For Dispatches, Rasmus Røhling samples Chadwick Rantanen’s Bun (August 27–November 5, 2022) at the Institut Funder Bakke, a former painting studio in the Danish wilds of Jutland.

From Roman militarism Christianity did take the device of the standard, or trophy of victory. But where the Roman sign elevated a bird of prey, the Christian trophy holds up the scaffold on which a man condemned underwent crucifixion.

–Leo Steinberg

Please for the love of buns, pre-order on hartbageri.com.

–Hart Bageri

If we can just, just bear the cross, yeah.

–S

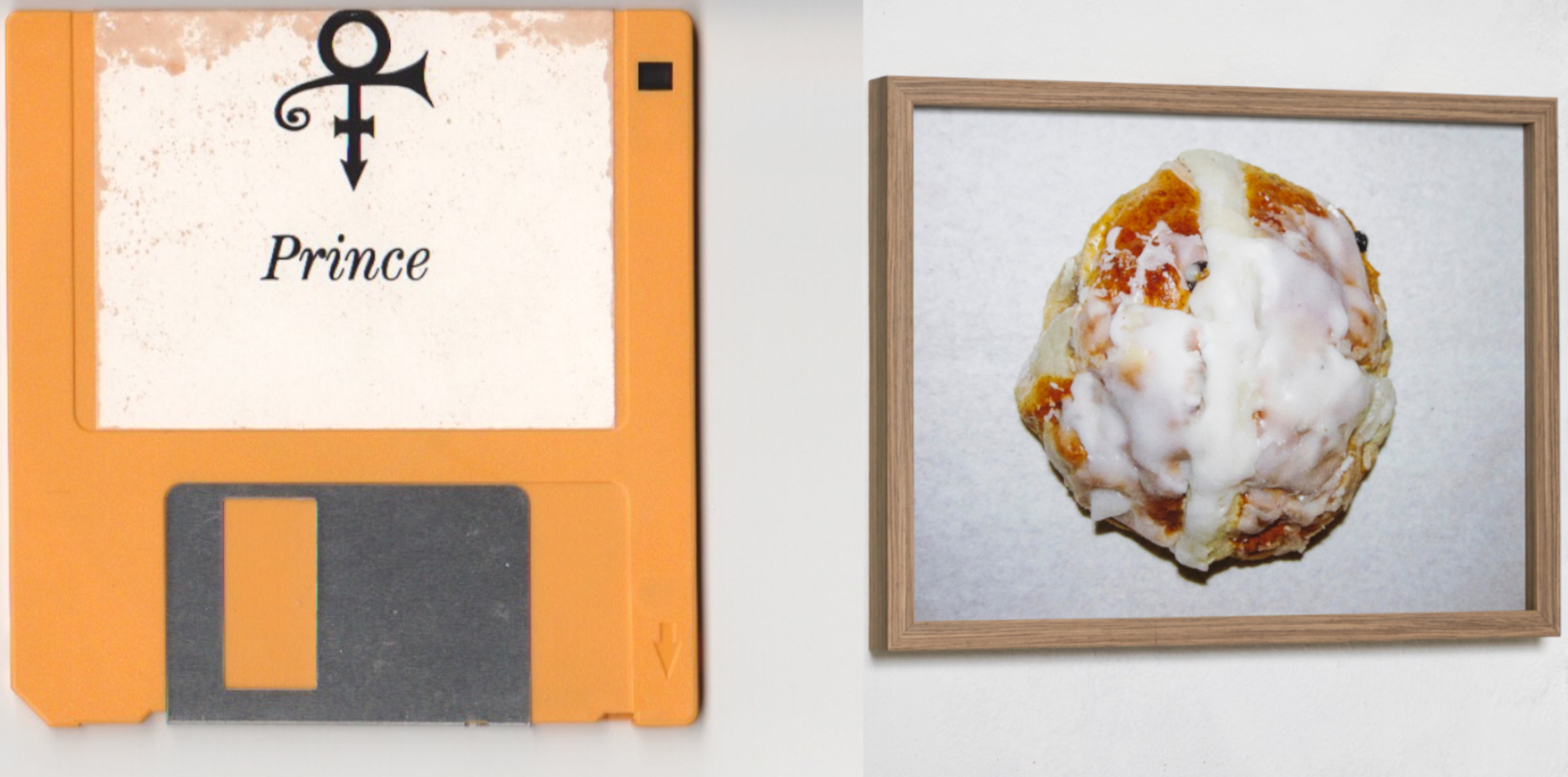

Chadwick Rantanen, Nom, 2022. Archival pigment print, walnut frame, 20 ¾ x 15 ¾ x 1 ⅛ in. Installation view, Bun, Institut Funder Bakke, 27th August 27–November 5, 2022, Denmark. Courtesy of the artist and Institut Funder Bakke. Photo: Malle Madsen.

At once emboldened and biased by his upbringing as a Jehovah’s Witness, as well as by art school’s indoctrinaire obsession with the good old signifier/signified discrepancy, Chadwick Rantanen seeks out the most unworthy type of Protestant Americana as a vehicle for his take on Christian iconography: hot crossed buns. As the godhead originally contaminated the perfection of divinity by assuming flesh, Rantanen seemingly degrades his substance by replacing Patti Smith and Shaker trance with the current mass appeal of The Great British Bake Off in order to rock his religion.

Bun, installation view, Institut Funder Bakke, 27th August 27–November 5, 2022, Denmark. Left: White Ribbon, 2022. Archival pigment print, walnut frame, 20 ⅞ x 17 ¼ x 1 ⅛ in. Right: Press Fit (Staircase), 2022. Laser cut plywood, 2 x 2 ¾ x 2 ⅜ in. Courtesy of the artist and Institut Funder Bakke. Photo: Malle Madsen.

