To dispense with the straightforward biographical information: Sherrie Levine was born in 1947 and grew up outside Saint Louis. A baby boomer from the American suburban 1950s with its nativist patriotism and ugly racial politics—she recalls the films of that dark bourgeois ironist Douglas Sirk as a serious distraction in those years1—she enrolled at the University of Wisconsin in 1965 and was there (BA, 1969; MFA, 1973) during the heyday of anti-Vietnam War actions on campus, reading Herbert Marcuse and Franz Fanon (and no doubt Jorge Luis Borges), steeping herself in French and German New Wave cinema, and encountering project-oriented artistic practice through visiting California conceptualist Stephen Kaltenbach. Originally trained as a painter and printmaker, her early work was in collage, and some of these were included by curator-critic Douglas Crimp in a now-famous 1977 exhibition, Pictures. Around 1980, she began rephotographing photographs by canonical Modernist photographers and in 1981 she had her first (and only) one-person show at Metro Pictures, in which she exhibited twentytwo images from her photographic series, “Untitled, After Walker Evans,” presenting beautifully printed photographs of reproductions of photographs taken by Evans for the FSA. The show was a scandal and success in the New York art scene; Levine’s rephotographic projects were rapidly assimilated by critics as key emblems for the “Pictures Generation,” a loose-knit group of artists working both materially and theoretically with reprographic techniques and best identified with Crimp’s 1977 show and his two essays of the same name, and with his colleagues at the journal October. As Levine would put it in a 1986 interview, “At the time, my support systems were critical rather than financial. October was the earliest of these systems.”2 Ensuing decades have seen her practice materially broaden to take up the technique of casting, which she has done in base and precious metals and in glass, as well as painting, printing, and papermaking, and the contemporary genre of installation. If the techniques remain essentially reprographic, the consistent through-line is the exploration of the economies established by the “retinal” (as Marcel Duchamp put it) and its “non-retinal” supplements. In November of 2011, the Whitney Museum of American Art mounted Mayhem: Sherrie Levine, a major career retrospective presenting over three decades of work.

Sherrie Levine, Avant Garde and Kitsch, 2002. Cast crystal: 7 × 2 × 1 ¾ inches and cast bronze: 7 ½ × 2 ½ × 2 inches. Edition of 12. © Sherrie Levine. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

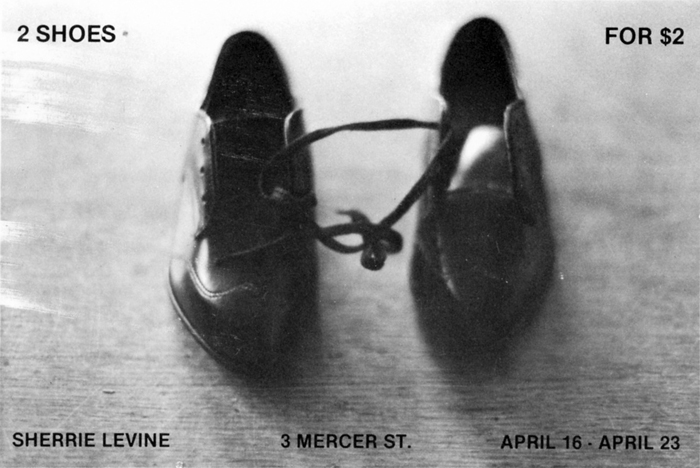

Levine’s first solo show in New York took place in the same year as Pictures. The exhibition—Two Shoes for Two Dollars— presented (and sold) seventy-five pairs of boys’ dress shoes. The strategy was Duchampian updated by sales receipts. Levine had found the shoes in a Bay Area thrift store in the early seventies and had carried them with her to New York.

In 1977, she recalls, the director of the 3 Mercer Street Store had been “looking for artists who wanted to show things… that weren’t the kind of thing you find in a gallery, but which made reference to the store…. [W]e did a show that took place on two weekends…. Two shoes sold for two dollars, and they sold out immediately.”3 The obvious critical route in was via the concept of the fetish, both in the Freudian and in the Marxian sense, but the loaded content and seriality of these miniature bluchers also suggested the expansion of these two reference points via a third trope, that of fractured or only obliquely apprehended narrative. “Seeing all those shoes spread out on a table, one inevitably wished to animate them, to invent stories in which they became the synecdochic characters,” Crimp would write in his essay for Pictures.4 The critic’s discussion marked out an epistemological shift that he had not yet named but which, by the time the catalog essay was revised for the pages of October, he had identified as “Postmodernism.” In this second “Pictures” essay, Crimp elaborated on the implications of the peculiar melancholia of which Levine’s shoes were symptomatic: “If it had been characteristic of the formal descriptions of modernist art that they were topographical, that they mapped the surfaces of artworks in order to determine their structures, then it has now become necessary to think of description as a stratigraphic activity,” one addressed to “processes of quotation, excerptation, framing, and staging that constitute the strategies” of contemporary work.5

Postcard announcement for Sherrie Levine’s Two Shoes for Two Dollars, 3 Mercer Street Gallery, New York, April 16–23, 1977. © Sherrie Levine. Courtesy Thomas Lawson and Susan Morgan.

