Ontology –once it is finally admitted as leaving existence by the wayside– does not permit us to understand the being of the black…

—Frantz Fanon, The Fact of Blackness

For all of the vibrancy of the community described by black artists who lived and worked in Los Angeles in the 1970s—including the exhibitions at the Brockman Gallery, gatherings at Studio Z and Othervisions Studio, and collaboration throughout the city—mainstream critical writing’s treatment of these artists and the scene that incubated them merely skims the surface. Certainly a number of these artists have, after the fact, gone down in history as important figures. Among them are Senga Nengudi, Barbara McCullough, Fred Eversley, Noah Purifoy, Betye Saar, Charles White, and David Hammons. But many of these artists’ careers skew in the direction of being “hometown heroes” in Los Angeles; they are ghettoized to consideration primarily when the art world wants to think local—a consistent trend when it comes to considering art that comes out of Los Angeles—or to think along racial lines.

Video and performance artist Ulysses Jenkins is but one of these under-recognized artists, despite his large and potent body of work and his involvement in collaborations with many artists throughout California through the collective of Othervisions Studio, Electronic Cafe International, and other initiatives. Jenkins, now a professor at the University of California, Irvine, has been included in retrospective exhibitions such as Now Dig This! Art & Black Los Angeles 1960–1980 (Hammer Museum) and Radical Presence: Black Performance in Contemporary Art (Contemporary Arts Museum Houston). But when his work is discussed, it is almost always in passing—garnering no more than a few paragraphs of interest, the bulk of which considers it a commentary on positive and negative representations and stereotypes of black life1 — a fate that befalls many a black artist.

Ulysses Jenkins, Mass of Images, 1978. Still from video transferred to DVD, black and white, sound, 4:15 min. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ulysses Jenkins.

These readings of Jenkins’s work lean heavily on his 1978 video Mass of Images, a recorded performance that does indeed engage black stereotypes perpetuated by the American media. In the work, Jenkins appears on a set accompanied by a stack of televisions, his face obscured by a plastic mask and sunglasses, neck wrapped in American-flag-print scarf, and sporting an Adidas t-shirt underneath a bathrobe, arranged such that only the “ID” of Adidas is visible. The video cuts between this scene and examples of blackface and racist stereotyping from American films and TV. Jenkins repeats a mantra as he settles into a wheelchair and wheels himself toward center stage: “You’re just a mass of images you’ve gotten to know / from years and years of TV shows. / The hurting thing; the hidden pain / was written and bitten into your veins / I don’t and I won’t relate / and I think for some it’s too late!”2

Continuing the refrain, he gathers his strength and rears to smash the TVs but falters. He gasps and laughs, rather manically, and says, “Oh, I’d love to do this, but they won’t let me.” He turns toward the camera, repeats the mantra one more time, and then the screen goes dark.

The few published texts on the work that are in circulation—and they are minimal—focus on the inserted panels featuring images of Hattie McDaniel in her all too familiar mammy guise, Bert Williams in blackface, Allen Hoskins playing “Farina” in The Little Rascals, and other instances of blackface and racist imagery. The authors argue that Jenkins aims to illustrate the possibility of overcoming the power of these representations. In the catalog for Now Dig This!, for example, Roberto Tejada focuses on Jenkins’s regaining of his composure following his outburst as signaling the “possibility of…self-possession within the mass of images that work to contain black bodies in representation.”3 However, I would argue against Tejada’s claim, because this possibility is unrealized in the work. At the video’s closing, we leave Jenkins exactly where we found him, repeating the same refrain. Other readings of the video find Jenkins generally critiquing cultural stereotypes, again performing the work that has come to be expected of the black artist of his time.4

Ulysses Jenkins, Mass of Images, 1978. Still from video transferred to DVD, black and white, sound, 4:15 min. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ulysses Jenkins.

