Artist Matt Keegan’s new book 1996 is an idiosyncratic close study of one pivotal year in politics, activism, and art. Edited by Svetlana Kitto and co-published by Inventory Press and New York Consolidated, 1996 explores artistic formation in the context of the Democratic Party’s slide to the right in the 1990s. The book brings together interviews with two generations of artists—those who completed their undergraduate studies and voted for Bill Clinton in 1996, such as Chitra Ganesh, Elisabeth Subrin, and Seth Price, and those who were born in 1996 and were first eligible to vote in a presidential election in 2016, including Astrid Terrazas and Meetka Otto. Essays by writers such as Mychal Denzel Smith and Natasha Stagg, and archival images from zines, magazines, and newspapers (a Sassy profile of 15-year-old model Ivanka Trump is particularly remarkable), provide further background. 1996 is a yearbook, a time capsule, a queer history, and a treasure trove. Megan Milks spoke with Keegan over video chat days before the wrap of 2020, another astonishing year.

Matt Keegan, 1996 (Los Angeles: Inventory Press, 2020), 12–13. Time magazine covers from 1996. Courtesy of the artist and Inventory Press.

MEGAN MILKS: So often, histories are organized according to decades, periods, waves, or presidencies. Why did you choose 1996?

MATT KEEGAN: In the leadup to the presidential election of 2016, Hillary Clinton’s platform, especially in comparison to Bernie Sanders’s campaign, was akin to that of a centrist Republican, and I wanted to better understand when the Democratic Party began to move to the right. That research led me to read about the formation of the Democratic Leadership Council and the election of Bill Clinton. I chose 1996, the year of Clinton’s reelection, over 1992 because the more research I did, the more significant 1996 became. In the ongoing AIDS crisis, 1996 is considered a watershed moment when people with access to healthcare could receive protease inhibitors that made an HIV+ diagnosis no longer a death sentence. It’s the year when the general public understood the internet, even though in oversimplified and naive terms, since Microsoft launched Internet Explorer in 1995. Fox News started in 1996. Benjamin Netanyahu was first elected as Prime Minister of Israel. Legislation-wise, the Welfare Reform Act, the Telecommunications Act, and the Immigration Reform Act—all of which have great relevance to the current sociopolitical moment—were all signed that year.

MM: This remarkably dense and generous book brings together archival material, oral histories, researched essays, and a play excerpt. Obviously, you had to be shrewd in your selections.

MK: It was a slow build. In 2008, for my book AMERICAMERICA, I interviewed artists who graduated from the School of Visual Arts in 1986. For 1996, I knew from the outset that I wanted to look outside of New York. Los Angeles became a central location, as half of the artists attended the University of California Los Angeles at that time. I then worked with Svetlana Kitto to create the choral form that stitches the separate conversations together into one central discussion, which we titled “An Aroma of ’90s Gay Smells.” From there, I started building the broader puzzle and finding contributors to address what I deemed to be the core topics. I worked to create a balance between commissioned essays by journalists and writers, first-person narratives, and interviews to give a reader a diverse and immersive portrait of the time. The point was never to be exhaustive.

Matt Keegan, 1996 (Los Angeles: Inventory Press, 2020). Courtesy of the artist and Inventory Press.

MM: The archival images peppered through the book—are these from your personal collection?

MK: Over the last three years, I started purchasing magazines from 1996 off eBay—Time, Rolling Stone, Sassy, Us Weekly—and looking for ads and stories that had a resonance with 2020. I also started saving clippings from the New York Times that had a relationship with the midnineties. There are so many gems that didn’t make the cut.

MM: Do you have any favorites?