Unfolding at the self-institutionalized Institute Funder Bakke in a semirural corner of the tiny kingdom of Denmark, Rantanen’s Bun consists of ten framed photographs of hot crossed buns and six idiosyncratic installments of laser cut miniature models of staircases and ladders. From the megalomaniac realm of gaming tables, model trains, and “ehh architecture,” these “press fit” sculptures rely on the same jointing principle as the crucifix. In another life, these structures could be mini Sam Durant gallows or Midwestern Mike Kelley’s educational complexes—but they’re not. Made from tiny plywood, they have a kind of quantitative, Doozers-from-Fraggle-Rock insignificance to them, which seems to be the point. They’re hung in the manner of crucifixes, but these crucified crucifix-like constructions don’t reach the high courts of iconicity, as if they’re in line at a crucifix audition for a role they won’t get.

Bun, installation view, Institut Funder Bakke, 27th August 27–November 5, 2022, Denmark. Courtesy of the artist and Institut Funder Bakke. Photo: Malle Madsen.

The images of buns are all found on the internet but have had their crosses digitally reduced to single lines, so as to sync with the Jehovah’s Witness doctrine of 1936 onward that, per the press release, rejects “the idea that Jesus died on a cross, and instead teach[es] that he died on a single wooden stake (crux simplex).” Through this virtual sanitation, Rantanen flirts with the ancient role of the iconoclast. In doing so, however, he seems to deliberately defy the usual ironies of the religiously motivated destroyer of icons who, in their attempt to correct or cancel an image, often make the fatal mistake of considering themselves external to the overall mosh pit of representation. Rantanen seems hyper aware that this infamous clash with an image is really a kind of copulation, one that always breeds new, bastard iconicity.

Left to right: Kader Attia, Culture, Another Nature Repaired, 2014–2020. Chadwick Rantanen, Baking Cooking, 2022. Archival pigment print, walnut frame, 20 ¾ x 15 ¾ x 1 ⅛ in.