Across all readings of Mass of Images, the lack of interest in Jenkins’s failure to destroy the television sets is surprising. If the conceptual thrust of the work is meant to be the black-artist-as-subject’s triumph over his flattened, essentialized, racist image—as readings so far have claimed it to be—then we must ask the question: Why doesn’t Jenkins smash them? He tells us why. It is because “they won’t let” him. The line “they won’t let me” betrays a wholehearted desire to commit the act. Jenkins wants to smash the televisions but someone is stopping him. This moment, this break in the otherwise meditative pacing and relative calm of the video, becomes a focal point and in turn positions desire as the unseen force propelling the work. Jenkins noted, in a 2008 interview, that he very carefully positioned the bathrobe over his Adidas t-shirt such that only the “ID” is visible to the viewer, as a sly nod to Freud, signaling that he is concerned primarily with the libidinal economy of the work.5 Here, we are not quite within the domain of ethics or politics—the domains that the Black Nationalist agenda and Jenkins’s Black Arts Movement contemporaries would have had him occupy. The only politics here is a desire to be himself.6

Focusing on this break and viewing Mass of Images as an exercise in failure, rather than a victory over representation, we follow Jenkins into a rather unusual realm of inquiry, one that makes sense to have downplayed when it comes to historicizing black art of the period. Jenkins and his Los Angeles contemporaries, such as Senga Nengudi, Maren Hassinger, Barbara McCullough, and (for a brief period) David Hammons, were often accused of making art that was not political enough or “black enough” due to their interest in new media and abstraction and their willingness to draw on sources from outside of the black tradition.7 Following Jenkins down this rabbit hole unravels much of the twentieth century’s work toward a black politic of representation and provides a counter-argument against attempts by Black Arts Movement leaders, such as Larry Neal and Ron Karenga, toward a black aesthetic and a black art that articulates a self-determined blackness through images that “speak to and inspire black people.”8 Jenkins departs from this concern over what Frank Wilderson III calls the “hegemonic value” and pedagogical power of visual representations of blackness and black people, which ruled black art criticism and black cinematic theory of the time. Instead, Jenkins is interested in questioning the very nature of blackness itself.

During the period from the creation of Mass of Images through the performance Adams Be Doggereal (1982), one finds Jenkins asking a specific set of questions. These works should be viewed as a marked period in Jenkins’s oeuvre, one that goes beyond “cultural critique,” reaching into a zone of inquiry less acceptable to the mainstream. During this period, which includes the video/performance Two Zone Transfer as well as the performance Just Another Rendering of the Same Old Problem (both, 1979), we witness a narrative unfolding, one that originates in Jenkins’s massive failure to assert a legible ontology of himself as a black subject capable of wreaking havoc over the images imposed on him and ends with an abandonment of this pursuit. By the end of this period, Jenkins—in a semi-linear progression—has moved away from grappling with the slippage between the black subject and its representation and toward a non-ontological blackness, or what he deems a new black universalism.

Ulysses Jenkins, Mass of Images, 1978. Still from video transferred to DVD, black and white, sound, 4:15 min. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ulysses Jenkins.

Let us begin again, from here. Jenkins started where many young black artists find themselves. Studying at Santa Monica College (SMC) and later at Otis College of Art and Design, “in the shadow of Hollywood,”9 Jenkins was aware of the conflicting interests of the entertainment industry and the African-American community. The works he developed following shortly after his enrollment at SMC take to task the media’s role in perpetuating these stereotypes, exploring the resultant exacerbation of a black “double-consciousness,” to borrow W. E. B. Du Bois’s terminology.10 Mass of Images is chronologically the first of these critiques, followed by Two Zone Transfer and Just Another Rendering of the Same Old Problem (1979). Two Zone Transfer follows closely in the footsteps of Mass of Images, with Jenkins zeroing in on blackface and minstrelsy’s effects on black Americans. The video, also staged as a performance at Otis College, opens with Jenkins boarding a city bus, where we witness white riders’ suspicion of him as a black man. Jenkins drifts off to sleep, and a figure in a dream says, “You know why you can’t sleep; it’s the same old problem that every black person in this country has had.” Jenkins replies: “You mean the misunderstandings I encounter, or the same old, basic image problem?”11 The “image problem” spoken of is the career-defining conundrum of black representation.

