no symbols where none intended —Samuel Beckett1

Fuck Scott Carpenter

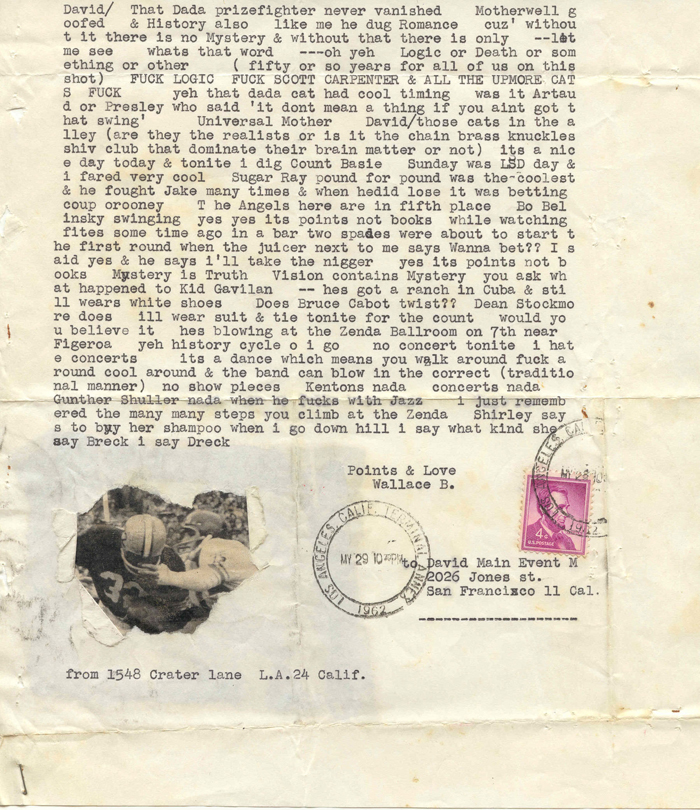

On May 29, 1962, Wallace Berman typed out a short letter to his friend, the poet David Meltzer.2 In inimitable Berman style, the letter is part missive, part collage, part exercise in willful typographic perversity: a perfect example of the ephemeral and social art practice that characterized one important aspect of Berman’s output during a protean yet tragically truncated career.3 As I hope will become clear, it also encapsulates a poignant, angry, petulant, and prophetic meditation on (art) history, the fact of mortality, the fatality of logic, and the specter of a civilization both rationalized and romanticized by science and technology. Although Berman’s work is often described as comprising a kind of “secret code [we’ll return to both of these ideas, ‘code’ and ‘secret,’ presently], a language that may have been most easily understood by his close circle of friends,”4 this particular text, while perhaps not entirely pellucid, does leave considerable room for interpretation.

Wallace Berman, Letter to David Meltzer (football players), 1962. Typed letter with photographic collage, 9 1⁄2 × 7 1⁄2 inches. Collection of Philip Aarons and Shelley Fox Aarons, New York.

Perhaps the easiest “points of entry” are provided by the brutally ad hominem attack, “FUCK SCOTT CARPENTER,” and the inscribed date. As it happens, Berman’s letter to Meltzer was composed just one week after M. Scott Carpenter became the fourth American astronaut to fly in space, his mission in Aurora 7 being the first after John Glenn’s epochal demonstration of America’s “Right Stuff” proved the capacity of NASA to put an astronaut into earth orbit and bring him safely home again.5 But Scott Carpenter was no John Glenn. Widely perceived as the least lockstep of the original Mercury 7 astronauts, he declined to function simply in the role of an engineering test pilot which NASA had blocked out for his mission. Fascinated by the mystery of the glowing “fireflies” observed earlier by Glenn and enraptured by the experience of being in space, Carpenter apparently misjudged the amount of fuel needed for a safe return. He ended up having to pilot his craft manually through re-entry, and overshot his intended landing target by over two hundred miles. In the words of flight director Chris Kraft, Carpenter needed a shot of “uncanny luck,” or he could easily have become America’s first space flight fatality.6

Berman, however, seems not to have perceived Carpenter as any different from “ALL THE [other] UPMORE CATS” like John Glenn, who embodied that most deadening of all rationalistic concepts, “LOGIC.”7 As such, they seem opposed to the shadowy “Dada prizefighter,” with whom Berman opens his letter and who has mysteriously “vanished” in the wake of NASA’s ongoing triumph. But vanished where? Perhaps into that “History,” which like “Motherwell” and Berman himself have somehow “goofed.” (Here Berman’s reference is most likely to Robert Motherwell, editor of the fundamental collection Dada Painters and Poets [first edition 1951], which would have been an important intellectual and art historical resource for Berman and his circle.)

Admittedly, it is difficult to puzzle out Berman’s precise meaning here. It is not at all clear, for example how “History” as a capitalH concept might conspire to “goof” in regard to its own unfolding, although Motherwell and Berman might easily be mistaken in their evaluation of historical events. But it does seem to be the case that, whatever else the equally elusive “UPMORE” might imply, it cannot describe one who, “like me” (Berman) and Motherwell and the Dada prizefighter, has “dug romance.”

