In 2008, I was invited by Charlie White, then-director of the University of Southern California’s Roski School of Fine Arts, to contribute an essay to the catalog accompanying that year’s MFA graduate exhibition. Considering the etymological link between critique and crisis, the first bearing a diagnostic relation to the second, I hit on the idea that art education could perhaps be considered from a medical perspective, in the specific terms of bacteriology and inoculation. This became the thematic through-line of my essay, which was titled “Critical Times.” Its concluding sentences read: “Knowing that it only survives through regular, immunizing infusions of the poison that would otherwise destroy it, this is what makes art ‘special’ today. The point of critique is not to build a stronger artist or artwork. To the contrary, what one learns as an MFA student is how to live with the disease.”

Initially, this seemed like a novel approach to the subject. However, more recently, while researching the work of Kazimir Malevich for another project, I learned that this medical outlook was in fact one that this artist staunchly upheld in both the studio and the classroom. In the light of this finding, it occurred to me that my original thoughts on the matter could bear some revision. Moreover, in the interim between my earlier text and this one, we have witnessed the astounding corporate takedown of the Roski School of Fine Arts. This event generated a great deal of critical blowback, which was met, at every step of the way, with the upbeat, boosterish claims of a patently mandated institutional consensus. This critical struggle, although it was waged on the front of “Disaster Capitalism,” also paradoxically recalled the situation encountered by Malevich almost a century earlier in Russia, within an educational complex then undergoing Communist restructuring.1

More recently, the Roski school has unveiled a new program that is not entirely unpromising, but the fact remains that this is the product of a brutal “regime change.” The relation of critique to crisis within art school, which I began by observing in the metaphorical light of physiology, always discloses a political cause that can be analyzed somewhat more concretely as a historical inheritance. Accordingly, I would like to take a step back from our immediate problems in art school for the sake of a longer-range vantage. The Roski debate, as it continues, can only grow increasingly one-sided on both sides, and into the chasm that opens between them, much gets lost. Although the collapse of the old regime can be blamed largely on external pressures, one could also argue that a certain measure of crisis is inherent in the very structure of art education, and this too can be subjected to diagnostic critique. What follows is a highly selective historical overview of artist-teachers who confronted this crisis head-on, if sometimes eccentrically. Whatever course of treatment might be derived from their examples will have to remain questionable on the pragmatic plane, but this is not to deny their seriousness—far from it. Let’s begin with Malevich, my case in point.

1

We tend to think of Kazimir Malevich as a serious man. With the appearance of his Black Square (1915), possibly the first “last” painting, he had arrived, in both theory and practice, at the bottom of things. This somber monochrome is a work that reduces the act of painterly composition to the minimum of merely reiterating its framing conditions. The band of white that traces the edges of the central black shape defines that shape, in the artist’s own words, as a “painted mass,” and one that is held securely within painting, within art.2 Black Square was proposed as a demonstration—today we might say a “teachable moment”—and its lesson is this: art cannot be about anything and everything. The artist who takes this lesson to heart will be charged with seeking out content appropriate only to art. In order to do this, Malevich first had to take leave of the world as it is.

Following a preliminary “sketch” that Malevich produced as the set designer for the Cubo-Futurist opera Victory Over the Sun, which premiered in St. Petersburg’s Luna Park theater in 1913, Black Square was officially unveiled two years later at the event 0,10: The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings. “I have transformed myself into a zero of form,” the artist triumphantly announced in a brochure printed to accompany the show, highlighting his achievement in distilling painting down to an essence no longer beholden to perceptual phenomena, the world as appearance.3 His statement resounds with the overblown heroic tone typical of early twentieth-century avant-gardism, and today we might be tempted to greet it with a skeptically arched eyebrow, or even as a cause for mirth. But this is not to suggest that Malevich was oblivious to the potentially off-putting effect of his words. Of particular note is the canny conflation of subject and object positions within his statement: it is not, or not only, the painting that has been set back to zero, but “I,” the painter, as well. In order to arrive at the grounding origin of all that has accumulated upon the painterly surface through history, and to find there the medium’s teleological end-point, “I” too must be nullified.

Zero—what kind of a teacher is this? A philosophical one, I want to suggest, stressing that aspect of philosophy that is devoted to non-applicable, un-pragmatic, anti-positivistic truth. In this regard, teleology, which in Aristotelian terms is defined as “the doctrine of final cause,” becomes salient. From a worldly can-do perspective, the word immediately sounds a note of alarming paradox, forcing all our most advanced pursuits—along with the sum total of our gathered knowledge in science, technology, social engineering, product design, business, culture, pedagogy, self-help, and what have you—to collapse in on themselves. That is, in the end, at the limit of progress, all that we learn is where, how, and why we began. Only in the religious terms of revelation does teleology make sense, and here it makes absolute sense, a sense that applies equally to everyone. In the case of art, a somewhat more limited, and perhaps exclusive, form comes to light. This is the domain of “the weak universalism,” to cite the title of an essay by Boris Groys, who builds on Walter Benjamin’s concept of “weak messianism.” Groys proceeds to propose Malevich as a model, drawing a parallel between his aesthetic lessons and those of Saint Paul in the religious sphere, both of them equally devoted to “the constant revocation of every vocation.”4 The way to Malevich’s “zero” is contra mundum. I refuse, my painting refuses; only by renouncing my expertise as a painter do I come to understand just what it is I should do, what all painters—and by extension, in principle, everyone else—should do. This revelation is attained by working backward and traveling full circle, but without winding us up anywhere near where we began. The end is not the same as the beginning, for now at last you know! Black Square, then, marks a new beginning, and the number 0,10, affixed to the title of The Last Futurist Exhibition of Paintings, in which the work was delivered to public life, indicates the future course to be traveled: beyond zero—or better, beneath it—there is always further to go.

