The first space I entered, in the opening section of the 2011 Istanbul Biennial, presented work from the late 1970s by Geta Bratescu, a Romanian woman artist born in 1926. She took old, threadbare fabrics, some patterned, some plain, and patched them together into small irregular shapes, maybe twelve by eight inches or so. Some of the fabrics were enticing in their colors and patterns, some simply worn to a shred. I was reminded of my friend’s New England rhyme: “use it up / wear it out / make do / do without!” The pieces referred to traditional patchwork, in which scraps of leftover clothing and other materials are revived in new patterns and combinations, although this version of patchwork was emphatically nonfunctional. They also covertly referred to a modernist grid, that disembodied system that allows for nonsequential, nonhierarchical arrangements. They spoke of history: a lived history, in which such scraps of stuff were preserved, the remains of a torn dress, a scarf, a slip, and also art history, where, in part through the interventions of women artists, the body returns to haunt the grid, as the repressed always will.

Geta Bra ̆tescu, Vestigii, 1978. textile collage on paper, 13.78 x 19.7 inches. Courtesy the Artist. Teixeira De Freitas collection.

The collages juxtaposed faded mattress ticking, grey-white ribbed cotton knit that could have once been an undershirt, and moth-eaten corduroy, and used the textured ridges and woven stripes of the fabrics to propose a set of spatial relationships, mapping a visual topography, less a bird’s eye view, more like the arbitrary framing of a view from a window, in (I imagine) a city like Bucharest, in the 1970s, a place that was also worn out and haunted by memories. Layered over more dense fabrics, the artist placed tiny scraps of patterned silk: 1930s flowers in deep pink and blue, ancient paisley in orange and beige. The frayed edges of narrow strips of translucent silk chiffon were tenderly laid over the textured cottons and velveteen, producing a transvaluation of values, in which these shreds of stuff, almost trash, become beautiful, evocative of other places and times. The title is Vestigii, a Romanian word meaning remains or traces. In the brief interview printed in the exhibition guide, Bratescu said, “I inherited from my mother a bag of old pieces of textiles from the seamstress who worked in our house when I was a child. The variety of the colors and the warm softness fascinated me.”

Untitled (12th Istanbul Biennial) was divided into five sections, each consisting of a cluster of solo shows and one large room presenting a group show. The fifty-four solo shows extended and elaborated on the themes of each group show, and the work of some solo artists also appeared in the group shows, sometimes in different sections, making connections across the whole exhibition. The five sections were loosely themed around five works by Felix Gonzalez-Torres (Cuba/United States, 1957–1996), works not presented in the exhibition except as small black-and-white reproductions in the accompanying printed guide. These five sections were presented in a loose sequence: Untitled (Abstraction) on the ground floor of the vast warehouse building Antrepo 5, “Untitled” (Ross) and “Untitled” (Passport) side by side upstairs, and across the way in Antrepo 3, Untitled (History) and “Untitled” (Death by Gun), again side by side, allowing viewers to move easily between them.1

Pavilion Design of the 12th Istanbul Art Biennial by Ryue Nishizawa, 2011. Image © designboom.

Yet the design of the exhibition emphatically affirmed a nonhierarchical, nonsequential structure, which produced an idiosyncratic wandering, as each viewer found her own way through the different spaces. The large waterside warehouses (antrepo = entrepot)were filled with smaller freestanding structures, dry-walled on their interior and clad in silver corrugated steel on the outside. Each space was entirely contained by its own silver walls; each had its own dimensions, determined by the needs of the artwork on display. None of the structures were numbered on the giveaway map of the exhibition; instead the map was marked with the artists’ names. As a result, there was no sequence, no order, and no sense of one’s route being choreographed by a ghostly curator or designer.

