Strip malls, reality television, casinos, message boards—even art, lots of it—can be mindless and full of pleasure. Keith J. Varadi met Scott Benzel at Bel Ami in Los Angeles to speak about his exhibition, Mindless Pleasures, on view August 1–October 3, 2020. Benzel’s sculptures, assemblies of collectors’ items ranging from meteorite fragments to a Mallarmé folio, offer meditations on chance, fate, and cultural detritus. Little wonder they wound up discussing the artist’s hometown, Las Vegas, at great length.

Scott Benzel, Hybrid Monte Carlo, 2020. Regulation roulette wheel, regulation “pin,” contact mic, motion detector, oscilloscopes, analog electronic circuits based on the equations of Henri Poincaré and Edward Lorenz (top: Lorenz “owl face,” middle: Poincaré diagram, bottom: Poincaré-derived RC “chaos ladder”), circuits by AST, 73 x 20 x 41 in. Installation view, Mindless Pleasures, Bel Ami, Los Angeles, August 1–October 3, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Bel Ami, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

KEITH J. VARADI: The title of this exhibition refers to Thomas Pynchon’s discarded title for what would become Gravity’s Rainbow (1973). The novel takes place at the end of World War II; this exhibition has been mounted towards the end of Donald Trump’s first (and hopefully only) term as president. Would you mind talking about how you have, as far as I can tell, used these moments as bookends?

SCOTT BENZEL: Prior to his career as a novelist, Pynchon was in the Navy and then worked at Boeing, writing rocketry manuals. He was aware that the Space Race and the military-industrial complex had their roots in the Nazi V-2 rocket program, just as the American Dream had its roots in military adventurism, oil imperialism, CIA coups, and other shenanigans. Mindless pleasures distract from the deadly serious business of doing business. The casino, for example—a locus of distraction, a bacchanal or potlatch, and a model for hyper-capitalism, indulging greed, abstract or real violence, unchecked growth—has engulfed the social, the carnivalesque has invaded the halls of power, and the clowns now determine our fate.

KJV: Wow, yes, okay. Something I noticed right away is this show’s archival vibe. Artifacts like these Janus head cartouches on glass and chicken wire, or this physical Dogecoin, and outmoded technology like these vintage oscilloscopes, are presented in a manner that might be confusing to the casual viewer seeking automatic returns on their time—conditioned by the watered-down culture of the Museum of Ice Cream, for example, or the disinformation spoon-fed to people on both the left and the right via scream segments. But here, you have generously placed faith in the viewer—you have curated items from disparate times, people, and places, and given us space to make sense of the arrangements.

SB: A major theme of the show is “time,” so yes, I’m folding a lot of times and theories of time together. The figures on the three stacked oscilloscopes in Hybrid Monte Carlo (2020) are visualizations of algorithms formulated at different times but feeding into one another, both historically and electronically, via integrated circuits—a Lorenz “owl face” from the late twentieth century feeds into a Poincaré diagram from the late nineteenth century and a mid-twentieth century RC “chaos ladder” that’s based on Henri Poincaré’s equations. They are all modulated by the action of a roulette wheel, a device that inspired Poincaré’s solution to the three-body problem and gave birth to what we now call chaos or complexity theory.

KJV: So when the viewer spins the wheel, they are activating some sort of complex chaos?

SB: Yes, there are two inputs from the wheel that gauge the speed of rotation and the velocity and end state of the “pin” or ball. These data are input into three circuits that also cascade into and interact with one another. Visually, this translates into the Lorenz owl face becoming more animated and agitated, the Poincaré diagram spinning across the oscilloscope and then stopping abruptly, and the RC ladder stretching like a rubber band.

Scott Benzel, California Split / La Fourchette du Cavalier (details and installation view), 2020. Modified Artemide lamp, modified lamp by unknown Italian designer, oscilloscope, analog electronic circuits based on the equations of Hermann Minkowski and Edward Lorenz, modified California Split film poster, Minkowski spacetime diagram, Poincaré diagrams from New Methods of Celestial Mechanics, chicken wire, circuits by AST, dimensions variable. Courtesy the artist and Bel Ami, Los Angeles. Photos: Paul Salveson.

