I was surprised to learn, when I moved to Philadelphia in 2004, that the region around the city has been something of an incubator for modern design. In the middle decades of the last century, and in proximity to ur-modernist architect Louis Kahn, the designers George Nakashima, Antonin Raymond, Harry Bertoia, and Wharton Esherick, among others, established studios in the suburbs surrounding the city. All of these designers were interested in extending the modernist vocabulary, and their works informed modern American design with a designer-craftsman sensibility and, most significantly, contributed to an expansion of conception, material, and method. Esherick’s studio and house in Paoli is now a museum and is open to the public, as is Nakashima’s studio in New Hope.

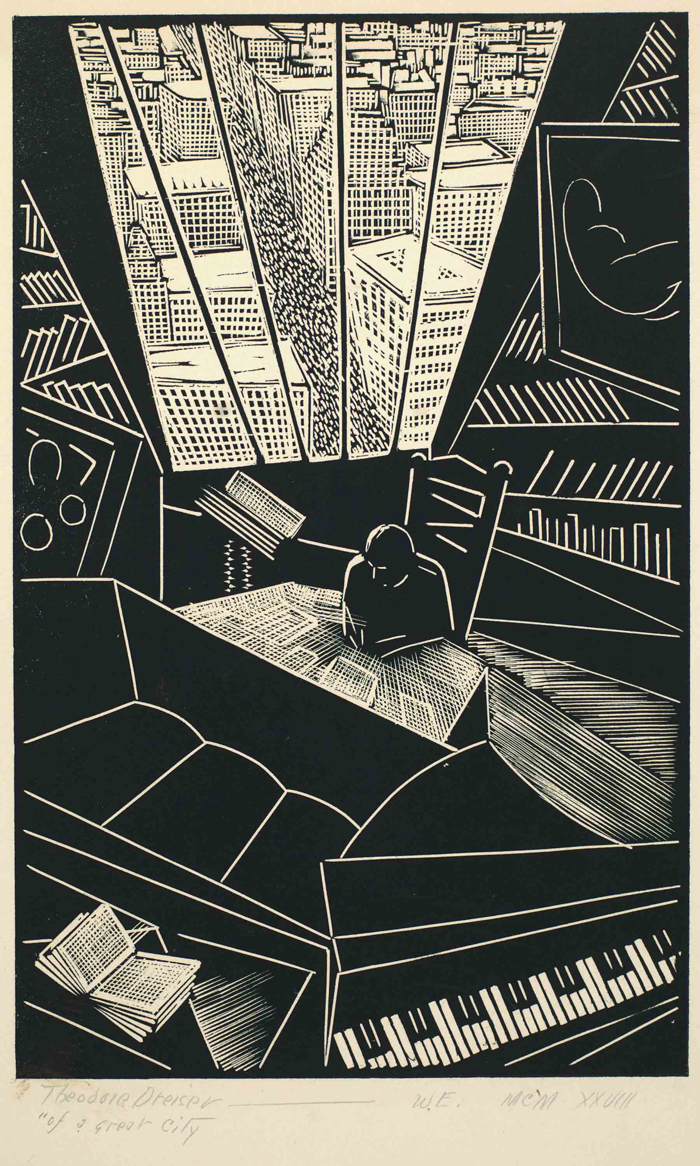

Wharton Esherick, Of a Great City—Theodore Dreiser, 1928. Wood engraving. Theodore Dreiser papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania. Courtesy Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

In this list, Esherick is perhaps the least known and, in fact, his modernism is less mid-century than the others, having begun earlier and leaning more towards an idiosyncratic hybridity. Over the course of his career, Esherick incorporated Arts and Crafts, Cubist, and Expressionist elements, along with Japanese influences, among other inspirations, and prefigured the revival of wood-craft and studio- based furniture making that was such a potent component of mid-century design by Charles and Ray Eames, Paul McCobb and others. Esherick’s works exhibit an organic flair that also anticipates some 1960s countercultural styles; his own work from the sixties and seventies, for which he is best known, is placed firmly within the history of craft—as opposed to design.1 His objects show an evolution from a somewhat conventional sense of formal design to a fully conceptualized and distinctive understanding of space and its configuration for living. The recent exhibition, organized by the University of Pennsylvania Libraries and the Architectural Archives of the University of Pennsylvania in collaboration with the Wharton Esherick Museum and Hedgerow Theater, gathered paintings, prints, drawings, objects, furniture, and ephemeral materials to demonstrate this development in the early part of Esherick’s career. The show presented, as does its catalog, a view of Esherick as a practical maker inspired by the progressive social ideas he shared with a wide and diverse circle of friends, and emphasized the impact of his experience in alternative communities on the evolution of his career.

