Mark Dion’s first solo exhibition in Los Angeles, Theater of Extinction, on view at Tanya Bonakdar Gallery from April 9–May 25, 2022, foregrounded a conceptual dimension previously overshadowed by the political and ecological narratives of his work. At the center of the installation, a wooden display case presented painted wooden effigies of both real and debunked victims of species extinction, fancifully sized, including a miniature mastodon, the full-sized skulls of a dodo bird and a dire wolf, and models of a “brontosaurus” (an outdated term for a fossil now reclassified as an Apatosaurus) and a “rhinoceros” based on Albrecht Dürer’s 1515 woodcut of a creature he had never seen. Throughout the exhibition, Dion’s use of scale, proportion, and language furthers the sense that the natural world can be understood and affected only through a human lens. For the QxA column, Mark Dion spoke with X-TRA editorial board member Anuradha Vikram about his Bonakdar exhibition and his developing collaboration with the La Brea Tar Pits for Pacific Standard Time 2024: Art x Science x LA.

Mark Dion at La Brea Tar Pits. Courtesy of La Brea Tar Pits.

ANURADHA VIKRAM: In your work, you’ve always been concerned with the natural world and how we humans relate to it. Do you ever make art for animals?

MARK DION: It’s not a goal, but my work does very well with children and dogs. The dogs like the smells and the kids relate to the childlike sense of wonder. We are animals as well, and animals share the senses we have. Many animals are visually oriented. People remark on a dog’s sense of smell being extraordinary. Our sense of smell is extraordinary too.

AV: What themes are you exploring in your research for Pacific Standard Time, for which you are embedded at the La Brea Tar Pits and Museum? What is your role on the master planning team to redesign the site with Weiss/Manfredi Architects?

MD: I’ve never been to LA without going to the tar pits. One thing I really love about PST is that they don’t want you to think about results. This is about taking a vacation from your own methodology and learning from someone else. My role in the team redesigning the tar pits and the George C. Page Museum is to say, let’s just save all the stuff that’s great about this. It has some of the best exhibits in the history of natural history museums. It was the first museum to open its back room to the public, in 1977. That’s a major contribution to the history of museum display.

Mark Dion, Cabinet of Marine Debris – East Coast/West Coast, 2022. Cabinet (wood, glass, metal, paint), glass vases, found marine debris, 104 x 49 x 24 ½ in. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

Mark Dion, Cabinet of Extinction, 2022. Wood, paint, resin sculptures, string, 90 x 113 ½ x 18 in. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

Really what the La Brea Tar Pits have to teach us is encoded in small things. Plants, seeds, tell us what a place was like 30,000 years ago, as much as the short-faced bears. My role is not to replace anything that the museum and archaeologists are already doing, but to add to some of their concerns. How do we shift our interest from the big things to the small things, the pollen and the seeds and the small mammals, the packrat instead of the mastodon? Not everything that lived at the Tar Pits is gone. The coyote is still pretty interesting—it’s not a dire wolf, but the coyote has a story of survival whereas the dire wolf went extinct.

Display of dire wolf skulls at the Page Museum. Courtesy of La Brea Tar Pits.

AV: How do the works on view at Tanya Bonakdar, specifically the works with animals and tar, relate to your earlier works such as The Tar Museum (2006)?

MD: The Tar Museum used tar in a similar way to The Anatomy of Melancholy – Dodo (2021) and Tar and Feathers – Flamingo (2019), but in the newer works there are the trinkets of the recent past—costume jewelry and keys and dice and dominos and game pieces and junk-drawer objects, detritus of our consumer society. The work ping-pongs between critiquing the culture of collecting and celebrating it. The relationship to collecting is complex and somewhat ambivalent. The most important thing is that we are at an ecological turning point. If we get it right, we get to keep the planet, and if we get it wrong, we’re going to have unprecedented disaster.

When I go through the museum, and go through contemporary exhibitions, I don’t see anything like that represented. When you look at a European art museum and you look at what artists were doing during World War II, a lot of artists didn’t have anything to say about that historical moment. I would want to look back at the turn of the present century and see that there are some artists who actually recognized this moment, artists like Walton Ford, Richard Misrach, Kiki Smith, and Alexis Rockman. That’s how I imagine my work functioning, as a thoughtful attempt to understand our moment, to trace the history of ideas that have brought us to our suicidal relationship to the natural world.