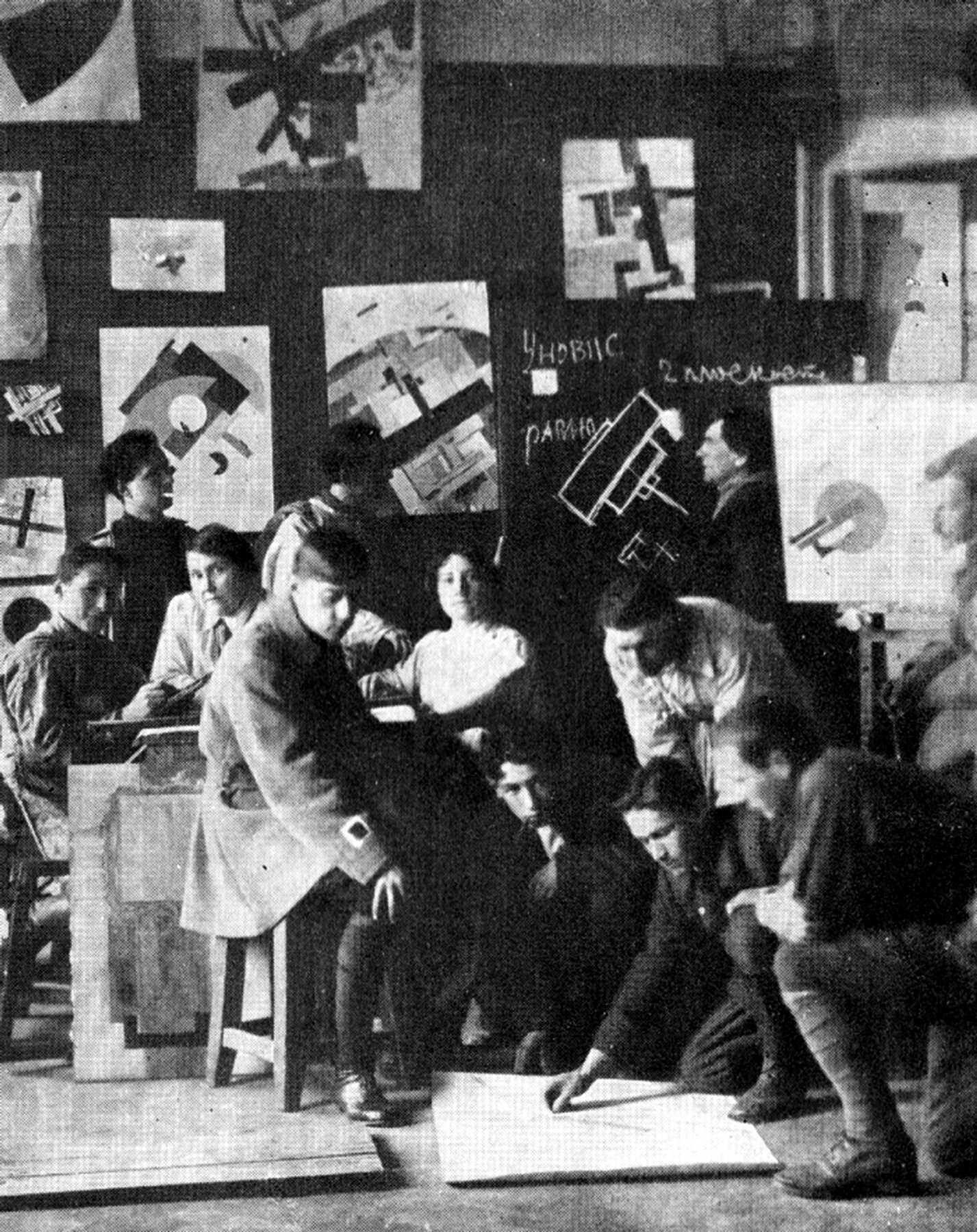

Between the years 1920 and 1927, Malevich largely abstained from any sort of studio production, and this was due to the missionary zeal with which he took up teaching. The gospel of Black Square, once it had been revealed, had to be spread. Malevich’s career as a pedagogue began in September 1917, when the then-provisional Soviet government recalled him from military service to act as deputy director of its newly formed arts section. He immediately set about organizing a countrywide “People’s Academy” art school system. Following the October Revolution in that same year, Malevich taught for a time at the Free State Art Studios in Moscow. In 1919, he departed for the Vitebsk School of Art and there became a highly influential instructor, forming with a devoted group of students the organization UNOVIS (an acronym for The Champions of the New Art), which proceeded to subsume the largest part of the school’s curriculum to their aesthetic ideology, as expounded in the pamphlet “On New Systems in Art.” In 1922, Malevich left Vitebsk, which was then was struggling financially, and with his student followers and several colleagues on staff set off for St. Petersburg. In 1923, he became the director of INKhUK, the Museum of Artistic Culture, and shortly thereafter began work on developing it into a research and teaching institution, renamed GINKhUK. The formulation of Stalin’s first “Five-Year Plan” of economic and cultural restructuring brought this career to a close around 1927; Malevich was denounced as a bourgeois reactionary and, worse, a monk-like obscurantist, and promptly sacked from his post.5

Kazimir Malevich teaching students at UNOVIS, 1921 –22.

On the surface, all of the academic maneuvering that leads up to this end appears to follow a familiar pattern, for already by the early twenties it had been made evident that the so-called “laboratory stage” of Soviet art would have to start yielding some concrete product. The leeway for aesthetic experiment radically narrowed from there on, as artists were challenged to submit their various findings to social implementation. One could say that Malevich’s exit from the studio and into the classroom followed the transition of advanced art in Russia from Constructivism to Productivism, but it is important to remember that he never accepted these terms. Not painting but teaching, Malevich partly complied with the order of the state and made himself useful, while at the same time campaigning in his own self-interest, stubbornly retaining his designation as a Suprematist—above all!—and converting as many others as possible to the nebulous cause.

