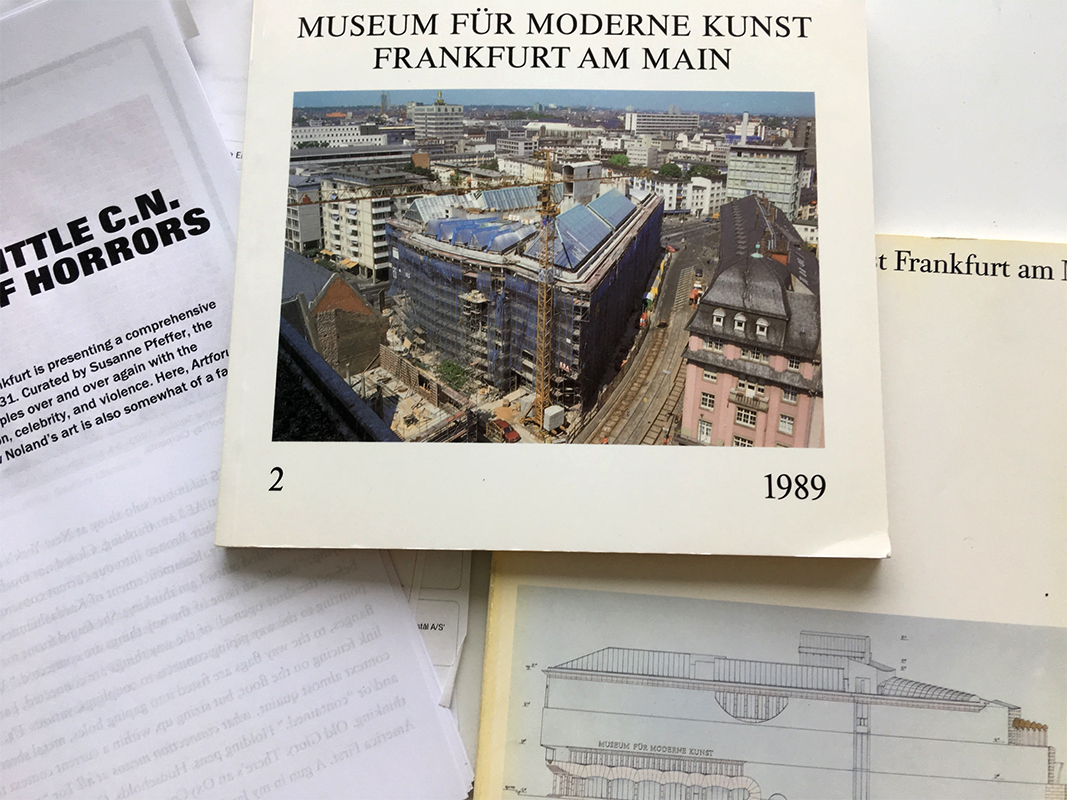

We went to Frankfurt—Travis from Los Angeles, Rasmus from Copenhagen—to see Cady Noland’s retrospective at the Museum für Moderne Kunst. We had to go to Cady, because Cady wasn’t going anywhere else. Maybe it’s simply another case of a US artist only getting their due in Germany. And maybe that has something to do with how naked and shriveled the US looks through that artist’s eyes. We stood in front of her tire swings and her stockades, her baskets of car parts and empty beer cans, her chain link fences, and watched Noland bore through western culture. Like a latter-day Jasper Johns, she describes the hypebeast of the American flag as queered normativity; the empty and the hole and the cage are her red, white, and blue. And from the show, onto the street and to the airport and beyond, exudes the kind of poison paranoia that makes a postmodern artwork of all Americana’s refuse—the sort of mindless, military-industrial generation by which the western world reproduces itself in 2018–19. Noland lives in New York, but Frankfurt was a homecoming.

Photo by Rasmus Røhling.

Travis Diehl: The Frankfurt School didn’t seem so crucial while we were there, I guess—but as we started to analyze “Frankfurt” in these sort of culture-industry terms, as a center for all sorts of international relationships, from the EU and the Eurozone to the US military presence in Germany, to banking in general, that Frankfurt School methodology seems unavoidable. I mean we were there to see an art exhibition, of all things.

Rasmus Røhling: Wait, you mean there’s no excuse for our ignorance? That contemporary art glasses are also, should always also be Adorno glasses?

