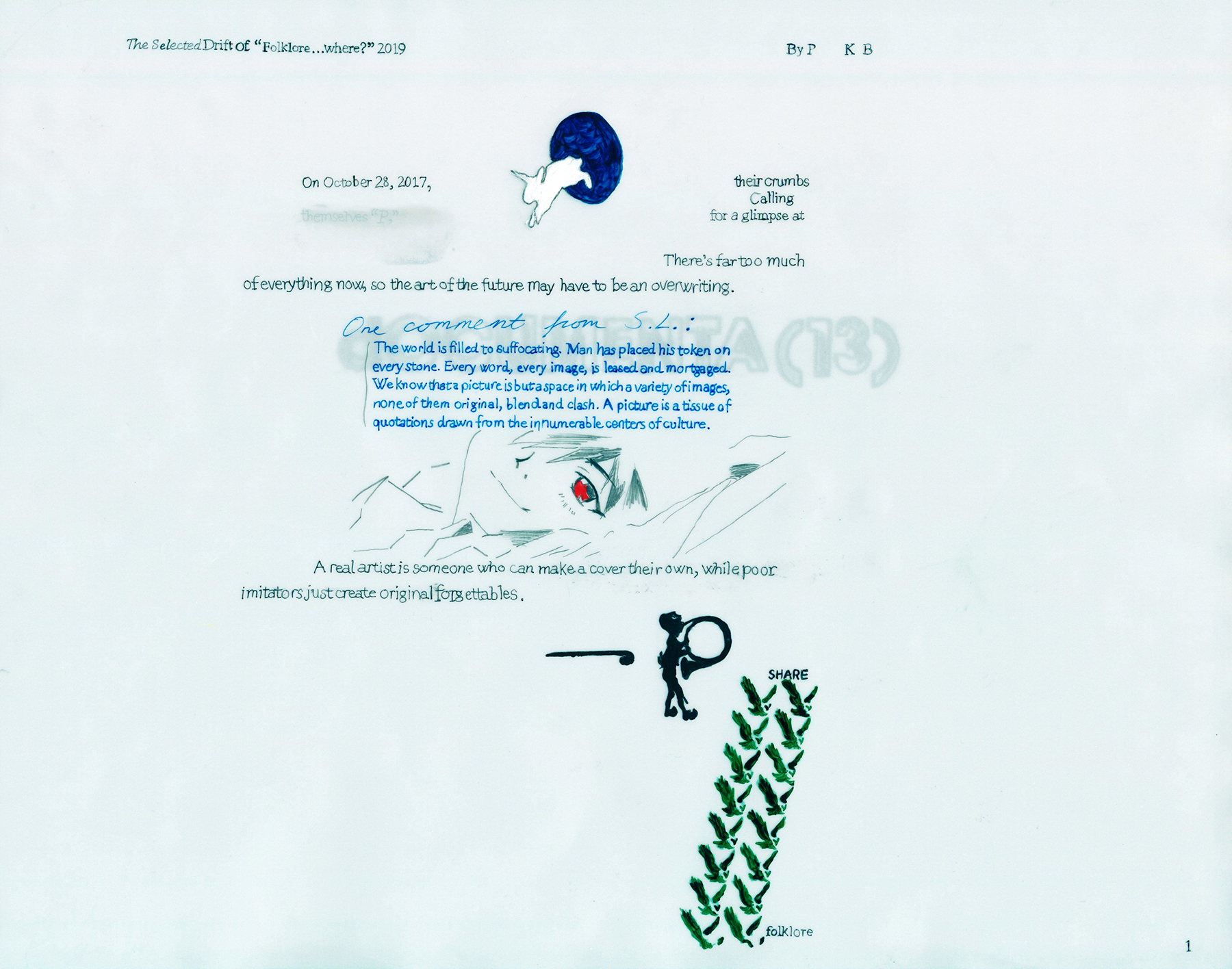

Paige K. B., The Selected Drift of “Folklore…where?” 2019 page 1 cover page, 2019. Pen, ink, egg tempera, gouache, acrylic, graphite, and collage on two sheets of vellum, 11 x 14 in. Courtesy of the artist.

