Nancy Holt, Electrical System, 1982. 3/4 in. steel conduit, lighting and electrical fixtures, light bulbs, electrical wire, dimensions variable. Installation view, Nancy Holt: Locating Perception, Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles, October 28, 2022—January 14, 2023. Photo: Robert Wedemeyer.

Nancy Holt’s room-sized sculptural installation Electrical System consists of repeating units of arcing electrical conduit punctuated at regular intervals by bare, incandescent bulbs, their pronounced spherical forms evocative of Edison’s original design. The illuminated grid resembles a scale architectural model. Meandering through it, with no other light in the room, I admit to feeling a certain sense of wonderment at seeing these common fixtures of the built environment rendered unfamiliar.

Nancy Holt, Electrical System II: Bellman Circuit, 1982. Installation view, David Bellman Gallery, Toronto, Canada. 3/4 in. steel conduit, lighting and electrical fixtures, light bulbs, electrical wire, dimensions variable. Courtesy of Sprüth Magers. © Holt/Smithson Foundation. Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York.

First shown in 1982, Electrical System has been recreated for Holt’s solo exhibition, Locating Perception, at Sprüth Magers, Los Angeles. The piece is one of a series of “System Works” Holt began in the 1980s following her landmark piece Sun Tunnels (1973–76), four open concrete cylinders in the Utah desert positioned to align with the sun during the summer and winter solstices. Sun Tunnels and other works from around this time, such as Hydra’s Head (1974), a configuration of six concrete pools along a bank of the Niagara River, are often discussed in phenomenological terms, as inquiries into vision and perception. There is a certain continuity between the way these works act as framing devices for light or astronomical events and how, in her “System Works,” Holt conceived of human technological systems as channeling natural elements.

Nancy Holt, Sun Tunnels, 1973-76. Concrete; total length: 86 ft.; tunnel length: 18 ft.; tunnel diameters outside: 9 ft. 2-1/2 in.; tunnel diameters inside: 8 ft.; wall thickness: 7 1/2 in. Great Basin Desert, Utah. The tunnels are aligned with the sun on the horizon (the sunrises and sunsets) on the solstices. Each tunnel has a different configuration of holes corresponding to stars in four constellations: Draco, Perseus, Columba, Capricorn. Collection of the Dia Art Foundation with support from Holt/Smithson Foundation. © Holt/Smithson Foundation and Dia Art Foundation. Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York.

In contrast to these earlier works, however, Holt’s System Works take manmade utility systems—plumbing, electricity, drainage, heating, gas, and ventilation—as their subject, treating the standard materials of each system formally, as sculptures. In each piece in the series, a different system’s pipes bend and loop inefficiently across the gallery they’re shown in, and in some cases even extend out a window and onto an adjacent lawn. Their conspicuousness as sculptures only underscores the degree to which these systems are taken for granted in daily life whenever we switch on a lightbulb or turn on a faucet.

Nancy Holt, Hydra’s Head, 1974. Concrete, water, earth; 28 x 62 ft.; pool diameters: two 4 ft., three 3 ft., one 2 ft.; depths: 3 ft.; water volume: 1340 gallons. Positions and sizes of pools based on stars in the head of the constellation, Hydra. Courtesy of Sprüth Magers. © Holt/Smithson Foundation. Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York.

These works have a particular resonance considered from Los Angeles on the heels of a summer of water restrictions, record high gas prices, and pleas to limit electricity usage emblazoned on marquees overhanging the freeway. In the late 1970s and ’80s, there were similar concerns over resource scarcity and volatility in the energy sector. Twice in the 1970s, Americans saw steep inflation in gas prices due to military conflicts in the Middle East and a resulting OPEC embargo. This prompted the US to build the Trans-Alaska Pipeline, completed in 1977, to reduce dependence on foreign oil.

