In a sublevel computer lab at the University of California, Irvine, some twenty monitors display the same feed, roughly synched. Tinny sound plays from the internal speakers of gray Mac Pro towers. This is Modules by Lutz Bacher, part of B L U E W A V E L u t z B a c h e r, organized at University Art Gallery at UC Irvine by artist Monica Majoli. A close friend of Bacher’s for decades, Majoli worked closely with the artist to tailor four pieces (three of which are making their debut) to five different spaces on campus. Bacher died suddenly in May of 2019, age 75. Seated at a desk, watching Modules play, Majoli speaks with X-TRA’s Travis Diehl about her experience shepherding what turned out to be Bacher’s last new works.

Lutz Bacher, Modules, 2019, installation view, Contemporary Arts Center, UCI. Photo: Travis Diehl.

MONICA MAJOLI: When Lutz turned 75, an image of her collage, The Lee Harvey Oswald Interview (1976), was on banners all over New York, advertising Everything is Connected at the Met. It was such a lovely moment. What made her career at the end? I guess everyone caught up with her. She’s one of the statistics of older women with entire decades’ worth of work, entire lifetimes overlooked—and finally they’re recognized after having proven themselves over and over and over again. She’d been making this work since the 70s.

… photos of New York City lampposts, decked with banners advertising an exhibition at the Met; Bacher’s collage of Lee Harvey Oswald…

Part of it too, though, is that the art world became so much about wealth and the market and what things are worth. Lutz really played with that idea. Sometimes leaving the price tags on the objects she used in her work. She loved the fact that The Lee Harvey Oswald Interview was a Xerox. I remember when she told me that she sold it to the Met in 1999. She was laughing and said, you would not believe how much money they spent on a Xerox.

TRAVIS DIEHL: It’s really great to sit here with Modules (2019)—seeing all these images of her installations on the monitors—while we’re talking. It reminds me of her brown cardboard book, with images of all of her work…

MM: Oh, Snow (2014). Yeah. That’s a beautiful thing.

TD: It’s a kind of catalog raisonné, but with no explanations.

MM: Well, there are explanations. She wrote them herself, they’re very pithy and they’re very much her way of talking. Some of them describe what will happen to each piece when it’s hung—to be suspended in a corner, for example. The images show us raw materials, but she expects us to understand it as art.

TD: Did Lutz teach?

MM: She taught for a very short period of time, I would say a couple of years, at UCLA shortly after I graduated in 1992 with my MFA. Our mutual friend, Liz Kotz, who wrote some really important early pieces on Lutz, brought her to my studio around that time. That’s how we met.

TD: You said she had students in mind when she chose Modules for this show, which is set up in two locations: on every monitor in this computer lab, and a single monitor in a back room near the freight elevator. There’s a behind-the-scenes feeling to the video, and also to its placement.

MM: Modules is a two-hour long compilation of videos and photos exploring spaces that she was exhibiting in. Oftentimes, it’s footage of the space before she installs. She was thinking about the students here who would watch it. She was very specific about wanting it to be on monitors. She was very interested in the idea of the individual student, a single person forced to sit in a chair.

Lutz Bacher, Rocket, 2018, installation view, Contemporary Arts Center Lobby, UCI. Photo: Jeff McLane.

TD: There are four works in the show, and they’re in five different spaces: two separate art galleries, this computer lab, the computer in the storage room, and the lobby. How did you think about distributing the show across the university?

MM: Lutz just loved space. When you told her that there was an empty space, she would think about how to fill it. I was visiting her studio, telling her about these beautiful new galleries at UCI, and she was like, well, what if you showed this piece? She pointed at Moskva. And I said, are you serious? This is a major work. And she said, well, I could just roll it up and mail it to you.

TD: It’s interesting how Blue Wave (2019) is installed—it’s just a video of a huge blue tarp, projected twice, into two of four corners, barely covering any wall space, but it also takes up the entire gallery.

MM: I know, it’s dramatic, isn’t it? The presence of the work. And the way she uses sound.

TD: The equipment too—the projectors are very present.

MM: She was a master of the spare gesture.

… an irregular polygonal billboard shows the sections of a Saturn V rocket, disassembled, displayed in a field; scattered visitors stare up at the pieces; the billboard’s shape echoes that of the building it hangs on…

This is Rocket (2016–2018) installed on the exterior wall of the SITE Santa Fe. She was working with the angles of the architecture. She would sometimes refer to what she did as interior decorating. She had a moniker that she used, an alias, Dusty Baker, and that was her terminology for that—you know, I’m doing the Dusty Baker. The idea being that she’s making aesthetic choices based on the aesthetics that are already there.

TD: I’m curious what it was like—as an artist yourself, but also as a friend of the artist—to install the show without her, without Lutz.