However, Two Zone Transfer marks a shift in Jenkins’s approach to the image problem, away from the traditional inquiries of first wave black filmmaking and film theory—described by Frank Wilderson as an intense preoccupation with “identifying and critiquing the recurrence of stereotyped representation in Hollywood films,”12 and exemplified in the writings of such critics as Don Bogle, Thomas Cripps, and Gladstone L. Yearwood. Instead, Jenkins looks to the source of the problem, interrogating the history of early twentieth century vaudeville. On screen, Jenkins is joined by three actors—Kerry James Marshall, Greg Pitts, and Ronnie Nichols—who wear masks in the likeness of presidents Nixon and Ford. In a strange layering of whiteface and blackface, the masks are smeared unevenly with black paint. The men brag about the history of minstrelsy in the United States and how they have, for years, manipulated and misused African-Americans’ images and culture in order to distort society’s understanding of black life.

Here, Jenkins recognizes blackness itself as an image rather than focusing on its inaccuracy when contrasted with what might be posed as an authentic black life, once again departing from the efforts of black art and cinematic theory of the time. “The image problem” is not that the image fails to correspond to reality, but that the image has partly crafted reality, inextricably linking Jenkins’s own experience—as exemplified by his earlier interaction on the bus—to popular images of blackness and black people. The developing line of thought here resonates with Frantz Fanon’s realization of blackness as some “impure product.”13 As Fred Moten reads Fanon’s “The Fact of Blackness” (in Black Skin, White Masks), blackness has always been and always will be “a function of a making that is not its own, an intentionality that could never have been its own.”14

Ulysses Jenkins, Two Zone Transfer, 1979. Still of video transferred to DVD, color, sound, 23:52 min. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ilene Segalove.

Traces of this position are also visible in the earlier Mass of Images. In Jenkins’s refrain, he repeats: “The hurting thing / the hidden pain was written and bitten into your veins.” If we take “the hurting thing / the hidden pain” as a reference to suffering as a constitutive element of black lived experience, then Mass of Images shares Two Zone Transfer’s emphasis on the origin of blackness as external to itself. Here, his use of “written” could be read as a gesture toward a biologically determined blackness, perhaps a tongue-in-cheek shout out to out-of-fashion scientific racism. Jenkins is a black person, an individual of African descent. Blackness is “written” into his DNA. In contrast, “bitten into your veins” points to blackness as a virus or contagion—a theme that we find throughout rhetoric around blackness and black cultural production, from racist associations between blackness and actual disease to the tendency to laud black music as “contagious” and black joy as “infectious.” Whether “written” or “bitten,” blackness appears caught in an apparent contradiction. Jenkins, in effect, admits the seemingly paradoxical distinction between written black and bitten blackness. Jenkins himself is black in all his appearances and in his biographical experience, but his blackness is, again, an “impure product.” It is an external contagion, circulating independent of Jenkins’s own embodiment, “bitten into his veins” by mass media, engineered by white America long before his birth.

Ulysses Jenkins, Two Zone Transfer, 1979. Still of video transferred to DVD, color, sound, 23:52 min. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Ilene Segalove.

Two Zone Transfer has, in essence, a dramatic “to be continued” ending. After the history lesson in Two Zone Transfer, the video cuts to Jenkins, dressed as a preacher, delivering a sermon about the biblical figure Noah; in the following scene, he performs a rendition of a James Brown song with the actors, now unmasked, singing back-up. The video ends with Jenkins waking up from the dream and saying, invigorated, “After a dream like that, I know I’ve got direction. I know what I’m up against.”15

Imagine a commercial break, and the next episode begins.