TD: Maybe it’s a perfect excuse? That way of thinking—those glasses or that lens is such a default that we don’t need to name it, it’s just what we apply when we set out to analyze a big slice of culture.

RR: Hmm, Cady Noland doesn’t seem that Frankfurt-indebted to me. There’s the fundamental difference that she does not dissect but complicates and interlocks with a sense of resigned complicity, as opposed to the analytical exile feel. She recognizes it’s a theater of sorts, but one with no exterior.

Detail of Inka Meißner and Stefanie Pretnar in Province, Spring/Summer 2019. Photo by Rasmus Røhling.

TD: Right, I buy that. So what were we doing in Frankfurt? Dissecting? Vivisecting? Complicating?

RR: We were there to see Frankfurt, or to experience Frankfurtness accentuated through Cadyness.

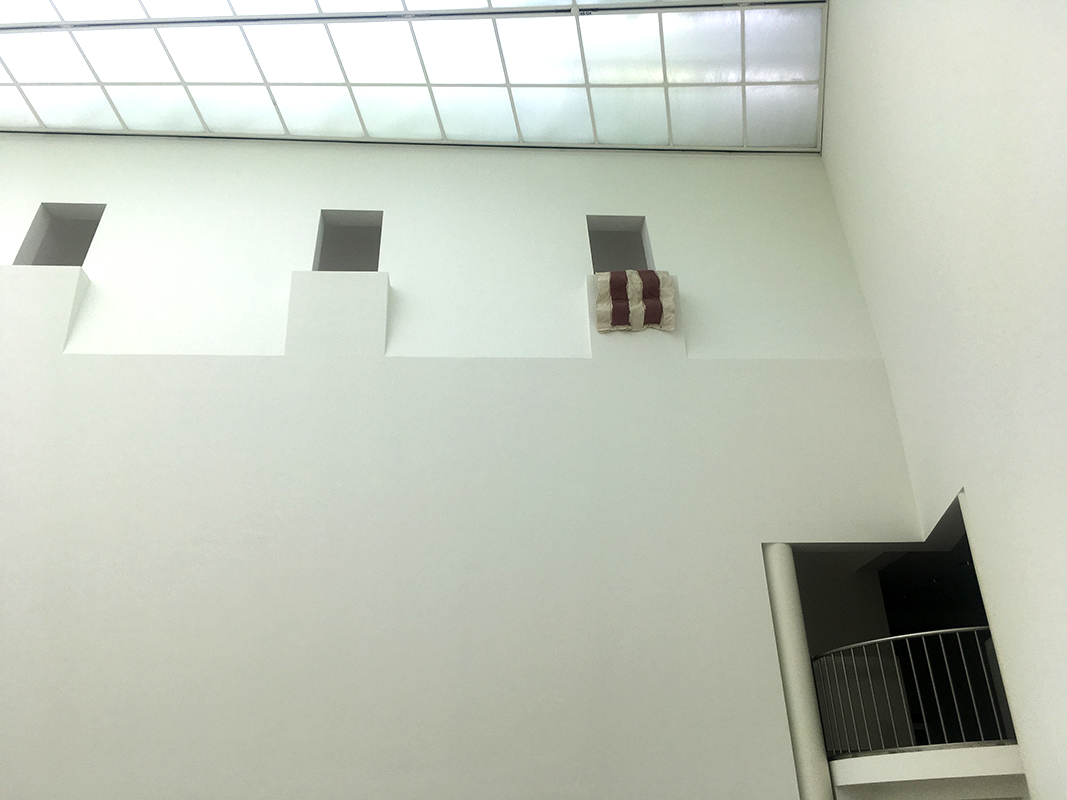

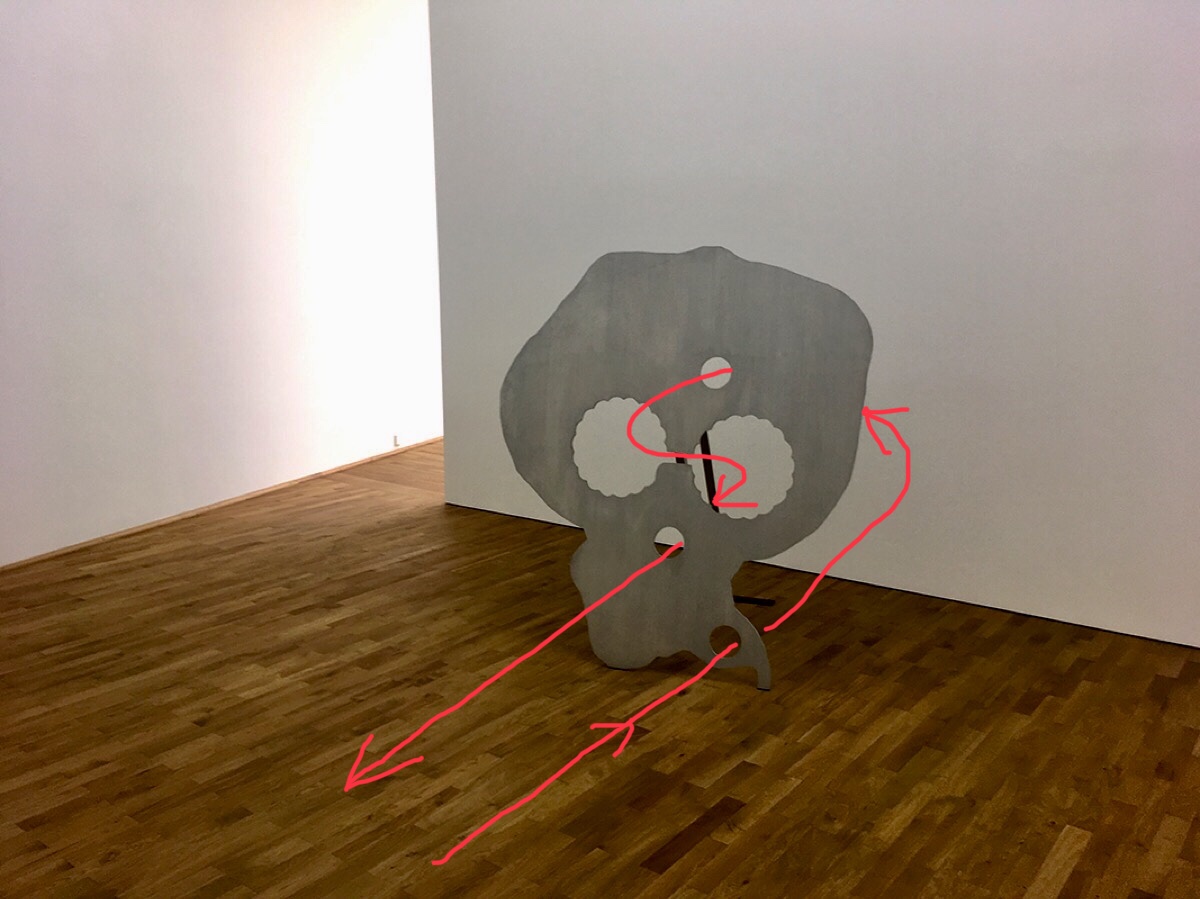

TD: Cadyness. Let’s try to put a finger on that. At least for me, the things that Cadyness transforms include the small circular windows and other geometric features of the MMK building, which start to echo the many “openings” in Noland’s work—the whitewall tires, the punctured standees, the Oozewald sculpture (1989, the image of Lee Harvey Oswald getting shot, reimagined as a kind of beanbag toss). So those formal things. But also the fact that Frankfurt is near a US military base seems Cadyfied. Her red-white-and-blue formalism is not at all limited to the exhibition. As you pointed out, walking around Frankfurt, the EU flag—it’s not simply a ring of yellow stars, but yellow stars gathered around a hole… Maybe the question is, where does Cadyness end?

Headquarters of the European Central Bank in Frankfurt. Photo by Travis Diehl.

RR: Maybe what determines that boundary is our paranoia. It’s like the beanbag Lee Harvey Oswald and Vito Acconci’s holed 9/11 proposal for a new World Trade Center, or the grommeted Jesus I keep talking about, with premade stigmata—something or someone that anticipates its fate or recognizes it simply as a function, hence adopts a utilitarian design.

TD: So paranoia is practical, on some level. But it goes beyond a kind of rational awareness of the possibilities, to the point of self-inflicting wounds before anyone or anything can wound you.