“Every word, every image, is leased and mortgaged,” Levine writes, in a 1981 artist’s statement. “We know that a picture is but a space in which a variety of images, none of them original, blend and clash. A picture is a tissue of quotations drawn from the innumerable centers of culture…. We can only imitate a gesture that is always anterior, never original.”6 Indeed, the standard interpretation of Levine’s work has subsumed it under the banner of the copy in its property form, appropriation. As such, the work stands as a near-zero-degree statement of picturing or, more generally, re-presentation; and thus, like Duchamp’s readymade, it presents a dead end that is also an intellectual wormhole. In Howard Singerman’s new book, Art History, After Sherrie Levine, Levine is not so much a photographer, collagist, fabricator, or constructor, not so much even an artist in the traditional sense, and perhaps not even an appropriationist, as she is a new kind of art historian, drilling a critical tunnel through aesthetic Modernism while restaging key contemporary art historical discussions (I think in particular of Rosalind Krauss on Duchamp and Constantin Brancusi)7 via complex, allusive material and occasionally linguistic exegeses.

Art History, After Sherrie Levine is both monograph and not. It is “the first in-depth survey of Levine,” the jacket blurb tells us, yet the “after” of the title indicates a temporal and spatial displacement—the book post-dates and stands to the side of the work—while also following in the venerable tradition of the artistic copy, the propaedeutic exercise. His title, of course, takes the form devised by Levine herself (generally, “Untitled, after [name of artist]”); it also, though probably inadvertently, repeats the title (“After Sherrie Levine”) of an artwork by Michael Mandiberg.8 Inasmuch as this formulation repeats Levine’s own, too, the implication is that Singerman’s book presents, à la Levine, a reproduction of reproduction(s) of Levine’s work. This takes us somewhere, for “if this book is in some absolute way not about Sherrie Levine, it is, I guess also absolutely, about me.”9 Singerman received an MFA in 1978 from the Claremont Graduate School. He worked as an editor at the Museum of Contemporary Art, in Los Angeles, from 1985 to 1988 before heading off to doctoral study in the Visual Culture program at the University of Rochester, where he earned his PhD in 1996. His groundbreaking 1999 book, Art Subjects: Making Artists in the American University, a study of the professionalization of art and art education in the United States, has become a key text in contemporary discussions of alternative pedagogical models. These slim facts may seem incidental; yet this quick sketch traces out a trajectory through the studio and the museum collection to the place of pedagogy (Singerman is a university professor and an historian of the teaching of studio art) understood as grounded in discursive objects.

Comprising six dense chapters simply yet deceptively titled by medium or strategy—Pictures, Photographs, Paintings, Endgame, Sculptures, and Counting—Singerman’s book takes the work of Sherrie Levine as the complex occasion for rethinking the disciplinary concerns and procedural moves of art history. Or rather, the book proposes Levine’s oeuvre as something more closely resembling a Badiouean event (though Singerman does not deploy this concept), that is, as a paradigmatic constellation that becomes legible through the reflective interpretive act of the subject whom, in some senses, the event has itself called into being. And Singerman has kept the faith since first seeing (and reviewing) Levine’s photographs after Walker Evans in a small Los Angeles gallery in 1983; he has been working on this book, he tells us, for nearly two decades.

Taken as meditations on or unfoldings of the implications of Levine’s oeuvre, the book’s chapters are organized in a chronology that loosely follows a sequential exhibition history. Singerman’s method involves the careful, even surgical rereading of the contemporaneous discourse, pitting one essay against another, or one “school” (primarily, critical theory of the October school) against another (whether the smaller artist-run journals like Real Life and Wedge, glossies such as Flash Art and Art in America, or, less frequently, the studied “midcult” criticism of the mainstream art press), or one moment against another, opening out the complex reception histories not just of Levine’s work and her (self-) positioning but also of those works laid alongside or ensnared by her project of citation. At the same time, Levine’s appropriations, which draw on a range of sources from Gustave Flaubert to Blinky Palermo, afford considerations of touchstone moments in the history of Modernist abstraction. These moves, the published critical assessments as well as the oeuvre itself, Singerman argues, have still not been fully digested. Levine’s work, he writes, “poses questions that are still better answered by ‘interpretation,’ by criticism rather than art history.”10 At issue is the way in which, post-Pictures, Postmodernism was critically constructed in the breach, most prominently by work done in and around the journal October, but also in numerous responsive, reactive texts (articles, artists’ statements, art works) appearing elsewhere in the art world. In a particularly masterful chapter—which is structured by analogies with chess— Singerman borrows Pierre Bourdieu’s field of cultural production to map out that playing field, including what artist Barbara Kruger called its “financial choreographies”11 (though he is perhaps a bit too soft on this aspect), including the corner of it that has developed into the (paraconsistent) academic field of “contemporary art history.”