MM: You know, it was very painful. I miss her. I miss my friend. It was a beautiful experience because I felt very close to Lutz. I always imagined this whole different kind of experience, obviously—being together with Lutz, all the fun we would have. But I was never sure if Lutz was going to materialize here. She talked about doing a site visit at one point in April, literally a month before she passed away. And that didn’t happen.

I’m not somebody who works with other artists’ work. That’s the other thing. I’m not a curator. And this was a huge undertaking. It was very emotional for me to have Lutz’s work placed in my hands. That was scary, to be honest. Because I was coming up against desperately wanting to talk to my friend, and not being able to.

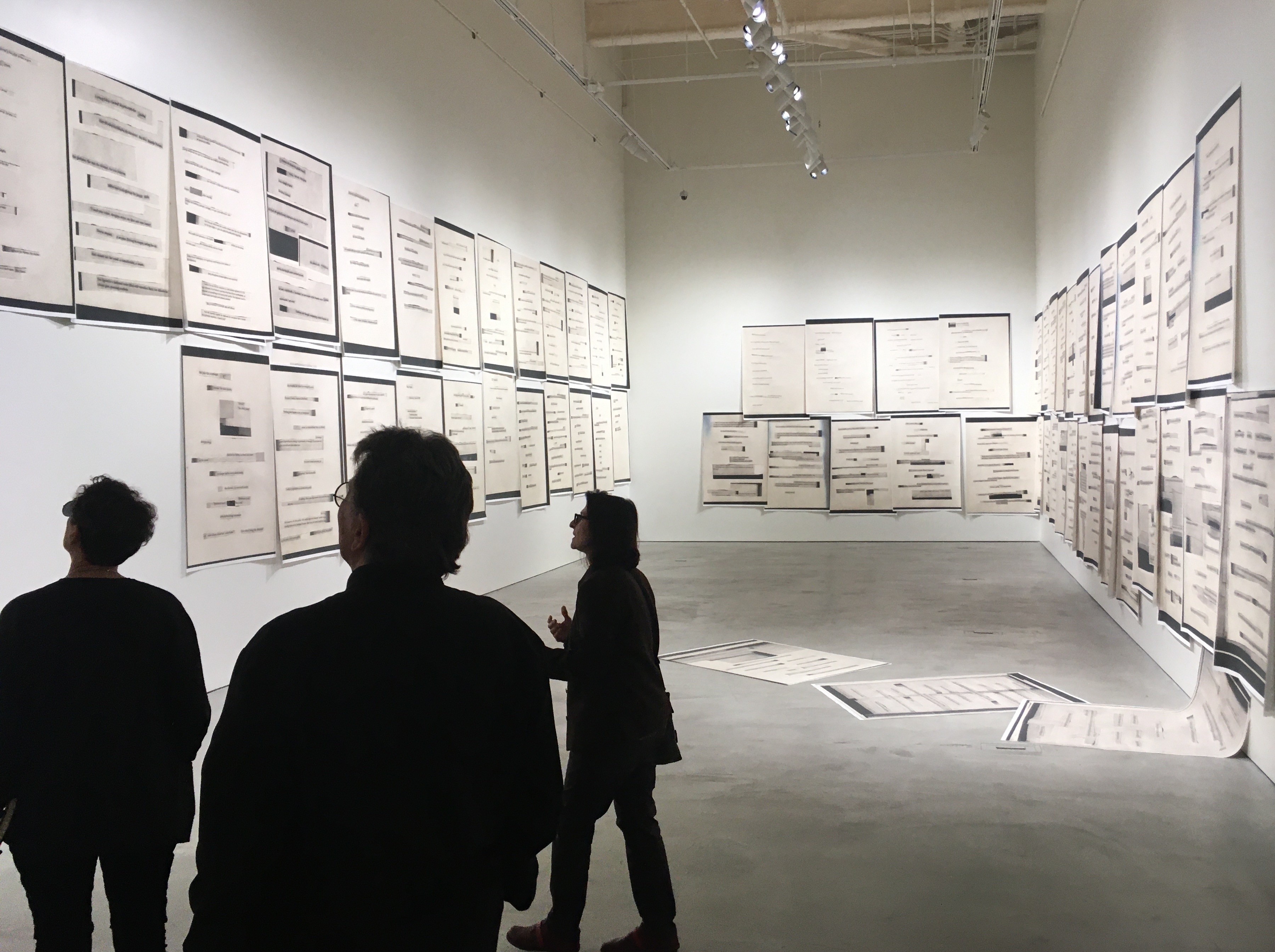

Lutz Bacher, Moskva, 2019, installation view, Contemporary Arts Center Gallery, UCI. Photo: Travis Diehl.

