From the dead corners of the internet, the work of the late German-born latter-day surrealist Sibylle Ruppert roars to life. There are machines and instruments in her abattoirial pictures, sure, but as Sierra Komar writes for the Lives column, there is much more flesh.

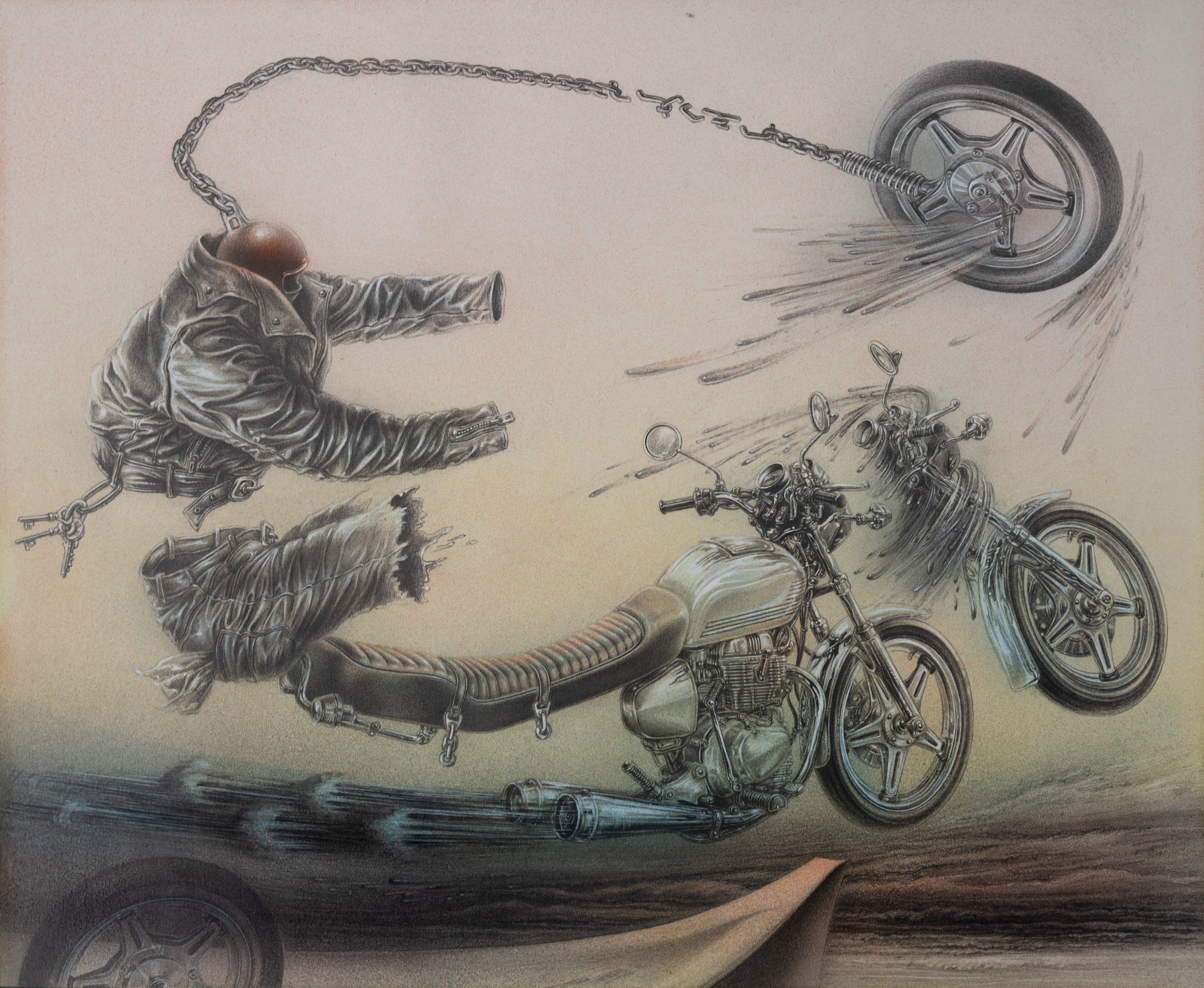

Sibylle Ruppert. Hit something, 1977. Colored pencil on paper, 14 x 12 in. Courtesy of the artist and Blue Velvet, Zurich.

