Christopher Rountree and Neha Choksi

Talk Fluxus at the LA Phil

The Los Angeles Philharmonic has long been admired worldwide for its relaxed and future-minded programming. Within a few years of its founding in 1919, it embraced Los Angeles’s fine weather and built the Hollywood Bowl. It gave 20th century innovators Igor Stravinsky and Arnold Schoenberg early chances to guest conduct and premiere new work. It was one of the first orchestras to give the baton to women and hire African American musicians. In 1962, a 26-year old Indian conductor, Zubin Mehta, became its youngest music director, and he straightaway infused his program with music by emerging composers (a tradition that continues in today’s Green Umbrella series). In that pioneering spirit, to mark the LA Phil’s 100th anniversary in 2019, it appointed composer, performer, and conductor Christopher Rountree as curator for a year-long Fluxus Festival. Christopher and I met for what I thought would be a short conversation on February 16 in a nondescript green room at the Walt Disney Concert Hall. As practice notes wafted in through a monitor, we unspooled our thoughts over more than three genial hours, continuing over lunch, then coffee, then chatting all the way to the door of my car parked in the Disney Hall’s underground garage. What follows has been heavily abridged.

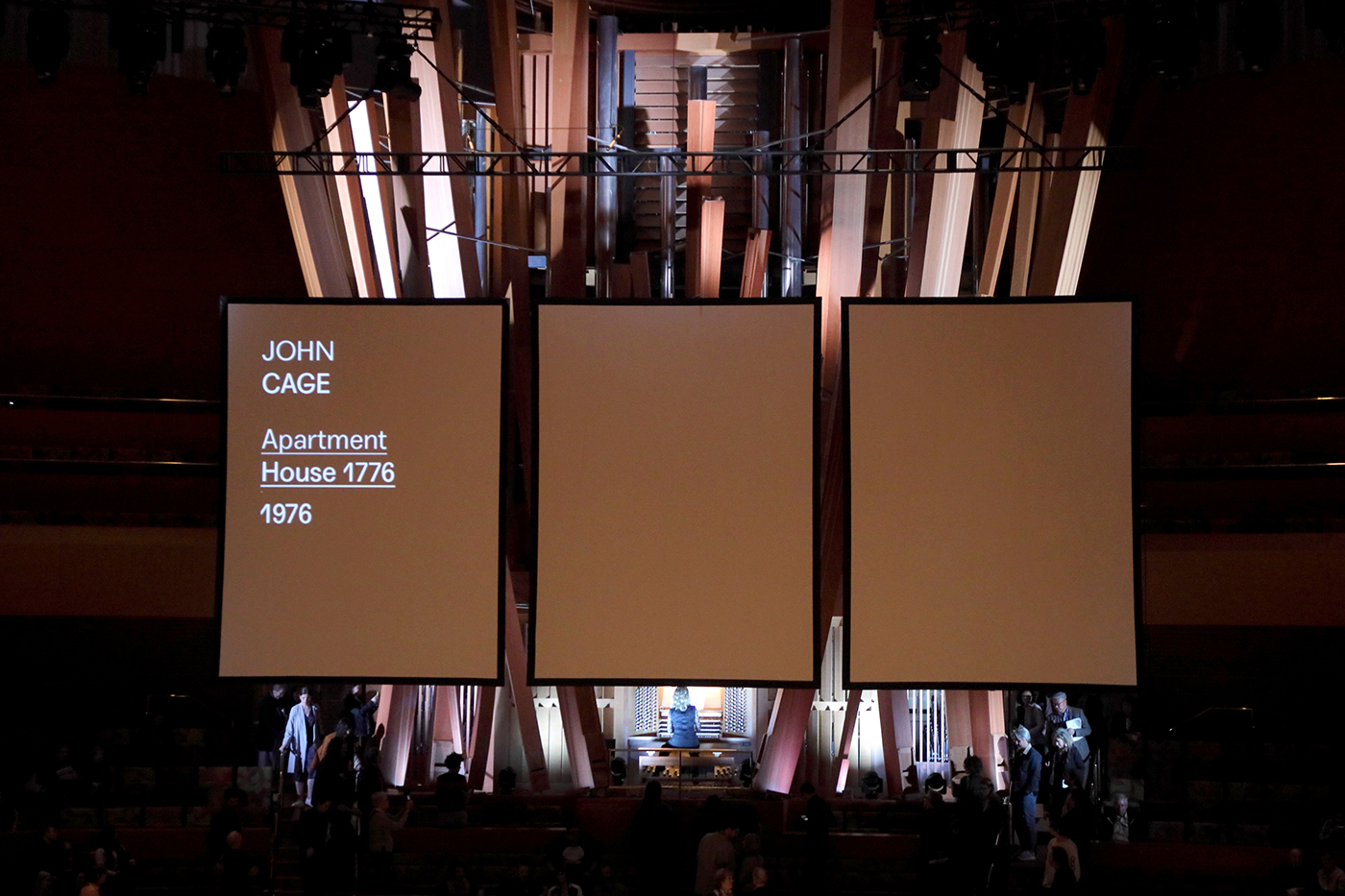

John Cage, Apartment House 1776, 1976. Performance as part of Fluxconcert at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, November 17, 2018. Conducted by Christopher Rountree, including vocalists Mia Doi Todd, Rodrigo Amarante, Dwight Trible, Odeya Nini, Andrew W.K., Joe Rainey Sr., and Georgia Anne Muldrow. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Matthew Imaging. Photo: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grud.

Christopher Rountree: How was the Ikeda/Knowles concert last night? I’m so glad you got to be a part of it.