Alas, “romance” is itself a notoriously malleable concept, and one that has often been applied to precisely the kind of endeavor exemplified (albeit in different ways) by Carpenter and Glenn. Yet it is a concept that here holds the key to Berman’s meaning, “cuz’ withou/t it there is no Mystery & without that there is only — let/me see whats that word oh yeh Logic or Death or som/ething or other[.]”

So “FUCK LOGIC” and in doing so deny death, which is itself a matter of some urgency since for each of us, Berman adds parenthetically and presciently, there are only “fifty or so years…on this shot.” And what better way to do that than by becoming a kind of anti-Scott Carpenter for whom romance and rationality—Logic and Mystery— are forever sundered, although ironically enough, Carpenter himself seems to have had his death-denying “other” already inbuilt. In a sense, I would argue, this letter succinctly, if at times ambiguously, sums up Berman’s basic artistic program. This is not to say, however, that it provides some kind of skeleton key capable of unlocking Berman’s meanings across an entire career. Indeed, one of the central issues raised by Berman’s work involves the very question of meaning’s possibility in a world where both romance and rationality are inextricably intertwined in the service of a dominant ideology (for which NASA can perhaps serve here as a convenient metaphor). And the answer to that question, in turn, has profound implications for the process, the potentialities, and the limitations of interpretation. It is to those questions (and their answers, I hope) that we now turn.

Speaking in Tongues

The basic issues involved here have been clearly laid out by the relevant curators and essayists involved in the Getty Research Institute’s brilliantly encyclopedic set of exhibitions, Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945—1980. Especially trenchant were the essays that accompanied the exhibition Speaking in Tongues, a dual re-evaluation of the work of Berman and the “photographist” Robert Heinecken mounted at the Armory Center for the Arts in Pasadena.8 Nor is it my intention to challenge the basic insights articulated in this substantial body of scholarly work. Rather, I want to examine a few points in somewhat more detail, and perhaps from a somewhat different perspective, both to enhance our understanding of Berman’s work, and to explore some of the ways in which both that work and the discourse around it can bring into focus some issues of more general importance to the enterprise of interpretation.

What better place to begin than with the title to the Pasadena Armory show? Speaking in tongues—technically referred to as “glossolalia”—brings to mind a practice associated with American Pentecostal Christianity.9 It denotes a state of possession by the Holy Spirit, in which the believer speaks, shouts, prays, even sings in an unknown “language.”10 Although such utterances can be seen as having prophetic force, they are fundamentally understood as comprising gifts of the Holy Spirit, enactments of a divine response to intensity of faith in the living Word. As such, they are clearly related to the kind of physically encoded and equally ecstatic gifts made manifest by Catholic saints like Francis of Assisi and Teresa of Avila.

They are also extremely difficult to interpret. They are what they are, or, perhaps better, they say what they say. But as to what, exactly, that being or saying might mean, that is a rather different matter, since what they testify to is a specific state of being, rather than a particular doctrine or theological argument. One speaks the Word, which is God (John 1:1) and hence transcendent and unknowable.

In the beginning, however, the phrase “speaking in tongues” referred to quite a different kind of gift that was bestowed on the disciples by God on what became the Feast of Pentecost (Acts 2:1–13). At that moment, as tongues of fire danced over their heads amidst the sound of a great rushing wind, the disciples were miraculously granted the ability to speak so that each man present (Parthians, Medes, Elamites, Mesopotamians, Judeans, etc.) heard them speaking “in his own [native] language” (v.6) despite the fact that “all these who are speaking [are] Galileans” (v.7). This is quite the opposite of the phenomenon described above. This “speaking in tongues” is not something transcendent and unknowable, but something quite practical—the ability to speak so that every listener can hear the Word of God and understand. The language(s) spoken by the disciples are transparent to the message they seek to convey; so that, in a sense, translation (read: “interpretation”) becomes almost unnecessary—“almost” because, in whatever language it is spoken, God’s word is never merely transparent. We can see this distinction operative, for example, in two of Berman’s more “traditional” collages, the passionate yet delicate Untitled (Lenny Bruce), 1963, and the beautiful and evocative “signature” piece, Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag.11 In the former, the iconography, though not strictly “kosher” by art historical standards, still allows us to read the image easily as an homage to the pivotal performer of cultural revolt, seen “as a beaten-down Poet Laureate crowned with a wreath of dried leaves and butterfly wings.”12 At the same time, Albert Goldman’s brilliant description of Bruce as “an oral jazzman” in performance, reproduced here from the more extensive quote given in Claudia Bohn-Spector’s essay in Speaking in Tongues, might as easily apply to much of Berman’s own art practice: “Sending, sending, sending, he would finally reach a point of clairvoyance [speaking now in American Pentecostal tongues] where he was no longer a performer but rather a medium transmitting messages that came to him from out there— from recall, fantasy, prophecy.”13