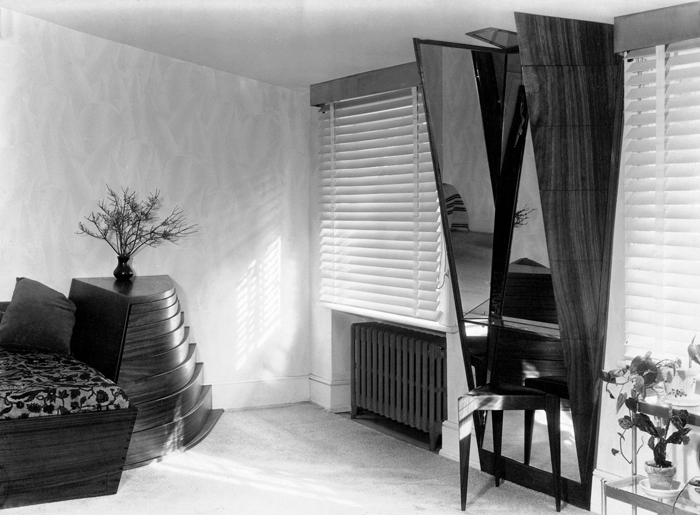

Wharton Esherick, Theodore Dreiser’s Padouk Table, 1928. Theodore Dreiser papers, Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania. Courtesy Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

Esherick is considered the father of American studio craft, and he provided a bridge between early-twentieth-century Arts and Crafts concepts of design and later, postwar practitioners. As an important figure in the history of craft, Esherick has essentially been separated from the history of modern design. The modernist thematic of Bauhaus-derived, clean-lined, industrial material and direct functionality that came to dominate mid-century design (in many design publications and in exhibitions and catalogs produced by the Museum of Modern Art) excluded Esherick’s way of working as well as his handcrafted productions.2 His often unique, curvilinear, carved wood furniture, with its historical references and a great sense of sociability, had a very different appearance and seemed theoretically opposed to the streamlined and often mass-produced objects of the Eameses, George Nelson, and Russel Wright, among others. Esherick figures more importantly, of course, in the history of the region and has influenced local designers and architects—an impetus for the project at Penn, which has a very strong architecture and design program and an active design archive. The array of material in the exhibition provided an extensive view of Esherick’s context, his influences, and his early formative projects up to 1940, stimulating consideration of his strategies and aesthetics in the context of mainstream modernism and its definitions.

Esherick was a friend of many left-leaning and politically active artists and writers, among them Theodore Dreiser and Sherwood Anderson, both of whom were close friends who drew him into supporting their causes.3 Esherick was also actively engaged in a number of alternative communities: he moved his family to Fairhope, Alabama, in 1919, so his children could attend the School of Organic Education, an alternative school run by reformist Marietta Johnson, who believed children learned through play and experimentation; while living there he taught art at the school run by a nearby African American church, even though he had to hide the fact in the strictly segregated town. The Eshericks spent summers from the 1920s into the mid-1930s at a eurhythmic dance camp in the Adirondacks run by Ruth Doing, and, through Doing, Esherick became involved with the Anthroposophist Threefold Commonwealth Group in New York City. His interest in furniture was spurred by the Expressionist chairs crafted by Fritz Westhoff for the Group’s restaurant as well as by the ideas of Rudolf Steiner, the founder of Anthroposophism, among them the direct influence of design on human thoughts, feelings, and a sense of community, and “organic functionalism.”4 For many years Esherick was also very involved in the Hedgerow Theater in Paoli, which, run by the director Jasper Deeter, had a national reputation for its intelligent production of serious modern drama, and drew important playwrights and actors from New York who participated in the theater’s communal living arrangements. Esherick’s experiences—his decisions to participate in these activities even as he pursued his design career—informed the development of a strong social consciousness and strengthened his instinct for alternative methods and ideas.