Neha Choksi: I did not know about the new Ryoji Ikeda work. I was just expecting Ikeda’s usual tech wizardry. So, when I walked in and saw the 100 disparate cymbals in a ten-by-ten grid, it took me a moment to see the connection between that and his data mining audio-video works. Hearing 100 cymbals was like stretching a really small piece of Gerard Grisey, making one think, “Okay, now I’m going to pay attention to everything.” It makes sense Ikeda was paired with Alison Knowles’s Proposition #2: Make a Salad.

CR: And they’re both taught by rote, through an oral tradition.

NC: That makes sense—Fluxus is about scores and has its origins in music rather than visual art. I think of oral transmission in two ways. It’s either bardic, like Homeric or Vedic Brahmanical stuff. And then there’s gossip that’s also mouth to ear. May I ask what your score for the Fluxconcert would be? Text? Graphic? Vocal?

CR: The score I made is like a big list. I thought, “Here are all the dream projects that I’d like to see in a row.” And the LA Phil said, “Let’s do them all.” After that, I thought, “Well, since I’m more of a performer than a scholar, before we do embark on this, we should go talk to somebody who knows a ton about Fluxus.” And that’s when the conversation began with the Getty. They asked a lot of great, critical questions, like, “How is Ryoji Ikeda Fluxus?” Earlier I had asked Ryoji, “Do you fit?” He was like, “They’re all my heroes, so I hope so.”

NC: Ikeda is a lot easier to think of as Fluxus, but how did you come to include Berio’s Sinfonia? Was it simply because he was sampling, i.e. quoting in that work?

CR: Actually, George Maciunas programmed Berio in a Fluxus Festival in 1963. He was knighted by Maciunas’s official word. I thought quite a bit about who fits in Fluxus. In addition to presenting the “canon of Fluxus,” as it were, our next goal was to include the influences that caused Fluxus, like John Cage, even though Cage was like, “Please don’t call me the grandfather or father of Fluxus. I guess I’d accept uncle.” The last goal was to look at this moment, right now, and see who’s making work that’s kind of post-Fluxus, and who would identify themselves as participating in that ethos, and Ragnar Kjartansson and Ryoji Ikeda both said, “Yes, please.”

NC: You are parsing the ontology, the production, the dispersion. And by including a larger group of artists than those clearly Fluxus, you are knighting them, too.

CR: Many of the Fluxus artists, if you ask any one of them who is Fluxus, they all have a different answer. Actually most of the answers are, “Basically, nobody is Fluxus.” La Monte Young essentially said to me, “Well, Maciunas, he was a really good publicist.” Huge digs like that. At the same time, La Monte said, “I don’t want to be a part of this. Also, I’m flattered, and yes, absolutely, I’ll be part of it.” Kind of like, “I created that, but I’m not in it.” Though I do think Alison Knowles would say she is Fluxus.

NC: I think she does, and certainly Dick Higgins would.

CR: For sure. There was a dialogue between the people in that class with Cage at the New School. The truth is that the ideas were permeable, transferred, and shared. Just as much as he influenced Fluxus, Cage was workshopping his own ideas with all the to-be Fluxus artists around him, and incorporating their ideas into his own work (later even including Alison’s ideas in Apartment House and other pieces). But we often say, “Oh, Cage invented Fluxus.” So there’s an interesting question about which ideas came first. And the question of whose ideas are actually at the center.

Ben Patterson, Overture III, 1961. Performance as part of Fluxconcert with Los Angeles Philharmonic’s First Associate Concertmaster Nathan Cole at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, November 17, 2018. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Matthew Imaging. Photo: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grundt.

