The Dash column explores art and its social contexts. The dash separates and the dash joins, it pauses and it moves along. Here, Isabelle Bucklow considers how early videos by Joan Jonas preempted the fragmented identities of the Zoom workplace by decades—and how they just might help us survive.

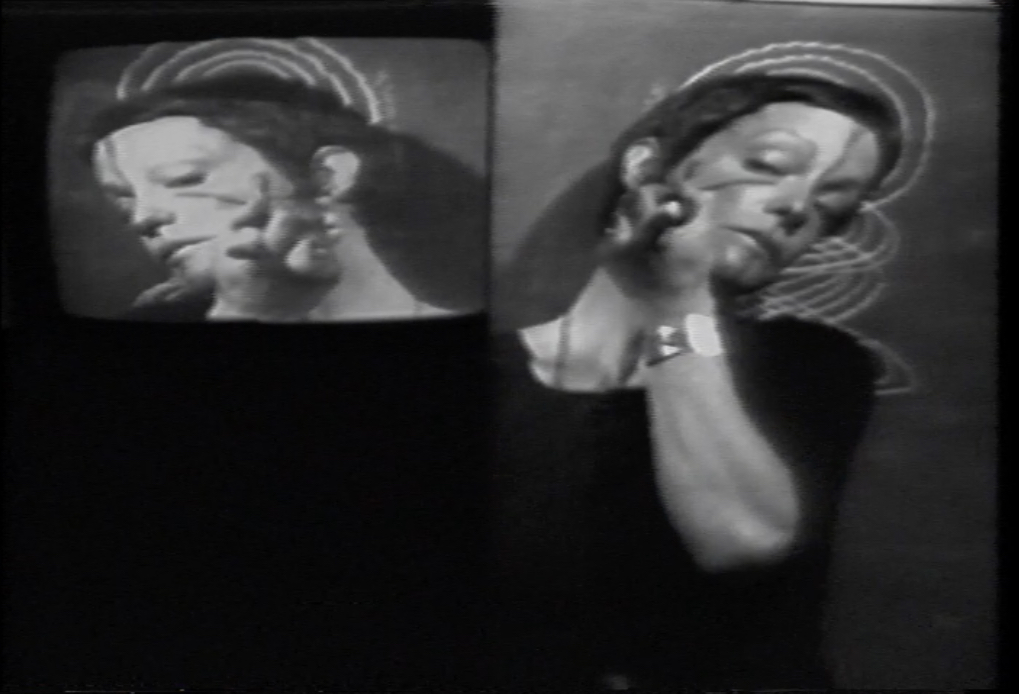

Joan Jonas, Left Side Right Side, 1972. Video still. Black and white single-channel video with sound, 8:50 min. © 2021 Joan Jonas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist.

Every day, I come face to face with myself—in the waiting room, in the top right corner, in the grid. Other people are there, too, other faces or icons, and I look at them, I really do, but I also, always look back at myself. I look to check that I’m present, that I’m listening, that my face is doing what I want it to do. This past year I have watched myself cry, laugh, squirm, pout, think, drift… all manner of performative acts on a sliding scale between “artificial” and “authentic,” sometimes in mirror image, sometimes disconcertingly flipped. From watching myself watch myself, I’ve come to know my face intimately. I’ve also developed a deep distrust of my face. If facetime has taught me anything, it’s that I really don’t know my face at all.

The fraught relationship between video and selfhood was anticipated and interrogated by many female artists in the 1960s and ’70s who used video technology to examine, interrupt, and edit identity. In a 2015 monograph on her work, Joan Jonas explains that she turned to video after hearing of “someone watching Marilyn Monroe as she was sitting in front of a camera being filmed, about the discrepancy between this image and what the camera saw. [Jonas] thought about showing this to an audience.” And she did. In Left Side Right Side (1972), Jonas stands before a mirror, a video camera, and a monitor, with a blackboard behind her. The camera feeds into the monitor, so Jonas can see herself in both monitor and mirror. Early in the short video, we see these two images of Jonas juxtaposed; on the left is her face in the monitor, on the right her face in the mirror. She points to her right eye and announces, “This is my right eye.” She points to her left eye: “This is my left eye.” But given that we are presented with this action in both mirror and monitor, we ask, Is that really her left eye? No, it’s her right. No, it’s both sides—the “real” and the “representation,” the recording and the transmission at once.