Marjorie Content, Wharton Esherick’s Content Bedroom Suite in New York City Apartment, c. 1933. Esherick Family collection. Courtesy rare book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

Esherick’s career traces an unusual arc in its move from fine art to design as he refined his ideas about living environments. He trained at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, and painted in the “Pennsylvania Impressionist” style. Carving wood frames for his own prints and paintings led to wood-cut printmaking, which developed into an extensive corpus of book illustration, and then led to woodcarving.5 Esherick’s first furniture, produced in the late 1920s, emulated the prismatic forms of Cubism and Expressionism, and was predicated on the modernist idea that functional objects did not need decoration. A walnut bedroom suite commissioned by Marjorie Content in 1932 shows Esherick’s growing sophistication, with a semicircular chest of drawers cascading outward from the head of the bed. Esherick produced an increasingly refined series of wood furniture for commissions that mostly came from friends and acquaintances, and he was also hired occasionally as a designer of interiors, including a significant project in 1937 for Curtis Bok, the publishing executive. That project included a graciously large spiral staircase constructed from reclaimed pine beams, and faceted walls in the library that allowed curtains and lighting to be concealed. He began to be known for his design work: the 1939–40 New York World’s Fair included “A Pennsylvania Hill House” with a staircase and furniture designed and constructed by Esherick. The staircase, a massive, Cubist- inspired structure, with cantilevered steps anchored into a carved red-oak tree trunk, had been constructed by Esherick for his own studio, and it was a conceptual breakthrough as well as an engineering feat. Esherick thought that his designs should succeed on their inventive profiles and shapes alone, and in his later projects he demonstrated that his interest lay as much, if not more, in constructing environments than crafting discrete objects.

As he matured, Esherick dropped the references to earlier styles and focused on enhancing the characteristics of his materials, finding movement in the textures of the wood and creating forms that revealed its natural structure, rather than refining and realigning according to an imposed geometry. The early commissioned works that were a focus of the Penn exhibition show an evolution from his first, awkwardly crafted wooden furniture to sophisticated, fluid forms in the integrated environment of the library he designed and built for Bok. These projects—the larger ones almost exclusively commissions from friends—are invariably made of wood, although Esherick would work with metal on rare occasion, usually as some kind of simple decoration. The profiles of his furniture and walls are lined and stepped, and various faces of his structures are integrated with curves or series of angled planes rather than set at right angles. Their organicism was more eccentrically dynamic than that of Arts and Crafts styles; Esherick had by then also absorbed the formalist experimentation of Expressionist architecture. His designs in the thirties and forties were refined, organic but also rigorously modern in their progressively simplified lines and consistent consideration of function.

Edward Quigley, Bok House—View Looking from Library through Carved Oak Doorway into Music Room, 1938. Esherick Family collection. Courtesy Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

The Penn exhibition, with its title “Wharton Esherick and the Birth of the American Modern,” was an attempt to redress a perception of Esherick as a hermit craftsman, disengaged from the modern world. In actuality his historical position is not as simple as the project suggested; his relationship to contemporaneous ideas of the modern, and in particular modern design, is more complicated and contested than the exhibition conveyed. More than the thesis proposed by the show, it was the abundance of materials that stimulated thinking, in particular about the connections between Esherick’s work and the current, cresting wave of interest in mid-century modern design and the collaborative motivations of much recent art and design production.

Although he has been embraced by craft historians, Esherick’s early career shows him thoughtfully engaged with modern design ideas. He identified more with industrial design than as a craftsperson; in fact, many of his early furniture designs were executed not by him but by a local cabinetmaker, John Schmidt.6 Some of Esherick’s projects were constructed of found objects; in the summer of 1938 he used surplus hammer handles to construct chairs for the Hedgerow Theater rehearsal hall. In his interest in function, Esherick connects interestingly with many of the tenets of modern design, particularly with what Museum of Modern Art curator Edgar Kaufmann Jr. termed in 1950 “the good life,” a life that was enhanced by well-designed environments.7 Esherick was very interested in behaviors that could be elicited by designed objects and architecture. He believed in their liberatory possibilities and, with some impetus early in his career from Steiner’s Anthroposophism, that his work would provoke positive and beneficial human responses and foster a connection to others.8