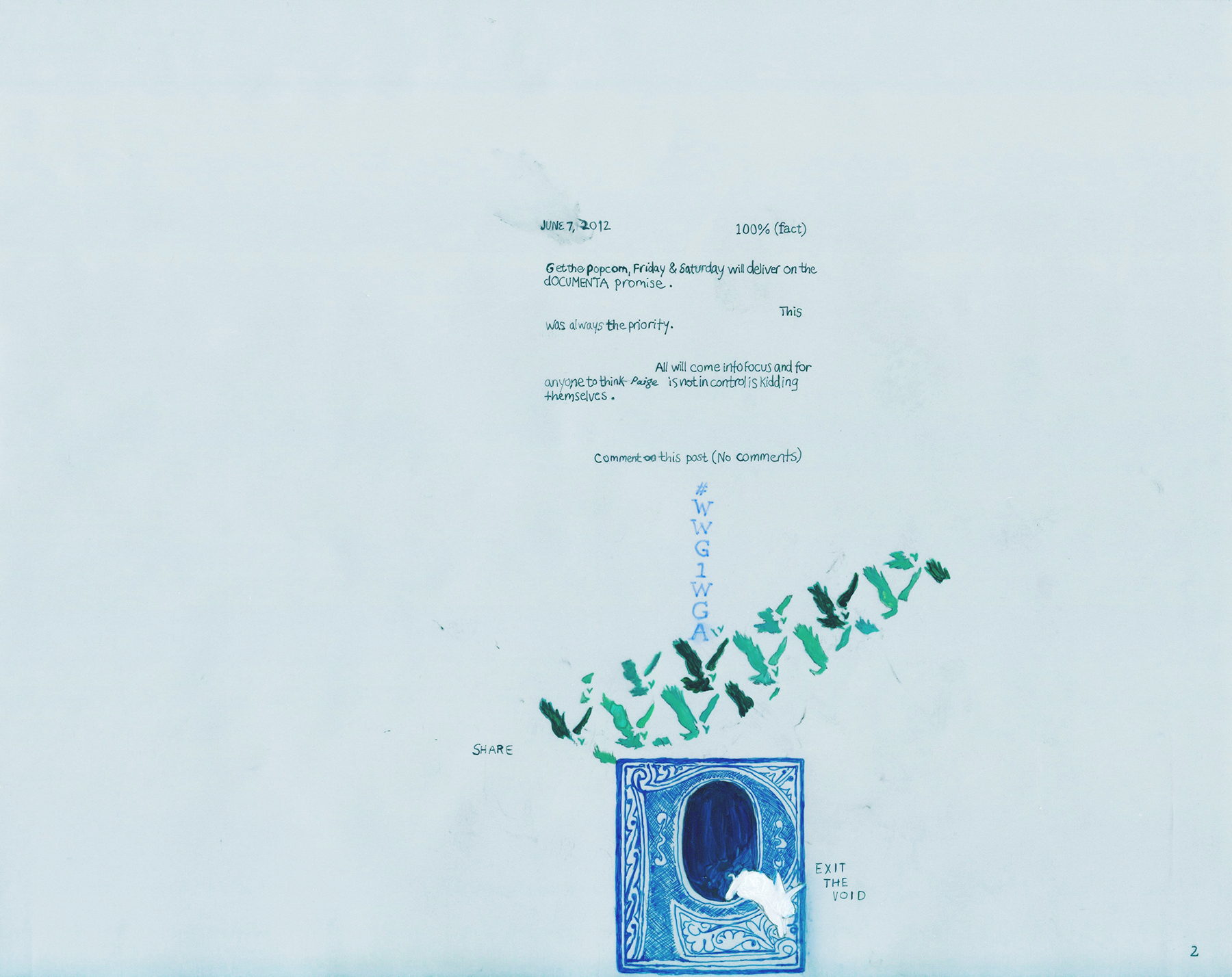

Now, whither my tale, my heroine’s journey in all this? After considering Q’s narrative technique, I began a couple series of drawings to complement the garment; altogether it will eventually, cumulatively be titled “Folklore . . . where?” The first series brings together fragments of critical texts—whether authored by Mike Kelley, Sherrie Levine, Oscar Wilde, or myself—and what people will likely call personal writing, for lack of imagination, along with banal facts sourced from the Wikipedia page for the year 2012. Each excerpt from the series is made by carbon-copying writing and imagery, created anew or borrowed afresh, on scans made this year of printouts from 2001 and 2002 (those being the same years across which the thirteenth edition of Paige K. B. was staged). Q often suggests a game, like chess, or says, “Learn to read the map.” So I, signing the drawings “P” in various fonts, suggest a game of hide and seek. My sources and citations are hiding in plain sight, and my intentions are made clear only through muddying the waters with the additive techniques of conspiracy. P might implore, “Learn to read the map of Mike Kelley’s work better,” or claim, “My gestures have a lineage,” by copying and pasting it in, artisanally. For a second series of drawings, “The Selected Drift of Folklore . . . where?,” I’m rewriting Q’s posts to suit this fungible folklore of mine. One of the earliest drawings is falsely dated June 7, 2012, the date of Price’s Documenta fashion show. For Q’s phrase, “MAGA Promise,” dub in the “dOCUMENTA Promise.” A conspiracy has to start somewhere, but then it can go anywhere. The personal is structural.

Paige K. B., The Selected Drift of “Folklore…where?” 2019 (Get the popcorn…) page 2, 2019. Pen, gouache, acrylic, egg tempera, and carbon copy on vellum, 11 x 14 in. Courtesy of the artist.

For a decade and change, my conscience has been torn between the two poles of Hannah Wilke’s proposal to “make objects instead of being one,” and Douglas Huebler’s mission statement: “The world is full of objects, more or less interesting; I do not wish to add any more.” The world is full of facts, more or less interesting. The world is full of stories. I prefer to fuck with what’s already there. Collage is an inherently conspiratorial technique, and I’m certain that what the artist maintains is just as important as what they create. This is how I synthesize what they taught me and move toward, as Lorraine O’Grady articulated it, a counter-confessional. I have nothing to confess except my right as an artist to work with what’s at hand. I’m transparently covering the solid, like paper covers rock.

“I” is over the hill as a subject, but a myth like that tends to undergird an American’s passage, and that’s a device, a racket to work with. That, and attitude; like Oscar Wilde said in 1885, “In aesthetic criticism attitude is everything.” Like Jack Goldstein declared in a list of aphorisms from 1983, “Presentation is all about attitude,” and, “Art should be a trailer for the future.” Meanwhile, says Q, “Future shows past.” I take them all at their word and give myself the nod. Have faith; trust the plan.

P

Paige K. B. is an artist, writer, former Associate Editor at Artforum, and former Arts Editor at GARAGE. He has written for Artforum, Bookforum, GARAGE, Art in America, SSENSE, and The White Review. Her recent exhibitions include “Routine à la mode” at Kimberly-Klark, “The Unbearable Lightness of Paris / I Know What I Did Last Summer” on Artforum.com, and a performance on Montez Press Radio of their script for “The Selected Crumbs of QAnon.”