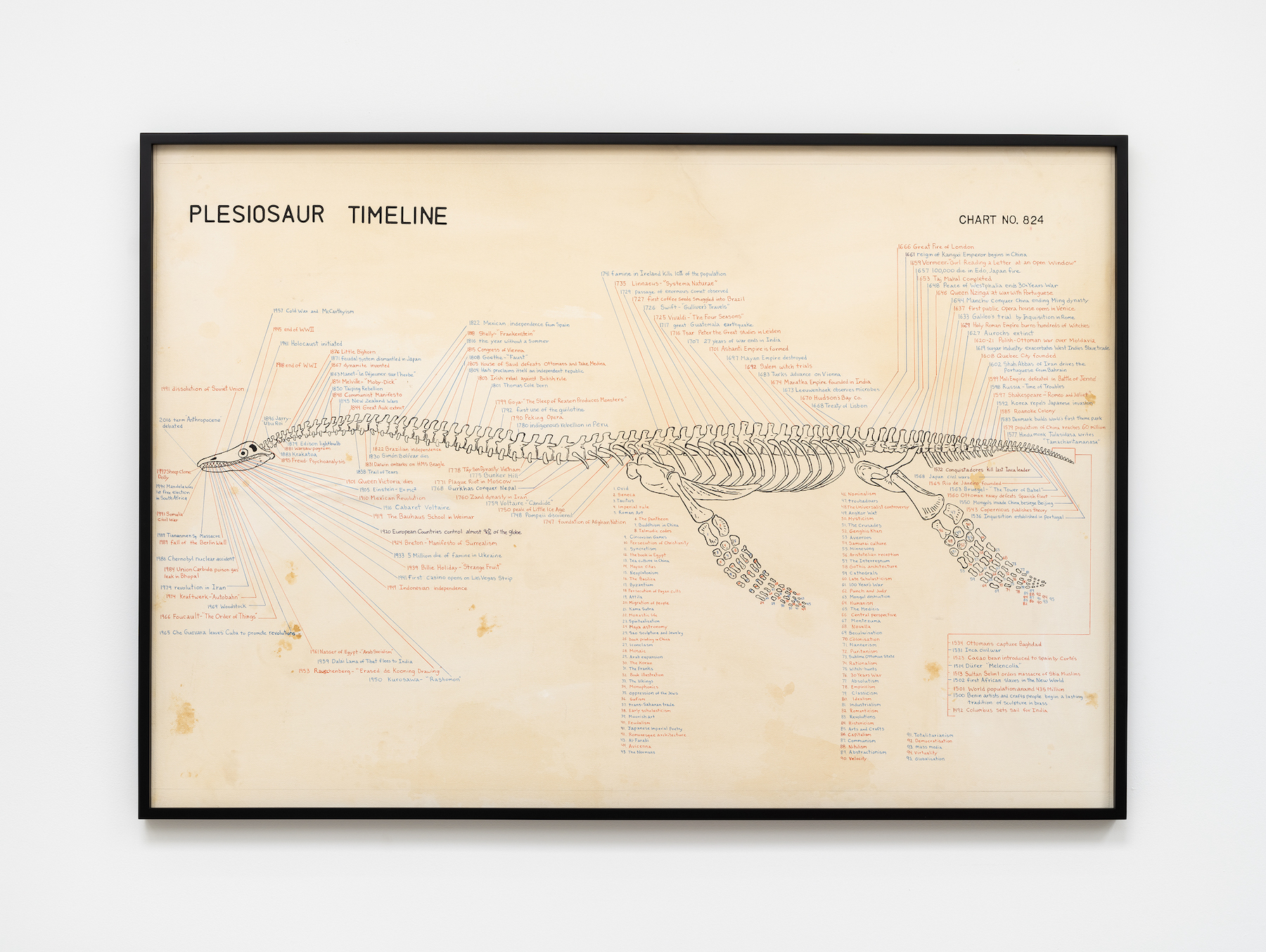

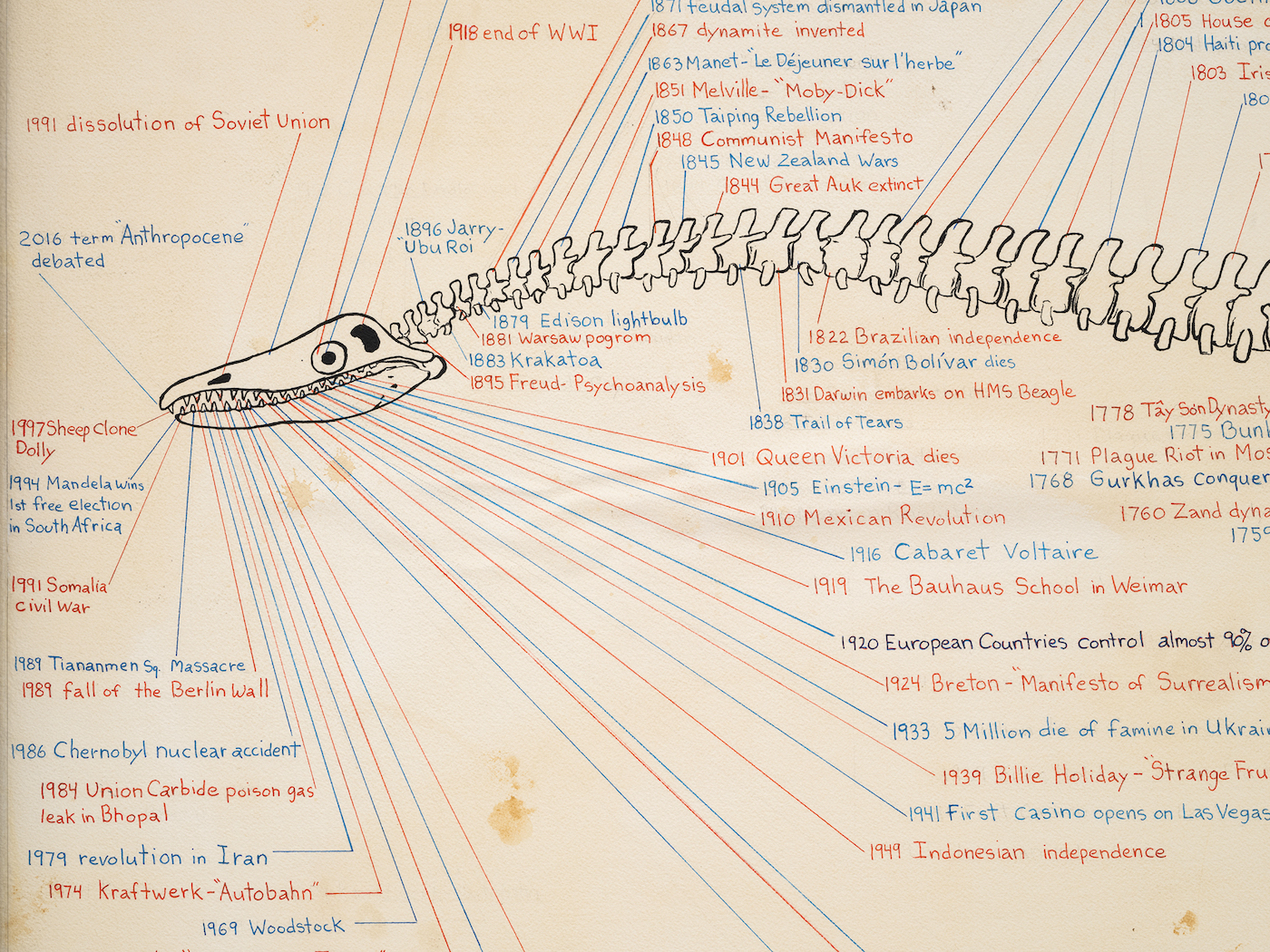

Mark Dion, Plesiosaur Timeline, 2020. Ink on stained paper. 44 ¾ x 64 ½ x 1 ½ in. (framed). Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

Mark Dion, Plesiosaur Timeline, 2020. Detail. Ink on stained paper. 44 ¾ x 64 ½ x 1 ½ in. (framed). Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

AV: How do you understand works like Cabinet of Marine Debris – East Coast/West Coast (2022) or the earlier drawing Gyre (2013), which present our plastic trash as organized archives of human activity? Does this reflect a larger shift in archaeology from looking at objects of importance to looking at everyday items?

MD: I’m more interested in doing a dig in the privy than I am in doing a dig in the President’s garbage. That’s borne out in these pieces because they are collections of everyday discards. This is akin to the new archaeology that digs into the servants’ quarters rather than the lives of the rich and famous.

AV: You were trained by language-oriented Conceptualists and you emphasize the object. However, there’s a lot of language in your show at Bonakdar, especially in the drawings.

Mark Dion, Tar and Feathers – Flamingo, 2019. Flamingo sculpture, tar, small precious objects, trash can, crate, 75 x 30 x 25 in. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

Mark Dion, Tar and Feathers – Flamingo, 2019. Detail. Flamingo sculpture, tar, small precious objects, trash can, crate, 75 x 30 x 25 in. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Ruben Diaz.

Excavation at Project 23. Courtesy of La Brea Tar Pits.

