The Dash column explores art and its social contexts. The dash separates and the dash joins, it pauses and it moves along. The dash is where the viewer comes to terms with what they’ve seen. Here, Alec Recinos considers the common brick as the lodestone for anti-institutional conflicts across time and space, and wonders how we might use its simple formalism against the old structures it supports.

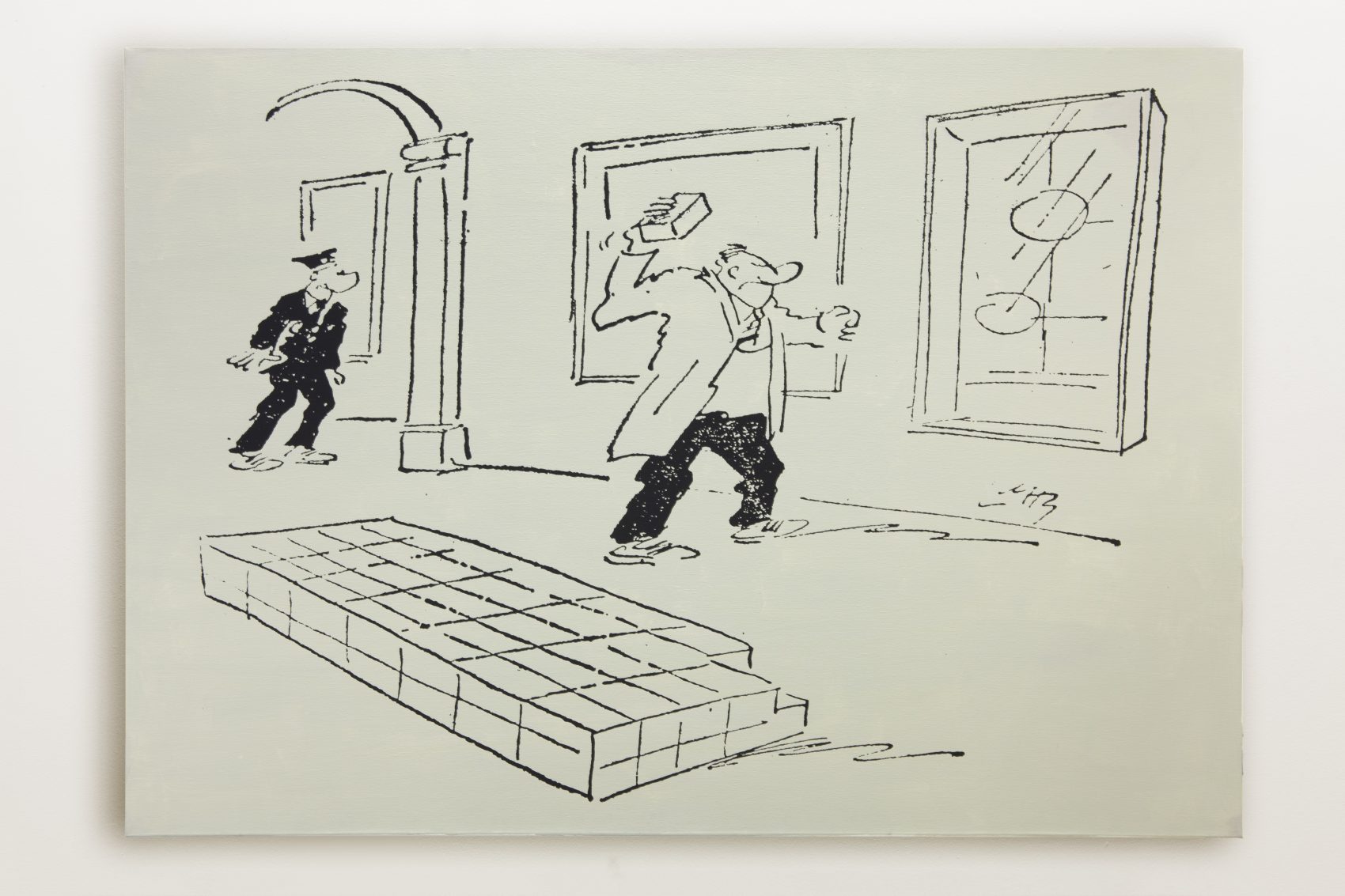

Claire Fontaine, Untitled (Throwing Bricks), 2012. Acrylic and silkscreen on canvas, 55 7/8 x 78 3/4 x 1 1/8 in. © Claire Fontaine. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Florian Kleinefenn.