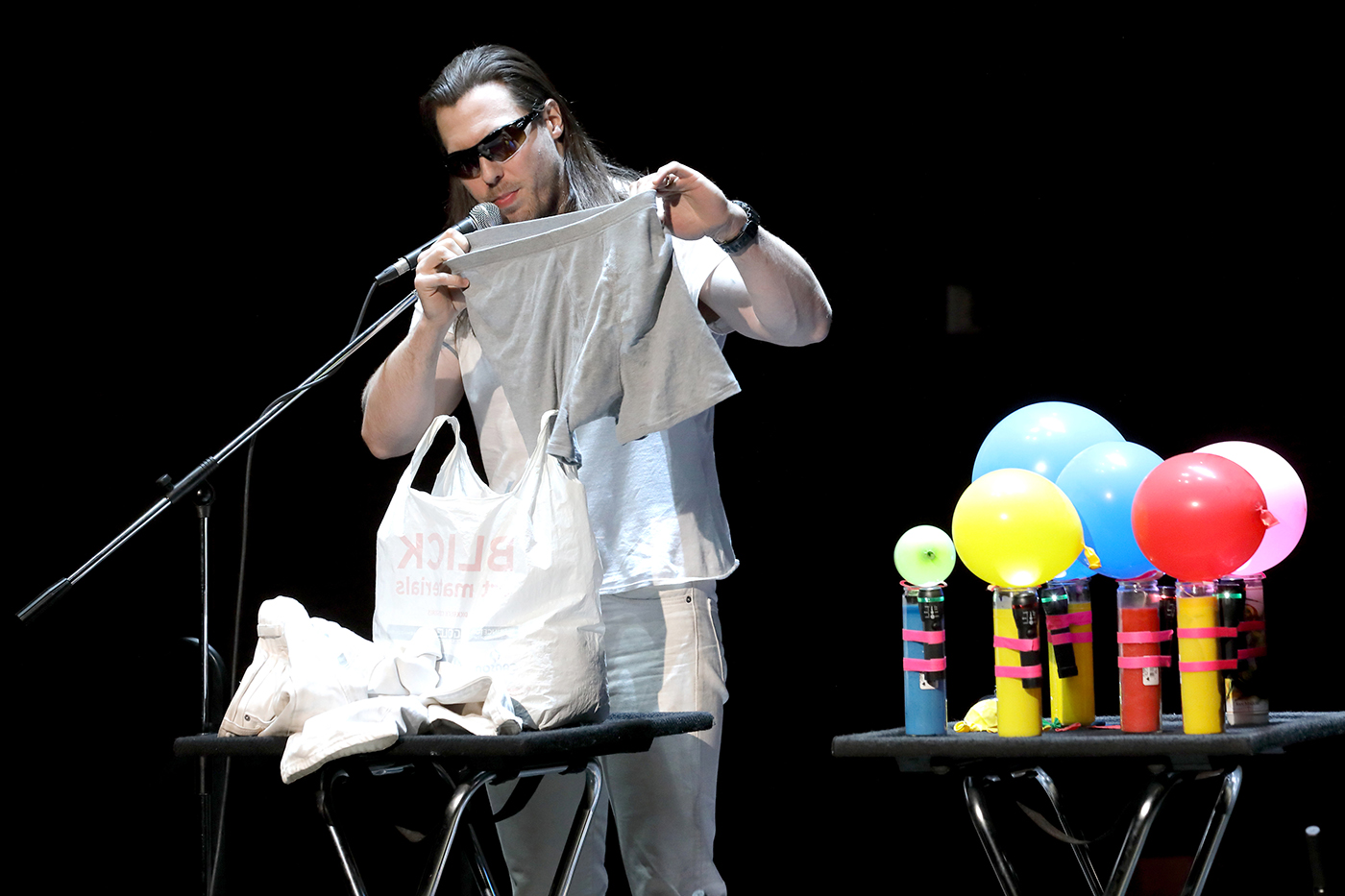

Yoko One, Laundry Piece, 1963. Performed by Andrew W. K. as part of Fluxconcert at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, November 17, 2018. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Matthew Imaging. Photo: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grundt.

For Fluxconcert, we thought about the best ways of bringing Fluxus into the space of classical music, which is deeply conservative and categorically hates self-scrutiny. Classical music has done a really good job of rarefying itself, and among its ivory heights there’s this belief that the more rarefied and valuable a thing is—the more luxury, the more Rolex it is—the better. And presenting something like Fluxus, which is starkly anti-capitalist, in a space of capitalism like the Walt Disney Concert Hall—the work and the space immediately break down. Right? And no matter how regressive or anarchic the action is, if you do it next to the words “British Petroleum Hall” and “Wells Fargo Stage,” it has so much dissonance, like seeing people make a giant salad on such a hallowed, grand stage like Disney—seeing us put down a gargantuan blue tarp, twenty of us with Alison Knowles behind five big tables, chopping amplified vegetables, mixing dressing, mixing the salad one huge bowl at a time, and then all of us watching Alison dump it, one bowl at a time, onto the tarp to be tossed in the air later, the tarp a giant mixing bowl the whole time. Then feeding it all to the entire audience over 90 minutes. That action is blissful and simple and “everyday” but under the lights of a concert hall it becomes part chaotic anarchy, part hilarious mocking of abundance. Everything changes.

NC: As opposed to seeing it on a meadow?

CR: I want to see it in a giant open field, where we all can see each other, and maybe we each make our own little salad, and it’s very personal and beautiful. We’ve all brought our own ingredients, and we all agree to do Alison’s piece, and then we drink some champagne with our salad. That’s probably the version of that piece that is the most down the center.

NC: Have you discussed your vision with Alison, about this big meadow where we’re all just sitting and chopping?

CR: No, you and I just came up with that. The LA Phil and I said to Alison, “Here is the hall we have.” This stage is actually where the piece belongs, even though the most consonant version of Make a Salad probably exists leagues away. The thing is, I wouldn’t presume to pitch my idea of what her pieces should be, ever. For me it’s like lying at the feet of the guru. My role is to accommodate her wishes as well as the LA Phil’s public facing concerns at the same time. For instance, I heard one of the catering people from Patina say backstage, “Oh no, her feet are in the salad.” And I was like, “Well, she has special booties on, the salad’s fine.” But to do this in a major public setting, it shows all the seams, right? Alison said, “We want people to come up to the stage,” and the Fire Marshall was like, “Absolutely not. It’s a fire hazard.” Then the only other option is the most corporate option, which is to Scotchgard all of the seats in the hall. So we Scotchgarded 1,200 seats for the show.

What I’ve noticed about bringing Fluxus to a space like Walt Disney Concert Hall, and into an organization like the LA Phil, is that it keeps changing that organization. And smashing it into its own walls over and over and over and over.

NC: To advance a canon is also dissonant.

CR: Correct. I wanted to use Fluxus as a slingshot. In new music we’re already moving toward performance and levity and mindfulness through everyday stuff, toward the Cagean idea of music being all around us. And classical music is moving rapidly toward theater. Fluxus is a really good way to talk about that motion. The way to do it, though, is to hook in Cage and Berio and someone like Steve Takasugi into our “canon of Fluxus” just like they’re part of the “canon of classical music.”

Concertgoers with Kool Aid by mixologist Arley Marks as part of Fluxconcert at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, November 17, 2018. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Matthew Imaging. Photo: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grundt.

NC: So what did all of these disparate people think Fluxus is? As an artist, I’m trained to think about Fluxus as part of my canon, but how does a composer like Steve agree to being seen as Fluxus?