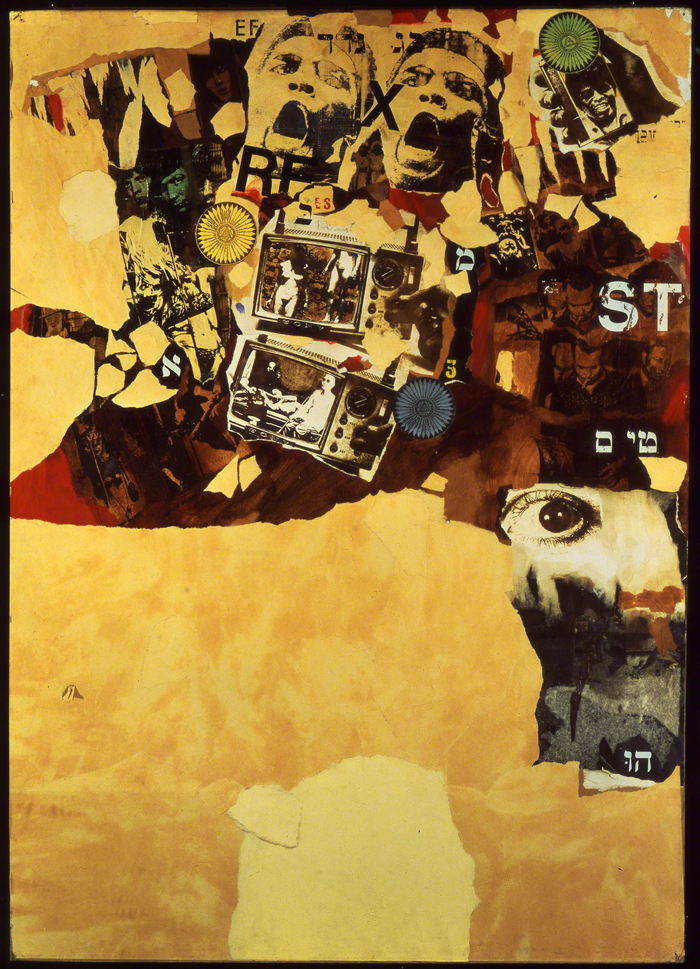

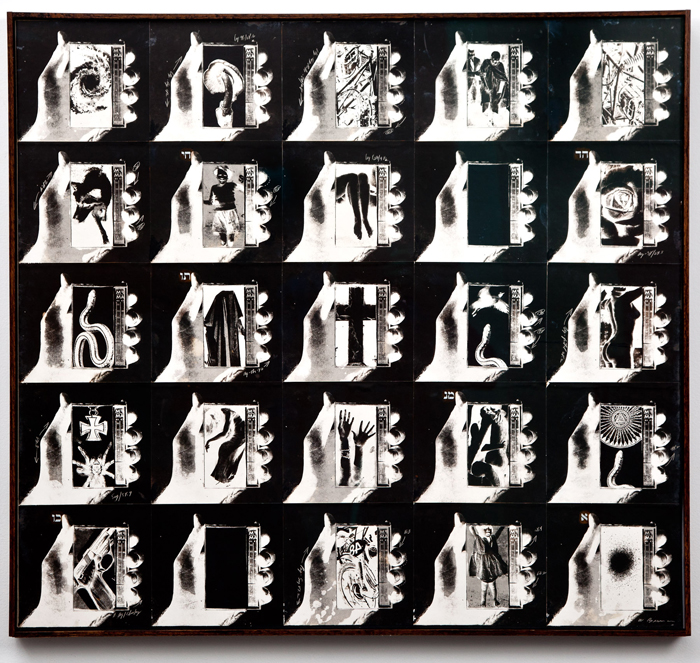

Wallace Berman, Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag, 1964. Mixed-media collage, 44 1⁄2 × 32 1⁄2 × 2 inches. Collection of David Yorkin and Alix Madigan, Los Angeles. Courtesy the estate of Wallace Berman and Michael Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles.

This is much more the effect that one gets from Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag, where the imagery is “louder,” more aggressive, almost incantatory in its use of repetition,14 and where the identity of the figures and events (with the exception of James Brown himself at the upper right) seems to hang maddeningly just on the edge of consciousness.15 The moment of interpretation is here encapsulated more as a struggle for meaning, which can almost, but maybe never quite, be won. Or, as David Meltzer writes retrospectively in his poignant memorial poem “Doom Cusp:”16

Am in the ozone no zone liminal fat w/past bogged down in tense present

[…]

detoured to there where nobody’s here u nless they’re dead

almost there

Indeed, Berman’s collage even seems to underline the importance of that final “almost,” especially in the doubling up of not-quiteidentical images in close proximity, as though they were being observed through an apparatus intended to bring them into a sharper focus as yet unachieved. At the same time, that same doubling draws our attention forcefully to the degradations inherent in processes of production and reproduction; and in the case of the two primitive portable televisions, which display quite different pictures, to the idea that differences of this type (even those that degrade a “pristine” original) can in juxtaposition increase information, magnify resonance, and (perhaps) facilitate interpretation.

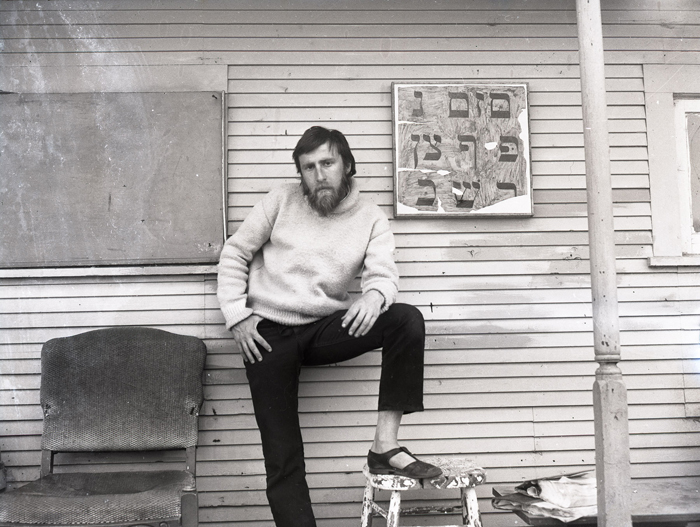

Unknown photographer, Wallace Berman at Larkspur, 1958. Gelatin silver print. No dimensions given. Courtesy Estate of Wallace Berman and Michael Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles.