But Esherick was clearly not interested in a modernism that promoted an aesthetic of legible, rational structure, undecorated and uncomplicated white walls, and transparent surfaces. In contrast to dominant ideas about the modern at the time, including spare, geometric lines, manmade synthetics, and machined forms, his aesthetic was determinedly material and sculptural. It is this emphasis that placed him outside the straight-line path of historical modernism and disqualified him from that the ranks of the far better known designers such as the Eameses and the Cranbrook Academy-associated Eliel and Eero Saarinen, Florence Knoll, and Bertoia. In addition to Esherick’s affinity for the elements of craft rather than high design and architecture, his location outside of a large urban center has helped to confine him to regional status and contributed to his reputation as a craftsman rather than a designer. Esherick’s extra-artistic concerns— his artisan/worker’s political awareness and involvements, his preference for alternative communities, his retreat from the city, his interest in spiritual aspects of work—have also marginalized him. It has been easy to dismiss his designs as anti-modern; in fact, Esherick subscribed to all of the values dismissed by Rosalind Krauss as un-modern in an essay she wrote in 1978 dividing craft from art: “too homey, too functional, too archaic.”9

Consuelo Kanaga, Wharton Esherick’s Spiral Stair, ca. 1940. Esherick Family collection. Courtesy Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

All histories simplify in their development of coherent summaries; recently, with the work of historians such as Edward Cooke, Glenn Adamson, and others, the narratives of modern design and craft are becoming more complex and more expansive.10 In an increasingly capacious account of mid-century design, Esherick’s early works might be seen as providing an alternative to mainstream modern—still modern, perhaps a forerunner of the sleeker postwar modern of Nakashima and others or, at least, on the basis of his idea of furniture as an ethically grounded humanist production, a kind of eccentric modernist. It would be interesting to align him with the ideas championed by Eliot Noyes and others, who advocated a softer modernism in response to the objectivity and impersonality of machine design following Word War II as well as “organic design,” in which each designed object is conceived as an element in an integrated environment.11 It is also worth considering Esherick’s modernism in light of his objects and his intentions for their effects. Esherick’s carved forms, rather than function as mere decoration, produced meaning—not as a kind of narrative symbolism as in many craft objects, but as a design function, grounding the experience of his work in a consciousness of self-awareness and connectedness. The fluid lines of his works were not intended to be decorative, non-structural elements but meaningful complications of structure. His excess of line and material qualities, rather than a kind of ornament that betrays a naiveté, might be viewed as an accumulation of meaning and value—not supplemental but integral to a unified whole.

Esherick’s interest in and commitment to alternative living arrangements, communal activities, and interdisciplinary creativity that developed out of his early experiences provided a basis for his alternative modernism. His relationships with politically active friends created motivation to be socially engaged; their grappling with contemporary aesthetic issues informed his own attempts to account intellectually for his stylistic decisions. His consideration of Steiner’s philosophy helped to inculcate a sense of responsibility to functional design. In his later years, Esherick remained interested in the meaningfulness of his choices as a designer, ethical as well as aesthetic—in the potential for designed space to motivate behavior, in the value generated by functionality, and in handwork and the authenticity it generated. These more social aspects of his work connect him in ways that are compelling to the current prominence of design that is socially responsible, historically aware, and handmade, as well as to the systems of exchange and communal support that characterize much contemporary DIY production—concerns that provide interesting backdrop for reconsideration of Esherick’s career and a more nuanced investigation of what it meant to be modern.

Scene from When We Dead Awake, stage set by Wharton Esherick, 1930. Esherick Family collection. Courtesy Rare Book and Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania.

In these ways, the exhibition, although it did not explicitly link Esherick’s practice to architectural or art theories about modernism, provoked a rethinking of the complex and multiple intersections of design, craft, and art, as well as a reconsideration of the ways in which modernism has been defined from the mid-twentieth century until now. To account for the ways in which practices parallel to mainstream design not only responded to classically defined modern productions, but were encountered by and influenced the mainstream, requires an amplified historical field, one that conduces the discursive effects of alternative practices, and dynamically charges the retrospective process of history construction. In responding to Esherick from our perspective, his socially motivated and crafted design sensibility seems more relevant, more central to a generative view of modernism—a view that also more powerfully animates the present.

Sheryl Conkelton is a curator and art historian living in Philadelphia. She teaches at Moore College of Art and Design.