As I walked from structure to structure, I was thrilled by the in-between spaces, narrow silver alleyways, not quite wide enough to form a corridor. These non-spaces set up a rhythm, a break between each encounter. There was a perpetual sense of making one’s own path through and between, standing in the open spaces and choosing which structure to enter, no possibility of the “next, next, next” consumption of a typical large exhibition. Some structures had multiple openings, allowing a through movement, and a few had only one, performing as a cul-de-sac, a punctuation mark. Occasionally the doorways in multiple structures lined up along an informal axis, providing an enfilade, a through view where distant artworks were brought into juxtaposition with the space in which one stood. There was a strong sense that these different sized structures, some small, some larger, some more square, some long and narrow, some open, some closed, were arranged like an irregular puzzle, a street market, or a city: a patchwork of some kind.2

The space that held the work of Bratescu was near the main entrance; it was relatively small, almost square, and had only one opening to the outside. The fifteen collages it contained were concise, complex variations on a theme: Vestigii. As such, this pavilion functioned not unlike Roland Barthes’s punctum, a moment of penetration and anchoring, like the buttons that pierce upholstery, producing the soft grid of tufted furniture. Throughout the show, the few cul-de-sac spaces provided a moment’s pause, a small interruption.

From this starting point, in this space and with this work, I was aware of a grid, somehow loosened, opened up, or embodied, and a sense of history, loss, and remains. The work in the entire exhibition elaborated on these themes, across national boundaries and decades. The classic claim of any biennial, that it provides a tasting menu of the up-to-date, was immediately upended, replaced by a sense of historical and geographic wandering and discovery. Indeed, the curators, Jens Hoffmann and Adriano Pedrosa, went to extraordinary lengths to examine critically and transform the usual patterns of biennial production, most specifically in their press announcement, which declared that the names of the participating artists would not be announced prior to the opening of the exhibition. There would be no scanning of lists of names to see who made it in, and who was excluded. There would be no possibility of deciding whether or not to attend the opening, based on one’s familiarity with the participants.3

This gesture could be seen as a kind of quixotic idealism in the context of an art world fueled by money and art fairs, yet it is an idealism that recalls Gonzalez-Torres’s thinking and practice. The viewer was implicitly invited to consider each artist’s relationship to the themes of each section, and to the works of Gonzalez-Torres that provided the larger context for each section. Untitled (Abstraction) was inspired by Gonzalez-Torres’s “Untitled” (Bloodwork—Steady Decline), 1994, a delicate graphite grid that invokes the deterioration of a person’s immune system under the onslaught of HIV. There were multiple squared forms in the (Abstraction) group show, including Cevdet Erek’s (Turkey, b. 1974) Anti-Pigeon Net (2010), which consisted of simply framed metal wire netting; Mona Hatoum’s (Lebanon, b. 1952) acutely fragile Untitled (Hair Grid with Knots 6) (2003); and Wilfredo Prieto’s (Cuba, b. 1978) Politically Correct(2009), a watermelon on the floor with its round edges sliced off, to become a rectangular cube, its blood red interior exposed.

The political dimension of this formal structure was revealed: the grid’s capacity to suppress organic idiosyncrasy and, indeed, perversity. Yet within the context of (Abstraction), the grid may equally propose the liberating potential of the diagram, the power of analysis. Lygia Clark’s (Brazil, 1920–1988) tabletop Bicho (Beast) (1960) recalled the playful, transformative possibilities of geometric forms, while DW(1967), by Charlotte Posenenske (Germany, 1930–1985), had similar qualities, taking the form of large rectangular cubes of corrugated cardboard, resembling air ducts or other hidden architectural elements. This piece invites the curator, collector, or installer to decide how many elements are to be installed and in what configuration, so despite the reference to architectural infrastructure, the work sustained an openness and sense of play.