Sending in Code

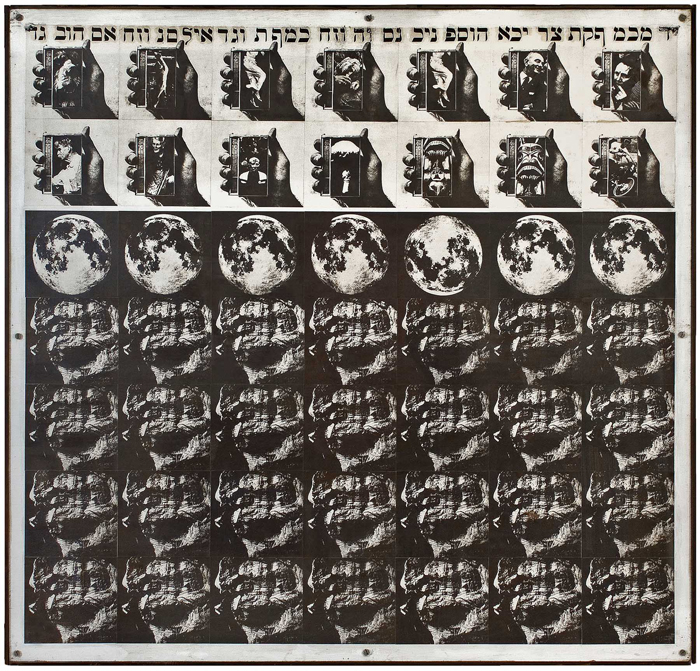

“Code” is probably the single most commonly used word in discussions of Wallace Berman’s art practice. It certainly permeates the analysis in the Speaking in Tongues catalog. And it seems completely apropos. One has only to look at one of the fifty-sixunit Verifax collages, with the relentlessly repeated handheld radio “broadcasting” a sequence of allusive images embedded in a mysterious syntactical structure, to imagine oneself looking at some kind of coded transmission. Perhaps we see the visual equivalent of David Meltzer’s “scriptic dance conveying/ all the possible poses of mystery”17 in the juxtaposition of common scenes and objects defamiliarized and made somehow ominous in the process of their appropriation and reiterated reproduction.

We will return to the issues raised by this kind of transmission shortly. But first, it might be well to remember that the word “code” carries at least three distinct connotations, all of which are more or less relevant in the present circumstance. In the first and almost trivial instance, the word can refer to a code of behavior, a way of being and doing. In Berman’s case, this would be a code that inter alia grew out of “an involvement with the world of jazz, which was the culture of hipsterism.”18 In many ways, this code of the “cool” and the “laid back” hardly serves at all to separate Berman from the larger cultural milieu within which he moved and worked; indeed, it defines that milieu in general rather than Berman’s particular space within it.19 That particular, personal space, within which coded behavior allowed Berman to fashion a distinctive self, was the space of the quiet yet charismatic “outsider” at the very center of things, the self-styled “Yiddish Indian,”20 who “would never talk about…his art and his creative process…. By his code, this would be very uncool.”21

Secondly, the word “code” can define a set of cultural relationships and meanings which are both inherent in our lived culture and capable of conscious manipulation within that culture—meanings are “encoded” into objects and their relationships via conscious or unconscious processes of cultural production, and can be “decoded” (that is, made manifest and available for critique) by means of a set of analytical procedures associated with the discipline of semiotics, as well as through particular strategies of artistic practice. In this sense, the idea of a “code” is often associated with the work of Roland Barthes.22