Black Square is the epitome of what Yve-Alain Bois terms “painting as model.”6 It refers to nothing outside itself and thereby accedes to a plane of supreme autonomy. But how, then, should we qualify all of the other paintings that refer to it, beginning with the paintings of students who closely followed its model? Black Square could be, and in fact was, faithfully reproduced, and whether by Malevich or someone else is finally less relevant than the spirit in which it was done. Technically, the task poses few problems, which is exactly the point: no painterly expertise is required to produce a superficial likeness of this work, but this does not mean that it really is within the reach of everyone. Rather, its outward simplicity belies arduous mental preparation, for in order to produce a proper Black Square, one has to travel full circle with Malevich and to likewise become “the zero of form.” Self-cancellation is the first step toward the non-objective or “objectless” world of the monochrome, and upon completion one can also forsake this painting as object. Every time it is remade it is to restate this case, to preserve only the injunction to preserve nothing. This is the lesson of Malevich: the dark star of aesthetic refusal must be pursued all the way to the flaming finish.

During his years as an art educator, Malevich consistently downplayed his practical accomplishments as a painter in favor of his intellectual pursuits, and some would say for good reason.7 By any standard of measure, his painterly corpus is patchy and includes a number of works that might be declared downright bad. He often described himself as self-taught in the field, though not necessarily to insist on an innate talent. In fact, records suggest that the young Malevich repeatedly applied to the Moscow Art Academy and was denied entry each time.8 Whether this early snubbing had any impact on his sense of artistic self-worth is worth pondering, but what is more established from an art historical standpoint is that his crowning achievement, as he himself understood it, is a piece of writing titled The World as Objectlessness, composed between 1923 and 1926. Moving from the work of the studio to that of the studium, it is here, in his philosophical summa, that the painter lays out his theory of the “additional element,” sometimes translated as “supplementary element,” which holds the key to both his art and his teaching method.9

Malevich derived his “additional element” from an in-depth analysis of the succession of styles within Western Modernism, distilling from Realism, Impressionism, Post-Impressionism, Cubism, Futurism, and so on certain nascent qualities of line and color, paint application, and spatial composition that could be appropriated and further elaborated. Together with his students, he composed detailed charts made up of photographic reproductions of past works and schematic drawings that demonstrated precisely what, at every stage of art, was in the process of emerging as the latent addendum to its manifest forms. The way to zero is complicated, as mentioned; Malevich’s charts track a simultaneous movement backward and forward, a teleological skewering of timelines. These charts served ends both explanatory (for others) and revelatory (for himself). That is, they showed Malevich where to go while showing others how he got there, which is exactly how they were applied in instruction.

To the spiritual side of the “painting as model” that is Black Square must be added a (pseudo-) scientific side. The “additional element” is precisely that which is not characteristic of a style, or that which exceeds it, mutating toward the next style, and the next, though not in a manner that is necessarily progressive. That Malevich considered this quantum in clinical terms, as a kind of bacteria or virus, is especially suggestive from our current perspective within the educational complex of art. During his tenure at GINKhUK, he conformed all cultural research to medical protocols, going so far as to found a Department of Bacteriology of Art. This department, as Malevich put it in a submission to “The Work Plan of the Department of the Painterly Culture for 1926–1927,” “considers all painters as medicine considers the sick…”10 While teaching, he characterized himself as a doctor and his students as patients, an approach almost unimaginable in art school today. No doubt, Malevich took to his profession with scholarly rigor and in all seriousness, but this does not automatically imply that he took himself so seriously. I prefer to think he did not, and that all of the earth-shaking authority we make out in his voice is slyly leavened with a Chekhovian absurdism. It is said that he would perform his student studio visits attired in a starched white lab coat, administering “doses” of Suprematism to those most wanting.11

Kazimir Malevich, Analytical Chart, 1925. Cut-and-pasted papers, pencil and ink on paper, 2 1⅝ × 31 inches. Digital Image © The Museum of Modern Art/Licensed by SCALA/Art Resource, NY.

2

The sorts of “shenanigans” mentioned above made an easy target of Malevich and his ilk and only hastened the withdrawal of state-sponsored support for their artistic experimentation. The new order that followed was founded on a demand for results—design solutions or socially effective propaganda. For a considerable time, the lessons of Black Square were effaced, or rather went dormant. In the postwar years, however, the black monochrome reappeared in America, and with a vengeance, for here as well signs of ideological stress were instantly evident. This “second coming” signaled a breaking-point crisis for Western Modernism just as it had in the East, only here we are faced with a much longer timeline and hence a much slower process of unraveling. Among those who took Malevich’s teachings to heart, Ad Reinhardt stands out, not only because he committed himself to painting canvases black, or near-black, for the last fourteen years of his life, but because he likewise sealed these works behind a protective bulwark of willfully obtuse theorization. Like Malevich, Reinhardt would be characterized as monkish: the “black monk,” as Harold Rosenberg called him.12

Reinhardt was born in Buffalo, New York, to immigrant Russo-German parents. Remarkably, his birthdate, 1913, coincides with the first appearance of Black Square; this fact is acknowledged at the start of his self-penned “Chronology,” and we might remember as well that the date transitions toward the start of World War I.13 On all fronts, then, one could say that Reinhardt came into a world of trouble. From here on, his project was set: to protect the aesthetic sphere from “ideological struggle,” as Clement Greenberg put it in his breakthrough essay “Avant-Garde and Kitsch,” tellingly published in 1939, at the outset of a second round of total war.14 In “Toward a Newer Laocoön,” penned just one year later, Greenberg restates his case more adamantly, arguing that what is to be strictly avoided by artists are “ideas” as such, for these could now only be seen as “infecting the arts with the ideological struggles of society.”15 Reinhardt subscribed to this view, but only to an extent. The vaunted purity of his work is, from the first moment, riven by conflict; it is no less “infected” than that of Malevich, to which it owes an obvious debt, while also presenting some notable points of divergence.