Sherrie Levine, untitled (Presidential Collage 4), 1979. Collage on paper, 24 × 18 inches. © Sherrie Levine. Courtesy Paula Cooper Gallery, New York.

Singerman’s book follows in a line of obsessional art history texts. Art history has its share of these, of course, and my own pantheon would have to include Alois Riegl’s Stilfragen, which attempted to trace a continuous history of ornamental motifs autonomous from external referents; Aby Warburg’s Images from the Region of the Pueblo Indians of North America, the written version of a lecture on the snake dance (the lecture was delivered in order to demonstrate Warburg’s sanity and win him release from a mental hospital); and George Kubler’s 1962 The Shape of Time, in which Kubler argues for an independent history of forms in which their elements recur across cultures and over time in response to different problems.12 All three of these texts, as it happens, are concerned with style; more pointedly, they are concerned with the distributive signifying capacities of form over time; and more pointedly still, though emerging from the discipline of art history proper, each of these texts has been foundational for the more historically inclined branch of visual cultural studies. Art History, After Sherrie Levine, given its binomial subject of “art history” and “Sherrie Levine,” follows in their wake in its exploration of time and form, here the time and form(s) of Modernism as radically condensed in Levine’s (perversely) singular appropriative oeuvre. The result is an elliptical text, shaped by recursive loops and backtracks, by re-readings and self-reflection.

But the obsessional texts that Singerman’s book brings to mind more directly form a recent genre within art history, one coeval with Levine’s project and with the three decades of Singerman’s fidelity to it. The most recent of these, T. J. Clark’s 2006 The Sight of Death: An Experiment in Art Writing, presents the artful record of one year’s daily contemplation of two paintings by Nicolas Poussin, an account whose journal format—the continual reconsiderations, the returns-withquestions, the blind spots—is juxtaposed with Clark’s typical painstaking material and historical parsing of visual detail and contemporaneous critical literature while threaded through with the author’s reflection on his own, and his mother’s, mortality.13 More proximate to Singerman’s subject matter, Molly Nesbit’s 2000 brilliant and underappreciated Their Common Sense, in which the author addresses Duchamp by his first name, virtually reinhabits that artist’s boyhood schoolroom by way of sorting through the enmeshing of the commodity form, visual abstraction, mechanical drawing, and skilled labor.14

Before any of these, of course—not after Sherrie Levine but before—comes Roland Barthes’s lapidary 1980 meditation on photography, La Chambre Claire, published the following year in English as Camera Lucida, in which the author famously attempted to theorize a subject’s interest in a given photograph via the twined (though not twinned) terms studium and punctum, the former the pedagogical, affirmative tracery of “a kind of general, enthusiastic [cultural] commitment” found by the viewer in the photograph and the latter, strikingly, a psychic wound inflicted on the viewer by some fleeting, deceptively inconsequential detail.15 These two terms seem wholly apt to Singerman’s project in Art History, After Sherrie Levine. For this hugely ambitious text, with its nearly mnemonic detailing of the discourse invoked by the name “Sherrie Levine,” itself has an underlying melancholia: this is implicit in the resistance to historicizing. If Singerman’s masterful retooling of art history in favor of deep, precisionist yet associative reading models long-term commitment to a difficult and evolving oeuvre, in so doing it cannot help but also demonstrate the temporal passage of the very critical constellations it maps out. Aptly, the words in Levine’s 1981 artist’s statement, quoted above, are appropriated, of course, from the conclusion of Roland Barthes’s “The Death of the Author”—the essay in which he famously concludes, “we know that to restore writing its future, we must reverse its myth: the birth of the reader must be ransomed by the death of the Author.”16 And surely the signatory of that artist’s statement has met her ideal reader.

Judith Rodenbeck is the author of Radical Prototypes: Allan Kaprow and the Invention of Happenings. She teaches art history at Sarah Lawrence College.