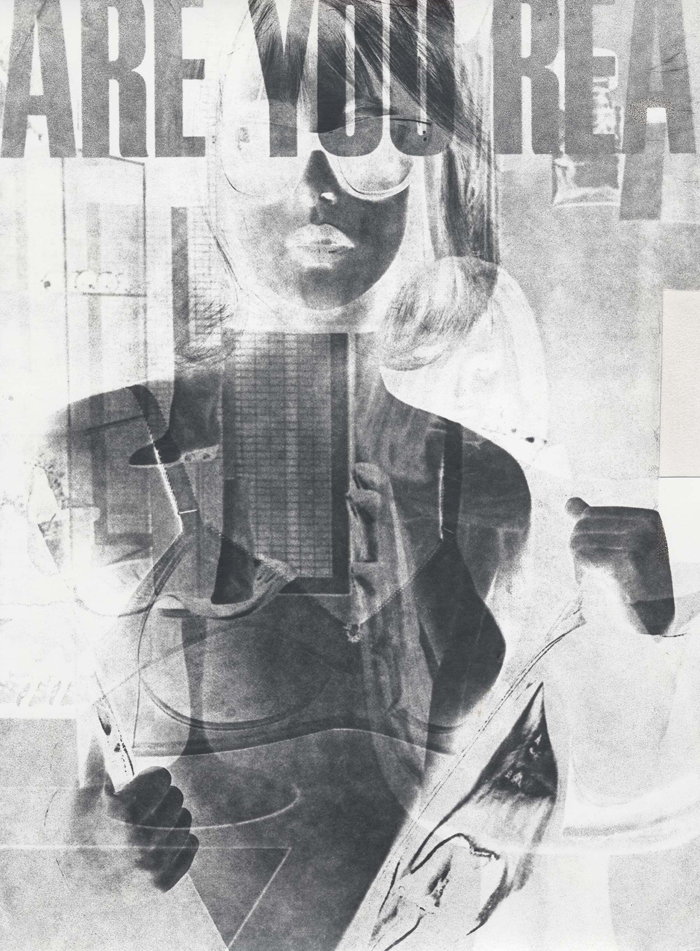

Although the previous paragraph’s discussion is nothing if not a gross over-simplification, it is nevertheless useful insofar as it draws our attention to the following: that one line of critical art practice during the period that spans Berman’s career was explicitly or implicitly concerned with the “decoding” of popular culture, that is, with laying bare the ways in which that culture articulated an ideology in which images of sex, power, greed, amoral professional advancement, violence, brutality, etc. lay always just below the surface of a life that appeared as deservedly happy, wealthy, fulfilled, serene, and at peace in its own self-realization. As the catalog of the exhibition Speaking in Tongues makes clear, Robert Heinecken was a master at this kind of decoding, perfecting a working practice, for example in the portfolio Are You Rea (1964–68) that revealed the tensions and dislocations “hidden in plain sight” in the popular media.23 And his later magazine interventions and reconfigurations, although perhaps less brilliant in technical strategy, often perform a similar and politically motivated decoding function, sometimes to great effect, as in the Untitled (n.d.) work captioned “This is the way love is in 1970,” which disfigures the iconic beauty of Ali McGraw with Heinecken’s “signature” appropriation—a photograph of a grinning Cambodian soldier holding the decapitated heads of two Viet Cong soldiers, one in either hand.24

Robert Heinecken, Are You Rea, title sheet, 1967. Offset lithograph, 8.7 × 6.3 inches. Center for Creative Photography University of Arizona.

In my opinion, Berman’s forays in this direction, with the exception of the 1964 Untitled (Office Management) are less successful. The Untitled (salesman) of circa 1965, for example, appears now as dated as the images that the artist has composited. Rather, Berman’s strength lies in the opposite direction, not as a code-breaker but as a code-maker, an originator of secret languages that articulate hidden meanings in a process that does not de-mythologize the mundane, the popular, the everyday, but instead sacralizes or sanctifies it. With this turn we come to the third sense in which the word “code” can be invoked in relation to Berman’s art practice. In invoking it himself, as he most certainly does, Berman sets himself to a practice that is dangerous both in its working out and in its unraveling, since the endpoint here is just as easily opacity as it is transparency. The potential reward of this strategy is a transcendent opening up of meaning, but the potential price is a hermetic sterility. Let us look briefly first at that price.

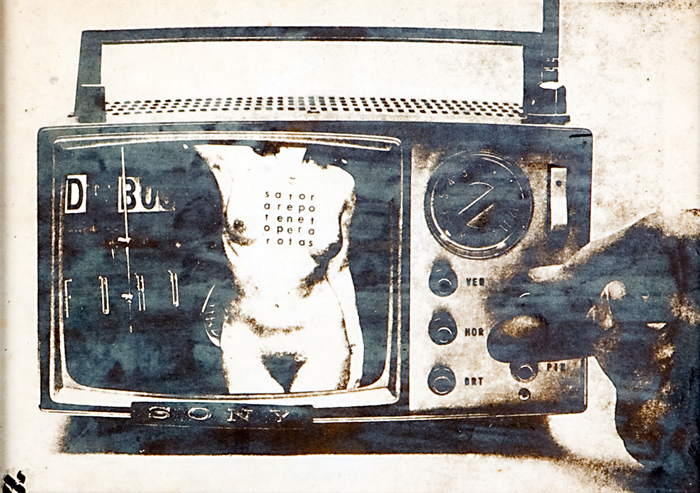

Wallace Berman, Untitled, 1964. Verifax collage, 7.1 × 9.4 inches. Collection of Loïc Malle, Paris.

Sator Square

In 1964, Wallace Berman produced a simple Verifax collage: a single oblong panel framing a similarly shaped and ultra-primitive Sony portable TV; a hand reaches in from out of frame to the right, adjusting one of the set’s controls. Against a murky background where we can discern the word FORD as if crafted in spindly chrome, the picture tube reveals the naked torso of a headless woman. We see her body from shoulders to pubic triangle, thin with a tight waist and breasts asymmetrically arranged, since her right arm stretches up and out of the frame while her left hangs resting at her side. As if printed on her chest between the breasts is a text: a five-by-five grid of letters that spells out the famous palindrome “satorarepo tenet opera rotas” as if it were a numerical “magic square,” reading left to right and top to bottom, right to left and bottom to top, as well as top to bottom and left to right, bottom to top and right to left.