The modern history of art, as Reinhardt sees it, is concisely articulated in his 1962 essay “Art-as-Art,” an early entry into his foundational “dogmas”: “The one intention of the word ‘aesthetics’ of the eighteenth century is to isolate the art experience from other things. The one declaration of all the main movements in art of the nineteenth century is the ‘independence’ of art. The one question, the one principle, the one crisis in art of the twentieth century centers in the uncompromising ‘purity’ of art, and in the consciousness that comes from art only, not from anything else.”16 Whatever socially redemptive optimism we can still make out in Malevich’s argument is here eclipsed; in Reinhardt’s view, everything now converges upon the separation of art from every other sector of our experience. To put a negative spin on Malevich’s bacteriological analogy, this process could be compared to quarantine. “The one place for art-as-art is the museum of fine art,” Reinhardt writes.17 In direct opposition to the avant-garde call for the “supercession” of art, and/or its integration into everyday life, Reinhardt affirms: “The one thing to say about art and life is that art is art and life is life, that art is not life and that life is not art.” His opening line effectively says it all by way of a series of tautologies: “The one thing to say about art is that it is one thing. Art is art-as-art and everything else is everything else. Art-as-art is nothing but art. Art is not what is not art.”18

Society is categorically refused in Reinhardt’s black paintings, which pursue an agenda that belongs to art alone, outside any explicit ambition to change the world. Yet it is well known that this artist, who grew up in a left-leaning working-class household, remained throughout his life politically committed and active. He just made a point of leaving his politics outside the studio door. No doubt, his early experience working as an editor, columnist, illustrator, and layout designer for a number of socialist publications, PM and New Masses among them, contributed to his sense that politics are best pursued by other, specifically non-art, means. The implicit assumption here is that artists interested in wielding some social clout might want to compartmentalize their activities. In the context of Russia after the revolution, artists may have felt that they had a stake in the formation of the general culture, but to go on thinking this way in postwar America could only be considered naïve. A culture that is “for” society and directs the course of its development already existed, for good and ill, and Reinhardt’s art would play no part in it.

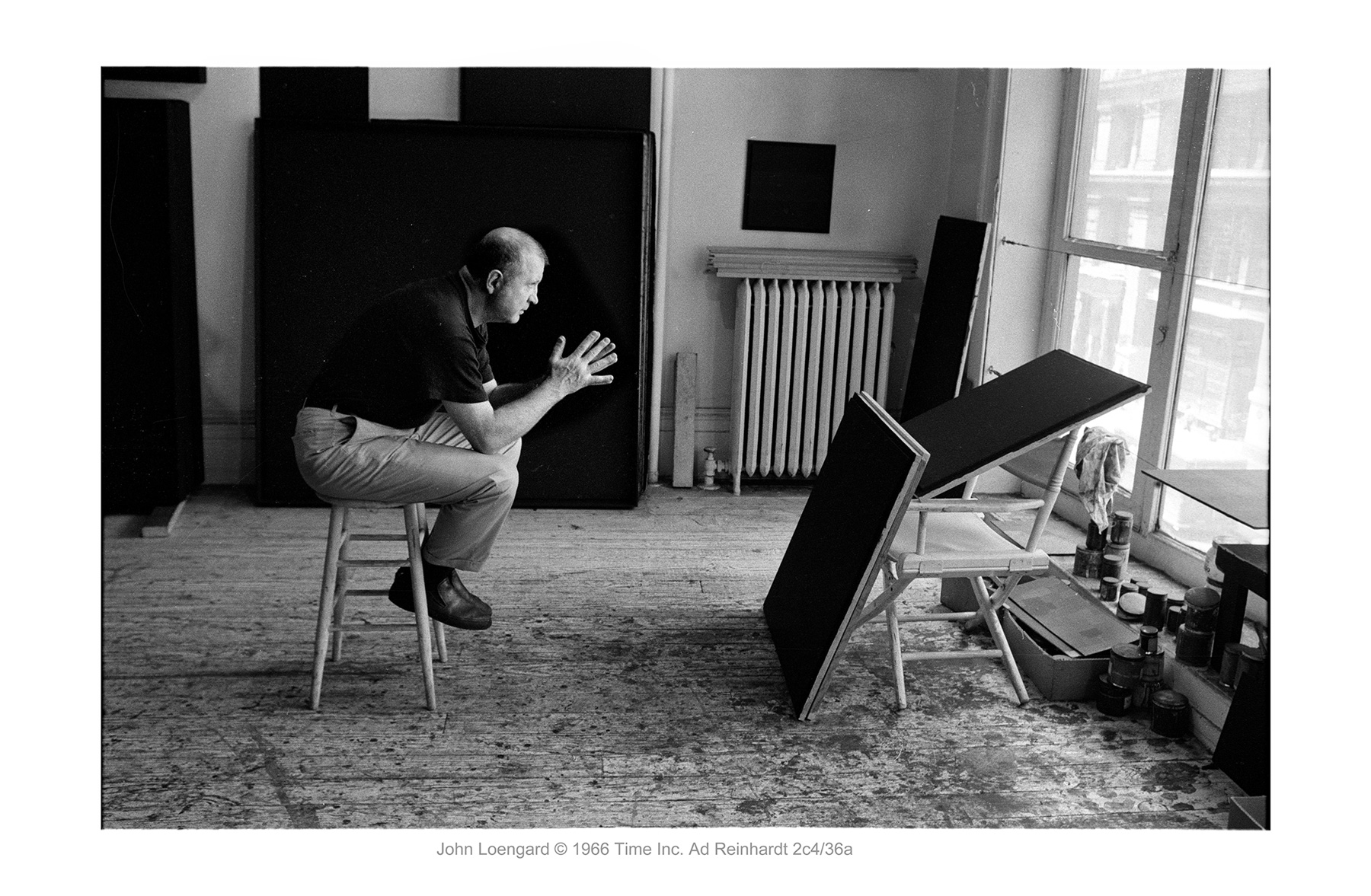

Ad Reinhardt in his studio in New York, July 1966. Photo by John Loengard/The LIFE Picture Collection/Getty Images.