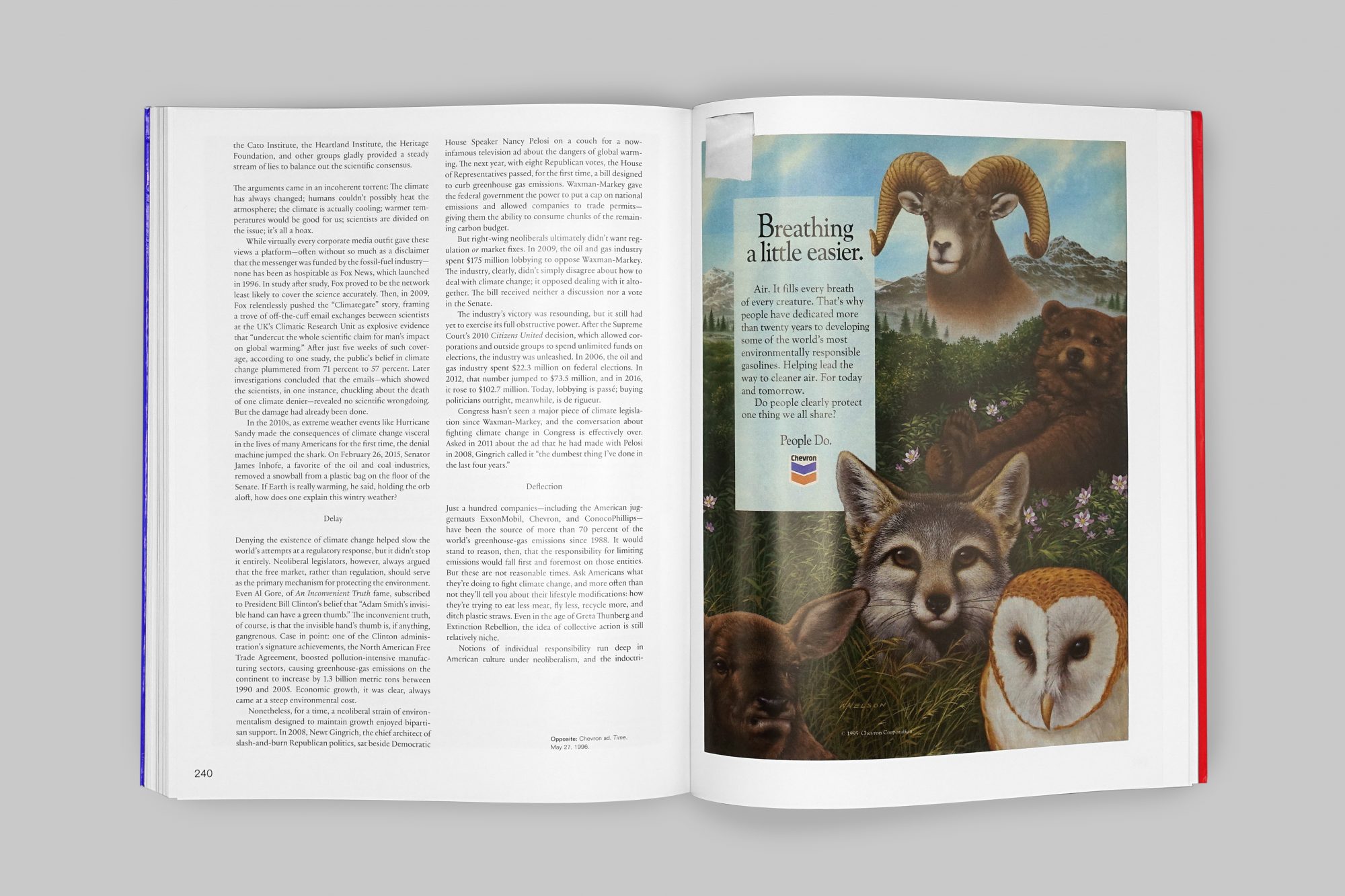

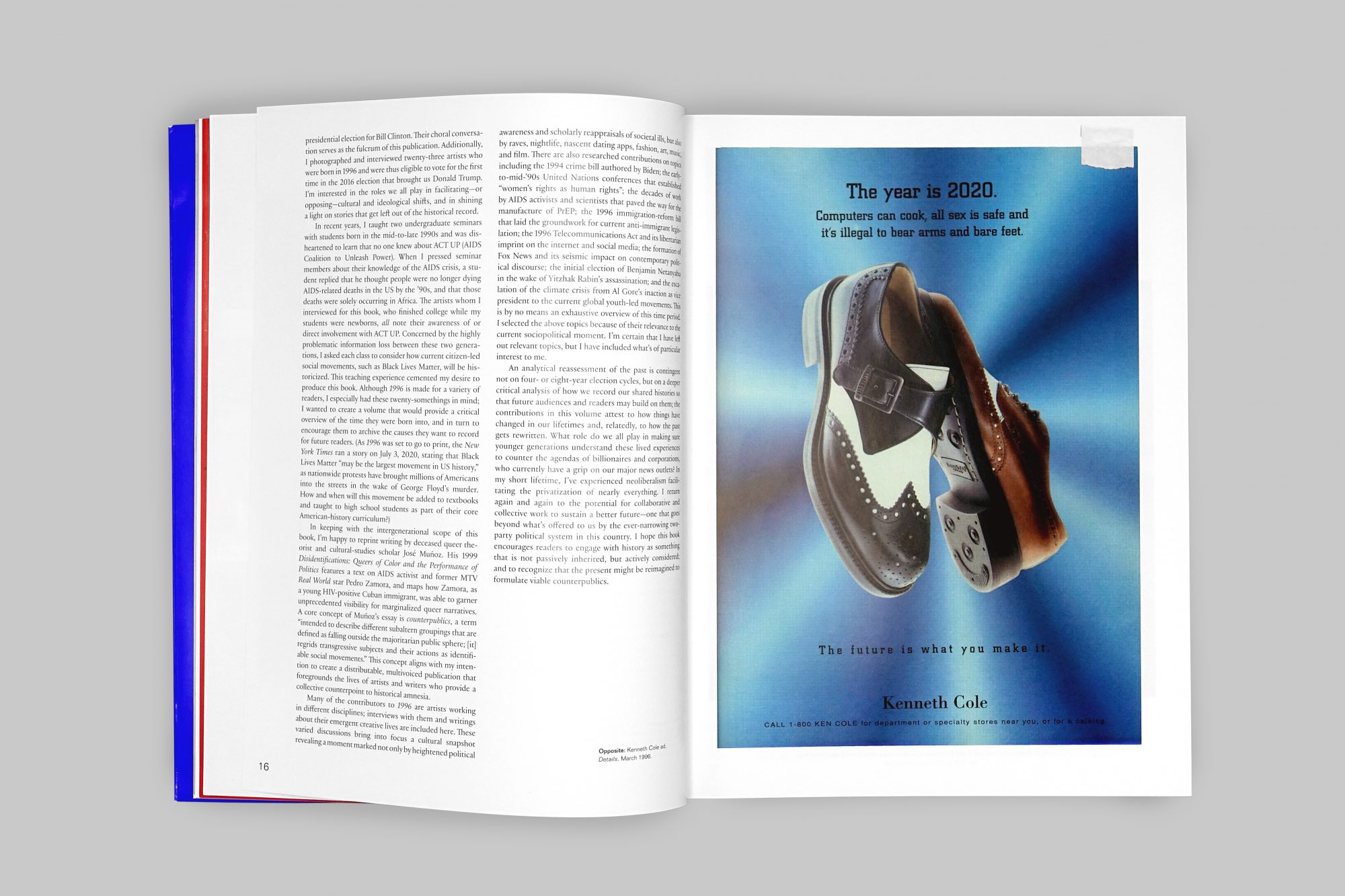

MK: There are so many that are just bonkers. The things that we were sold about the environment—like plastic. The plastic ad is kind of sinister, promoting plastics as “the sixth basic food group.” Or the illustration of sweet animals congregating for a Chevron advertisement, viewed with the knowledge that Big Oil knew about global warming as early as the 1970s but didn’t do anything. There are certain things that age to an ouch, and other things that have aged to a laugh. The Kenneth Cole ad, which reads, “The year is 2020. Computers can cook, all sex is safe and it’s illegal to bear arms and bare feet…” was obviously perfectly timed for my use. I found the ads about the internet to be so naive—like the internet as being a quirky, niche thing rather than the ubiquity that we negotiate every single day of our lives. The idea that the internet could be tailored to you as an alternative, funky person is so quaint and funny.