I first encountered the work of Sibylle Ruppert by mistake, drifting down a Google Images rabbit hole of H.R. Giger’s Biomechanical Landscapes. Among the Swiss artist’s obsidian terrains, I noticed an outlier: a conspicuous burst of color and figuration in the otherwise metallic expanse. This was Ruppert’s Hit something (1977), a gloriously campy sketch of a hybrid human/motorcycle in the throes of a violent collision. A Futurist fusion of body and machine rendered in the saturated, erotically charged style of 1950s pulp fiction, it depicts the fragments of a bike and a rippling, leather jacket-wearing torso suspended, mid-explosion, against a bright gradient.

Clicking through to the website hosting the image, I suddenly found myself deep in a Web 1.0 ruinscape: an anachronistic but familiar environment of cluttered text, broken links, and meandering guestbook-style comment sections. Such arcane corners of the internet were, save a small number of hard-to-source exhibition catalogues, the only places where one could find any discussion of Ruppert and her pulsing gothic vision (though this has changed in the past year thanks to Zurich-based gallery Blue Velvet Projects, who staged a large exhibition of Ruppert’s work in 2022 and now represent her estate). Created in the decades between 1960 and 1990, this oeuvre is diverse in both scale and medium, encompassing everything from monumental crayon and charcoal quadriptychs to diminutive etchings.

As I ventured further into the labyrinth of forgotten WordPress sites where Ruppert’s creations have been circulated, however, it quickly became clear to me that the sketch that had brought me there was itself somewhat of an outlier. Amid the rest of Ruppert’s pieces—convulsing, chimerical tableaux inspired by the transgressive, sexually explicit writings of the Marquis de Sade, the Comte de Lautréamont, and Georges Bataille—Hit something is ironically gentle. A moment of light-hearted carnage amidst an artistic output defined by significantly greater violence is the equivalent, in Ruppert’s world, of a caress.

Sibylle Ruppert. Le Sacrifice, 1980. Oil and tempera on canvas, 25½ x 32 in. Courtesy of the artist and Blue Velvet, Zurich.

Alternating between drama and sparseness, the few published biographies of Ruppert intensify, rather than lessen, her mystique. Accounts of her early years, in particular, tend to reference a handful of sensational events—a religious experience at age 10, a brief stint living in a castle—that lend her a fabled, almost mythological air. Born in Frankfurt in 1942, Ruppert studied art at the Städelschule but spent most of her young adult life pursuing a dance career. Her father was a graphic designer and painter, and, after leaving the dance world, she taught drawing at the art school that he founded (the Westend Art School, later known as the Academy of Visual Arts, Frankfurt), as well as in hospitals, prisons, and rehabilitation centers. Throughout the 1970s, she was affiliated with both Sydow-Zirkwitz, a little-known gallery in Frankfurt whose idiosyncratic exhibition roster included Ernst Fuchs, mystical founder of the Vienna School of Fantastic Realism; and Bijan Aalam, an equally unsung Parisian gallery that showed the work of H.R. Giger, with whom Ruppert was close. Little is known about her later years, save for the fact that she resided alone in Paris, where she passed away in 2011.