CR: I can speak for myself, as a performer. Classical music is all about rules, it’s about perfection. And then I met Fluxus, where one is endeavoring an action, a path, but the outcome is unimportant. Your assignment is to simply do the work. Fluxus pulled the sheet off of process for me. Where classical music is all about shielding, Fluxus causes an immense level of vulnerability.

NC: You have now mentioned classical music as “hating scrutiny” and “shielding.”

CR: It’s really intense. It’s incredible the number of times I’ve heard something like, “Well, we were on tour with the orchestra, and two of the bass players got in a fist fight because one of them took up too much room on the stage.” That sounds like a rock band. It’s about how much space one has to be an artist in the giant mass of artists that makes up an orchestra.

NC: Does humility play any role in classical music, and what role does humility play in Fluxus?

CR: Humility in classical music is in the teacher-student relationship, for sure. We venerate the highest achievers; it’s kind of like venerating celebrity. My favorite Fluxus works cause mindfulness, which is related to humility, but these works are very often brash. The performance of Make a Salad is a brash action, and when I go make dinner, I hope that I make dinner differently, more mindfully, because I’ve contemplated Alison’s work.

NC: Is it so one-to-one? Some academics like Natilee Harren relate Fluxus to social practice. The difference is that social practice is invested in interdependence and community and effecting change. And Fluxus is not. That’s where this question about humility comes from. The brashness of Fluxus may result in something that is community-oriented, like giving away salad, but the action is toward mindfulness. I’m looking at the salad and I’m feeling hungry. Or I’m seeing 100 watermelons splatter. It’s a visceral thing for me as an individual human being. I’m not thinking about my community. I’m thinking about my body, my living, my joys, and my affect. The person sitting next to me who’s also having the same reaction to the salad—we’re both feeling hungry, but that’s about it.

CR: Everybody that’s been really pissed at us has been applying Fluxus to a community. There’s this personal guilt. And as audience members we sometimes send the guilt out. “Wait, we’re going to destroy another watermelon? We’re going to do that again in three minutes? This is a terrible idea. There are people that need food. This is real.” That feeling is why these pieces exist. During the rehearsal of a violin being dashed onto the stage by our Associate Concertmaster Nathan Cole, he said, “I’m really conflicted about this. I’m excited to do it. We have to get a violin good enough for me to play this beautiful piece of Biber, this ancient baroque piece, but it also has to be bad enough for me to be able to destroy it.” We found the right instrument, and he said, “I know what I’m going to think about when I carry it across the stage. My family had a sheep farm, and we realized early, as kids, we couldn’t get too attached to the sheep. I’m going to think about that with this violin. I’m going to play its last song, and then I will sacrifice it.”

To see Nathan grapple with Nam Jun Paik’s One for Violin Solo (1962), and witness his orchestra colleagues’ frustration that he was going to destroy an instrument that they could have given away to a student or someone else that needed it. Those musicians all watched the performance, they freaked out backstage watching the monitor, many of them freaked out watching it in the house. And then they all came onstage for the rest of the concert program, and I watched them all filled full to the brim with joy. When “Fluxus happens” to a classical music person, I see it change them, and it was beautiful to see the change in them.