The critic Rosalind Krauss, in her paradigmatic 1976 essay “Video: The Aesthetics of Narcissism,” maintained that “self-encapsulation—the body or psyche as its own surround—is everywhere to be found in the corpus of video art.” Krauss’s polemic charged that video is inherently narcissistic, pathologically lacking reflexiveness, perpetually stuck in a collapsed present. Long the definitive text on video art, its authority wavers in the digital economy. As Isobel Harbison persuasively argues in Performing Image, Krauss’s position “becomes untenable in a social sphere where one’s online identity is a constant mode of performance, where an online persona is the necessary extension of an unfixed self.” Preempting the potentiality for video to foster narcissism, Jonas’s video corpus is, in fact, far from solipsistic; rather, she escapes entrapment in the feedback loop through constructing glitches—distortions, disorientations, and fragmentations of her body—that break down the one-to-one fixity of self and its representation. Using the tools of representation to create plural selves, Jonas’s exercises in productive estrangement embrace, even wield, the crisis of representation so aggravated by unrelenting videocalls.

Joan Jonas, Left Side Right Side, 1972. Video still. Black and white single-channel video with sound, 8:50 min. © 2021 Joan Jonas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist.

Jonas performed Left Side Right Side without an audience, alone with her image(s), much like when we preview ourselves waiting for others to join the video conference. Exposing, indeed, foregrounding mediation via monitor and mirror, Jonas addresses the mechanics of the (Arendtian) space of appearance. As Judith Butler notes in Giving an Account of Oneself, “There is already not only an epistemological frame within which the face appears, but an operation of power as well. … After all, under what conditions do some individuals acquire a face, a legible and visible face, and others do not?” Indeed, a 2018 study of three commercial facial recognition systems found their algorithmic programming (and subsequent usage) to produce inherently racist and sexist data, with a 34.7% error rate for women of color compared to an 0.8% error rate for white males. Jonas, a white female subject, would likely register as an individual according to such technology design. However, in one scene, Jonas disrupts the legibility of her face by drawing on it with black pen, circling areas of the face much like a plastic surgeon might. Her face becomes a palimpsest of lines and circles, inscribed, erased, reinscribed, re-erased. By staging estrangement from her image, Jonas confuses the expectation to present a face that indexes a self of a certain gender, race, or sexuality, and instead reprograms the technology to accommodate a self-in-process.