For example, Moskva (2019) is a massive piece and it had never been installed. For that, I had the help of Cole Root, the exhibition designer at Greene Naftali, Lutz’s New York gallery. We knew that Lutz had wanted it hung with nails or pins. We knew that she had ideas about falling pages. So that was another process, to figure out how to get the book to fall to the ground and have it feel natural. I felt we shouldn’t be so precious with the piece, we needed to take chances. But I also had this idea early on to use the pages in the images as the level line. I wanted that underlying structure to be there and to be felt, even if it wasn’t apparent. I needed something to be stable.

TD: As we were walking through the show earlier, you were talking about Rocket, the vinyl print, and how, rather than hanging it flat on the wall in the lobby, you kicked it out with a wedge—and how at that point it felt like Lutz. What does that mean? What is that feeling?

MM: I think in a certain way, she worked with very definitive gestures. But there’s a great deal of beauty and subtlety and nuance to her work, as bold as it is.

… a gallery worker rolling vertical stripes of a deep gray on pale gray walls; patchy, almost in waves of density; the video cuts forward, work in frames has been installed on the wall, and the paint remains in that first, ‘unfinished’ state, an all-over uneven gray…

For instance, she was installing this show in New York called The Long March. She had already designated all these different grays, all the different paint that she was going to use. She watered down the paint for the bottom coats, and only one coat of the darkest gray was on top in the end. Like, how beautiful is that? Right? It was these simple things that, in her hands, she made so rich and sensual and unexpected. I think the gesture with Lutz was the surprise. So much of it had to do with her invention and her belief. There’s a kind of drama in the simple, unexpected gesture. Look at how gorgeous those walls are.

There’s precision and exactitude, but she was very much a process-based artist. She would work with the material, like the projection of the blue tarp, Blue Wave, it started as, oh, let’s use both sides of that freestanding wall and have six matching projectors. I was trying to round up six matching projectors. Then, she realized—actually the last day she and I spoke—she decided, no, actually the best installation of this work is the corners. It was so magical. As it turns out, we only needed two projectors. Projecting into the corner is such a simple gesture, but it creates this supernatural effect, where the image really becomes flat. If you stand at a certain point in the space, it feels like you’re looking at two flat screens, and then when the shot starts to move, you can see that the architecture underneath coming through.

Lutz Bacher, Blue Wave, 2018, installation view, University Art Gallery, UCI. Photo: Travis Diehl.

TD: I think of Blue Wave as a political piece. In some sense very emotional and direct and sort of abstract—she looks off her balcony and sees this tarp, this amazing Manhattan building and billowing giant construction barrier that’s a little bit loose… and then translates that onto the 2018 midterm election, through the title. And you said she first shared that video with her friends on a group text; the politics of the piece also seem related to that origin, the jump from an intimate, social image to something much larger—a big, airy installation.

MM: What’s interesting to me is how many people that didn’t know her, that just knew her work, were so affected by her death. I think that that was always the great mystery of her work, how she tapped into something that was so personal by using things that felt very collective, very cultural.

What makes a Lutz Bacher? What made the piece Moskva feel like Moskva, for instance, when we lifted this lower row of pages because it was too organized? We said, let’s lift the lower row and make this more complicated and confusing. Then it started breathing. There was a moment where, installing that work, it felt like Lutz was alive again. That was an amazing thrill. But, I don’t know what makes that a Lutz Bacher. That was painful for me. I really wanted it to feel like Lutz was still here. And somehow we managed to get there.

TD: Some of her work feels very stark. That’s the tension with the personal aspect— where you’re looking at this cold kind of ready-made whatever, and you can read it that way. But that reading doesn’t account for the emotion of it.

MM: I’ve said it before—I think she’s a conceptual expressionist. She believed deeply in her responses to things. And that would be the piece. Part of what makes a Lutz Bacher is flying. The sense of taking flight or taking a risk is essential to her work. It has to be activated by a leap, by that gesture of throwing yourself into something and not knowing.

… shaky footage panning along the top edge of a European-style courtyard or museum plaza, several stories high; the sky is blocked off by blue nets…

TD: Is this a piece, the netting?

MM: It might well be. I don’t know. I’m not familiar with this exhibition.

TD: This is another place where, in your role as organizer, facilitator, I wonder if you feel the need to explain the work or frame it somehow, and how you negotiate that impulse with the way the work defies that explanation.

MM: Yeah, honestly, I don’t know that Lutz would be happy with me having conversations about this or my describing it. But this is a different situation where we are in an institution. And I guess I think of myself as an interpreter of her work. She invited me to do that a lot. And that’s how I position myself. x

Monica Majoli is an artist living and working in Los Angeles. She is a professor at UCI. Majoli would like to acknowledge the importance of Allyson Unzicker, Associate Director and Curator of the University Galleries, in facilitating the logistical elements of Bacher’s exhibition.

Travis Diehl is Online Editor at X-TRA.