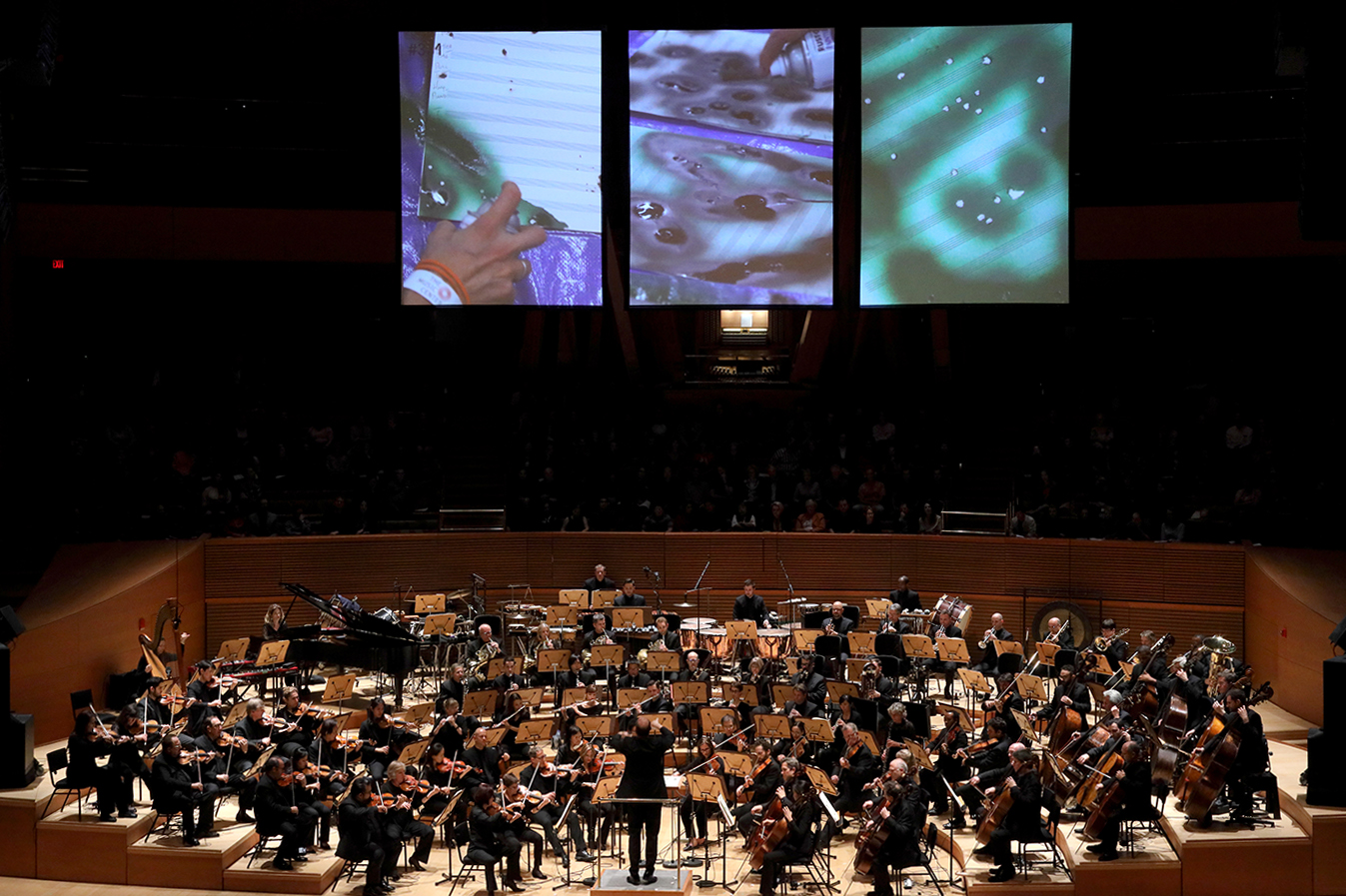

John Cage, Apartment House 1776, 1976. Performance as part of Fluxconcert at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, November 17, 2018. Conducted by Christopher Rountree, including vocalists Mia Doi Todd, Rodrigo Amarante, Dwight Trible, Odeya Nini, Andrew W. K., Joe Rainey Sr., and Georgia Anne Muldrow. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Matthew Imaging. Photo: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grud.

NC: One could say you made this Fluxconcert so that your friends could be transformed. Conversely, a lot of the artists who came to Fluxconcert had mixed reactions, right? Because they’re so heavily invested in Fluxus as part of the visual art canon, some complained about how they thought you were massively deviating from their understanding of Fluxus’ gravity of presentation. So, even though the classical musical world and the visual arts world reacted from different points of view, it’s essentially the same reaction of being uncomfortable with what is outside their expectations.

CR: I’m really endeavoring to pull both these two disciplines toward one another. These Venn diagrams do overlap! And what I’m trying to find is that place that makes the hand-hold, the joining, happen the right way. I’m trying to address this question about Fluxus: “Whose work is this?”

NC: When Travis Diehl asked me to interview you, he added something like, “And make sure you ask about Andrew W.K.” Which I understood to mean, “Why was he included?” And I wrote back something along the lines of, “Maybe Chris thinks Fluxus is a party?” So, do you? The party feeling is what I think some visual artists objected to. Referencing the concert at Wiesbaden, an academic said to me, “Fluxus is sequential, it’s measured, it’s proper, and this L.A. Phil thing is a free-for-all, I can’t handle it.”

CR: Andrew performed Yoko Ono’s Laundry Piece and Cage’s Apartment House 1776. I think in both pieces Andrew followed the rules, actually. The rules in Cage’s piece are simple. In that piece, the way I saw it, Cage basically is saying, “Sing your own spiritual truth.” Full stop. That’s the piece. It’s more complex than that, more historical than that, and that’s me interpreting Cage a little bit. But Cage is really problematic in a bunch of ways, and in interpreting him, we’re able to avoid some of the—

NC: Identity politics stuff, like what it means to specify that a Sephardic person is going to sing something from their tradition.

CR: Correct. So my prompt was, here’s the piece, here’s a recording of the piece, and I simplified Cage’s prompt to just say, “What’s your spiritual truth and can you sing that?” And Andrew said, “My spiritual truth is my seminal rock hit of 2001, ‘Party Hard.’” And I was like, “Oh, whoa.” The Cage piece, for me, if it’s right, is everybody given space to communicate what they feel their lineage is. Essentially Andrew is saying, “My lineage is communicated best through a thing that I made.” And as curator and conductor, I was trying to put myself in that place of, “Oh, if somebody else, from a different discipline, made the choice to include their own music in Apartment House, and I had a negative reaction to their including their own work in this way, but let’s say that they weren’t a white dude, notably if they were not as pale or as male as me, would I ever edit them?” And the answer is, “Absolutely not.” And so I thought, “Maybe we’ll just set a simple parameter up, and ask everybody to respond to the same parameter.”

Los Angeles Philharmonic conductor Christopher Rountree and guest artists on stage as part of Fluxconcert at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, November 17, 2018. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Matthew Imaging. Photo: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grud.

NC: Depending on how far apart or how close the performers are, you can have an identity war going on with people singing their truths to each other.

CR: It was really painful for me. I was watching and thinking, “Oh, they’re all competing.” And then both Dwight Trible and Odeya Nini said to me, “We don’t want to compete. What if we work together? Is there a way we could work together?” And I was like, “Yeah, I think you should try to solve this with the performance. At the same time I think the audience is going to talk, so I think it’s going to be incredibly loud. And it’s probably going to be difficult to solve.”

NC: Why did you program Apartment House 1776 in the interval?

CR: I had conceived of the piece functioning as a convener of energies, something spanning the first half of the program, through the interval, to the second half. And spiritually it could work as a connector. It also seemed like an appropriate place for a work that is supposed to sound like a dinner party. In hindsight, though, I might change it. For me it was devastating.