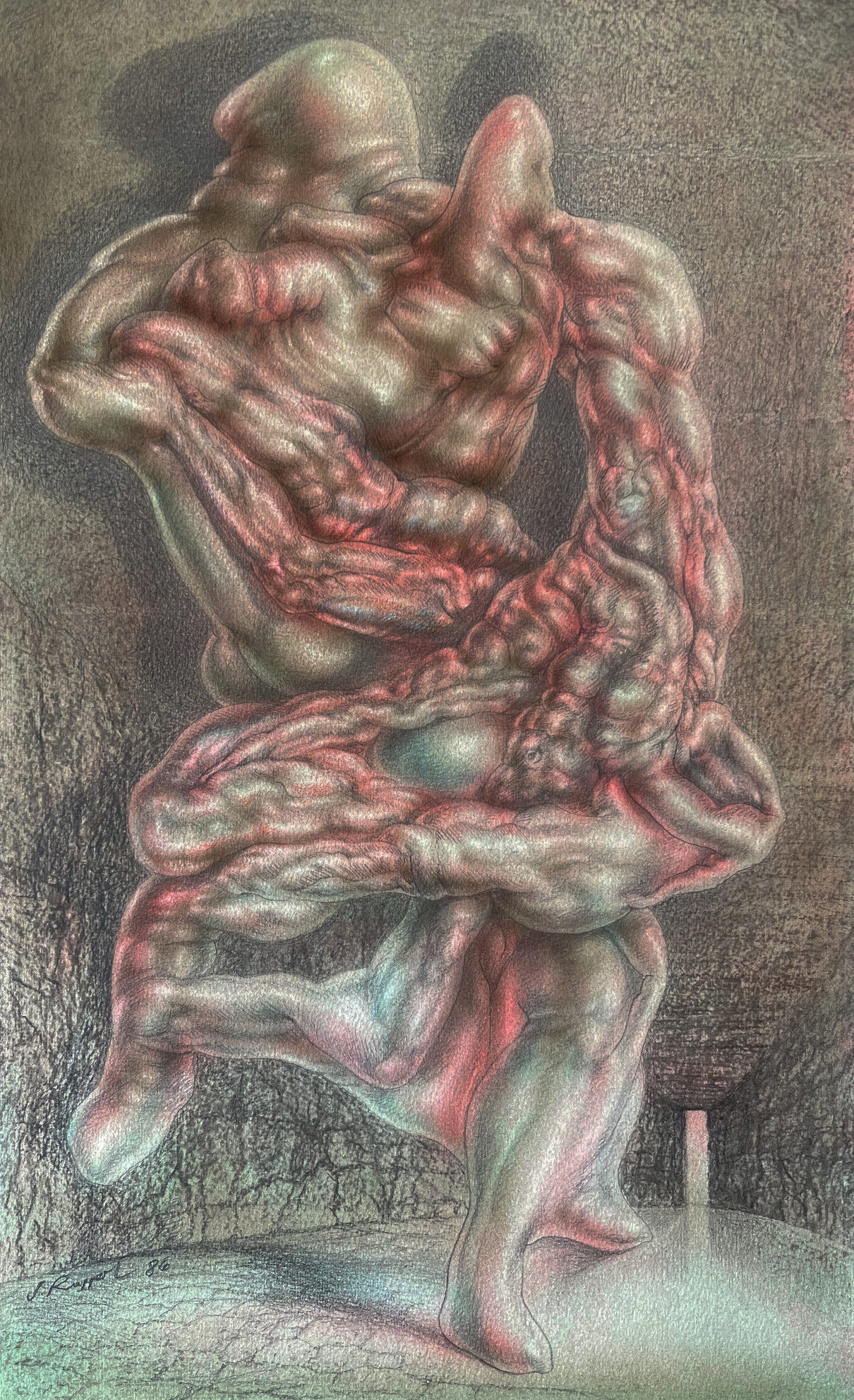

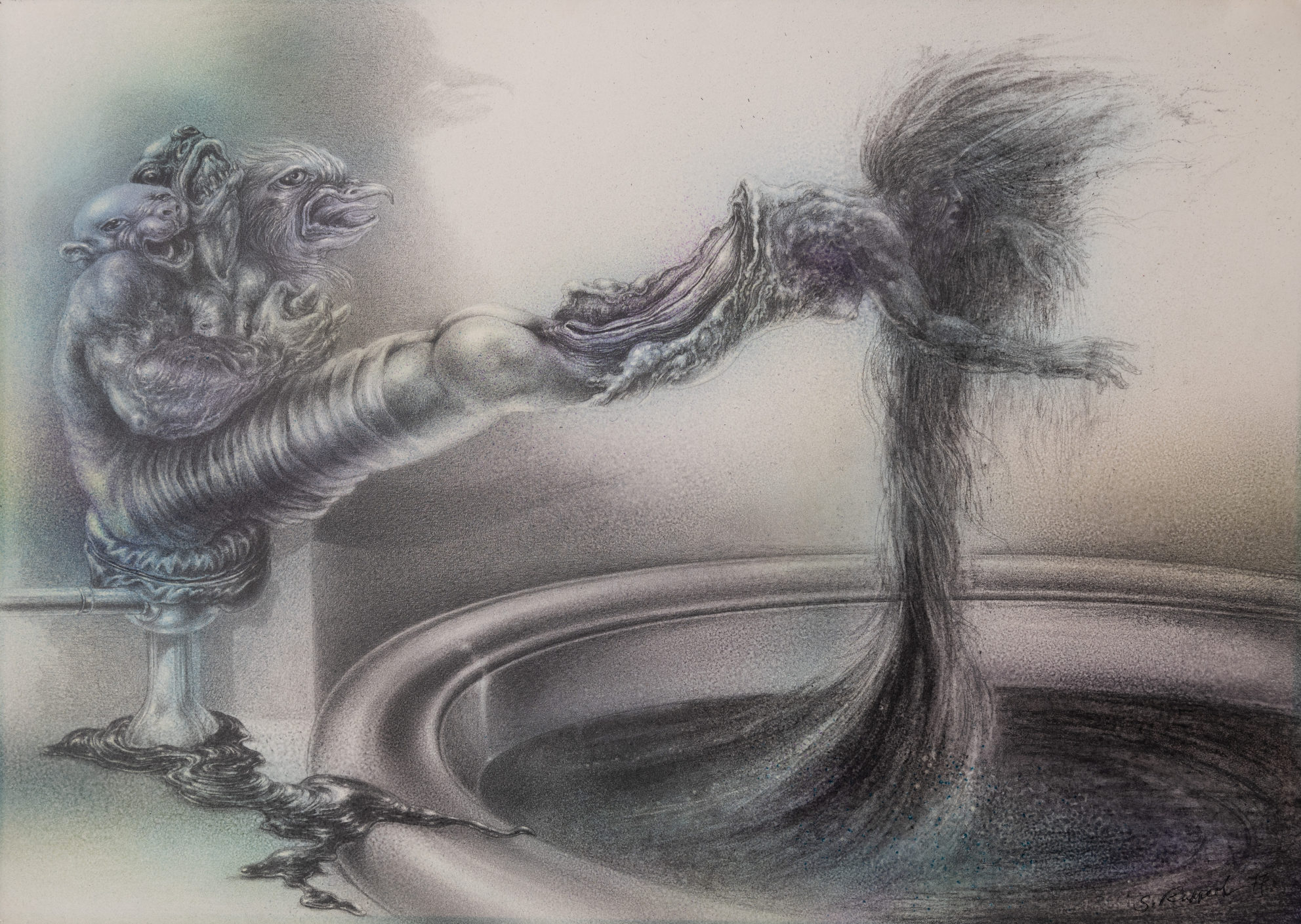

Ruppert’s work, like Giger’s, straddles the boundary between fine art and popular forms of visual culture: a stylistically liminal position that proved difficult to absorb for the more traditional museum and gallery circuit. This, however, is where their similarities end, for while Giger’s world is an osseous one, Ruppert’s sensibility is definitively of the flesh. Muscle, not bone or carapace, fills her works. It is muscle that dominates in Dessin pour D.A.F. de SADE (1976), a charcoal drawing in which two beaked creatures ravage an androgynous, Herculean torso. Aleatory plumes of fabric drift around the margins of this chaotic scene, their undulating folds rendered in a way that mirrors the sculpted, contorting figure at its center. Under Ruppert’s hand, everything is jacked—anabolic to the point of bursting—and even inorganic elements like fabric start to bulge. In Hit something, the exaggerated pleats of the jacket and pants adorning the destroyed torso seem closer to sinew than they are to clothing, as do those of the kinky, PVC-esque suit worn by the acephalic figure in the 1980 oil painting Le Sacrifice. This preoccupation with matters of the flesh seems to have only grown stronger throughout Ruppert’s career, reaching its apotheosis in the small-scale, 1986 crayon drawing Ringkampf, which depicts an amorphous mound of muscle writhing in the center of the page. Void of identifying details, such as any distinguishable limbs or facial features, these entities are flesh in its purest form: featureless piles that read as dual only thanks to the work’s title.

Sibylle Ruppert. Dessin pour D.A.F. de SADE, 1976. Charcoal on paper, 41 x 32¾ in. Courtesy of the artist and Blue Velvet, Zurich.

Sibylle Ruppert. Ringkampf, 1986. Colored pencil and graphite on paper, 13¼ x 8 in.

The setting of Ringkampf is unremarkable: a dark, empty passageway punctuated by the bright rectangle of a far-off door. Such simple, uncrowded backdrops—often little more than the lines required to generate a horizon or establish a sense of interior space—are a hallmark of Ruppert’s compositions, which consistently showcase figure over environment. Ruppert’s figures are colossal, commandeering, extending to the edges of her images. This privileging of the figure, however, does not equate to a celebration of the subject, as the figures in question bear little resemblance to the “autonomous, discrete, and unequivocally sexed” body upon which, Lautréamont scholar Cecile Lindsay has argued, this subject depends.

