Over 17 days in July and August 2018, a mother orca named J35 carried the body of her dead calf atop her nose around the Salish Sea on the northwest coast of North America. Orcas are apex predators, demonstrating complex social behaviors and a matrilineal family pod structure. The resident killer whales of the Salish Sea are currently listed as an endangered population, and J35 had already lost one or more offspring to starvation due to salmon overfishing in the region. Supported by her herd, who surrounded and fed her, the whale persevered in her mourning long beyond any length of time previously observed by researchers.1 In her ritual, J35 embodied the sentience of the ocean.

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015. Three channel HD color video installation, 7.1 sound, 48:30 min. Installation view, Sublime Seas: John Akomfrah and J. M. W. Turner, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, March 3–September 16, 2018. © Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

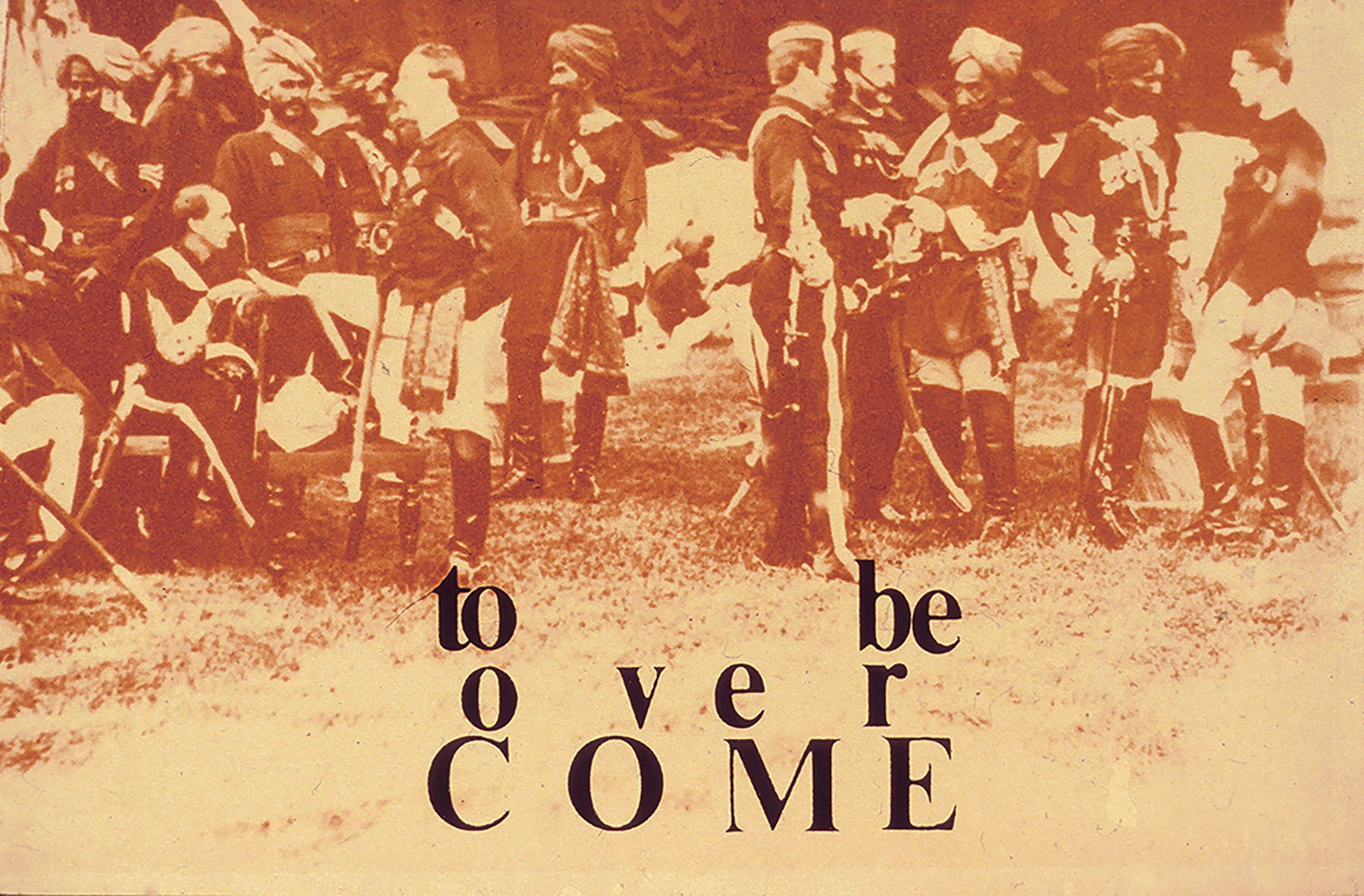

To understand the ocean as sentient is to imagine the earth as self-aware, able to feel and respond to actions enacted upon it. This possibility emerges from John Akomfrah’s three-channel epic Vertigo Sea (2015). In the summer of 2018, Vertigo Sea was the centerpiece of two exhibitions of Akomfrah’s work, at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art and at the New Museum, in New York. The film, which premiered at the 2015 Venice Biennale, enlists Akomfrah’s signature montage techniques to integrate footage from newsreels and from five decades of the BBC Natural History Unit’s archive within the artist’s narrative. The sea itself becomes a character—the Vertigo Sea—that bears witness to the beauty of the natural world and to the terrible destruction wrought by humans over centuries of exploitation. Vertigo Sea is more cinematic than Akomfrah’s earlier montage works, achieving spectacular scale through its use of professional footage from the BBC unit best known for majestic nature documentaries such as Blue Planet. Though dazzling in full color, 4K (high resolution) detail, Vertigo Sea is constructed with the same appropriation and remix techniques that Akomfrah’s earlier works brought from popular culture into the cinema. An early film on view at the New Museum, Expeditions 1–Signs of Empire (1983), by John Akomfrah with Black Audio Film Collective, demonstrates these technical similarities and makes the artist’s enormous range of aesthetic capabilities apparent. This work combines images of neoclassical sculpture from British heritage and government sites with overlaid text that hints at other, postcolonial meanings for the forms on display, articulating the colonial fantasy that results in the production of Empire as a dream-state. Vertigo Sea, at just under 50 minutes in length, similarly blends visual references to prior eras of Western history with texts that challenge valorization of these periods. Vertigo Sea intercuts footage of white and black characters in eighteenth-century European dress with quotes from literary sources, including Moby Dick (1851) and the first-person narrative of the former slave Olaudah Equiano, who is described in most accounts as a West African-born survivor of the transatlantic passage and who profoundly influenced the British abolitionist movement. These linguistic and visual connections describe the sea as the repository for all the crimes of Empire: from enslaved Africans cruelly thrown into the Atlantic to desperate migrants and refugees sinking and drowning in the Adriatic, to the creatures of the Arctic struggling to survive atop receding ice caps as their resources diminish ever more under human dominion.