And in California Split / La Fourchette du Cavalier (2020), the shapes of the two household lamps on top of the oscilloscope suggest Hermann Minkowski’s original diagram of spacetime from 1908. The lamps are programmed to reproduce his equation and feed into another Lorenz diagram on the oscilloscope via a photovoltaic cell. Minkowski’s spacetime diagram posits a “block universe,” in which all time and all space exist as a single block, occurring simultaneously, eliminating chance and free will. So, as a kind of counterpoint, the Janus head cartouches, chicken wire, and glass, on the long shelf in Mindless Pleasures (‘Shuffled my mind, came up with a better hand’) (2020), are a sort of game based on John Conway’s Game of Life in which an agent called Janus progresses through a system of hexagons, conducting quantum spin experiments, and “proves” the existence of free will—and when I say proves, I mean, it’s a thought experiment, and free will is not technically proven…

KJV: So chance and free will: is it one or the other? I mean, are they at odds with each other? Do we have a chance at free will?

SB: That’s the question with Minkowski’s and Einstein’s related conceptions of spacetime: if relativity exists, if past, present, and future are all real and extant, how do free will or chance exist? The “block universe” that they posit seems to rule out chance. However, in the century since they shared their work on these questions, a number of cosmologists, physicists, and mathematicians have put forward different concepts of spacetime, including an “evolving block universe” and “accretive time,” that are largely compatible with relativity and other elements of spacetime but allow for becoming and chance.

Scott Benzel, Mindless Pleasures (‘Shuffled my mind, came up with a better hand’), 2020. Shelf with prehistoric insect preserved in Baltic amber circa 40 million BCE, lucky hand root (salep), Roman Janus head coin circa 30–40 BCE, Campo del Cielo meteorite fragment, modified cowrie shells, mandrake root, polished obsidian, Stardust Resort and Casino regulation casino playing card deck, Helmholz resonator, Klein bottle, modified Marcel Duchamp Rotoreliefs (Koenig edition), Janus head cartouches, glass, chicken wire, 6 x 78 x 6 in. Detail showing Janus head cartouches and Duchamp Rotoreliefs. Courtesy the artist and Bel Ami, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

KJV: But let’s back up a minute. We first met on the way to Las Vegas. And, as you were driving us into the desert, I became increasingly confused as to why you were going there, because you seemed to loathe this culture that I love. I mean, love is a strong word—there are all sorts of tragedies to witness in that city, but there’s nothing like the whole American spectacle laid out in one small, shocking, but somehow serene landscape. Vegas is like a public Biosphere 2, and you can sort of witness…

SB: Accelerated capitalism?

KJV: I mean, is this an absurd analogy?

SB: No, I think it makes total sense. There’s an attraction-repulsion thing going on, for sure. I think what you’re talking about has more to do with marketing—today, the city is marketed in this slightly naughty, “What Happens in Vegas, Stays in Vegas” way, but more for the wider middle class. I mean, it is definitely more family-friendly now than it once was. You can make bad decisions without feeling like you might get knifed in an alleyway. These places started springing up, like the Luxor, the Paris, the Venetian. The Luxor, in particular—I can’t quite wrap my head around it. When I was there, taking these silver gelatin photographs hanging on the wall [Stele; Pylon; Luxor, Las Vegas (2020)], I actually stayed in the hotel, on the inside of this pyramid. It was like sleeping in an attic, you know, with the angled walls. Vegas is like this boiling, bubbling cauldron of myth. And it’s not healthy, necessarily. But it’s also infectious.

Scott Benzel, Luxor, Las Vegas, 2020. Gelatin silver print, 22 x 26 in. (framed). Edition 1 of 3 + 1 AP. Courtesy the artist and Bel Ami, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

KJV: Yeah. I wonder how many people go to Vegas and they’re like, “I saw the Eiffel Tower. I don’t really need to go to Paris.” You know? “I went to the Venetian, I got in the paddle boats.” And you’re like, “Those aren’t paddle boats, man. And that’s not Venice.”