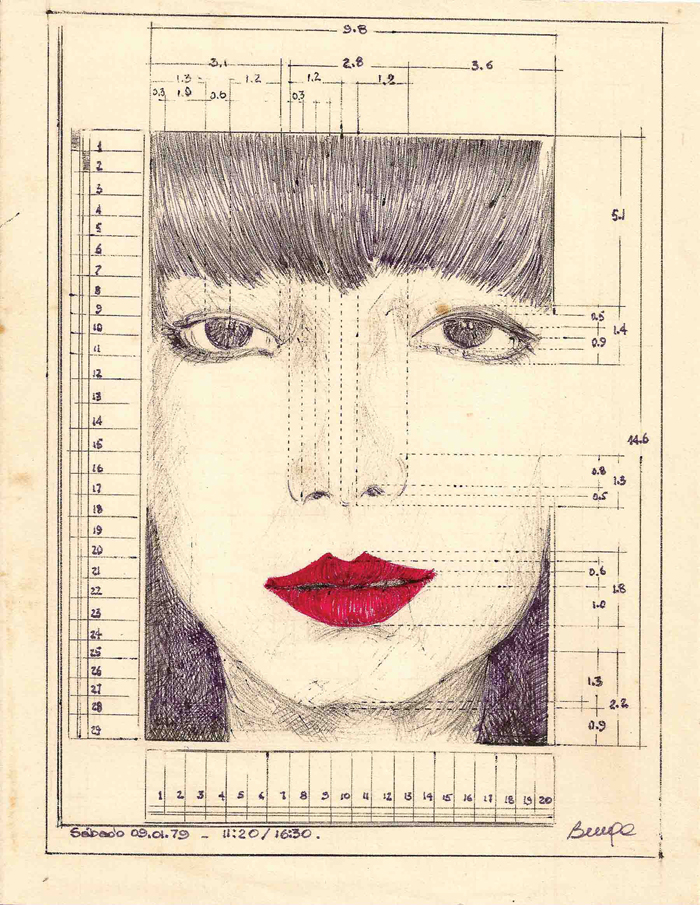

In the (Ross) section, Teresa Burga (Peru, b. 1935) showed her own interrogation of the system as system, in her Autorretrato(1972), which included black-and-white photographs of her face, printed on gridded paper, as well as medical analyses of blood samples and an electrocardiogram. All of these scientific samplings and measures were made during the course of one day, June 9, 1972, as if to underline the apparent objectivity of the project, yet the evidence was divided into three categories: “formless face structure,” “formless heart structure,” “formless blood structure.” The long history of pseudoscientific measuring of the bodies of different ethnic groups was invoked, together with the pressure towards an alienated perfection that too many women experience.

Teresa Burga, Untitled, 1979. ink and pencil on paper, 11.6 x 9.84 inches. Courtesy the artist.

At this point, another deep structure of the biennial emerged: there was a surprisingly large number of women artists in the solo shows, approximately half, and of them, an even more surprising number of older women artists. Of the fifty-four solo shows (four of which presented work by art collectives, and another four of which were pair collaborations), no less than nine presented work by individual women born before 1939. Including the artists from the five group shows, there were five additional women artists born before 1939. Most of these fourteen women were unfamiliar to many who visited the biennial, the most well known being Lygia Clark, Tina Modotti (Italy/ Mexico, 1886–1942), and Lygia Pape (Brazil, 1927–2004). The exhilarating depth charge of discovery extended from the architecture of the space to the individual artists within it.

Moving through the exhibition, I encountered internal rhymes, as when Bratescu’s textile pieces spoke to the extremely simple, sewn canvas wall piece in a nearby space, by another woman artist, Fusun Onur (Turkey, b. 1938). Here, the canvas edges come away from the plane, revealing worn gold underneath. This piece was itself echoed in the stunning room upstairs devoted to the Brazilian artist Leonilson (1957–1993). Shown within the context of (Ross), Leonilson’s work engages many of the questions found in the work of Gonzalez-Torres: distance, desire, queer sexuality, and love. In “Untitled”(1992), Leonilson layered a square of pale grey organza over deep orange, sewing them together across the top with a long row of hand stitches, in rich black embroidery thread. Hanging inside a frame from its top corners, this object has a drape, a dimension, like an empty pillowcase: looking sideways, you can see the two colors meeting at the seam. There’s an intimacy to this work that gives it an emotional intensity, always within the context of a minimalist aesthetic. Somehow these empty organza squares, with their pellucid colors and emphatic simplicity, invoke an absent body, while in other works, Leonilson embroidered words, to emphasize their handmade materiality, again embodying language and loss.