MD: The drawings are intentionally mischievous. The legacy of those drawings starts with the 1925 Surrealist map of the world, the comics of Ad Reinhardt, moves through the hijacking of graphics by the Situationist International and later by punk. These drawings play with infographics within that lineage. By twisting information, I don’t think I’m doing disinformation, but I’m training people to be distrustful. The viewer has to stay on their toes from one object to the next.

AV: Are you critical of science as an exclusive knowledge practice?

MD: Science can be exclusive to non-specialists. Science is a set of rules, and once you transgress those rules, you’re no longer doing science. But, with no elasticity, what they lose in those rules is a way to describe the world that’s closer to the way we live in it. I learn a lot from thinkers like Timothy Morton, Cary Wolfe, Donna Haraway, and the whole Critical Posthumanist movement. But I want people to have access to this work whether they have a PhD or not. Everyone should find something in this work that engages them, even if they don’t think about it in terms of art. x

Courtesy of La Brea Tar Pits.

Mark Dion is an artist who frequently collaborates with museums of natural history, aquariums, zoos and other institutions mandated to produce public knowledge on the topic of nature. By locating the roots of environmental politics and public policy in the construction of knowledge about nature, Dion questions the objectivity and authoritative role of the scientific voice in contemporary society, tracking how pseudoscience, social agendas, and ideology creep into public discourse and knowledge production.

Anuradha Vikram is a curator and writer based in Los Angeles. They are co-curator of the 2024 Pacific Standard Time exhibition Atmosphere of Sound: Sonic Art in Times of Climate Disruption and a member of X-TRA’s editorial board.