RR: Bruce Hainley points out how Cady makes a case out of how things are connected, “the way flags are fisted into gaping holes.” I think the other side of that argument that Noland is putting forward is the more cynical outrage that the victim’s body in a weird way was waiting for “fitting” the serial killer’s knife. Jesus was made for that super-duper Cadyness object, the cross; Frankfurt was asking for Cady. I guess an instrumentalization of violence: our society is becoming more and more full of such grommets, beanbag glory holes for bullets and planes to pass through. Rigging it with those is what we consider one of the virtues of preserving democracy. The flag for the next union will have pre-made holes in it. Like pre-distressed jeans. The transformation of something from a penetration to it becoming a passage.

Photo by Rasmus Røhling.

TD: That’s interesting—so many of the symbols or motifs that Noland uses, ie. beer cans, car parts, US flags, read as quintessentially American or quintessential Americana, but I hadn’t thought of the holes themselves that way. It’s like accepting mass shootings as an unavoidable side effect of gun rights… Noland formalizes these things—violence, penetration, a wound, becomes “a hole”…

RR: Yes. What does it mean when a society moves from seeing massacres as a violent penetration and instead as necessary collateral damage, a passage we have to endure in order to preserve democratic freedom.

TD: But—why Frankfurt? The simple answer is that the Cady Noland show didn’t travel… not to the US, not to anywhere, which was odd at first, since she is such an American artist… or at least, an artist that formalizes a certain critical patriotism… Why didn’t this show happen on Cady’s home turf? Why couldn’t it happen?

RR: Regarding Cadyness, we went there for the show and stood in front of the EU central bank tower and looked at the flag and the constellation of stars; all we see is a gaping hole. It’s once removed from the original “habitat” that you see the holes.

TD: It’s the hole at the center of the EU.

RR: Post-war Frankfurt was a cavity that needed a U.S. presence to fill it. For some reason that made me think of Michael Heizer’s Munich Depression (1969) and of Double Negative, in the Cady light…

Also kinda related/not related: Last week I was in Vienna and I sat next to a woman at a dinner who is doing her Ph.D in art theory. Turns out she is from Wiesbaden, just to the west of Frankfurt, and her childhood home always had Americans from the military base as neighbors. It was like living in Texas, she said. They would always just have come back from some air raid in Iraq, be BBQ’ing and telling stories. She said that now when she goes back to visit her mother and takes out the trash etc. the Americans are less talkative. “All they do now is fly drones,” she said.

Claes Oldenburg, Bacon/Carpet, 1991. Paint on stuffed canvas. Installation view from Cady Noland at MMK, Frankfurt, October 27 – May 26, 2019. Photo by Travis Diehl.

Charlotte Posenenske, Vierkantrohre, 1967. Hot-dipped steel plate. Installation view from Cady Noland at MMK, Frankfurt, October 27 – May 26, 2019. Photo and alterations by Travis Diehl.

TD: Okay, now we’re really taking the red pill, but her work also anticipates the Twin Towers, 9/11—that absence. Or maybe our paranoia retrospectively puts that in there? And yet… The several pieces by other artists that the MMK included with Noland’s work, the way they do—the formal riff there was twinning, pairs. The small Michael Asher plaques, there were two; the Charlotte Posenenske piece was two vertical sections of conduit. Even the Oldenburg soft bacon piece was draped through a window in a way that resembled the towers.

RR: Ha! True.

TD: I mean, I looked—there was a Cady Noland piece in Peter Eleey’s September 11 show at MoMA. The conceit of that show’s catalog is that every plate of the artwork appears twice, doubled, on both sides of each spread. When something like a beer can becomes a formal element, a note in the composition, then the paranoid reading can really take hold. Which, like they say—just because it’s paranoid doesn’t mean it’s not true.

RR: Posenenske is from Wiesbaden.

TD: Oh wow.

RR: I think I said this before but Leo Steinberg has this point in his infamous Sexuality of Christ essay (1983) that Byzantine art labored to convince us of God’s divinity in the Christ Child, while in Renaissance art this paranoia or suspicion came true, was successfully designated, and our job is simply to enjoy its manifestation in the work of the Renaissance masters. We are here to enjoy the paranoia.

TD: I keep thinking about the phrase, “Basket of Action,” that Cady titles so many of the basket pieces with—it evokes its own specific episodes of sexual assault from the last few years. The brutality of abstracting any sort of violence, like manufacturing or sports or sex or even rape—all are “action.” “Sometimes I had too many beers. Sometimes others did. I liked beer. I still like beer. But I did not drink beer to the point of blacking out and I never sexually assaulted anyone.”

