November 20 would have marked the 100th birthday of Sister Corita Kent. As a graphic artist, Sister Corita contributed a signature style to the political art of the ’60s. As a bold reformer, she pushed the Church to modernize until breaking with the order in 1968. And so, to celebrate her centenary, we’ve commissioned a group of artists, curators, and admirers to reflect on her work and its influence. Our second contributor to the series is artist Jason Simon, whose thoughts on Sister Corita shaped his recent trip to LA.

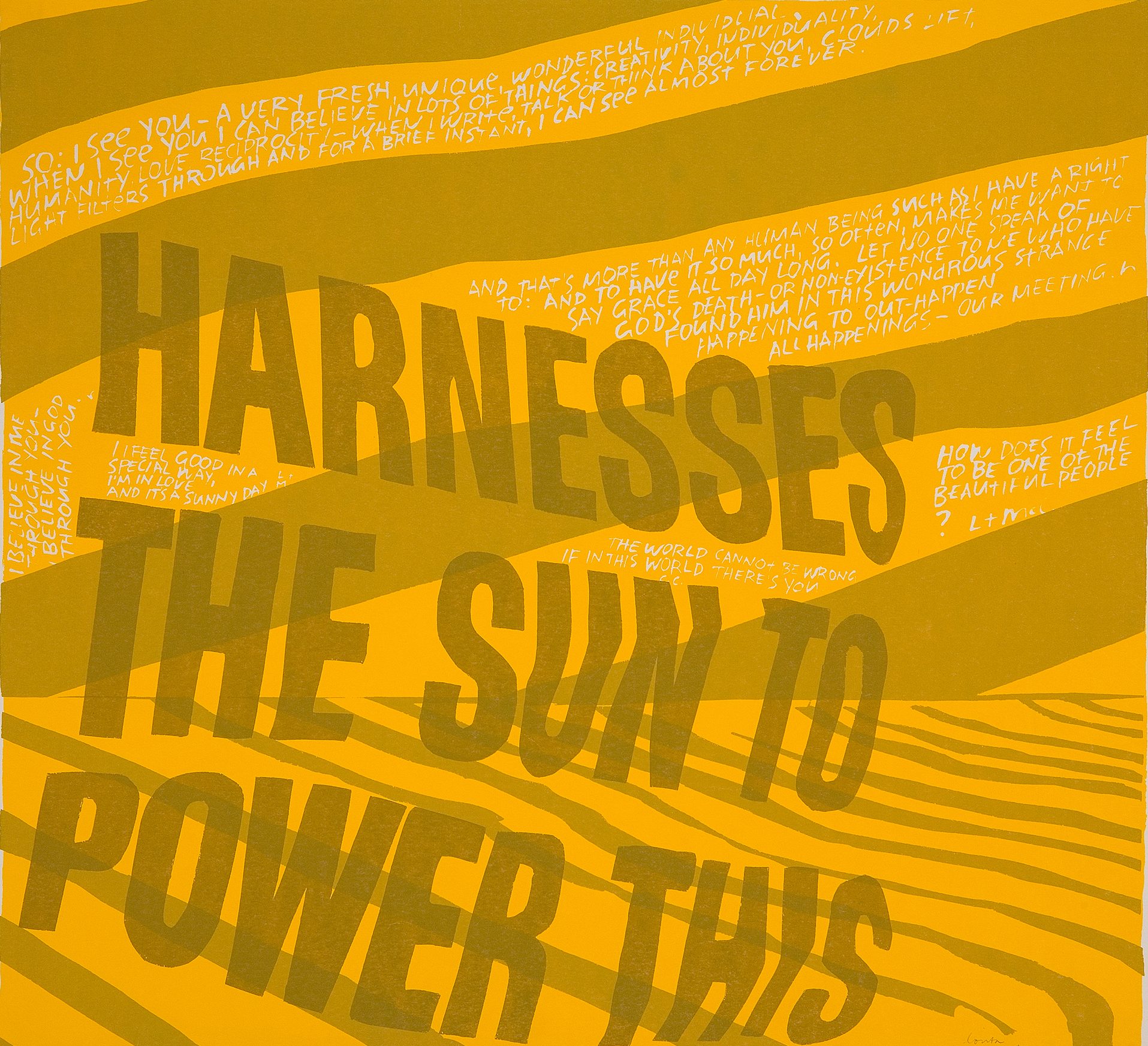

Sister Corita Kent, harness the sun, 1967. Silkscreen on paper. Courtesy of and photo by Liza Johnson.