Reinhardt began teaching in 1947, at Brooklyn College, and continued to do so, often traveling between institutions, until he was felled by a heart attack in 1967. By his own admission, teaching was mainly a means to make money, which might strike some as callous. But the reasoning behind it was high-minded: to relieve his painting from any financial burden. The same can be said for his editorial columns and cartoons: these are merely the products of a day job, not the vocation. And yet he approached all of these extraneous occupations with an ambition that cannot be confined to the realm of the strictly professional. As Reinhardt puts it in a catalog statement from 1949, “Contradictory as though these roles may seem, they can be viewed as aspects of a unified stance.”19 Work inside the studio could feed into the work outside it, and vice versa. Every one of his black paintings is at once a supremely autonomous object, mutely receding from “the ideological struggles of society,” and a hyper-rhetorical construct, suffused in contrarian bile. The crisis of Modernism that these signaled is not just that of de-skilling and de-composition—the reduction of painting to the Greenbergian nadir of a “tacked-up canvas” that perpetually reasserts the dumb facticity of its material makeup—but also the elaborate theoretical scaffolding that this deconstruction would demand.20 Reinhardt probably fell afoul of his New York School colleagues on both counts, and no doubt this is also why he was celebrated by the subsequent generation of polemically minded Minimalists.21

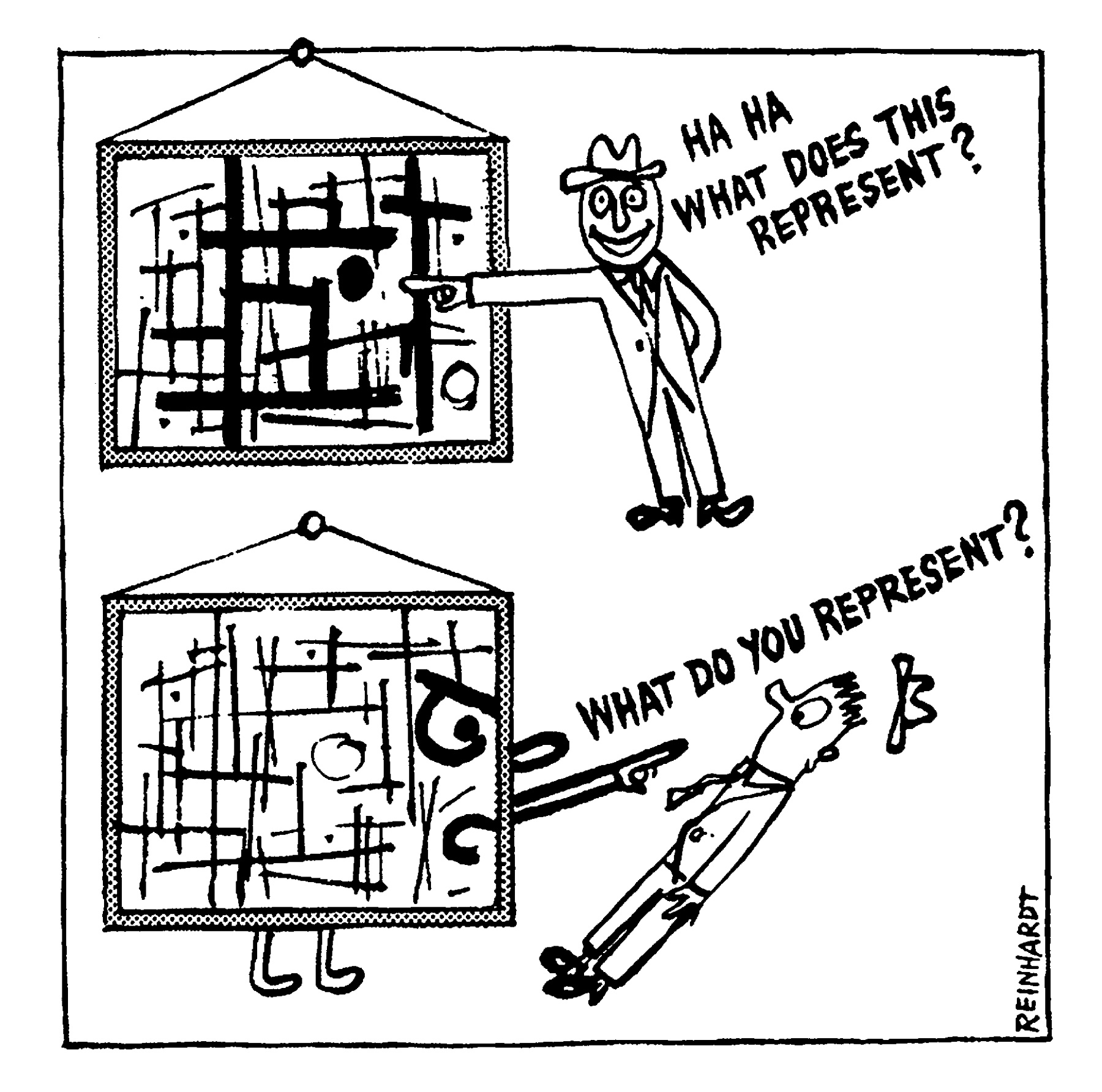

Inside the classroom, one can imagine Reinhardt himself sternly posing to students the question that issues from a modernist painting in one of his best-known cartoons: “What do you represent?”22 In the context of art school, the correct answer would have to be “nothing!” Here we devote ourselves to abstraction; we plumb “the zero of form;” we open the way to “the world as objectlessness.” For Reinhardt, this required not only voiding painting of any explicit ideological message, but also detaching it from the implicit ideology of the art market, from “the umbilical cord of gold,” in Greenberg’s words, that connects art to the patron class.23 “I tried to oppose the academic to the market place,” Reinhardt explains in an interview from 1966. “I think in the future I see mainly the university academy as the proper place for the artist because the market place is insane.”24 If the good virus of the “additional element” had now met its most daunting antagonist in the capitalist economy, then the solution can no longer be a Black Square for everyone. This is how Reinhardt rewords the lesson of Malevich: “This painting is my painting if I paint it. This painting is your painting if you paint it.” Is it also yours if you simply buy it? Basically Reinhardt says no, “with few exceptions.”25 Reinhardt taught to make ends meet, but he also did so in pursuit of the teleological end, for the void hollowed out by his work is here filled with words, and these serve to communicate the social promise, however attenuated, of via negativa. To refuse society as it is points to self-centered, “holier than thou” withdrawal, but inside the ivory tower of academia a vision is shared of the society that could be if everyone else refused as well. Of course, Reinhardt did not believe that this vision could ever be realized, not even in the limited context of art school. Note that he set aside this place as a proper one for the “artist-as-artist;” the general art student body, who may have already been thinking of their debt in terms of investment, was another matter.26 Anyone too beholden to society could not have been on his side. It is in this spirit that Reinhardt proudly declared that, after almost twenty years of teaching, “I’ve never been called a good teacher.”27

Ad Reinhardt, How to Look at a Cubist Painting, published in P.M., January 27, 1946 (detail). Artwork © 201 6 Estate of Ad Reinhardt/Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Courtesy of David Zwirner, New York/London.