NC: That’s really gratifying to hear that you might change it. That you are still thinking about it. There was all the competition between the singers, but there were also friends and acquaintances milling around me. I wanted to see the work but couldn’t attend to both, and the amount of anxiety it provoked in me, not seeing the Cage properly…

CR: It’s possibly what Cage wanted, because what Cage said about Apartment House was, and I’m going to paraphrase him, “Maybe when America works better than my piece, it will be a good place to live.”

NC: Stunningly apropos.

CR: It’s like we’re supposed to be honoring everyone’s lineage and spiritual history, and we’re supposed to all be here together and it’s supposed to work, but it doesn’t work. It’s like how democracy and capitalism don’t work together.

NC: And then to include somebody like Andrew, just his presence. Here is a person who’s shrouded his own origins in so much mystery, and to have him represent one fraught American origin story is interesting, because it’s like this obliterated past that is reinvented, almost like Joseph Smith‘s story, you know. Myth-making, cult-making, suppressing some things and enhancing others—to have a party, to promote partying, which is its own cult.

CR: I think Fluxus is a polemic object. I witnessed a conversation between two of the salad choppers right before the Knowles concert, and they asked Joshua Selman (Alison’s long-time collaborator), “What’s the meaning behind the work?” And Josh was like, “For Alison, it’s anarchy.” That’s such a bold, amazing answer. But, for me, that’s not what Josh’s performance meant. Alison’s piece to me is about joy and discovering beauty in the everyday. Him dressing up of people with lettuce cravats adds topics like waste and posturing to the piece, which I guess are there to begin with when you dump a bunch of vegetables onto a tarp on the floor.

Alison Knowles’s Wounded Furniture performed by Elise McMahon, part of the LA Phil’s Fluxconcert at Walt Disney Concert Hall on November 17, 2018. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Photo: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grudt / Mathew Imaging.

NC: We started our conversation talking about the choreographed nature of Ikeda and the parallels to the Knowles. I had an acute observation, something that I noticed and that bothered me. The Ikeda featured ten men, and all of them were of a certain age, build, look, girth, and even more astonishing was that nine of them appeared to be white. It was in stark contrast to the range of bodies, ages, genders, and races in the Knowles. Did Ikeda not have an opinion on that? You? The LA Phil? It was just this morning that I read Joshua Barone’s writeup of Yuja Wang’s new concert in the New York Times, and he takes her and her collaborators down for the opposite, for a complicated attempt at satire that plays into the stereotypes and makes for decidedly unfunny, even offensive racism. Hell, he even solicited Jennifer Koh to speak, in a way, against Wang’s work. One of his paragraphs starts with him wondering about the Asian-American children in the audience and how they felt about it. I, too, thought about that when seeing the piece today. What does it mean for a Japanese Parisian to be putting on a show with white men? What do the other women or Asians in the audience feel? I remember thinking when reading the Barone that seeing Asian women rule the stage sadly seems like a victory today, and that I am happy the kids got to see that, even if I might have found it offensive. So what are your thoughts on this?

CR: Well, surprisingly, Ikeda didn’t have a problem with or plan about the composition of the players in terms of race or age or anything else. Of course, I did notice it during the rehearsal process and found it a bit hair-raising. I wonder now if I should have strong-armed the LA Phil hiring process or talked to Ikeda. The problem is how contract hiring works in our field. Usually you get one person, in this case a contracted percussionist, to find the rest, then a list is generated, and the LA Phil can only go in the order of the list. The contractor calls people down the list, some say yes, some say no, you can’t pick and choose. It’s a real problem, one that propagates itself, and one that’s tricky to address because new music has been for so long a predominantly white and predominantly male space. It’s something we’ve got to work on at every level, from representation in educational spaces, to hiring practices at major institutions. And at the end we’ve got to face the fact that systems built in the late 20th century to protect workers in the arts, because of implicit bias, they don’t protect everyone equally. And we’ve got to change that.

NC: You’re obviously invested in getting various people together. You’ve done that time and again, whether with wild Up, or Noon to Midnight. Do you feel like you’ve contributed to community?

CR: God, I hope so. Years ago, there was this five-bedroom house in Highland Park in Los Angeles, up on one of the hills, and my friend who is an audio engineer and his partner said, “Hey, we need a bunch of people to move here.” So that was my first place when I moved back from grad school. That became the home for wild Up for five years. That first year we had dinner parties every three days at the house. It became the hub for new music in our community. It’s not like we were doing shows there, but music brought us together and fueled us. It was an era. It was incredible, and actually I feel like my big goal is to use music to show people how they can be near each other, and near each other better.

NC: And in new and different ways each time.