As the cutting operation in photoshop is often 10% about the incision and 90% the restorative aftermath, one could assume that, in this attempt to enforce Jehovah’s Witnesses’ revisionist thought via the Adobe suite, those poor buns would come out somewhat scarred—would bear the all too familiar Francis Bacon-like aesthetic of a GAN algorithm scrambling to come up with a realistic image or face, or at least have a distinctly repaired, Kader Attia look to them. Instead, the fresh baked panfuls of iconicity Rantanen serves us, covered by museum glass, appear demonstrably flawless, altered with absurd, almost perverse care and attention so as not to leave any Matrix-like tears in the mundane breadbasket reality in which these buns reside.

Rantanen did a similar exhibition (photos with digitally modified crucifix appearances and laser cut models of stairs and ladders) for a show at Bel Ami in Los Angeles earlier this summer. For the Denmark version, however, he altered the franchise from depictions of various cases of stigmata manifested in gross homes on the internet (plus a fluffy bunny) to fluffy glazed buns exclusively. Did he do this to display a kind of site specific awareness? Did he choose those enriched yet helpless Wonder Bread-ish lumps knowing that this pale outpost in the hinterlands of the Essex Street sphere is the very epicenter of the raging gastro decadence—where the whole sourdough renaissance began? And if so, is this an attempt to have American dreams and depravity clash with Danish welfare, a kind of Nomadland goes noma-land? At this point, do gentrified western democracies even care about pagan pastries and their latent Bruegelian symbolism?