RR: Brett Kavanaugh. Maybe it’s all a kind of played-out plot. Like, thinking about Kennedy I constantly see that chart or graphic of the magic bullet going through his skull.

Cady Noland, Cowboy Bullethead Moviestar, 1990. Aluminum plate, metal stand. Installation view of Cady Noland at MMK. Photo and alterations by Travis Diehl.

TD: The Oozewald sculpture is so visceral. You really feel that this is a picture of somebody being killed. On one side of that, you have the Warhol “Death and Disaster” painting of the car crash, in white, from the MMK collection. On the other, there’s Cowboy Bullethead Moviestar (1990), the Cady sculpture that resembles a skull, a standing aluminum plate, with holes cut in it, and it’s supposed to be… what, a composite of a cowboy, a butterfly, an ink blot. Something else? In that piece, it’s like whatever bullet Cady is shooting has ricocheted off of her other references and motifs to create this perfectly monstrous form, a violently abstract minimalism.

RR: I really liked that piece. To me that crowns her logic of turning images into flesh. Any typical authoritative museum voice saying that this can of Budweiser is a signifier of violent consumerist America somehow falls short, it misses an eccentric essence that it is always from the perspective down here in the mosh pit of everyone’s fear, everywhere and nowhere-America, where the outrageous idea of a violent can of Bud makes sense. Which is why the Hainley essay makes sense in that he takes on this noiresque talking-to-oneself way of reasoning. It works with Noland’s paranoid approach.

TD: Is he performing that paranoia, do you think? I mean, to me—Frankfurt School glasses aside—there’s something inherently paranoid to criticism, full stop—this sort of unspooling critical analysis that doesn’t conclude, more like exhausts itself.

RR: Yeah. What’s the difference between when Cady Noland or the Coen brothers or Group Material engage in the idiosyncratic limbo of exercising/exorcising Americana?

Photo by Travis Diehl.

TD: That makes me think of another moment—I think we both had this moment—of finding the Lichtenstein drawing on the upper floor, on the wall across from a few Noland fence pieces, and realizing that, oh, it’s actually a Sturtevant drawing. And then it seemed like it could only have been a Sturtevant drawing; a first-degree Lichtenstein would have been lacking.

RR: It’s very important that to raise this fear you must preserve the normative harmless, jovial face value of these objects—that in order to animate that “language of evil” you need to preserve the idea that it is braided into the golden retriever naivety and optimism of the regular patriotic tongue.

TD: Well but, maybe it’s just you—“you” the hypersensitive paranoiac liberal. Maybe she just likes beer. What a world! Wouldn’t it be nice if the worst thing about an empty beer can were that it’s empty.

RR: No, it’s also Diedrich Diederichsen. At this Cady symposium at MMK he talks about how the scary thing about serial killers is their tools. Just regular stuff you can buy at Home Depot. In that way Cady needs the normative, relies on it, to create her alternative language through it.

TD: Normativity is her formalism.

RR: Though the claim is that that message is inherently there all along.

Cady Noland, Oozewald, 1989. Silkscreen ink on aluminum, American flag, Coca Cola drinking cup, metal stand. Installation view of Cady Noland at MMK, Frankfurt, October 27 – May 26, 2019. Photo by Travis Diehl.

Cady Noland, Oozewald, 1989. Silkscreen ink on aluminum, American flag, Coca Cola drinking cup, metal stand. Installation view of Cady Noland at MMK, Frankfurt, October 27 – May 26, 2019. Photo by Travis Diehl.