The sator square has its origin in Roman antiquity; it is first attested in the ruins of Pompeii, buried in the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79, and has been found at Roman sites as far distant as Corinium (Cirencester in modern England) and DuraEuropos (an archaeological site in modern Syria). Despite its wide circulation and brilliant formal integrity—try constructing such a square in English—it remains in many ways mysterious. Its cultural origin and original context are unknown, although it is often massumed to be of Christian derivation and has been ingeniously interpreted on that assumption. One of its five words, arepo, is attested nowhere else in extant Latin literature and is of uncertain meaning, to say the least. It has been seen as ecclesiastical in nature and has reportedly been appropriated for magical use. All that being the case, what is it doing on the naked chest of a woman in Wallace Berman’s funky world of Verifaxed mass media?

Wallace Berman, Untitled, c. 1968. Verifax collage, 49 × 46 inches. Collection of Shirley Berman.

It comes to us as some message from an alien world, in this case the world of the past. But what does it mean? Does it constitute a code? And if so, what is the key that unlocks its meaning? As a first approximation, we can make the simple assertion that what the square “means” is nothing more or less than what it “is”: a complex five-by-five grid of letters that spells out a clever four-fold palindrome in Latin. Importantly, both this being and this meaning are literally circumscribed by the outermost frame of letters. The sator square is utterly self-referential and hermetically sealed; it cannot be used to generate more information or to articulate relationships external to itself. Hence, it cannot be used to leverage an interpretation, and in that sense it is meaningless.25 It seems to hover in front of the woman’s naked body, yet it tells us nothing about her, nor does she illuminate it. It remains impotent in its perfection, as she is impotent in her fragmentation, incomplete even as an object of desire. If the sator square is indeed a code, or if it is intended to appear as a code in the context of Berman’s practice, it is a code without a key, and as such perfectly useless.

And this, I would argue, is an image of the potential price to be paid, the wager that Berman (an inveterate gambler and a hustler at heart) must cover to remain a player in a very high stakes game, in which the artist fashions a private archive of images into a code both intelligible and meaningful.26 This cannot be a code for which we are given an explicit key (despite the fact that codes are by definition at some level just such systems of equivalence), but rather one which nevertheless in some way makes its meaning available for interpretation.

Wallace Berman, Untitled, c. 1968. Verifax collage, 49 × 46 inches. Collection of Shirley Berman.

Transistor Radio

The game board employed by Berman, at its most expansive and complex, consists of the fifty-six square grid depicting handheld transistor radios that comprise his most ambitious Verifax collages. These works are enormously impressive, engaging both the images and the instruments of the mass media in a sophisticated structure that speaks to the concerns of Minimalism as much as to those of Pop, all done using an obsolete means of mechanical reproduction that imparts through its very mechanism a handmade artisanal feel, one that resonates with the “vibe” of California assemblage more than that of Andy Warhol’s New York Factory.27 In a sense, Berman’s collages might be the work of an archivist laboring alongside George Herms’s extraordinary Librarian of 1960.28

At the heart of these assembled collages lies the image of the portable transistor radio, a little device that was revolutionizing the dissemination of American popular culture at exactly the same time that the Verifax copier was itself being replaced as an outmoded reproductive technology.29 Berman’s use of it as a framing device for the dissemination of images rather than news or music is arguably brilliant, since it apparently allows the artist himself to intrude at every moment into that process of dissemination.30 Even if the images themselves are recycled or appropriated, their arrangement, their “encoding,” is the province of the creative intelligence (the hand) that controls their relationships at every stage of his message’s unfolding. Duchamp notwithstanding, we are in the presence here of a controlled act of composition, not the operation of random forces. It is not so much that we are intended to “talk to the hand,” as it is that we should see the hand as in some sense speaking to us. In any case, it is the hand of the artist that controls the transmission (not unlike the Control Voice that introduced the TV science fiction masterpiece, The Outer Limits [1963–65] or, for that matter, the voice of God) and that, in theory, guarantees its coherence and meaning.

This does not necessarily make the messages any easier to decipher; nor should it; nor, undoubtedly, was it meant to. As any even superficial survey of their intellectual circle makes abundantly clear, Berman and his friends were steeped in a literary and artistic tradition stretching back to French symbolism that placed a premium on a sometimes scintillatingly corrosive, sometimes violently abusive confrontation with linguistic and pictorial convention.31 At times, this confrontation was focused through a more or less political lens that saw existing conventions as a set of hegemonic constraints imposed on those who, like Berman and his comrades, “dug romance.” At others, it was as if the structure of language and meaning tout court were but servants of “Logic or Death,” to be utterly overthrown in pursuit of some higher “Mystery.” For us, then, the immediate question becomes, where along this spectrum of revolt do the Verifax collages fall? Do they speak in biblical (that is, apostolic and transparent) or American Pentecostal (that is, apocalyptic and opaque) tongues? Perhaps in both, and neither. For sure, they are not transparent, giving up their meanings as if seen through a polished plate of glass. Nor, however, are they opaque, impenetrable, meaningless. Rather, seen from the perspective of an age steeped in digital media, awash in images configured and reconfigured in endless (re)juxtapositions, they appear oddly “primitive” yet familiar, distant yet insistent, like messages left on the wall of a cave, difficult to make out, yet capable of yielding up a plenitude of meaning.