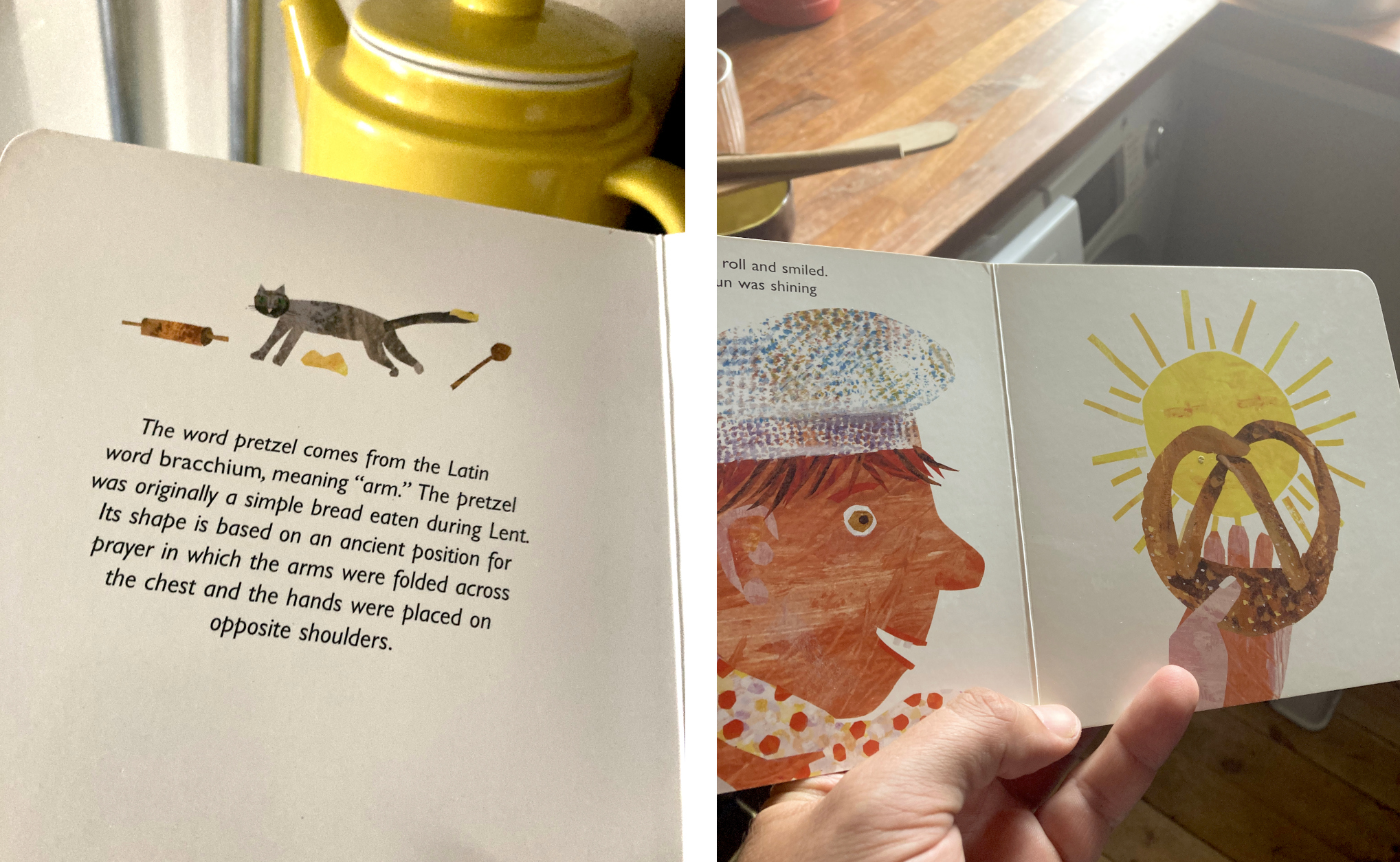

Eric Carle, Walter the Baker, 1972. Details of interior. Photos: Rasmus Røhling.

In Eric Carle’s Walter the Baker, to avoid being banned from the Duchy, Walter has to come up with a new pastry, and by accident, as he throws a fit (and the dough), invents the pretzel. Walter presents this to the Duke and Duchess and voila! The salty dough reflects both Lent and the post-reformation modesty of Lutheran Europe; plus the pretzel posture mimics the position of a person in prayer—hence, Walter’s invention succeeds both as gimmicky pastry and cultural signifier. Today, however, if Gordon Ramsey—no, better: René Redzepi—were to present a similar invention to, say, Duchess of Scandiland Björk, or Greta Thunberg, unless it had yuzu-cream filling, almond flour, and resembled a hashtag or a downward dog, no one would give a shit.

Left to right: Vintage floppy disk containing custom Prince font. Chadwick Rantanen, Frosted, 2022. Archival pigment print, walnut frame, 20 ¾ x 12 x 1 ⅛ in. Installation view, Bun, Institut Funder Bakke, 27th August 27–November 5, 2022, Denmark. Courtesy of the artist and Institut Funder Bakke. Photo: Malle Madsen.