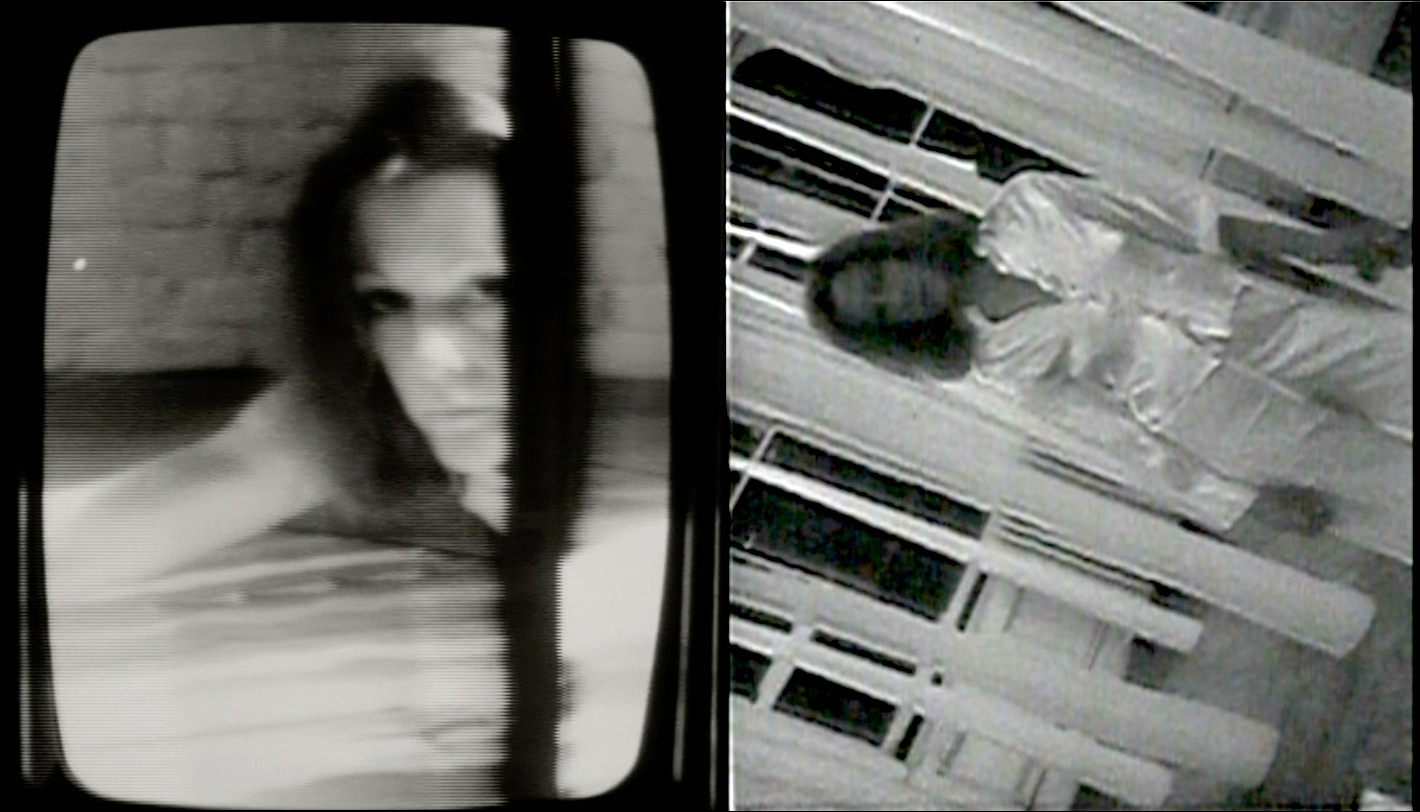

Jonas’s renegotiation of recognition is also explicit in Good Night Good Morning (1976). This video work follows Jonas over an extended period of time as she repeatedly turns on a static video camera, greets it (“good morning” or “goodnight,” alternately), and then turns it off. With a total of fifty-two greetings, the diaristic film charts Jonas as her location, appearance, and temperament change day to day, morning to night, thereby refuting externally imposed identifiers of essentialized femininity (think Marilyn Monroe’s trademark red lips, beauty spot, and effortful blonde coiffure) that hold women’s appearance to an artificial, timeless standard. Elsewhere, in Organic Honey’s Visual Telepathy (1972), Jonas plays up “feminine” signifiers. “Exploring the possibilities of female imagery,” she told Douglas Crimp, “thinking always of a magic show, I attempted to fashion a dialogue between my different disguises and the fantasies they suggested. I always kept my eye on the small monitor in the performance area in order to control the image making.” Such control over representation is evident in Good Night: in one scene, Jonas’s eyes dart beyond the frame to the monitor. She readjusts her position before greeting the camera. Jonas is not simply her image; she is an image maker.

Joan Jonas, Good Night Good Morning, 1976. Video stills. Black and white single-channel video with sound, 11:38 min. © 2021 Joan Jonas / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of the artist.

A normative theory of recognition assumes a subject comes to know oneself as a self through another’s feedback. But, participating in an online economy, the dyadic construction of self and other must be probed and expanded. “It becomes difficult to discern,” Harbison maintains, “whether [new media prosumers] are conversing with people through images or whether [they] are having encounters as images, differently dimensioned versions of [themselves] interacting with others’ different dimensions.” The other is not a separate singularity but can be found within, empathically anticipated and projected by the self. Note that this “self” is not the self-contained, self-defining “I” of Western Enlightenment philosophy, but rather, as Butler posited, “I speak as an ‘I,’ but do not make the mistake of thinking that I know precisely all that I am doing when I speak in that way. I find that my very formation implicates the Other in me, that my own foreignness to myself is, paradoxically, the source of my ethical connection with others.” Butler’s observation takes Jonas’s practice to its next logical step: by incorporating otherness into her selfhood, Jonas strengthens her ethical connection with others. This shift in definition of “self” thus leads toward greater empathy, an opportunity not for narcissism but for outward connection.

But let’s get back to me again! That my gaze drifts back to my own image needn’t provoke as cynical a prognosis as Krauss’s narcissism. It remains a psychological situation, but one that evidences the convergence of what Harbison calls “a will to see, to be seen and change how one is seen.” The conflation of production and reception in instant video feedback might offer a critical opportunity to assess and alter how we are seen by others and by ourselves, but may also, depending on use, reinforce the insidious repression of systems of appearance and recognition. With my Wi-Fi connection and my whiteness, I am accepted into the privileged “we,” but who registers as “who” rather than “what”? “Who” can not only be seen but also heard? The neoliberal terms and conditions of representation serve to reinforce the modern ego as a self-determined subject. But might our networked present offer the opportunity to destabilize and reperform those terms, to understand “I” as multiple, relational, plural… both sides, now? x

Isabelle Bucklow is a writer and researcher interested in film, performance, and narrative. She is an affiliate of UCL Multimedia Anthropology Lab and works for the publishing house Atelier Éditions. Isabelle is based in London.