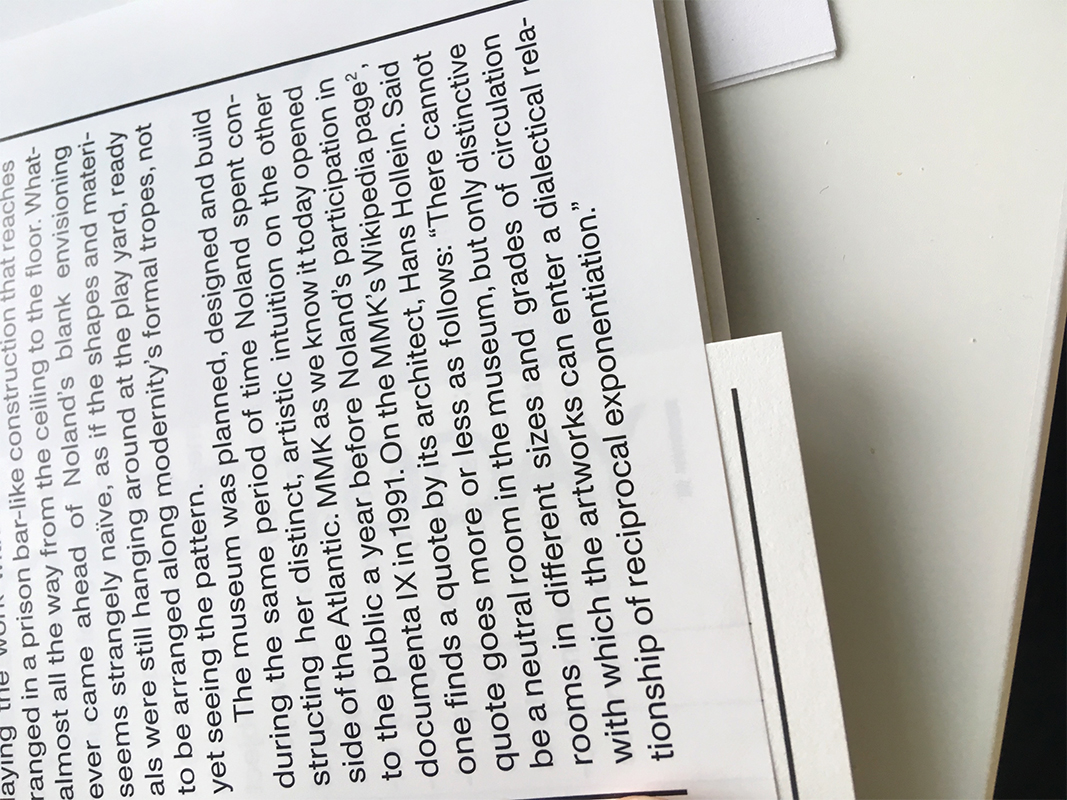

TD: The other thing about the Hainley piece is that he writes it twice—there’s an essay, “The Picture of Little C.N. in a Prospect of Horrors”—and then in the summer Artforum there’s a longish review, which actually begins by revising the previous essay: “On second thought…” He shifts into review mode—instead of the refrain, “I was thinking,” it’s, “What was she thinking?”

RR: But that’s perfect. To me that really follows this film noir approach, “post-war American woman as a self-complicating subject that needs male agency/Raymond Chandler type detectives to resolve them.” (Jon Wagner said that, just about, once. Polemically.)