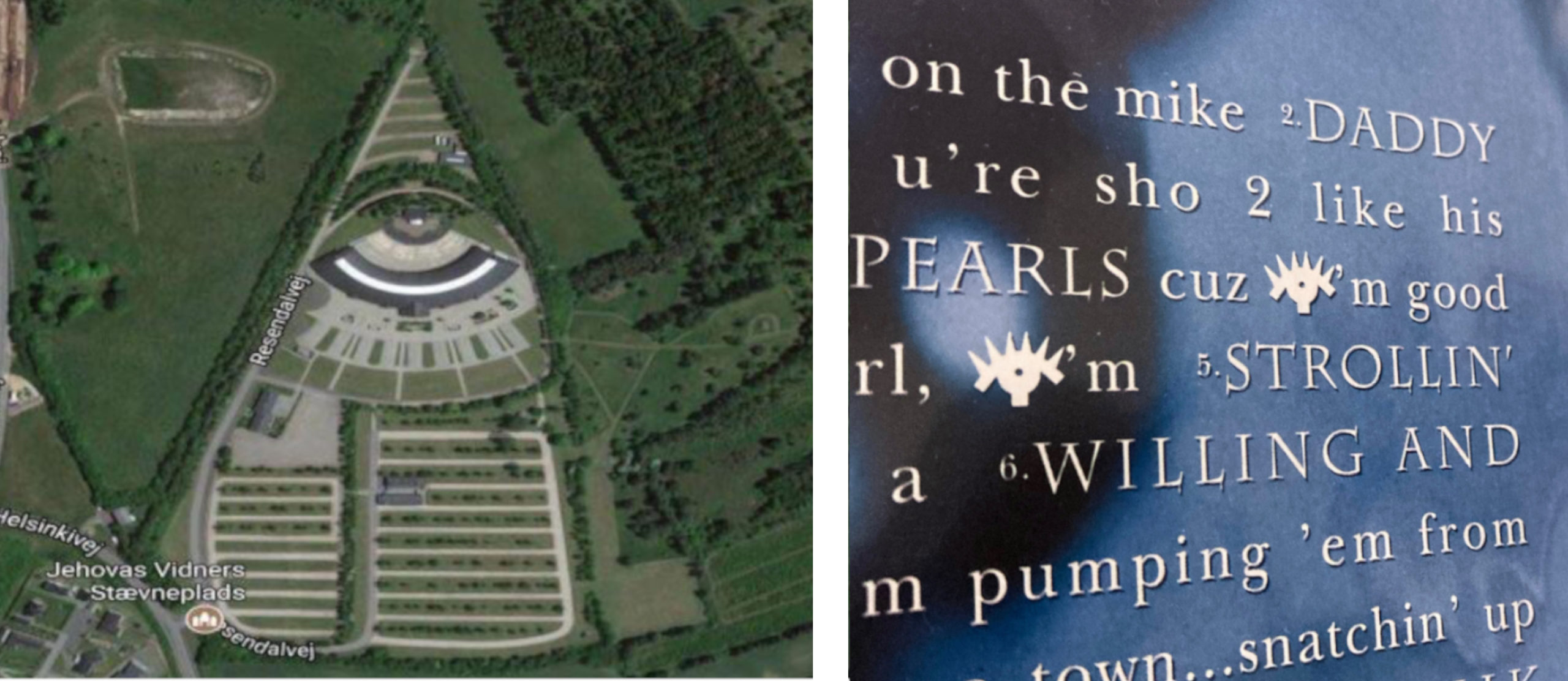

After the opening, Chadwick was upstairs on the phone most of the evening, trying to get his flight the next morning redirected to Minneapolis, as he’d managed to book a tour at Paisley Park. Giving in to Ratanen’s pareidolia trip—and given the fact that literally a stone’s throw from the exhibition is the Jehovah’s Witnesses’ Danish equivalent to the Hollywood Bowl, “Jehovah’s Vidners Stævneplads,” where they hold annual rallies for the entire Scandinavian congregation—I couldn’t help thinking about Prince as a kind of crossed bun himself, the embodiment of divinity and kitsch: Brother Nelson, as he was simply known among his fellow Witnesses; and at the same time that weird “The Artist Formerly Known As” glyph on a yellow floppy disc mailed to journalists; a crucifix of sorts that precedes the crucified, and ironically—sadly—a symbol that ended up folding in on itself due to complications related to a joint condition.

Left to right: Jehova’s Vidners Stævneplads, Jutland. Satellite imagery © Google Maps. Prince and the New Power Generation, Diamonds and Pearls, 1991. Detail of back cover. Photo: Rasmus Røhling.

Perhaps at this point in our visual economy, where the fundamental premise of the Sign “☮︎” the Times is exactly its disjointedness, it seems we sometimes put up Jesus or Prince or Greta et al. not in front of but somehow behind the cross, so that the stigmatization ends up blanking out the stigmatized subject, and prevents us from having the full Passion á la Mel Gibson experience. According to the press release, “A line makes for a weak symbol. It is too brutal and ill suited to ideology. It is more commonly used as a division or component, not an end in itself.” Maybe what Chadwick the Baker was getting at was a new and improved, jointed set of censor bars—a swollen and absurd crosshair in the rifle scope that ultimately prevents the sniper from the kill—before tossing that doughy sign around in photoshop until its arms fell off. x

Bun, installation view, Institut Funder Bakke, 27th August 27–November 5, 2022, Denmark. Courtesy of the artist and Institut Funder Bakke. Photo: Malle Madsen.

Rasmus Røhling is an artist living in Copenhagen.