Matt Keegan, 1996 (Los Angeles: Inventory Press, 2020), 241. Chevron advertisement from Time, May 27, 1996. Courtesy of the artist and Inventory Press.

Matt Keegan, 1996 (Los Angeles: Inventory Press, 2020), 17. Kenneth Cole advertisement from Details, March 1996. Courtesy of the artist and Inventory Press.

MM: One thing I noticed you left out, in terms of key 1996 moments, was the release of Tori Amos’s Boys for Pele.

MK: [Laughs.] I also could have gone into a Mariah Carey spiral. Music is definitely discussed in detail throughout the choral conversation and the interview between Alissa Bennett and Mel Ottenberg, but it’s a topic I could have given more focused attention to. I was listening to so much music at that time.

MM: Who were you in 1996?

MK: I was a sophomore in college. That’s also the year that I came out. Bill Clinton was the first president that I voted for when I was of voting age, in 1996. I thought about my own relationship to that year in regard to voting for Clinton and understanding, even at that time, that I was the target for his candidacy. His playing the saxophone on The Arsenio Hall Show—he was being imaged as a “cool” candidate. I understood that as being differentiated for me as a young consumer and voter versus… the absolute opposite of cool, which would be Bob Dole, his Republican opponent. Or the Independent candidate, Ross Perot, for that matter.

MM: With this book, you’re interested in how artists participate in a broader cultural history. You don’t seem as interested in historicizing the art world as an institution. What was your relationship to art at that time?

MK: Around 1996, I was introduced to Group Material and Fred Wilson’s exhibition Mining the Museum at the Maryland Historical Society in Baltimore, and I was deeply impacted by the possibilities of collaboration and collective work and institutional critique. Sophomore year was the first time I collaborated with a classmate. I did a project with my friend Denise Delgado where we got a grant from our school, Carnegie Mellon, to make an exhibition called The Whole Art Show. We put out a call to people within the city of Pittsburgh via ads on buses and in local newspapers, asking for residents to reach out to us if they considered themselves to be artists. We connected with visual artists, as well as people doing hair, working in textiles, bakers, and musicians. That was an important project for me. It ignited my interest in collaboration, but also this idea of storytelling, too—through public exchange. As a side note, Fred Wilson lectured at Carnegie Mellon the day before The Whole Art Show opened, and Denise and I nervously invited him to the opening and gave him my landline number to contact us. When we came back to my apartment, Fred had left a message and, although he was unable to attend the opening, we screamed as if a rock star had left a message on my answering machine. Total nerds!