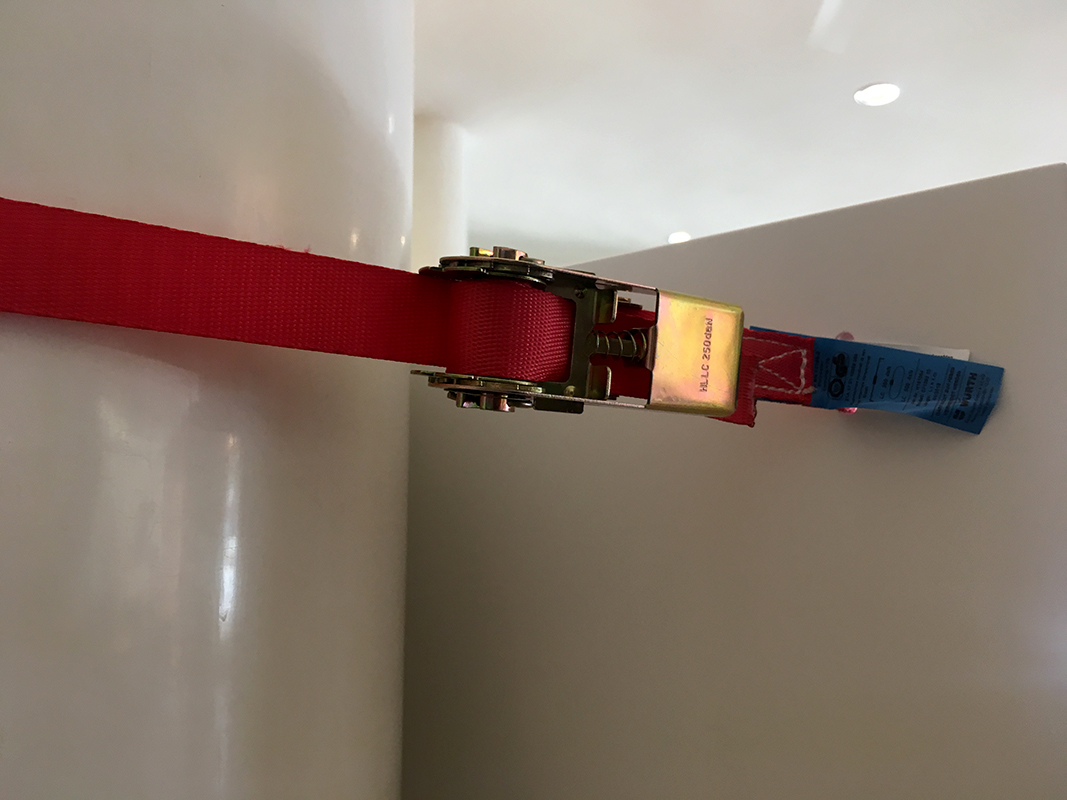

TD: Does Cady need a self-narrating male detective to resolve her? Is that what Bruce is doing? Is Frankfurt the seat of normativity? Or normalcy, stability? I mean, again, I don’t find the idea of “Gotcha! It’s violent”—this kind of prankish revelation—totally satisfying. It’s more about the paranoia that that “trap” induces, which really starts working once you’ve exceeded the Cady Noland show, once your analysis seeps out of the exhibition… out of that postmodern moment and into this one. There’s that white sign strapped to a column in the MMK lobby, for example, with red straps with blue tags.

Photos by Travis Diehl.

RR: Hainley has a sort of chain explanation for the development of that process as “fitting -> fisting,” which I think makes perfect sense, but which is a logic that is by default personal. It must be experienced on that level. If the museum implements “fisting” in its “objective” description, it somehow fails.

TD: There are a couple of institutional choices that have that kind of invective, that operate on the level of personal collision—one is the inclusion of the Kenneth Noland painting at one end of the show (which is the first illustration in Hainley’s review, a shot through the vertical bars of a Cady piece to the Kenneth piece beyond.) There’s an obvious Freudian thing there, the postmodernist daughter filtering our view of the modernist father. And one thing that struck me about the Kenneth Noland was the palette—it’s green and orange—exactly the two colors that Cady almost never uses. (With one exception, Model with Entropy, 1984, one of the earliest works in the show.)

RR: But if we really are to follow the Cady logic that American culture is an inherent, self-suppressing language which eventually, self-evidently will show its evil nature simply by doing its American thing, then Cady is really, as Bruce puts it: Tanya as Bandit, the girl gone wild, the daughter of the other Pollock—what was she thinking…

TD: Uh-huh. I almost wrote, “Is she a serial killer, asking to be caught?” There’s something fatherly/daughterly about the idea of her “coming home” to Frankfurt, which was never her home. But is there more to it than one movement or generation surpassing the last? Is that what you meant by your phrase, “No Confidence Cady”?

RR: I was thinking of Jeremy Corbyn stating the No Confidence vote against Teresa May, like the chainmail of democratic old Europe was falling apart—Cady’s show on how it’s all connected made so much sense in that moment.

Cady Noland, Museum für Moderne Kunst, Frankfurt, October 27, 2018 – May 26, 2019. Installation view. Foreground: Cady Noland, Dead Space, 1989. Scaffolding pipes. Background Center: Kenneth Noland, Touch, 1963. Acrylic on canvas. Background Right: Steven Parrino, Bent Painting, 1991. Enamel on honeycombed aluminum. Courtesy the artist and MMK, Frankfurt. Photo by Axel Schneider.

TD: Yeah, exactly—adding “Cady” on there redirects that vote against pretty much the whole establishment—so that Corbyn indicts himself, too. Labour Party Dad and all his friends. Believers in the benevolence of formalism. A whole generation that insists that painting is just, like, painting. A kind of queering of the old order.

RR: I don’t know too much about Noland, Sr.’s work, but to me it seems like he was sincerely into exercising the expression/affect of painting without engaging in the bad trip of virtuosity and stroke-making. Like he tried to enter painting from the back—to stab it in the back and have it bleed through onto the canvas. Voila. To me there is an antagonism towards the way things are done, towards what constitutes an image, the process of an appearance, that’s similar to Cady’s approach.