(Abstraction) conjured a body through the grid, the diagram, and the geometric. The section called (Ross) directly addressed gay identities, sexualities, and the catastrophe of AIDS, moving through celebrating sexual pleasure to mourning the dead. The work of Gonzalez-Torres that inspired this section was “Untitled” (Ross), 1991, which consists of “candies individually wrapped in variously colored cellophane, endless supply… (ideal weight: 79.4 kg).” Ross Laycock was Gonzalez-Torres’s partner, who died of AIDS in 1991. An infinite memorial to sweetness and temporality, the ideal weight may propose the sculpture as a stand-in for Ross’s healthy body. In solo shows, the extraordinary AIDS timeline by Group Material was placed near figurative pots from Ardmore Ceramic Art Studio in South Africa, which depict scenes of mourning, as well as men embracing and putting on condoms, both to educate about HIV and to commemorate their dead. In the (Ross) group show, Kutlug Ataman (Turkey, b. 1961) presented forever(2011), a mattress lying on the floor, sliced across and then partly sewn together, using gold and bright pink embroidery thread. The brilliant thread was over-sewn, resembling a scar or the zigzag of a medical chart.

Sometimes the echoes and rhymes were an effect of an artist’s work appearing in different locations, in two different group shows, or, as with Leonilson, in a solo show in one context (Ross), and also in a group show, (Abstraction). Ataman’s video work, Su (Water)(2009) showed seven horizontal strips of light reflected on bodies of water, the flickering light making the movement of the water both visible and invisible. It was placed in the (Passport) group show next door to (Ross), drawing a delicate line from Ataman’s rootless cosmopolitan identity (born in Turkey, he lives in Istanbul, Islamabad, and London), to a queer identity. In (Ross), Ataman also showed jars(2011), framed official documents that relieved him of the obligation to serve in the Turkish military, on the grounds of his homosexuality. The documents note that Ataman seems quite happy about his sexuality, as if this detail clinches their decision.

The section called (Passport) was structured around identity documents, visas, maps, and borders. It referred to Gonzalez- Torres’s “Untitled” (Passport #II), 1993, which takes the form of an unlimited stack of booklets, each printed with the image of a bird flying in a stormy sky. Birds traverse borders without impediment, despite or because of the wind that fills the sky with dark clouds. In stark contrast to this notion, Meric Algun Ringborg (Turkey/Sweden, b. 1983) showed The Concise Book of Visa Application Forms (2009–11), fat red volumes containing visa forms from every country, forms of indescribable tedium, yet with the unspoken potential to transform lives. Baha Boukhari (Jerusalem, Palestine, b. 1944) presented My Father’s Palestinian Nationality (2007), a vitrine containing her father’s various identity papers, including passports issued by the High Commissioner for Palestine from 1924 to 1948, when the British Mandate ended. Finally there is an ID card issued by the Government of Palestine. These passports were echoed in Sue Williamson’s (United Kingdom/South Africa, b. 1941) For Thirty Years Next to his Heart (1990), a grid of forty-nine framed scans, showing each page of a black South African’s passbook, verifying his identity and employment over a period of thirty years. While these works might seem heavy handed, the impact of them in situ was very different. This was partly due to the historical presence of the specific documents, partly the simplicity and lack of commentary in the presentation and partly the sense of the impossibility of life without documents. Identity documents function as another kind of trace, a kind of memorial to different geographic and political histories. Zarina Hashmi (India/New York, b. 1937) showed quietly powerful woodcuts of maps of different places, titled Atlas of My World (2001). It seemed as if a large proportion of the artists in the biennial were exiles and wayfarers, underlining the themes of shifting identity and trans-nationality.4