—

Later in 1979, Just Another Rendering of the Same Old Problem opened at Otis College in a gallery that was empty except for a small table upon which sits a television set. Ulysses Jenkins, dressed as a janitor, tidies the small set while a confused audience waits for his performance to begin. Jenkins surprises them by sitting down at the table and opening a book; through his reading he discovers that “the African-American male is perceived as a sex object in the Blacksploitation [era] of the 1970s.”16

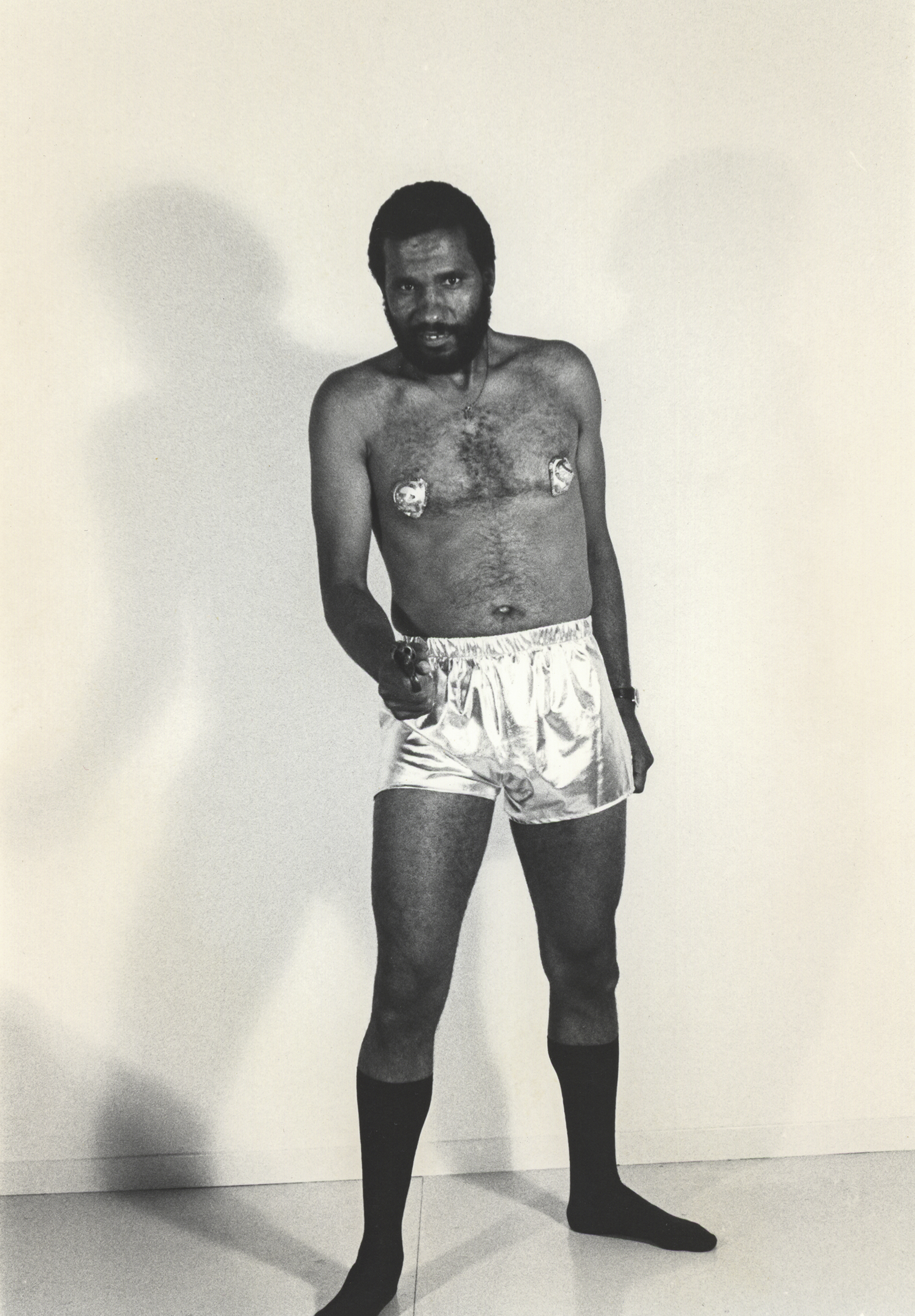

Jenkins pulls a cigar box from under the table, from which he procures a vibrating dildo. Importantly, it is a “white” dildo, with the glans, or head, painted black—a form of “blackface.” Jenkins then disrobes, “revealing pasties with Superman’s “S,” a rhinestone in his bellybutton, and silver boxer shorts,”17 suddenly embodying the sexualized black male that he’s read about. Jenkins reacts by pulling out a fake pistol and shooting the dildo. The dildo falls into the view of a closed-circuit video camera, which in turn magnifies it on the monitor’s screen. It visibly gyrates from the impact of the shots. As recounted on Jenkins’s website, “the artist realizes [that this is] the perception he confronts in contemporary society and continues [to] shoot the dildo. This stereotype won’t die…so he realize[s] he has to manually turn off [the television] and walk away.”18

Ulysses Jenkins, Just Another Rendering of the Same Old Problem, 1979. Performance. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Nancy Buchanan.

The entire scene echoes “The Fact of Blackness,” in which Fanon writes: “I came into the world imbued with the will to find meaning in things, my spirit filled with the desire to attain to the source of the world, and then I found that I was an object in the midst of other objects.”19

In “The Case of Blackness,” Moten argues that “The Fact of Blackness” is a mistranslation; it should read: “The Lived-Experience of the Black,” which would more openly signal Fanon’s phenomenological interests. Moten narrates Fanon’s realization of the ontological impossibility of a black subjectivity within civil society.20 Fanon argues, “The black man has no ontological resistance in the eyes of the white man.”21 Ontology—by