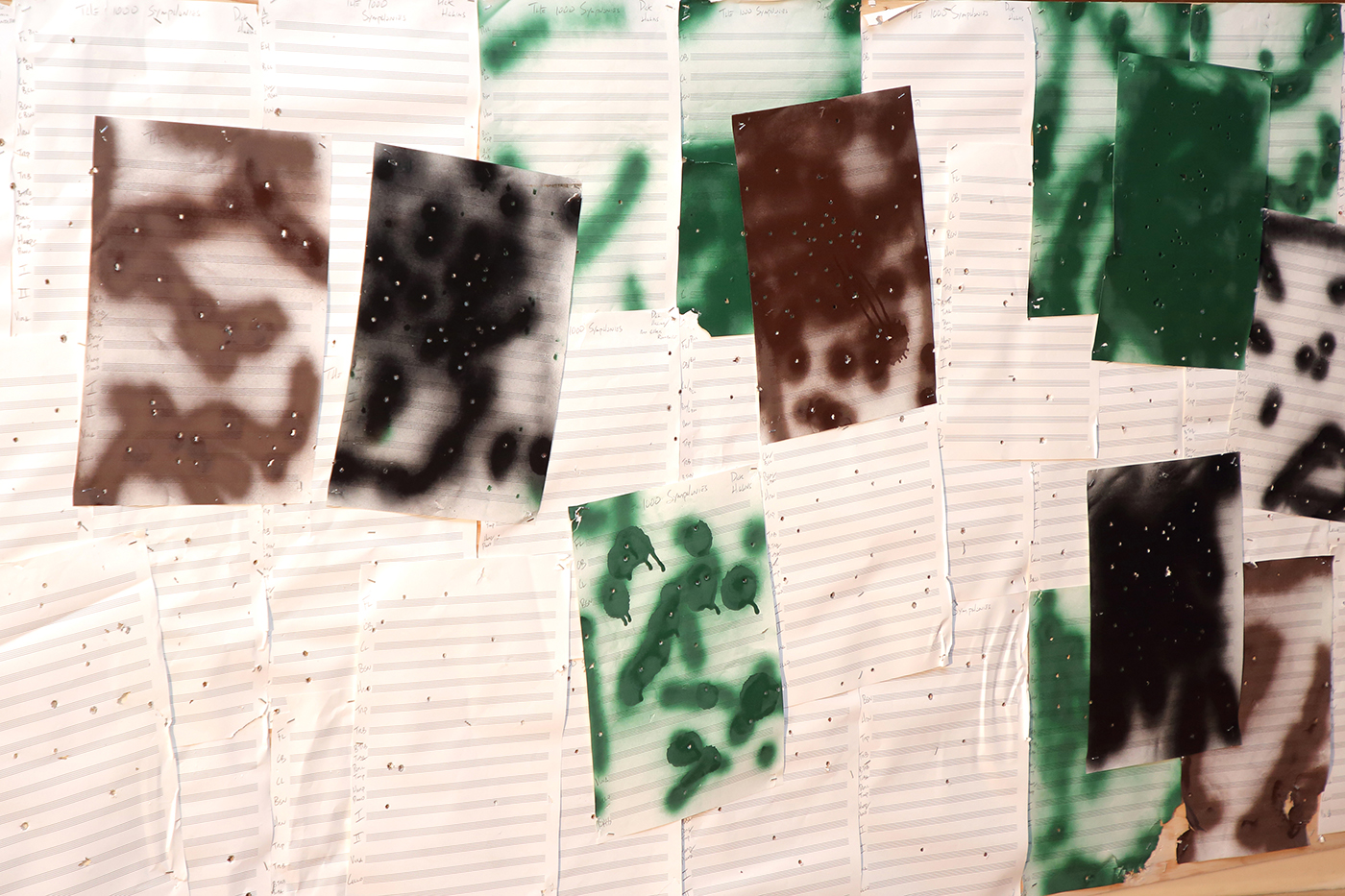

Score for Dick Higgins, The Thousand Symphonies, 1968. Performed as part of Fluxconcert at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, November 17, 2018. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Matthew Imaging. Photos: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grundt.

Dick Higgins, The Thousand Symphonies, 1968. Performed as part of Fluxconcert at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, November 17, 2018. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Matthew Imaging. Photos: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grundt.

CR: The thing about music is that it opens you up in ways that you’re unaware of. You listen to a piece of music, let’s say with one other person. Suddenly you’re both open and you communicate and you’re bonded in a deeper way.

NC: The art world and the music world don’t seem to meet or bond as often as they should.

CR: Like, ever.

NC: Really? Okay, possibly.

CR: I don’t know if I can name one person who is squarely in both worlds. But I think this festival is trying to do that. I get asked often, “Who’s writing for orchestra, who should we commission?” Or, “Who are your top choices?” And very often at the top of that list I have either a conceptual artist or a visual artist or a sound artist, somebody outside of classical music. Or even a film composer, like, “You should commission Mica Levi.” And they’re like, “Who’s that?” And I’m like, “She’s real famous. She’s way more famous than everybody on your list. Also, listen to this score from Under The Skin, it’s the greatest thing that’s ever happened.” It’s clear to me that so many artists, they’ve been classified as “not our thing” by classical music writ large. Classical music has a lot of Western, hegemonic power problems, so even subtly giving that power away to other disciplines is a critical step.

NC: Why do this? What’s coming back in? What’s feeding you?

CR: I’ve been thinking a lot about that recently, specifically with this work. “What good is it to make art?” And I’ve been feeling really shitty about it. The only answer that I’ve gotten that makes me feel like it’s the right answer is: to draw us all closer together. My dad passed away when I was 20, and when he died I thought, “What does my ideal life look like?” I had this vision that I kept coming back to, which was a bunch of people around a big wooden table. And of course I didn’t know who Alison Knowles was at that time. I just envisioned us passing these huge bowls around, laughing, and I could see the kitchen, and I knew we were talking about art making, and I knew that it was not just music. There were dancers there, there was a playwright there. It was utopian, all these people gathered in this place, talking about their ideas, and not necessarily even doing them.

When you ask, “What does the score of Fluxus look like?” I think that the score of Fluxus is all the conversations that happened after the thing. This idea of a score creates situations where people say, “Why is this person doing that?” “That pisses me off.” That’s the score. “I can’t believe it, when the cymbals were happening I was having an auditory hallucination, I heard a choir singing, and I heard five pitches, how is it possible!” That’s the score.

Ken Friedman, Sonata for Melons and Gravity, 1966. Performed as part of Fluxconcert at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, November 17, 2018. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Matthew Imaging. Photo: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grundt.