3

Moving forward another generation or so, monochrome painting, or any painting for that matter, would no longer figure so highly on the list of educational priorities—especially not in the post-studio department at California Institute of the Arts (CalArts). Founded in 1970 by dean Paul Brach, his assistant Allan Kaprow, and newly hired faculty member John Baldessari, this part of the school was to cater specifically to “students who don’t paint or do sculpture or any other activity done by hand,” as Baldessari explains in Richard Hertz’s oral history of the period.28 But let’s also remember that Malevich’s Black Square was from the first moment proposed as a model for painting as well as not painting.29 One could always produce further Black Squares, and thereby repeat the order of the first last painting from the perspective of “the last things before the last,” in the words of Siegfried Kracauer, or else one could simply cut to the chase. 30

Before the inception of his post-studio program, Baldessari had put in his time wrestling with the medium, but then suddenly decided to send his painterly oeuvre up in smoke. This drastic move, which laid to waste over one hundred works, resulted in one “last thing”: a modest funerary urn and corresponding plaque bearing his name and the dates “May 1953” (his college graduation) and “March 1966” (his turn to Conceptual art). The event that yielded the Cremation Project , as it came to be titled, occurred on July 24, 1970, just prior to the start of Baldessari’s first semester as a teacher at CalArts. This timeline is suggestive, for it sets his teaching practice on a tabula rasa of scorched earth. All the way to the flaming finish: certainly, here the lesson of Malevich still holds some sway, for isn’t the crematorium perhaps the secret site of his dark star’s apotheosis as supernova? If so, then we arrive at a “zero” of a quite different sort, one that will not lend itself to any further subliminatory treatment. If we accept the Freudian line that all art is a form of sublimation, offering a socially acceptable outlet for often perverse and agonistic drives, and if further we characterize formalist art as the sublimation of sublimation itself, then here we must consider at least a modicum of de-sublimation, a return of the real. Perhaps this is just what Baldessari meant when he wrote, “I will not make any more boring art” over and over into a spiral-bound note book in his 1971 video of the same name. By the seventies, the modernist ideal of Kantian disinterestedness had become merely uninteresting; the social stakes of art would have to be raised.

John Baldessari with plaque from Cremation Project, 1970. Courtesy of John Baldessari.

In Baldessari’s video, the good teacher is presented as a bad student, or perhaps it is the other way around. Whichever is the case, this work suggests that art and school have become more closely imbricated than ever before. In the list of assignments Baldessari drew up for his post-studio class at CalArts, it is quickly made clear that the former bad is the new good, and again not just in relation to a formal analysis of art making, but also to the general comportment of students on campus and in the world. Of the 109 options that he circulated among his young charges, a good number cross the line of legality, involving such things as impersonation (“1. Imitate Baldessari in actions and speech.”), lying (“4. Write a list of art lies,un-truths that might be truthful if we really thought about them.”), obstructionism (“18. Subvert real systems. …Put a sign that says slow in the middle of a street.”), theft (“29. Have some take photo portrait of you just before you go into a store to steal something. Have your portrait taken immediately after the act. Photo the object stolen.”), vandalism (“34. Defenestrate objects. Photo them in mid-air.”), and forgery (“43. Forgeries. Ea[ch] in class tries to forge my signature on a check by looking at an original.”).31 The point of these exercises was obviously to rid students of their aesthetic preconceptions and tastes, to “think backward” as Baldessari writes further on in the list, and yet it is telling that this guided break with the disciplines of painting and sculpture and “any other type of activity done by hand” should lead so swiftly to a more general sort of insubordination, a succession of social transgressions. It is as if the post-studio assault on the prior order of art, which could no longer be absorbed by all those media now disallowed, could only escape into a world where symbolic acts have real, and sometimes dire, implications. To read this document today, when teachers have to take out insurance to mount an innocuous museum field trip, is doubly thrilling.

Art school has long served as an intermediate station between lofty ideals and worldly corruptions, but at CalArts, in the seventies, it could no longer be considered a space of reprieve. Post-studio art, while still in its infancy, was directed into society and often against it, and this effort inevitably reflected back upon the contradictions inherent in art school itself. How does one go on thinking anti-business like Reinhardt in what is becoming basically a service-sector industry? The solution proposed by Baldessari’s assignment list could be seen as a form of acting out, at once burlesque and quixotic. Michael Asher, who joined the post-studio team at CalArts in 1973, would take a more introspective approach, in regard to art-institutional matters, with his legendary critique class. The first thing he did was “throw away the clock,” as he explains in a 2006 interview, because “there is never enough time to get everything said.”32 The resulting marathon sessions of analysis served to focus student attention utterly upon the work of art by limiting access to anything outside it. What if there really was nothing outside art, or to put it in Asher’s more pragmatic terms, what if we simply made no time for it? This is a utopian initiative, to be sure, but that does not mean it will be agreeable, let alone fun. The utopia of art is here met in both empty and full time: a time that dumbly elapses, winds down, amidst agonizing stretches of silence, and a time that ecstatically gains as it approaches its end, unmarked and unnoticed—the end of this class (0), and beyond it (0,10) all classes, all schedules—the end of times.

Michael Asher with Tom Jimmerson and David Askevold at LAICA, 1977. Courtesy of CalArts archive.” “Photo: Bob Smith.