way of Hegel—is attainable only when a consciousness confronts an “equally independent and self-contained” other. “Moreover, this other must have ‘nothing in it which is not itself the origin.”22 For the black (non)subject, this is an impossibility from the outset, as blackness itself is a condition whose very existence is contingent upon and derived from whiteness, making “the black” an always already impure other. In Just Another Rendering of the Same Old Problem, Jenkins thus parallels Fanon; the artist realizes that he himself exists at the limit—and beyond the limit—of ontology, unable to overtake his own representation, in this instance, as a sexual object. Caught in a literal closed circuit of representation between the dildo, its image, his own body, and the text that describes the processes acting upon him, he is left with no ability to contest his own objectification. Exhausted by his ongoing battle with the black image—which is exemplified in this work and others, as well as in his day-to-day life—Jenkins withdraws fully.

Jenkins moves on to a much larger question, an inquiry that entirely exceeds cultural critique. Now freed from the stalemate between black life and the white gaze through his own withdrawal, he asks: If blackness cannot be in the eyes of civil—white—society, if black people cannot articulate themselves as a black individuals, untethered to blackness, then what is it, in fact, to be black? What is the character of blackness?

Ulysses Jenkins, Just Another Rendering of the Same Old Problem, 1979. Performance. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Nancy Buchanan.

As Jenkins approaches Adams Be Doggereal in 1981, he has already parsed out the difference between blackness and the black individual, and understands the ontological impossibility of the latter. He has renounced his desire to just be himself, understanding now that he, as a black man, is always already “All Blacks,” as Fanon would say. Or, as Cedric Robinson wrote, Jenkins has renounced actual being for an acceptance of the historical being, the “ontological totality.”23 He has always already “consent[ed] not to be a single being.”24 As Kara Keeling writes, “The Black therefore exists as a collective subject whose governing fiction is not personal but social.”25