SB: Right. What’s authentic? You know, I honestly don’t know how much of this was mythmaking, but the story is that J. G. Ballard very happily lived this mainstream suburban existence, but then wrote these incredibly violent and atavistic revenge fantasies on the culture. I think there’s something to that.

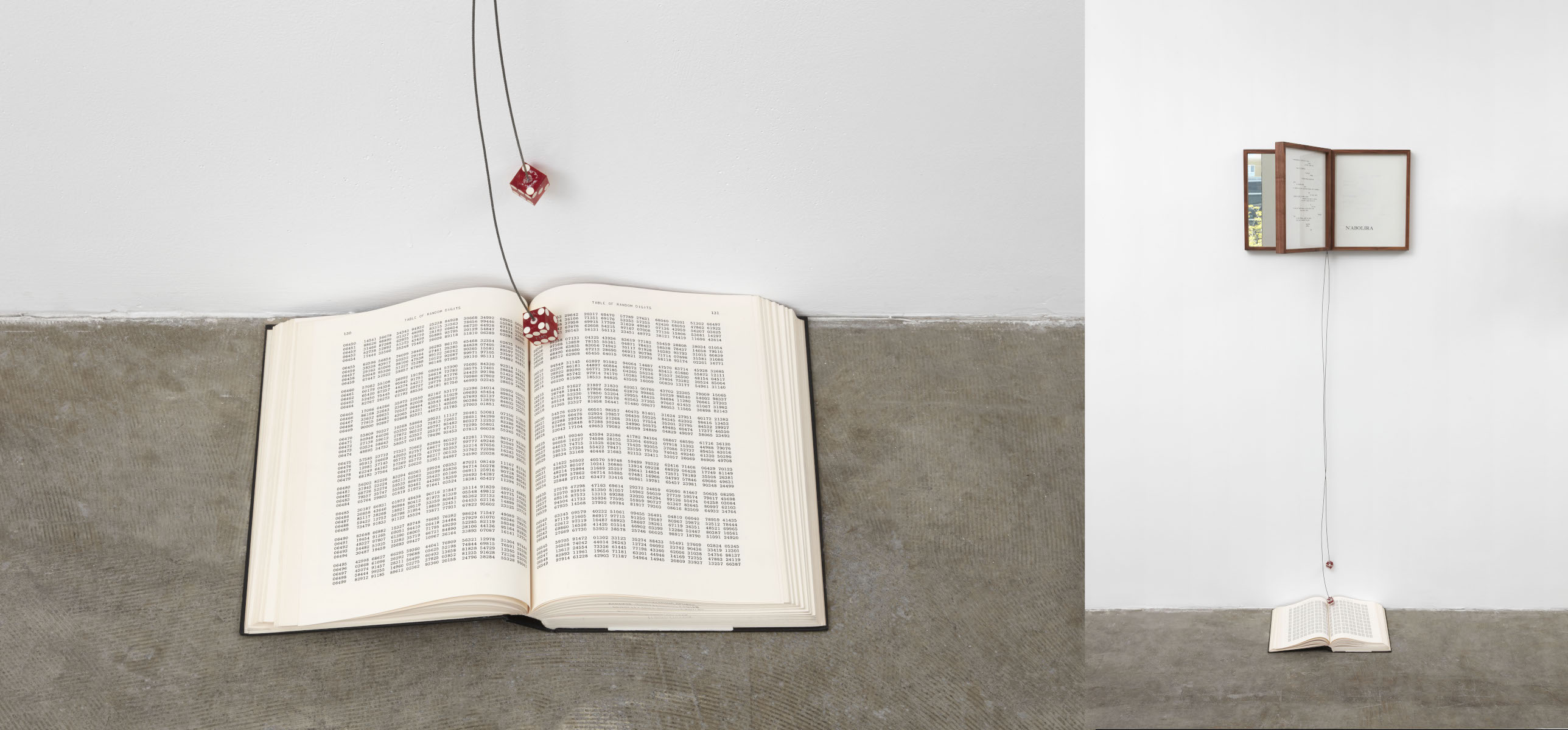

KJV: Well, we’re standing in a gallery where you’ve put together an entire show that features a roulette wheel, a vintage regulation deck from the Stardust Resort and Casino, and dice (including a pair, also from the Stardust, that dangles from Stéphane Mallarmé’s “Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard” and gently touches upon opened pages from A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates, published by the RAND Corporation in 1955). Do you feel like this show is a bit like you working out your own revenge fantasy on this Vegas culture?