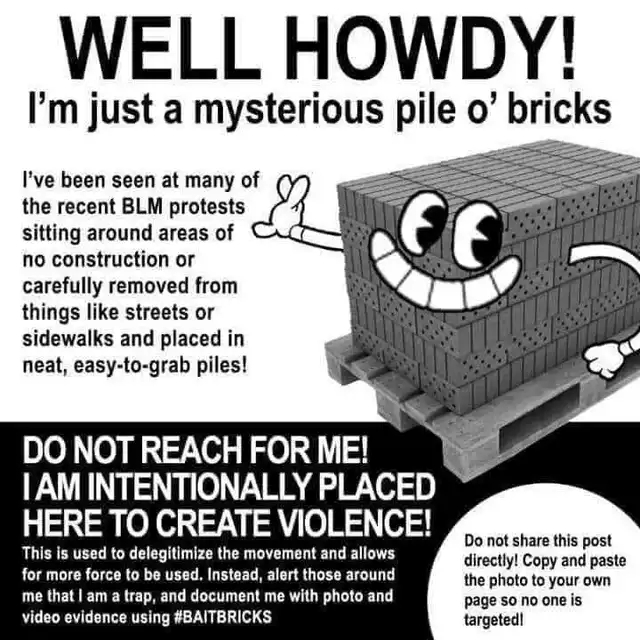

With so much on the line, it’s hard to believe that anyone cared about a stack of bricks. In a year already marked by excessive death from the coronavirus pandemic, the police murders of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor, among so many others, sparked protests and riots throughout the United States. People took to the streets, marching, declaring autonomous zones, looting—even burning the third precinct of Minneapolis. As images and intel ebbed and flowed on social media, one notable rumor took hold in the collective imagination: bait bricks. Memes and posts alleged that police had planted pallets of bricks at protests in order to tempt protesters to turn to violence, thus providing an excuse to shut it all down with excessive force. To avoid this trap, the memes implored everyone to resist any escalation and refuse to stray from the well-worn path of nonviolent demonstrations.

Bait bricks meme, 2020.

Step back more than forty years to the United Kingdom to encounter another stack of bricks at the center of a very different sort of country-wide upheaval. In February 1976, the investigative journalist Colin Simpson published an article for the Sunday Times titled “The Tate Drops a Costly Brick,” excoriating London’s contemporary art museum for their acquisition of several artworks, chief among them Equivalent VIII (1966): 120 firebricks arranged on the floor in a configuration six bricks wide, ten bricks long, and two bricks tall.1 Though the museum’s purchase had actually occurred several years before, and the work had been exhibited without any objection, Simpson’s broadside sparked a months-long national scandal in the UK, inspiring hundreds of articles in newspapers and tabloids that attacked the Tate for spending taxpayer funds on what was evidently worthless, nothing more than “a pile of bricks,” and culminating in the vandalism of the artwork by an incensed chef.

Carl Andre, Equivalent VIII, 1966. Firebricks, 127 × 686 × 2292 mm. © 2020 Carl Andre. Licensed by VAGA at Artists Rights Society (ARS), NY and DACS, London. Photo © Tate.

Separated as they are across time and space, both piles of bricks are still connected. Setting aside their formal similarities for a moment, what binds the two together is the way they structured their respective situations and reified a strange tension at their cores. Bricks, for the British public, materialized the animosity of the institution, which absorbs the building blocks of daily life only to spit them back out again in an unrecognizable, hostile form. For the protesters in the US, bricks brought focus to what was at stake in their demands, making the asymmetries of violence impossible to ignore and evincing the need to extend the fight for abolition to the elements at the very root of society. Even as they anchored these protests, however, both piles simultaneously provoked a conflicting force, producing in each situation a direct opposition between the protesters’ desired outcome and the logic that structured their demands.