At the opening of his beautifully reflective poem, “When I Was a Poet,” David Meltzer probably does a better job than I of capturing what I’m trying to get at here, which is a sense both of the artist’s infinite grasp and of the infinite craft his hand must exercise in order to produce the pictures (a code of reiterated elements infinitely complex in its simplicity—like the DNA of an entire culture) that we can only “read” through the exercise of an equally infinite patience:

When I was a poet I had no doubt knew the Ins & Outs of All & Everything lettered in-worded each syllable seed stuck to a letter formed a word a world 32

Topanga Canyon Talmud

You look back where once fearful shadows stalked and see the sea, a shadow in the mind, move beneath moonlight. Letters, number, codes lead to nothing.33

The revolt of Berman and his circle, like that of the Beats with whom they were complexly entangled, like that of all those who “dug romance,” was both a search and destroy operation and a quest: an attempt to find another, better, more cosmic meaning, an attempt to penetrate that one great “Mystery” that lay embedded equally in the heart of the human heart (“heart central,” as David Meltzer called it34) and in the heart of the cosmos. This search for alternative ways of seeing, knowing, and being led in many directions, into the (literal) wilderness, psychopharmacology and exuberant sexuality, Jungian psychology and kundalini yoga, Zen and various other esoteric Buddhisms, the I Ching, native American myth, Jewish mysticism, Christian gnosticism, the private epiphanies of the insane, the junkies, the winos, the derelicts, and all along the endlessly twisting and turning flights of jazz, wailing now in inconsolable grief, now in absolute exultation. It produced at least one genuine Zen master (the poet Philip Whalen35) and a generation of “best minds” left “destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,” in the unforgettable opening lament of Allen Ginsberg’s “Howl.” It also had a profound impact on the art practice of Wallace Berman.

Although Berman’s art touches many of the paths noted above, his art is among those most closely associated with the strain of Jewish mysticism embodied in the discipline of Kaballah. With all of the fuss recently generated by the Kaballah Centre of Los Angeles and its stable of celebrity supporters,36 it is easy to forget that Kaballah is a discipline (not a New Age fad) with a deep and profoundly mystical tradition.37 Kaballah privileges the power that it recognizes as inherent in the literal “presence” of the Hebrew language and its alphabet, rather than privileging the meaning of a particular text. Apparently, Berman wants us to believe that he is no New Age fellow traveler. His use of Hebrew letters and soi-disant Hebrew phrases appears as strategic and thoughtful as any aspect of his practice. And his assumption of the Aleph (the first letter of the Hebrew alphabet) as a kind of personal tag bespeaks a real commitment…but a commitment to what exactly?38

As Berman in fact knew no Hebrew, his Hebrew “texts,” and especially his works in which such texts are essentially the only formal elements, present something of a hermeneutic problem. As potential codes, they are more opaque even than the sator square: literally meaningless as given, and clearly beyond the application of any potential translational or transformational operation that might conceivably generate some meaning. It is hard even to call them self-referential.39

And yet, as something simply “being there” they are hardly negligible. Although in a way that might be difficult to specify, they carry “weight,” and in that weight we might discern a kind of meaning. Or if not meaning in the traditional sense, then perhaps a kind of “being there” that is at once also a “being significant.” We might make this argument, for example, with respect to Berman’s beautifully delicate papyrus paintings, where short sequences of relatively large Hebrew characters have been carefully inscribed on a prepared and pre-degraded ground.40 Although the “texts” are meaningless in and of themselves, it is precisely in their being bound to this ground that they acquire an almost archival resonance—of great antiquity (as the Dead Sea scrolls), of fragility and decay, perhaps even of the apocalyptic violence of the Holocaust. And if we remember the old idea that pre-lapsarian Hebrew was a perfectly transparent language (used by Adam to name each in their proper essence the birds of the air and the beasts of the field), we might even see in the papyrus paintings that now-opaque and meaningless tongue miraculously caught by the artist even in the act of degrading toward meaning.