Scott Benzel, N’abolira (detail and installation view), 2020. Stéphane Mallarmé’s “Un coup de dés jamais n’abolira le hasard” from Éditions Gallimard, A Million Random Digits with 100,000 Normal Deviates published by the RAND Corporation in 1955, Stardust Casino and Hotel dice, wire, wood, glass, mirror, 66 1/2 x 22 1/2 x 11 in. Courtesy the artist and Bel Ami, Los Angeles. Photos: Paul Salveson.

SB: Interesting. I don’t think of it as revenge so much as an exploration of the channels and possibilities of chance, and maybe even an homage to beating the house. I believe that’s what the surrealists were doing when they replaced the royalty of the standard deck of cards with their own hierarchy of revolutionary figures, like Paracelsus, Lautréamont, Hélène Smith… [Telepathic Gamber, 2020.]

Along those lines, my interest in the Dogecoin cryptocurrency stems from its phase transition—the transition of matter into different states, like a solid into a liquid—from a silly meme circa 2010 to an actual dodgy financial instrument circa 2020 being pumped and dumped via TikTok videos of dogs. It’s a truly ridiculous intensification of the fictions at the heart of financialization. And this is a process almost exactly opposite to Marx’s maxim that all that is solid melts into air—the solidification of a meme into something real, accomplished partly through the meme’s stickiness and the Doge’s cuteness. Even the stupidity of the whole process generates attention capital.

Scott Benzel, Mindless Pleasures, installation view, Bel Ami, Los Angeles, August 1–October 3, 2020. Courtesy the artist and Bel Ami, Los Angeles. Photo: Paul Salveson.

KJV: What do you think is the connection between capitalist risk and chance operations in the history of radical artmaking?

SB: I think that works like Hans Haacke’s Shapolsky et al. Manhattan Real Estate Holdings, A Real-Time Social System (1971) and Andrea Fraser’s essay “L’1% C’est Moi” (2011), as well as Duchamp’s “financialized” works, like the Monte Carlo Bonds (1924) and the notarization of L.H.O.O.Q. (1919), are antecedents, but I was also interested in the linkages to the Monte Carlo algorithm and the Bomb, gambling’s links to technoscience and the military-industrial complex. So, for example, the spiderweb charts in Haacke’s Shapolsky et al. reveal connections between diverse real estate entities and individuals. The connections were publicly available but obscure. In my exhibition, there’s more formal variation, but the relationships—between, say, roulette, Poincaré, Duchamp, von Neumann, Ulam, the Bomb, and Lorenz—are similarly available but obscure. They literally feed into one another. And in Fraser’s essay, she shows very clearly that increases in art prices between 1956 and 2006 correspond shockingly well to increases in income inequality over the same period. The market for symbolic goods (to use Pierre Bourdieu’s terminology) is inextricably linked to the economic, social, and political forces that lead to increased inequality. The mutability of the algorithm and its indifference to humanity squares with the mutability and indifference of power politics and bare-knuckle, winner-takes-all capitalism. Monte Carlo stands for both “La Dolce Vita” and for the algorithm that gave us Hiroshima and Chernobyl. These are the sort of occulted connections, hiding in plain sight, that I’m interested in.

KJV: So, in conclusion, there is no empathy in numbers. X

Scott Benzel was born in Scottsdale, Arizona. He was raised in Las Vegas and now lives and works in Los Angeles. He is a member of the faculty of the School of Art at the California Institute of the Arts.

Keith J. Varadi was born and raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. He has visited Las Vegas numerous times and also lives and works in Los Angeles. He is a researcher for the long-running television game show, Jeopardy!.