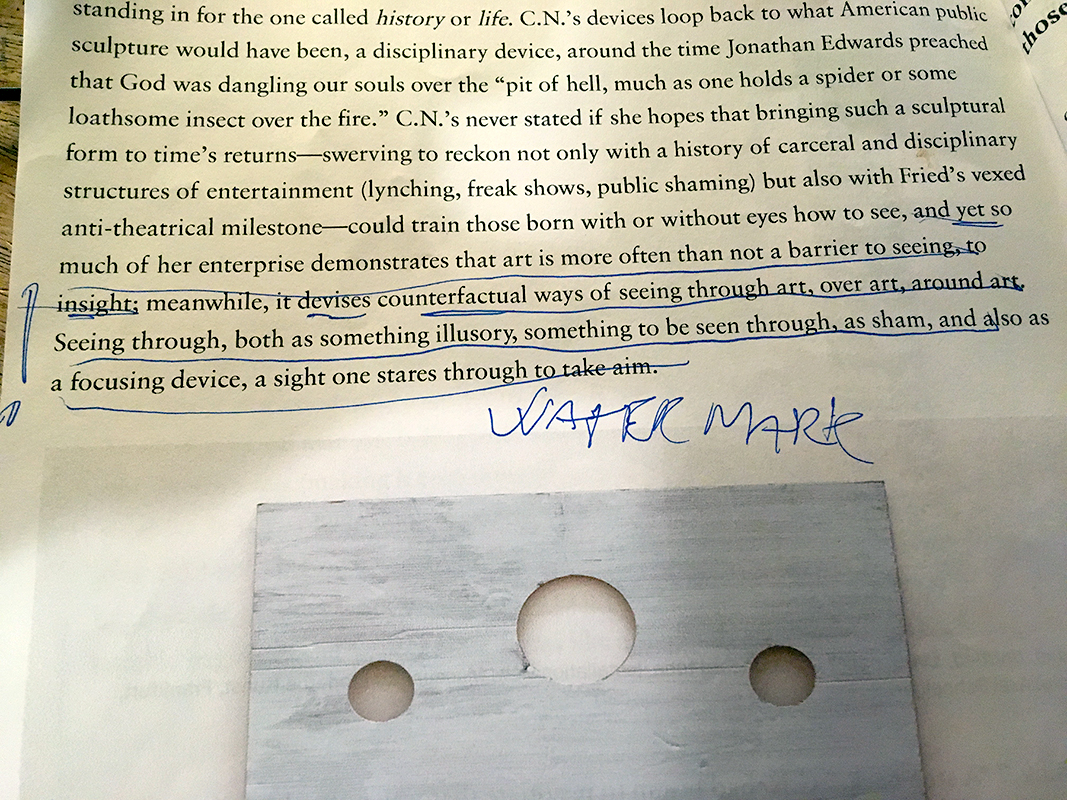

There’s this watermark logic to Cady’s work. You kind of have to ignore the initial image/motive to see the watermark (which is her whole infused paranoid violence take on it), the way you see through a dollar bill to the watermark which really authenticates it. Or like those lame 3D pictures of the early ’90s (actually) where you have to zone out and not focus on this pseudo psychedelic pattern and suddenly there’s a dolphin. And Hainley also touches on this with his whole point about a way of training “those born with or without eyes to see.” I feel like that’s going on in Cady.

TD: To put a hole in something. To resist (falling into) the hole. To face the hole.

X

Detail of Bruce Hainley, “The Picture of Little C.N. in a Prospect of Horrors,” Artforum, January 2019. Photo and alterations by Rasmus Røhling.

Rasmus Røhling is a Danish artist, educated at the Jutland Art Academy, Aarhus (2008) and the California Institute of the Arts, Los Angeles (2010). Røhling has previously exhibited at Primer, SixtyEight Art Institute, and Den Frie Udstillingsbygning, Copenhagen; Sismografo, Portugal; Artist Space, New York; Metro PCS and Human Resources, Los Angeles; and Museum Fur Gegenwartskunst, Basel; among others. Rasmus would like to thank Benedikte Bjerre and John Skoog for their invaluable Frankfurt as well as Noland insight.

Travis Diehl has lived in Los Angeles since 2009. He is a recipient of the Creative Capital / Andy Warhol Foundation Arts Writers Grant (2013) and the Rabkin Prize in Visual Art Journalism (2018). He is Online Editor at X-TRA.