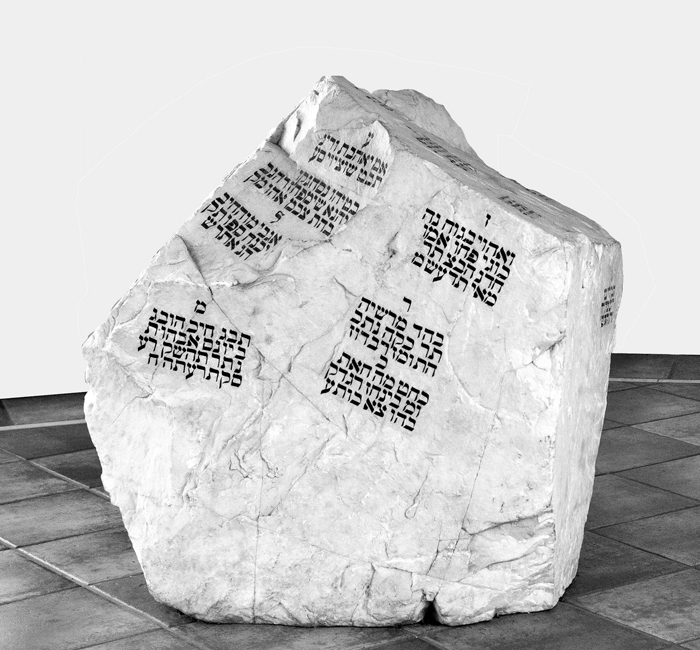

In a similar attempt to account for the generation of meaning through the reciprocal interaction of text and ground, we can look, for example, at the wonderful Topanga Seed of 1969–70. The seed itself is a large chunk of hard and heavy dolomite rock of pleasing shape: neither too sharp in its angles nor too rounded in its curves, solid and well grounded. On it have been arranged blocks of quasi-Hebrew text, most of them identified with a single marking letter that might indicate a sequence. The blocks of text on the “front” are arranged roughly in two columns, perhaps a glancing reference to the traditional organization of the Tablets of the Law, but there are blocks of text also on the other faces of “the seed.” Unlike the sator square in the Verifax collage discussed above, the text here adheres to the surface of the rock, as though the mysterious power of literate culture channeling the divine speaking of the Logos has been grafted indissolubly to the bedrock of the Earth itself, which now becomes the seed of a new knowing that embraces the whole world, the whole cosmos. Or it may be that the Earth itself speaks, again in a tongue unknown and unknowable, a final Talmudic commentary on a text that has the power to unravel Logic and defy Death.

Wallace Berman, Topanga Seed, 1969–70. Dolomite rock and transfer letters. Courtesy of the Getty Research Institute. Courtesy The Grinstein Family. Photo by John Kiffe.

Desolate Angel

As is only right, fitting, and proper, Berman himself has not left hints enough outside his work to give the game of the work away.

Nor is it possible here to disentangle all of the strands of that work, which is more wide-ranging than either I or the Armory curators and catalog writers have been able to suggest.41 What I can do, however, is to end with a final comparison, one that sets Berman into a historical context broader than any that has been suggested up to now.

Rembrandt van Rijn, Old Woman Reading, 1631. Oil on panel; 23 1⁄2 × 19 inches. Collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.

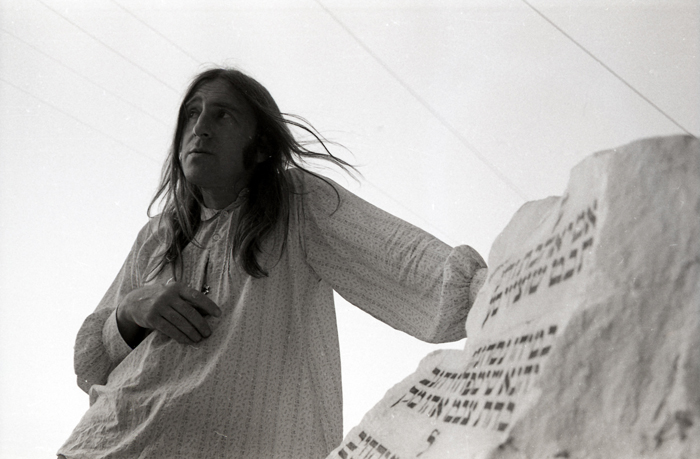

Wallace Berman, Untitled (rocks at Point Mugu with Hebrew Letters), early 1970s. Gelatin silver print. Courtesy Estate of Wallace Berman and Michael Kohn Gallery, Los Angeles.

In the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam is a relatively small painting by the young Rembrandt (monogrammed and dated 1631) that depicts an old woman reading what appears to be a book of scripture. She is dressed in quasi-biblical garb and is often identified as the prophetess Hannah, who recognized the infant Christ in the temple at Jerusalem (Luke 2:36–38). In Rembrandt’s picture, however, it is the book which engages her whole attention: a book bathed in light and written in the same kind of crypto-Hebrew that Berman employed so often in his work. Not only does she bend forward slightly and even seem to have her lips parted as though enunciating the text aloud, she seems literally to caress one of the open pages with her wrinkled right hand as if it were not just the words of the text as meaningful discourse, but the physical presence of the words themselves holding her attention. Clearly, the words are for her a source of power, not just by virtue of what they say, but also by virtue of what they are, physical tokens of the power that speaks them in the language most fit for divine discourse and the revelation of divine mysteries.

Compare this to a photo of Berman from the early 1970s, Untitled (rocks at Point Mugu with Hebrew Letters). Unlike Rembrandt’s old woman, Berman strikes a pose of almost supreme and bemused detachment. His left hand rests on the depicted rock, as if presenting it to a presumed audience. His right hand rests lightly across his chest in a limply theatrical gesture. He looks up, his eyes following the almost invisible power lines into the sky (could it be heaven?). His brows are slightly knit, his expression almost quizzical, as if he waits for the answer to some question. With his long thin hair and his loose shirt, he might almost pass for an angel sent to earth on some mysterious mission. Although clearly placed in relation to an unseen audience, to whom he might be intending to reveal the meaning of the words of power graven on the stone at his side, he seems alone, in a world of his own. While Rembrandt’s old woman struggles to master the text, to grasp its meaning, Berman seems unconcerned with such trivialities. Does he in fact know the secret contained in the pure code of the meaningless text? Will he reveal that secret to us? Will he unlock the mystery of its power? As he strikes his pose in the photo, he proffers none of the answers that we seek. And why should he? He has given us the rock, the text, the work; and it is now for us to seek out the rest. To give anything more would be…uncool.

Glenn Harcourt received a PhD in the history of art from the University of California, Berkeley. He currently lives and works in Los Angeles.