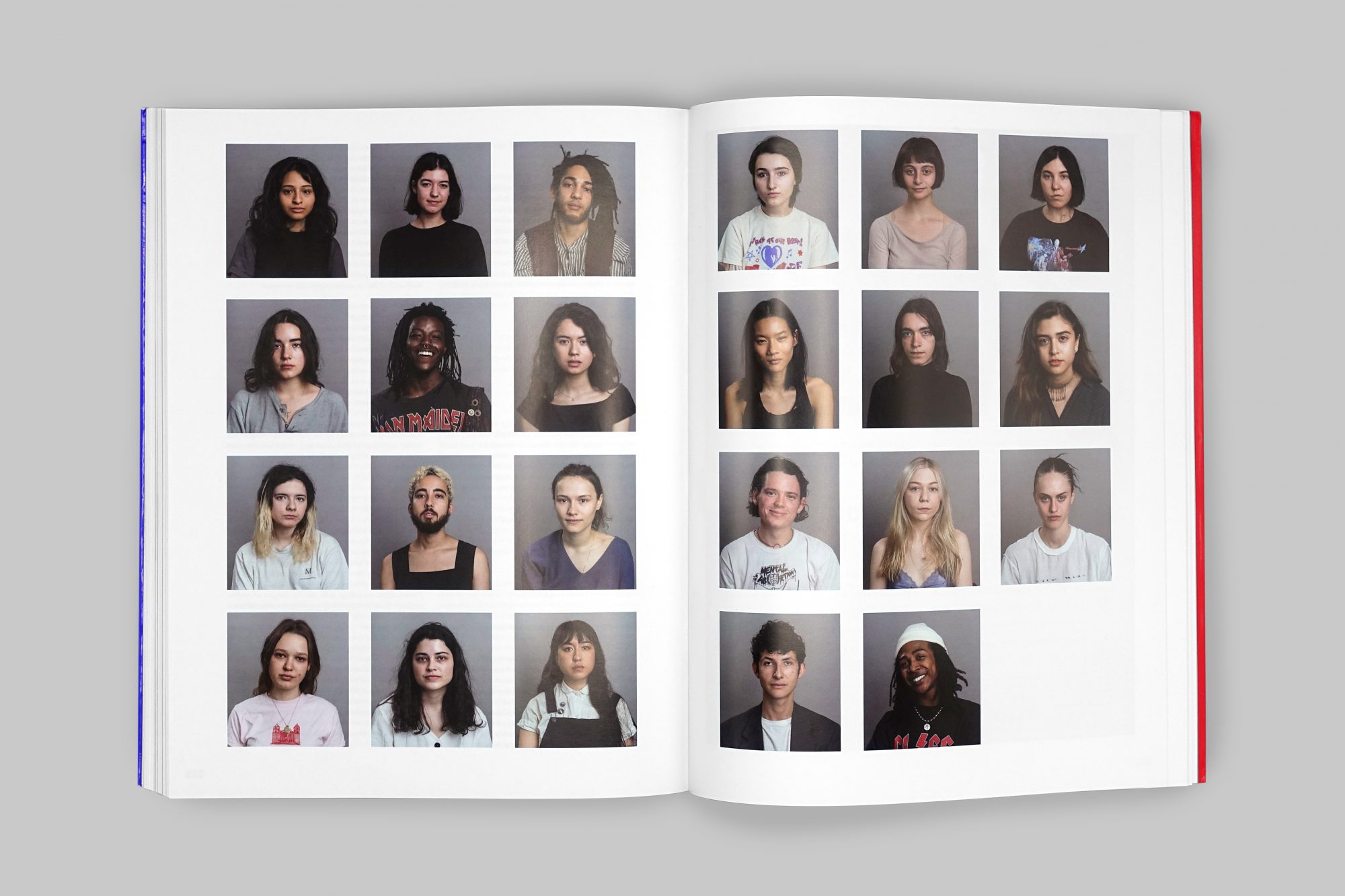

Matt Keegan, 1996 (Los Angeles: Inventory Press, 2020), 236–37. Twenty-three people born in 1996. Courtesy of the artist and Inventory Press. Photos: Adam Pape.

MM: You mention the problem of intergenerational loss, and you present this book as a kind of gift or time capsule for younger generations. I’m curious about your own relationship to intergenerational loss as a queer artist.

MK: Intergenerational loss is a hard thing to articulate. My whole sexual life was defined by AIDS. I never understood sex without illness and death being interwoven. And a lot of queer people around my age understand the tremendous loss of the generation before ours. What immediately comes to mind is a kind of absence that is ill-defined, a mourning of specific people but also a mourning of a past that I only understand through oral history.

I recount in my introduction being shocked that smart and savvy students that I taught in recent years did not know about ACT UP. I was quite upset, and I said to my students, “I want you to understand that this kind of cultural erasure is a conservative project, that this isn’t a fluke that you don’t know this information. This is part of learning—paying attention to what is historicized and what is not. And deciding what role we want to play in countering that erasure.” X

Matt Keegan is an artist based in Brooklyn, New York. He’s a Senior Critic in the Painting and Printmaking Department at Yale University.

Megan Milks is the author of Remember the Internet: Tori Amos Bootleg Webring, forthcoming from Instar Books.