NC: That gets me thinking about sequence versus simultaneity, the ideas of time that Einstein and Bergson disagreed about. You talked about trying to put many things together at once for the Fluxconcert, and a part of it feels anarchic, but on the other hand, Nathan Cole’s solo set of four pieces (Patterson, Young, Paik, Ono) was very sequential, programmed. Even if everything else was programmed, too, the affect of that was different from the affect of running around to catch the Cage.

CR: In the Cage, the singers perform on a matrix, but what they’re doing within their box is quite open. There are all these different instrumental quartets happening at different timings, and hymns are happening all over the space. Each event is unconnected but also aleatorically interrelated to the all of the others. Apartment House 1776 is kind of like experiencing all these things in space, with absolute non-linearity. So we wanted to do the opposite with the four pieces that Nathan Cole performed solo: Patterson’s Overture II, Young’s Compositions 1960 #13 (containing within it H.I.F. Biber’s Passacaglia), Paik’s One for Solo Violin, and Ono’s Piece for Orchestra to Yoko Ono. Classical music is so rigorous, in terms of order and etiquette and all of that. Somehow when you find a laugh track and then a violin in a box, play some of the most beautiful music ever (as well as you can), then dash the violin to the ground, smash your head into the wall and then bow—that clearly demonstrates how Fluxus and the etiquette, the linearity of classical music are going to play with and also against one another.

NC: That etiquette is what you point to with when you had the sort of cheesy, self-referential texts above the stage saying, “Don’t Clap Now.” What’s going on there?

CR: If you do Fluxus in a pure way, it doesn’t have a director. But we had a director.

NC: Ah, you had to admit it. I’m also interested in the meta-narration of the work where the singer ends by saying, “Thank you, Mr. Rountree.”

CR: Berio has these remarkable moments in Sinfonia where one of the singers starts asking questions of the audience, then narrating the concert. He introduces the band one by one, as members of the vocal octet ask questions of each other, and of art itself, and when one of them posits an answer about, “Why this work, why here, why now, what’s the value in this all?” another singer screams, “Say it again louder!” What could be more Fluxus than that! Anyway, not only does that tenor introduce the whole band and call to the critics in the house to laud another piece on the program in tomorrow’s paper (we used Cage), but he also thanks the conductor by name at the end of the Scherzo.

R. B. Schlather, Karaoke, 2018. Performed by Richard Kennedy as part of Fluxconcert at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, November 17, 2018. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Matthew Imaging. Photo: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grundt.

About having a director: I’ve been fascinated, obsessed even, with R. B. Schlather for a few years. He’s the kind of guy who’s like, “We’re doing Macbeth, but the set is forty grey wooden camp tables and six hundred rotting pumpkins.” He’s a performance artist, a performer in the everyday sense, a thinker, and a director. We were really lucky to have his directorial eye on every part of the Fluxconcert in November, from the dozens of pieces performed in BP Hall, to the Ken Friedman Sonata for Melons and Gravity outside, to the pieces in the garden, to the box and the laugh track for Patterson. Having a dramaturgical eye and mind on a show like that one, particularly for an audience in a typically classical space, was critical to the show succeeding.

In terms of that quartet of pieces that opened the show, R. B. and I talked about if we should write a piece that says, “Do four Fluxus pieces sequentially in order to change the narrative.” And we almost put that new piece on the program. One of the things I love most about this work is—who’s the audience, who’s the author, what does the word “composer” mean, what does the word “performer” mean.

Nam June Paik, One for Violin Solo, 1962. Performed by Los Angeles Philharmonic Concertmaster Nathan Cole as part of Fluxconcert at Walt Disney Concert Hall, Los Angeles, November 17, 2018. Courtesy of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. Matthew Imaging. Photos: Craig T. Mathew & Greg Grundt.

NC: Those concerns get addressed in your piece, Commitment Booth / Commitment Anthology (for Hope) (2018). I wanted to talk a little bit about it because I wanted to scream in the booth, but I felt pressured by the form you handed out that solicited a written verbal response and the injunction to read it out. I regret not screaming. I regret abiding by the form’s address, and adhering to all these social rules, the pressure to get to my seat, to not embarrass my friends, et cetera. Can you tell me a little bit about how you see this as belonging to the Fluxus tradition? And what are you going to do with all the video and forms you have collected?

CR: As of now, I have no idea what I am going to do with the collected material. I was interested in setting up a situation before the concert starts, one that primes the mind for what a listener or audience member is about to encounter. It was a moment for me to listen to their ideas and shepherd a bit of their questioning. A situation where each participant has a chance to commit to or to renew their commitment to hearing music in everything everywhere in the world. Or to not. x

In 2010, Christopher Rountree created the renegade 24-piece ensemble Wild Up, now an institution in its own right. He has since collaborated with the likes of Björk, John Adams, David Lang, Scott Walker, La Monte Young, Mica Levi, Alison Knowles, Yuval Sharon, Sigourney Weaver, Ragnar Kjartansson, Ashley Fure, Missy Mazzoli, Ryoji Ikeda, Ted Hearne, and many of the planet’s greatest orchestras and ensembles including the Chicago Symphony, San Francisco Symphony, Los Angeles Philharmonic, Opera national de Paris, LA Opera, International Contemporary Ensemble, Martha Graham Dance Company, and Washington National Opera. Rountree is a seventh-generation California native descended from Santa Cruz County sheriffs. He lives in the Silver Lake neighborhood of Los Angeles.

Neha Choksi is an artist who lives and works in Los Angeles and Bombay. Choksi is a member of X-TRA‘s Editorial Board.