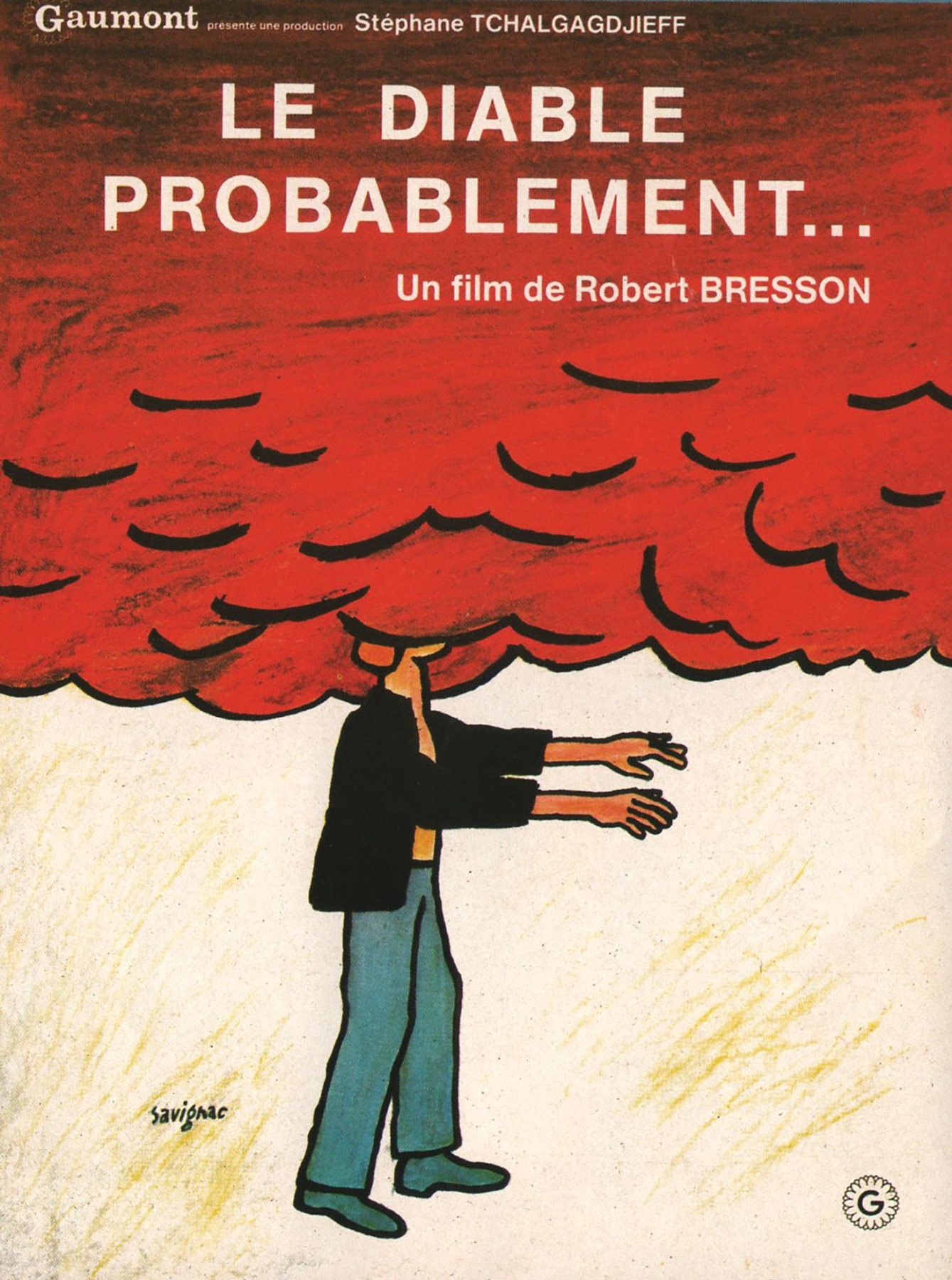

Boredom, the principle drawback of every utopian plan upon realization, must be preemptively embraced in the art institutional setting. This is one of Asher’s key lessons, and his student Stephen Prina systematically applied it in another highly influential class, this one taught at Art Center College of Design in the nineties. “For years I had wished to offer a class the structure of which would allow me to screen the same film week after week,” the artist recalled in an Artforum essay from 2000 that commemorated the work of the then-recently deceased director, Robert Bresson.33 The film that was played on repeat in the school auditorium was Bresson’s Le Diable, Probablement (1977), which follows a group of disaffected youths through the streets of Paris as they erratically renegotiate the battle lines that had seemed so clear to the prior generation of huitards. Certainly, this was a historically targeted selection in regard to these students, most of whom would have been born into the post-May 1968 moment that this film subjects to rueful scrutiny. Perhaps there is a measure of cruelty in having Bresson restate his case, over and over, to the next generation: the world you have inherited is post-idealistic and, even more damningly from any young artist’s vantage point, post-avant-garde. At any rate, this could be a topic to take up in class discussion, but it also suggests that anything could be discussed in class. Another seminar conducted by Prina on the filmography of Keanu Reaves was even more emphatic on this point. The search for art-appropriate subject matter that had directed the entire course of Modernism toward the zero degree suddenly switched into reverse. The former void became a sucking vacuum, and a new challenge emerged: it was no longer how to avoid talking about what everyone else talks about, but how to do so differently.34 At a time when the old avant-garde mantra, “Every man is an artist,” has been appropriated by every sector of the economy, and art school threatens to become just another arm of the creative industries, the need to extract from the anything and everything of the world something else—a new strain of the “additional element”—becomes all the more pressing.

Raymond Savignac, poster for the film Le Diable Probablement, directed by Robert Bresson, 1977. 62 x 47 inches.

4

The Soviet example sets the mold: the hands-off interregnum of any “laboratory stage” is typically short. In the American context, the demand for artistic “results” will come not from state apparatchiks but the corporate sector. The seemingly limitless growth of art schools at present obviously answers to market calculation. At the University of Southern California, the forced merger between the Roski School of Art and the recently established Iovine and Young Academy—which counts “art” as a principal area of concentration right alongside “technology” and “the business of innovation”—portends the triumph of instrumental reason over experiment. 35 It is certainly a worst-case scenario, but by no means unprecedented, for what has happened there points to problems endemic to art school. Let’s not forget that CalArts was actually built by the culture industry, to channel young talent straight into the Disney studio system. The radicalism of the post-studio program, the vehemence of its refusal, was partly developed in answer to that.