With this distinction in mind, it is difficult to find the exact language to speak of where Jenkins finds himself at this juncture, for his concern appears at once as neither for “the Black” nor for blackness, as well as for both the black and for blackness. This is to say, Jenkins is thinking the gap between the two, or as Fred Moten so eloquently phrased it in “The Case of Blackness”: “[T]he wary mood or fugitive case that ensues between the fact of blackness and the lived experience of the black and as a slippage enacted by the meaning—or, perhaps too ‘trans-literally,’ the (plain[-sung]) sense—of things when subjects are engaged in the representation of objects.”26

Moten, too, lingers in the gap, in the mistranslation of Fanon’s “lived-experience” as “fact,” of the phenomenologically black and the ontologically-voided blackness. Thinking this gap, Jenkins builds upon Fanon and anticipates Moten’s similar negotiations, resonances that situate him within some sort of Afro-pessimist/Black Optimist tradition27 (if we can even claim there is such a tradition). In this continuum, Afro-pessimism is something like a “[theory] of black positionality” that spreads outward from Fanon’s (non)ontology rather than a school of thought.28 Moten writes that one of the great beauties of Afro-pessimist thought is that it “allows and compels one to move past that contradictory impulse to affirm the interest of negation and to begin to consider what nothing is.”29 This is where we find Jenkins in Adams Be Doggereal.

In the performance, Jenkins’s nothing, his approximated black nothingness, takes the form of the glass prism, collectively discovered by the artist and his collaborators in a pile of dirt in his studio. Jenkins recalls the object as symbolizing a “new self.”30 The prism is materially present yet curiously empty, its primary function being to act as a filter for light. A prism can be used, as Sir Isaac Newton discovered long ago, to reflect and refract light—that is to disperse white light into beams of different colors. Prior to Newton, it was believed that white light was colorless; his experimentation with prisms proved that it was quite opposite, that it is comprised of all of the colors of the rainbow.

Ulysses Jenkins, Adams Be Doggereal, 1981. Performance. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Bruce W. Talamon.

Jenkins’s use of the prism can be theorized in a number of ways, all of which might be said to negotiate the simultaneous plentitude and void that blackness presents. First, we might read the prism as a filter of sorts, where blackness might be a lens through which to view the world. We see a similar position in William Pope.L’s Black Factory. On the occasion of that work’s first instantiation, Pope.L declared that “blackness is a lever to talk about otherness, …just a funnel.”31 A prism is a starting point from which to think a multitude of positions—a rather humanist, multiculturalist conclusion. Second, Jenkins might be proposing a radicalized departure from Pope.L’s stance, one where the prism—considering its role in proving that white light is not colorless—might speak to the notion that all other positions have been and must be articulated through and against “the Black.” This, again, follows in the Afro-pessimist line of thinking, where blackness is the non-communicable body against which white civil society constitutes itself. Third, the prism rests between emptiness and fullness. It is, as noted above, at once materially present and transparent; it also contains the potential for the apparent emptiness of white light and fullness of the rainbow. In this case, it embodies the paradoxical emptiness and fullness, plenitude and nothingness of a black (non)ontology.

Looking back upon his own work from this period, Jenkins says that his goal was always to illustrate the possibility of a new black universalism.32 It is impossible to say whether this was fully realized—or what that would even look like in practice. However, we can say that, in Adams Be Doggereal, Jenkins does realize some sort of expansion of blackness that begins to repair or move beyond its originary ontological failure. The prism effectively positions blackness as a stance from which all else must be thought, much like François Laruelle’s uchromia, wherein we might “think from the point of view of Black as what determines color in the last instance rather than what limits it.”33 From here, blackness, in all of its para-ontological glory, destabilizes not only its own existence but also all other racial ontologies that it exists to constitute. And from here, thinking “blackness as what determines color,” blackness as the starting point and not the limit, we might throw into question other artistic and philosophical interests in the color itself—and therefore reassess the position of all those whom it marks as well. Thinking of blackness, “the Black,” in this way activates its darkness and allows a consideration of its depth, its ability to reflect and absorb. As Laruelle writes, “a phenomenal blackness entirely fills the essence of man.”34

Aria Dean is an artist and writer living in Los Angeles, CA.