Most every figure that appears in Ruppert’s work is multiple: an array of incomplete beings, momentarily but precariously fused. Take, for example, the 1976 drawing Qui est tu, a chiaroscuro-style affair which depicts a complex, nearly indescribable amalgam made up of an androgynous muscled torso, a strange beaked creature (itself an unnatural meta-hybrid of a bird and a boot), a simultaneously sculpted and feathery pair of legs, and a grimacing, mask-like face. There are also the warring composites of the 1977 charcoal portrait Empusae Raptus, one of which consists of an anthropomorphic pig merged with the blade of a knife. Phallic forms appear frequently in these amalgams, yet they mix indiscriminately with corporeal signifiers of the feminine, making traditional gender divisions inapplicable. Arachnoid appendages and avian parts—beaks, feathers, talons—are also common; flora and fauna interpenetrate indiscriminately. The animate and inanimate realms are equally represented, making these figures not just androgynous, but distinctly other-than-human.

Sibylle Ruppert. La Fontaine, 1977. Charcoal on paper, 14 x 10¼ in. Courtesy of the artist and Blue Velvet, Zurich.

In many ways, these heterogeneous chimeras recall the famous definition of subject-as-crowd articulated in the opening lines of Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari’s A Thousand Plateaus. The perceptible violence that plagues them, however, suggests Ruppert’s particular vision of self-dissolution borrows more from Bataillean sovereignty than Deleuzian becoming. Though multiple, her hybrids are not subjects in process, but subjects at war: their constituent elements perpetually rip, tear, and violate each other from within. In Le Spectacle de l’Univers (1977), a hypertrophic cyclops uses one of its pairs of arms to squeeze itself with such force that its eye shoots out of its socket, while in Empusae Raptus, a secondary, fanged creature bursts out of a bipedal tower of flesh, lacerating their shared anatomy. Upon closer attention, it is often revealed that there are several episodes of intra-subjective brutality occurring simultaneously within any given assemblage: multiple eruptions of auto-consumption, auto-penetration, and auto-mutilation within in one body. As with a Renaissance relief, one needs time to take in every small, fractal instance of mayhem and depravity in a Ruppert piece.