Though baseless, the bait bricks conspiracy recognized the unavoidable truth of police violence and retaliation. In so doing, however, the theory also framed the police as an all-powerful force capable of manipulating everything and everyone, implying that the protesters’ explicit demand to abolish the police is a lost cause. It entered into a discourse of “legitimacy” that enforces the ineffective norm of peaceful, police-sanctioned protest and stigmatizes those who take up other tactics. Evoking an insurmountable adversary and pressuring protesters to stick solely to symbolic methods, the bait brick memes traded the movement’s momentum for a sense of paralysis. The stacks of bricks remained undisturbed on the roadside, yet they were nevertheless deployed—against the protesters, frustrating what could have been.

In the case of Equivalent VIII, the conflict arose between the public’s protest against what they perceived as out-of-touch elites and the vision of art that this criticism upheld. What so scandalized the British public wasn’t that the Tate had overpaid for an artwork—the public was not against art as such—but rather that they had spent so much money on something so profane: just a pile of bricks, mundane materials assembled without any evident artistry. They weren’t wrong—minimalism’s so-called “deskilling” in fact relied on and reinforced the power of institutions in order to be legible within the discourse of art. But although their encounter with the bricks laid bare the conservative tendencies beneath modernism’s radical posturing, they remained unable to follow this revelation all the way down. Instead, the public clamored for a return to the elitist aesthetic regime of the recent past, where properly good art was seen to be the product of individual genius and skill. Through their outrage, Britons ultimately belittled themselves through their denigration of the ordinary and championed an exclusionary beaux-arts innately at odds with any of minimalism or conceptualism’s “democratizing” impulses. Their protests effectively argued to maintain the gap between art and the everyday, ensuring that art remained the purview of the very elites they railed against.

Together, these two episodes frame a set of challenges facing contemporary struggles to transform the art world. In this particular microcosm, where the simplest material or gesture evokes the most radical theories, the brick’s ability to yoke politics and aesthetics is particularly relevant. Across many movements, ranging from decolonization to diversification, a similar set of contradictions seems to be at play, where initially liberatory impulses harbor antonymic tendencies. These immanent oppositions prevent each movement from untethering from the conventions of the status quo, and thus from further developing. As the desire for change remains predicated on the assumptions of the very system it hopes to destroy, any results remain strictly surface-level. In some cases, this may be better than nothing at all, but without fracturing the very foundations of art as it is today, any fundamentally new world remains out of reach.

Rafa Esparza, Figure Ground: Beyond the White Field, 2017. Installation view, Whitney Biennial 2017, Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, March 17–June 11, 2017. Courtesy of the artist and Commonwealth and Council, Los Angeles. Photo: Mario Vasquez.

Take, for example, the adobe brick artworks of Rafa Esparza. The artist has spoken of his engagement with museums and galleries as attempts at “browning the white cube” and destabilizing the white, colonial history that saturates the art world. In Figure Ground: Beyond the White Field, his contribution to the 2017 Whitney Biennial, Esparza built a curved structure in the museum out of handcrafted adobe bricks in which he exhibited artworks by the types of artists who have customarily been excluded from the galleries due to their ethnic identities, literally carving out a space for them within the homogeneous white walls. The piece does the work of producing a representational rupture, which has meaning to many: as Esparza recounts, his works with adobe brick tend to evoke a sense of nostalgia and belonging among many Latinx immigrants and communities. Such a gesture, of course, only makes sense when situated within the framework of the white cube. The work’s gambit can be seen as radical primarily because it brings differentiation to the institution’s logical structure. But although Esparza’s adobe bricks swap out the individual actors, broadening the terms of who can be included in the position of the artist, they can go no further, and ultimately shore up the system that structures their relations.

Return now to the formal connection between these moments: the brick. Bricks brim with potential, a pile of them especially so. They suggest a mass of possibilities, and reveal motivations. When you can do so much with a brick, why simply keep things the way they are? Yet despite this boundlessness, they often seem to embody an insurmountable inertia: to build, or to break—a dialectic without development. Even so, it’s no use to leave the bricks alone. As a bricklayer said of Equivalent VIII, “Until you do something with it, it’ll always be a pile of bricks.” Perhaps it’s time to take the bait. X

Alec Recinos makes work.