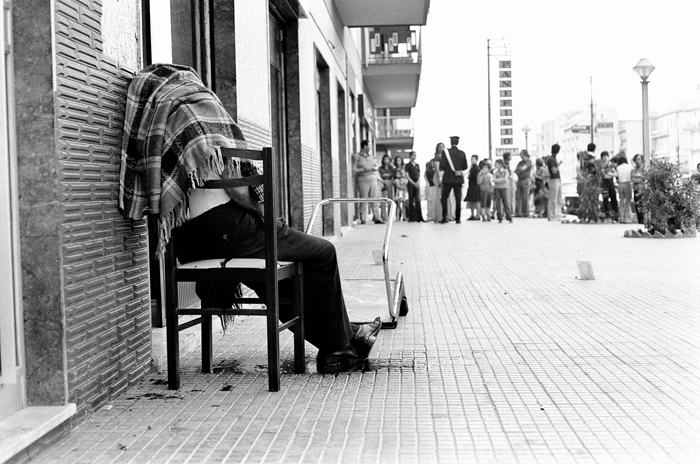

To return to the fourteen older women artists, I noted that a number of them were photographers, operating within a context of documentary photography and using black-and-white film. Yildiz Moran Arun (Turkey, 1932–1995) was the first formally educated female photographer in Turkey, active from 1950–1962, and her quiet photographs of Anatolian people and landscapes recall the arid spaces and intense presence of Tina Modotti’s subjects. Claudia Andujar (Switzerland/Brazil, b. 1931) spent decades working with the Yanomami Indians of the Amazon. Her Marcados (Marked) (1981–83) presents a grid of black-and-white individual ID photos of Yanomami people, each one wearing a number, a reiteration of a nineteenth century system of identification. Repeating the tropes of colonial anthropology in order to call them into question, these images were both compelling and disturbing. Letizia Battaglia (Italy, b. 1935) made thousands of black-and-white photos related to mafia violence while working for a Palermo daily paper from 1975. The images presented here showed corpses lying as they were found, in ordinary streets, cafes, and domestic interiors. Each had an explanatory caption as its title: Palermo, 1976. They killed him while he was going into the garage to get his car (1976). There was a deep sense of everyday life infused with the imminent possibility of extreme violence, which connected to the collage work of Martha Rosler (United States, b. 1943), Bringing the War Home (1967–72), also included in the (Death by Gun) section of the biennial, as well as Mark Bradford’s (United States, b. 1961) Rat-Catcher of Hamelin (2011), a massive poster collage referring to the Los Angeles serial killer known as the Grim Sleeper. Another older woman artist, Rozsa Polgar (Hungary, b. 1936), was represented by a single powerful work, Soldier Blanket 1945(1980), another worn textile, a faded brown blanket folded simply, with a blood-stained bullet hole marking it.

Letizia Battaglia, Palermo, 1975. A Murdered Man Sits in a Chair, 1975. gelatin silver print, 19.7 x 23.6 inches. Courtesy the artist.

For me the most powerful solo show in the (Death by Gun) section was by Bisan Abu-Eisheh (Jerusalem, Palestine, b. 1985). Playing House(2008–11) presented a room full of vitrines containing ordinary objects and architectural fragments remaining from the demolition of Palestinian houses in Jerusalem. A very brief video from YouTube showed the explosive demolition of such a house, maybe three stories, closely surrounded by other similar houses. I moved back and forth, from the fascination of these silent, broken relics to the sudden, jarring explosion, all over in an instant, repeating the incomprehensible reality.

Bisan Abu-Eisheh, Playing House, 2008–11. installation (vitrines, collected objects, and research documents) and video. Courtesy the artist.