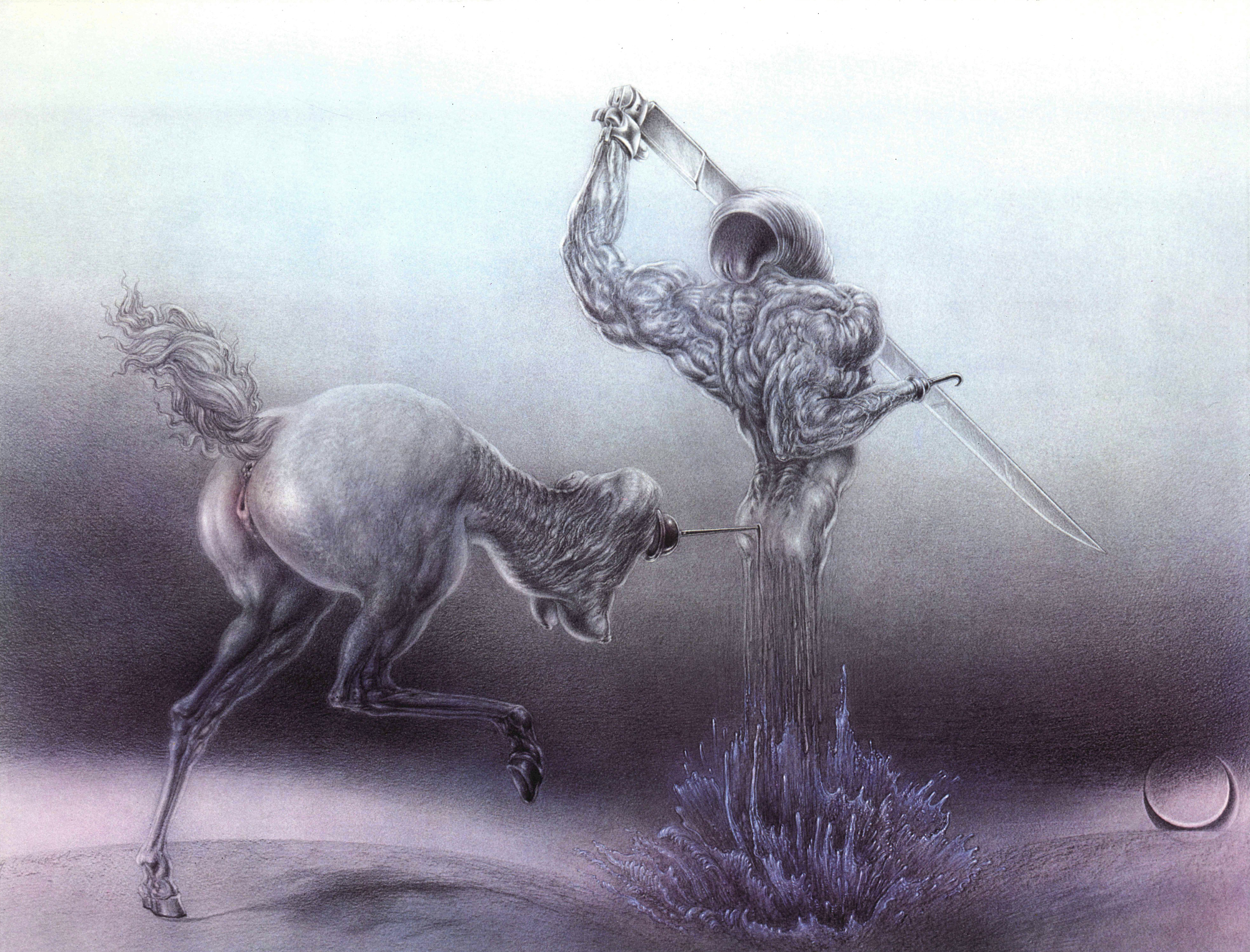

Displaced by multiplicity or torn asunder by one of its constituents, the unitary subject disappears as the figure is brought to the fore. For Bataille, this disavowal of the individual would constitute the true source of Ruppert’s work’s obscenity: “our name,” he writes in Erotism: Death and Sensuality, “for the uneasiness which upsets the physical state associated with self-possession, with the possession of a recognized and stable individuality.” Of course, Ruppert’s oeuvre also brims with conventional sex and gore. Indeed, this is likely why it has languished for so long, a fate which often befalls female artists who engage with such transgressive material. A pair of etchings from the early 1970s dedicated to the Marquis de Sade are pornographic in the most obvious sense, offering zoomed-in, focused views of dripping orifices penetrated by fingers and phallic forms. Thickly inked and contained in dense, compact bursts in the center of the page, they make Hans Bellmer’s better-known works on the same theme, with their delicate lines and ethereal spirals, seem positively demure. Ruppert’s Dessins pour Lautréamont series—a set of illustrations for the Comte de Lautréamont’s twisted, 19th-century prose poem Les Chants de Maldoror—also offers plenty in the way of interpersonal violence, showing figures fighting it out with spears and knives against tranquil, otherworldly backdrops. Throughout, the project of subjective annihilation persists, always rendered with a brutality equal to, if not exceeding, any battle taking place between or within beings.

Sibylle Ruppert, Sub Rosa et Abyssus, 1979. Colored pencil on paper, 18½ x 14 in. Courtesy of the artist and Blue Velvet, Zurich.

Four works from this series—L’Escarpolette (1978), Sub Rosa et Abyssus (1979), Epiphanie et Femme (1979), and La Cage du Temps (1978)—see Ruppert introduce subtle washes of red, pink, and blue to into an otherwise monochrome palette, suffusing everything with a crepuscular, alien iridescence perfectly suited to the extraterrestrial ambiance of Lautréamont’s poem. A similar dark patina often seems to cling to Ruppert and her enigmatic biography, embellished with cinematic scenes. Beneath this hagiographic sheen, however, is a more profound absence: the dearth of any sort of testimony from the artist herself, of any interviews, quotes, or commentary in which she might offer insight into herself or her process. It is perhaps for this reason that, throughout my research, I found myself thinking often of a quote by French writer Julian Torma regarding the notoriously elusive Lautréamont. “[There is] no key,” he observed in Euphorisms, “For Lautréamont is not a door… when the house is blown up, there’s nothing to shut or open.” Beyond capturing Ruppert’s impenetrability as a figure, however, Torma’s metaphor also conveys one of the most crucial characteristics of her work: its insistence on mangling traditional conceptions of subjecthood. In Ruppert’s work, just as in her life, to seek this subject is to find only ruins: or, at best, a few fragments, mid-explosion. x

Sierra Komar is a writer and archivist living in Montréal and Los Angeles.