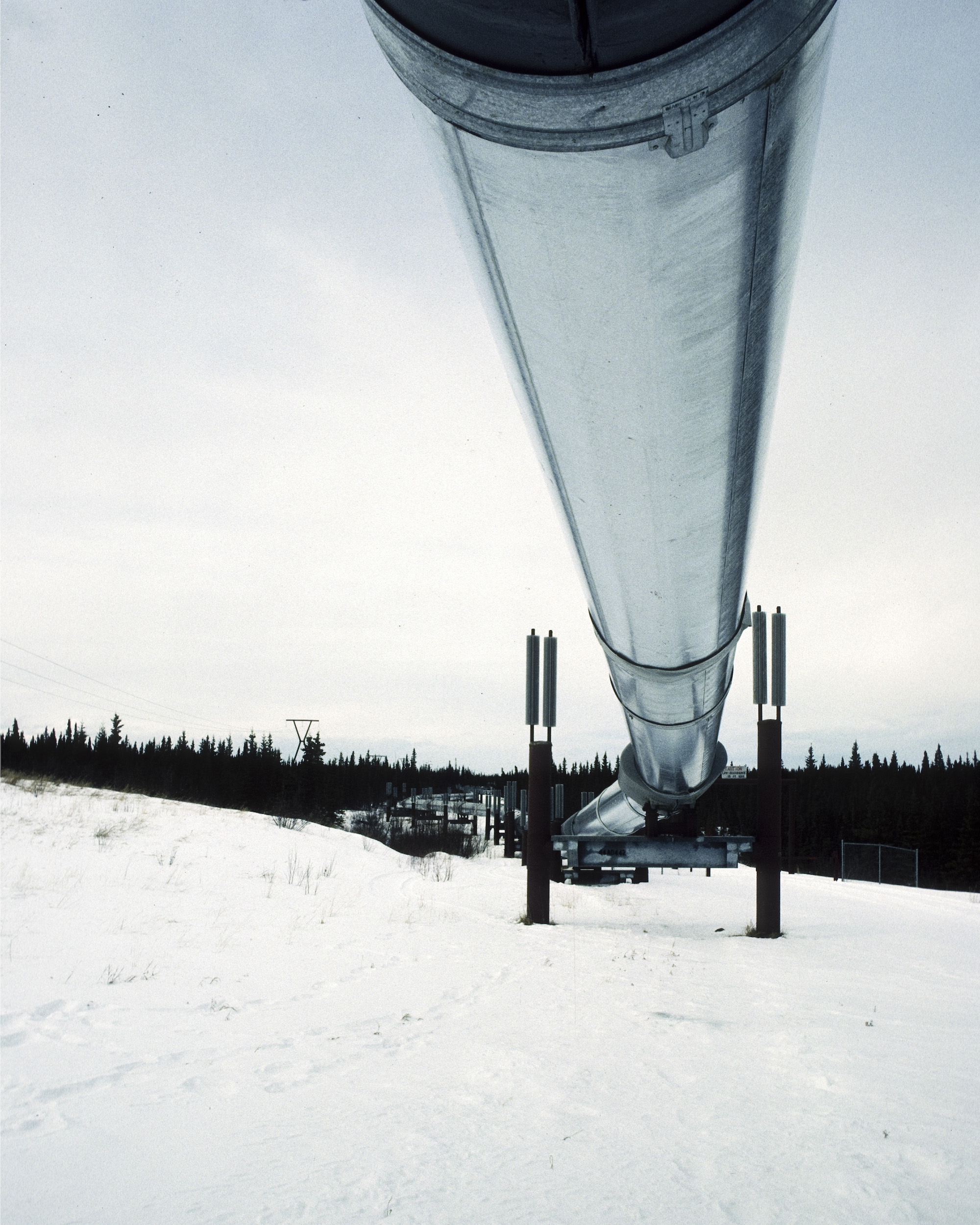

View of the Trans-Alaska Pipeline in 1986. © Holt/Smithson Foundation. Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York. Photo: Nancy Holt.

Holt had the opportunity to visit the Trans-Alaska Pipeline in 1986 while in Anchorage at the invitation of the Visual Arts Center, an institution partially endowed by an Alaskan oil company. She photographed the pipeline and produced one of her most overtly political works in response, aptly titled Pipeline I. The work consisted of metal piping that wound its way from the Center’s exterior through its indoor gallery space, and seemingly disappeared into the floor, but not before leaking a small pool of oil onto a white museum plinth, a reference to the seepages Holt witnessed from cracked and rusted segments of the pipeline when she visited.

Nancy Holt, Pipeline, 1986. Steel, oil, 30 x 32 x 15 ft. (indoor section); 26 x 15 x 6 ft. (outdoor section #1); 10 x 31 x 18 ft. (outdoor section #2), steel duct 1 ft. (30.5 cm) diameter. Installation view, Visual Arts Center of Alaska, Anchorage. © Holt/Smithson Foundation. Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York.

This work (and its second iteration, presented at the Fairbanks Arts Association later that year) implicates geopolitical conditions in their commentary on the environmental impacts of the pipeline. They are as much about foreign affairs and President Reagan’s deregulatory economic policies, signed into law in 1981, as they are about leaky infrastructure. In a similar way, as functional sculptures, the other works in the series presuppose a certain set of conditions that allow utility systems to function—for instance, political and economic stability, intact municipal governance, and predictable weather patterns.