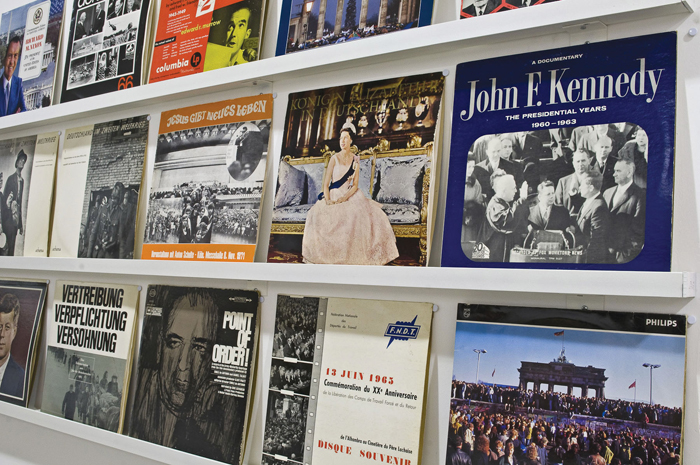

A mental echo linked this work to the solo show by Dani Gal (Israel/Germany, b. 1966) across the way in (History). Here Gal showed his Historical Record Archive (2005–ongoing), a vast collection of vinyl LPs, each a commercially produced recording of an historical event: Mai 68, Hitlerjugend, The Great March to Freedom (Detroit June 23, 1963), The Six Day War. The relentlessly silent LPs lined the room in their sleeves, facing outward and generating all kinds of fantasies regarding their contents. The (History) section of the show emphasized the writing and re-writing of history, the logic of the archive, and the overlay of different historical moments and places. The work of Gonzalez-Torres it referenced is “Untitled” (1988), one of his dateline works, where names and dates appear in white type on a black field, juxtaposing political and popular names and events. In this case, the names include Patty Hearst 1975, Watergate 1973, Bruce Lee 1973, Munich 1972, Waterbeds 1971. Presented in the context of (History), the oldest living artist in the show was an African American woman, Elizabeth Catlett (United States/Mexico, b. 1915), whose woodcuts and posters from the 1960s and 1970s spoke of the civil rights movement and Black Power. Living in Mexico since 1940, and profoundly influenced by Mexican printmaking, her work reaches back across the decades, connecting a contemporary moment to histories of union activism and struggles against racism and for social change.

Dani Gal, The Historical Records Archive, 2005–ongoing. vinyl records, dimensions variable. Installation view, Herzliya Museum, Herzliya, Israel. Courtesy the artist and Freymond-Guth Fine Arts, Zurich, Switzerland. Photo: Yigal Pardo.

In the context of (Passport), Taysir Batniji (Gaza/France, b. 1966) showed twenty-six black-and-white photographs of Israeli military watchtowers (Miradors[Watchtowers], 2008) on the West Bank, framed in a grid that consciously imitates Bernd and Hilla Becher’s photos of industrial structures. Born in Gaza, Batniji is not allowed to enter the West Bank, and therefore these photographs were taken by another, un-named Palestinian photographer. While the Bechers’ work is meticulous, these photos were necessarily clandestine, and therefore imperfect. The discrete sets of watchtowers had a haphazard quality, as if each iteration of the form allowed another variation, another version of surveillance and control.

At the other end of the spectrum, Dora Maurer (Hungary, b. 1937) used black-and-white photography to document her experiments with formal displacements and two-dimensional mappings of three-dimensional space. Her piece Seven Rotations 1-6 (1979) shows a sequence of photos of the artist, the first holding a blank square of paper to make a diamond shape in the frame, partly covering her face. Each subsequent photo showed her holding up the previous photograph, in precisely the same configuration, her glance over the top corner changing as she moved through the sequence. In Throwing the plate from very high (1970), she dropped an etching plate off a Budapest apartment block balcony, documenting this action in three black-and-white images, and printed the resulting plate, a two-dimensional indexical tracing of a three dimensional crumple. Throughout the 1970s, Maurer used photographs to map space, and drew diagrams based on these photos: people walking together, plants blowing, a man kicking a soccer ball around. Equally concise and mysterious are her folded paper works (Hidden Structures Series, 1977) in which different geometric folds in rectangular drawing paper produce extremely simple and then increasingly complex forms. Looking at the creases, we mentally fold and unfold the paper, just as we follow her photographic “space tracing” and diagramming of chance events. Again, this work interrogates the logic of the grid and systems of registration, exposing their limits as well as their potential for representation. The ordinary moment became the stuff of her investigation, taking me back to Geta Bratescu’s bag of scraps and patches, odd and idiosyncratic records of women’s lived histories.