A couple of weeks ago, I brought my friend Liza Johnson for her first visit to the Corita Art Center at the Immaculate Heart Community in Los Angeles. When Liza moved West from New York last year, I gave her a silk-screened image by Corita, harness the sun (1967), as a kind of California welcome from the East, where I live. I had last visited the Center ten years before, helping the staff and some visiting curators organize the remaining serigraphs into representative groupings. Nothing had changed. Framed prints progressed chronologically from the modest entry corridor to an office and a meeting space that all function as the archive’s permanent exhibition. In that sense, Corita’s work continues to fill the school, and the school continues to envelop her work.

The day before, Liza and I visited the Underground Museum, which was presenting a large exhibition by Deana Lawson. Noah Davis, the museum’s founder, who died in 2015 at the age of 32, had planned the show. His vision and mission for the institution remains in its foreground, much like Sister Corita’s at the Center. Corita and Davis seem to have shared an appreciation of storefronts and the democratic potential of retail. We also went to see James Benning’s show at O-Town House, 31 Friends. The show is a collection of photos Benning requested from people to whom he had gifted artworks. Benning asked the recipients to memorialize the works in their homes with snapshots, and those grouped photos comprised the show at O-Town. (The gallerist, Scott Cameron Weaver, is going to Rome soon, for a show curated by Marta Fontolan he helped organize called say ahh… at Indipendenza Roma that includes, coincidentally, works by Sister Corita, alongside works by LA artists Larry Johnson and Adam Stamp.) The Center, The Underground, and O-Town are all free and open to the public. At each venue I purchased books and gifts.

These visits were all secondary to the event that brought me to LA. I was there to introduce a film series I curated to accompany the exhibition One Day At A Time, at MOCA, a group show about shared affinities with the painter and writer Manny Farber. I had been Manny’s teaching assistant at the University of California, San Diego some 30 years before, and I organized the film series along the lines of resurrected memories and fond ideas from among the efforts of kindred artists. In order to construct curatorial associations among these films and videos, mostly made in the intervening decades, I indulged a feeling of never having left that school, and of being enveloped by it since. Not such a stretch, it turns out, but privately I doubted that saying so in person was reason enough to cross the country twice in four days. The films held up well on their own.

Liza was not the first friend to move west from New York and receive a Corita from me as a bit of repatriation via house warming. Andrea Fraser also got one, (give the gang) the clue is in the signs (1966). It was Andrea’s essay in X-TRA, “Toward a Reflexive Resistance,” that I first read when I got back to New York. In brief, Fraser makes an urgent claim that Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of the field of power might help us understand the bizarre contradictions that produced this political moment, and to navigate these dark times.

Sister Corita Kent, harness the sun, 1967. Silkscreen on paper. Courtesy of the Corita Art Center, Immaculate Heart Community, Los Angeles.

Taking in Andrea’s disquisition, my head was still full of Corita and Davis and Farber and Benning’s Los Angeles, and so, jet lagged, I combined them all. Operating in modest storefronts, teaching and gifting, often privileging a non-specialist audience, without ideological presumption, they are or were artists practicing a kind of reflexive resistance, including Fraser herself, I wager. And, despite Fraser’s assessment of the centers of power, they might demonstrate just how available reflexive resistance for artists can be. Fraser reminds us that reflexivity, like mindfulness, can be a far cry from oppositional; and amidst active oppositional politics, reflexivity is the tall order that prompted her essay in the first place. But among artists, reflexive resistance, like feminism, can also be workaday, incorporated and put to functional use as a matter of course in the process of giving form to ideas. It’s the damned dizzyingly urgent expectation of it that is so out of whack. What sort of art practice might a reflexive resistance accompany, even now? Fraser, wisely, leaves the question unasked and unanswered. Less wisely, I imagine: a practice that would not be normative, and probably not too remunerative. And for the great majority of artists, to whom it might apply in their daily lives, the practice would be teachable, local, available, with its own attendant publishing and event culture, produced in affordable spaces; idea driven, and sociable. Which is, more or less, what I saw in LA.

–Jason Simon, November 2018

Jason Simon is an artist who lives and works in New York. His writing has appeared in Artforum, Parkett, and Frieze, among others. From 2005 to 2008, he was a founding member of the collectively run New York gallery Orchard.