Art departments must always contend with other, often more commercially integrated and therefore more secure, departments that surround them. One could say, further, that if art school is to work as it should, it is precisely by not working as other schools do and, to put it more generally, by not working as the world does. In this sense, art school, in order to maintain its integrity, also partly invites its own destruction. The particular version of the utopia of art that occasionally takes root in an institutional setting is, as we know, a contentious one from the start. It does not on the whole agree with whatever lies outside the perimeter of its “magic circle”—the rest of the school, the rest of the world—and neither are those inside necessarily in agreement as to the nature of this disagreement. From the outside perspective, the internecine struggles of art school might seem absurd, especially when they are driven by ideological, rather than strictly administrative, concerns. This is perhaps just as it should be, and in this regard we might more accurately define the utopia of art school as a heterotopia, in the sense that Foucault meant it—that is, a place of carnivalesque inversion, and one that is inherently provisional. 36

The order of the heterotopia is, by definition, volatile. It is not decreed democratically and certainly not by committee. If we consult the historical record, we find that all of our most revered art schools—alongside those already mentioned, the Bauhaus, Black Mountain College, Nova Scotia College of Art and Design, etc.—experienced their productive apex under the leadership of individuals unilaterally appointed, rather than elected, to their post. And, as it turns out, the chief qualification for the job was rarely responsibility, fairness, or compassion, let alone “the vision thing,” as George H. W. Bush dismissively put it in a 1987 Time magazine article. Rather, it would seem that many of these people were driven by some measure of righteous perversity. Sadistic? Masochistic? Probably both; whatever it takes to turn the world upside down.

To be clear, upending the order of things in this way should not merely provide us with a recipe for “thinking outside the box.” The greatest dangers facing art school at present stem not only from institutional opposition to the radical lessons of the past, but also from their cooptation and normalization. The bad student makes for a good teacher, as mentioned, and this might recall the ideal figure of the “ignorant schoolmaster,” as Jacques Rancière would have it.37 But I would like to stress a point that Rancière’s text, in its current art school implementations, often allows us to overlook. Has it not become imaginable today that the sort of ignorance that this philosopher cherishes may in fact be closer to the safe shores of the status quo than its revolutionary horizon? Those who follow this model are obviously not hapless pedagogues, but elected representatives of the school-attending public, whom they organize—rather than teach, with all its top-down implications—into a collective forum that can then determine its own curriculum. This obviously sounds good on paper, but paper is also perhaps the only place where it sounds good. Far from suggesting that Rancière’s ideal is unrealizable in practical terms, the problem is rather its all-too swift implementation as paperwork. From the perspective of art school administration, the “ignorant schoolmaster” is the safest bet, the one least likely to generate a complaint. After all, who did not prefer that teacher in high school who asked, just like the first Apple computers, “Where would you like to go today?” Back then, it was perhaps a perception of institutional insubordination that seduced us; now that this approach is sanctioned, even demanded, hasn’t that alluring glimmer of mischief been eclipsed? The “ignorant schoolmaster” is just angling for a decent student evaluation, and I’d be the last one to blame him, because I do it too.

It is to this nominally user-friendly environment that art school has perhaps incurred its greatest losses. The list could go on of pedagogical approaches, once perfectly germane to the field, that have turned egregious by current standards. Certainly, it would be a worthwhile project to provide a fuller, and more nuanced, accounting of these at some point, but here I will furnish only two more. It was not so very long ago that Charles Ray would convene group critiques in his office at the University of California, Los Angeles, crowding the small room with student bodies, and then turning the light off. The object of this exercise was probably to remind them that art exists in the memory and imagination, but that we remain all the while physical beings. Nancy Rubins may have been thinking along related lines when, at the same institution, she had students make a piece based on their weight as her introductory sculpture assignment. (This process began with having the students mount the scales one after another!)

Here again we might be reminded of Malevich’s work at the Department for Bacteriology of Art, where the teacher “considers all painters as medicine considers the sick.” In his treatment plan, Malevich was evenhanded; if he did not specify its application to students, it is because he considered students as artists, and vice versa. In effect, he presented himself as the ultimate artist-as-student, and hence also the one in the best position to administer the cure. To reverse this protocol via the figure of the ignorant schoolmaster is increasingly to rehearse the literally shopworn saying, “The customer is always right.” For students to approach their education in this way, as righteous customers, is to guarantee that nothing will be learned in the end about art, or about society for that matter, where the assumption is proven false from the first moment. Sham empowerment—this is merely a selling point, a shopkeeper’s strategy, and precisely the virus that one should be inoculated against. If history teaches us anything in this regard, it is rather that the customer is never right.

What a guilty pleasure it would be to transcribe those words into a syllabus, when in fact we are asked to produce something more akin to a legal document, a liability waiver, just another airtight page to fill the exponentially expanding folder marked “risk management.” Perhaps even worse is the demand to provide an indication of “learning outcomes,” especially when this means aligning the lessons of class with a range of real-world competencies. There is no end of art-related occupations that could, at this point, serve as potential student objectives; however, these will surely drive us off the road. That the critical methods of art school can now be applied across the board is confirmed in best-selling books by the likes of Malcolm Gladwell and Daniel Pink, but if it really is true that “the MFA is the new MBA,” as Pink has repeatedly declared, then this might be a sign to draw back.38 Any art school that has instead seized upon this cultural turn as an opportunity for expansion, rebranding itself as a growth industry, becomes something else—anything and everything else. Let’s leave it to others to convert the lessons of the great revolutionary struggles of the twentieth century into the design of a “better mousetrap” for the twenty-first. And let’s avoid nostalgia as well; the point is not that art school was better back in the day, but that it was always to some extent bad. The way to zero is not, and has never been, just a way backward or forward. At every stage in the historical process, the teleological end, the final cause, must be recalibrated through a new round of refusals.

Jan Tumlir is an art writer who lives in Los Angeles. He is a founding and contributing editor of X-TRA. His most recent book, The Magic Circle: On The Beatles, Pop Art, Art-Rock and Records, was published by Onomatopee, in 2015. He teaches in the MFA department of Art Center College of Design and is presently a Wallace Herndon Smith Distinguished Scholar at Washington University in St. Louis.