Dora Maurer, Seven Rotations, 1979. Number six in a series of six gelatin silver prints, 9 x 9 inches each. Courtesy Vintage Gallery.

The final group show was titled after Gonzalez-Torres’s work “Untitled” (Death by Gun), 1990, an unlimited stack of posters presenting a grid of 460 people killed by gunshot in the United States during the week of May 1–7, 1989. Appropriated from Time magazine (July 17, 1989), the dead are listed by name, age, city, and state, with brief descriptions of the circumstances of their deaths and in most cases a small ID photo. (Death by Gun) presented more black-and-white photographs, placing Chris Burden’s (United States, b. 1946) Shoot (1971) next to unforgettable photos by Eddie Adams (United States, 1933–2004), including Street Execution of a Viet Cong Prisoner, Saigon (1968). Mathew Brady’s (United States, 1822–1896) civil war photos of dead young men on the battlefield connected these images to a history of documentary photography, while foregrounding an erotic pleasure in looking. Brady’s explanatory captions recalled Battaglia’s, while the weight and presence of these images of dead bodies hovered between a desensitized familiarity and a painful recognition.5 Akram Zaatari (Lebanon, b. 1966) presented his borrowings from the black-and-white photographic archive of Hashem el Madani, a Lebanese commercial photographer working in the same studio for over fifty years. In these portraits, men and women posed with guns, dressed up in military masquerade, while in the (Ross)section, images from the same archive showed men embracing men, women embracing women, as if the artificial space of the photographic studio opened up a free zone of fantasy and pleasure.

Akram Zaatari, El Madani-Studio Practices–Couples, 2007. Modern silver print from 35-mm negatives, 11.5 x 7.5 inches. Courtesy the artist and Galerie Sfeir-Semler, Beirut, Lebanon.

In the group show (Ross), Michael Elmgreen (Denmark/United Kingdom, b. 1961) and Ingar Dragset (Norway/Germany, b. 1969) showed Black and White Diary, Fig. 5(2009), a collection of 364 black-and-white photographs documenting friends and lovers, informal snapshots of men hanging out, having a good time together, with lots of pictures of cocks and bars and tourist jaunts. These were displayed in a long corridor, framed in white pleather and placed on crowded shelves. Like so much of the work in the biennial, there were different core samples to be taken, different contexts to activate: queer sexuality, or black-and-white photography, or the writing of history, or transnational identities, or all of the above.

Untitled (12th Istanbul Biennial) was big, but the detail and clarity of its structure allowed for sustained engagement and appreciation of the threads of connection running through it. One could argue that the strongest historical link was to the 1970s, as if contemporary art looks for its mothers (and fathers) there.6An aesthetic consistency (black-and-white photographs, post-minimalist forms) also worked to make the show coherent, and paradoxically this in turn produced the openness that allowed each viewer’s idiosyncratic reading of the show, as connections were drawn across the sections, linking different geographies and histories to particular ideas or issues. My own fascination with the subset of women artists born before 1939 could be paralleled with another viewer’s interest in artists from the Middle East or South America, in archives, or documentary photography. In a fundamental sense, the show argued for subjectivity as layered, contradictory, and incomplete, articulated in part through sexuality and the writing of history, in part through the registration of the body within systems of representation and authority. Above and beyond these various articulations, the curators placed the language and logic of the gun, casting the shadow of lethal violence over all these ideas and possibilities. Yet a balance was struck: the simplicity, coherence, and clarity of the presentation of the artworks were crucial, producing a perpetual sense of discovery in the encounter with each artist’s work.

Leslie Dick is a writer and artist who lives in Los Angeles. She teaches at CalArts and is a member of the editorial board of X-TRA.