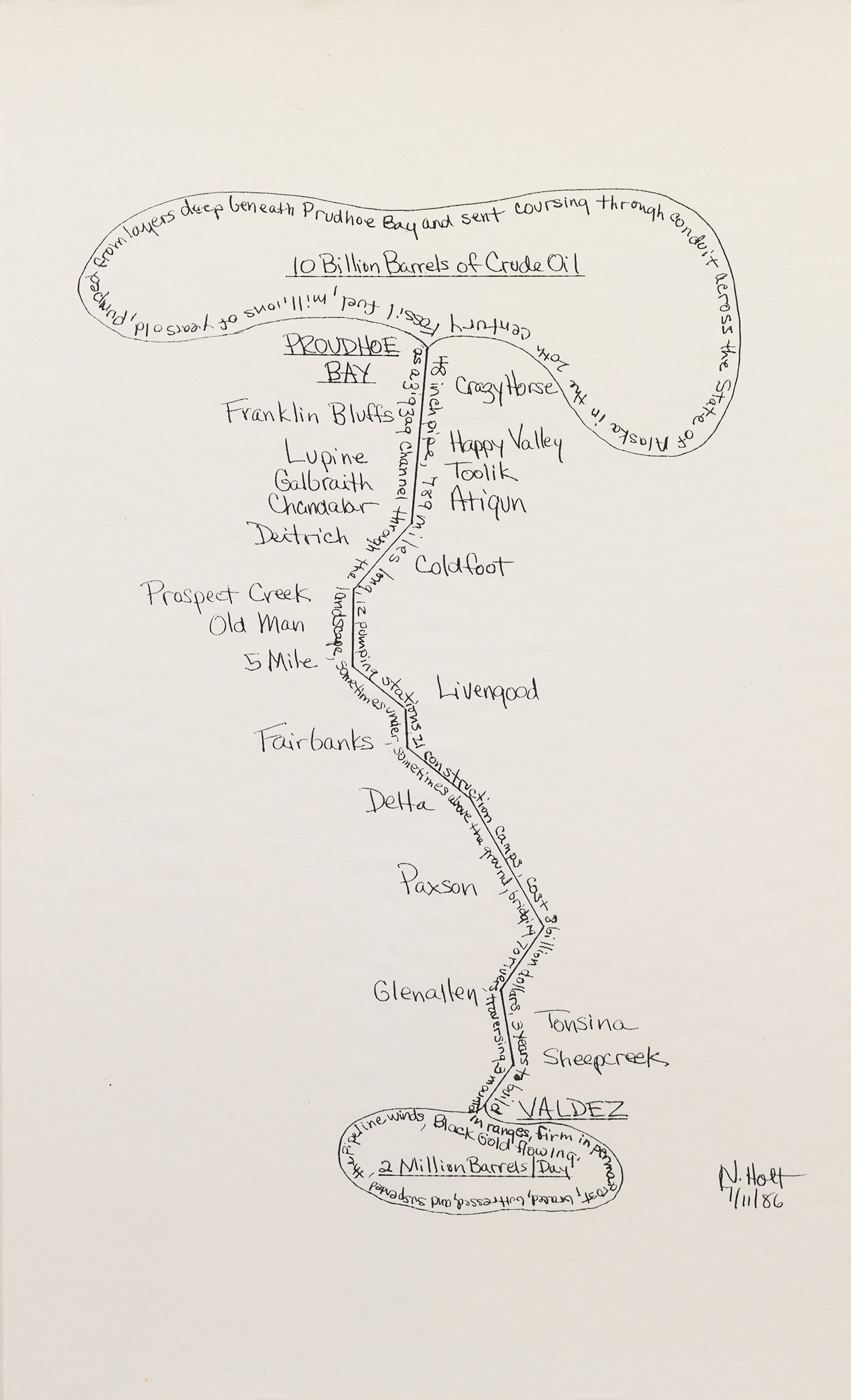

Nancy Holt, 10 Billion Barrels of Crude Oil, 1986. Ink on paper, 14 x 8 1/2 in. © Holt/Smithson Foundation. Licensed by Artists Rights Society, New York.

The electrical grid, theorist Jane Bennett writes in Vibrant Matter (2010), can be understood “as a volatile mix of coal, sweat, electromagnetic fields, computer programs, electron streams, profit motives, heat, lifestyles, nuclear fuel, plastic, fantasies of mastery, static, legislation, water, economic theory, wire, and wood—to name just some of the actants.” In keeping with this idea, and in contrast to the emphasis on repetition and regularity in much of the systems art of her peers, Holt’s formal treatment of systems as mutable and malleable points to their underlying volatility. These works widen the lens on the systems that shape our lives, showing them to be dynamic assemblages, produced and upheld by human and nonhuman actants. Though often stable, they remain unfixed. x

Hannah Spears is a curator and writer living in Los Angeles.