John Akomfrah, Expeditions 1 – Signs of Empire, 1983. Video still. Single-channel 35mm color Ektachrome slides transferred to video, sound, 26 min. © Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

Black Audio Film Collective (active 1982–98) included seven British filmmakers of African and South Asian heritage, three of whom—Lina Gopaul, David Lawson, and Akomfrah—would go on to found Smoking Dogs Films.2 These artists were among a generation of 1980s British artists of color who advanced visual techniques for negotiating the cultural baggage of Empire in film and video works. Raised in the United Kingdom by parents from former colonies, including Ghana, India, and Jamaica, these artists were caught between an education and patronage system that favored fluency with Western classical literature and art and a desire to investigate and reflect cultural narratives in line with their own histories and experiences. Black Audio Film Collective sought to reconcile and represent these discrepancies as a unified Black British aesthetic. Their approach was to bring together practitioners from different professional backgrounds, both within and outside the arts, to create films in which the dialogue of the collective itself could be reflected in the images on screen. In an era characterized by racial violence and uprisings taking place across Britain, Black Audio Film Collective’s goal was to counter the dominant cultural narratives of imperialism and exclusion with an alternative vision that was constructive, inclusive, and inarguably British.3

John Akomfrah, The Unfinished Conversation, 2012. Three-channel HD video installation, 7.1 sound, color, 45:48 min. Installation view, John Akomfrah: Signs of Empire, New Museum, New York, June 20–September 2, 2018. © Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

The New Museum exhibition surveys 35 years of Akomfrah’s practice and includes two more recent works, The Unfinished Conversation (2012) and Transfigured Night (2013/18). The former is a three-channel installation based on the life and writings of Stuart Hall, the generative Jamaican-British postcolonial thinker who narrated the visual deconstruction of classed, gendered, and raced cultural tropes through the advent of non-hierarchical assemblage forms in popular art and auditory equivalents in jazz and hip-hop music. Hall promoted the study of vernacular visual culture in the 1980s and 1990s as a scholarly discipline, a position rejected by many of his mentors and peers. Transfigured Night is a two-channel installation drawing on the twentieth-century history of the Ivory Coast. The film narrates the failed aspirations of the Third World Liberation movement, told through the story of Ivory Coast’s first president, Félix Houphouët-Boigny, and incorporating the words of Kwame Nkrumah, his Ghanaian counterpart. The president’s efforts to lead his nation into industrialization and economic self-sufficiency while maintaining unity across ethnic divisions were maintained through a one-party system, which ultimately failed to provide his people with democratic rule of law.

These works employ deconstructionist or conceptualist methods of comparison and contrast to juxtapose images that sometimes do not resolve into visual harmony. This is fitting for the subjects of the works, each of which deals with the challenges of self-construction in the aftermath of an incomplete project of racial liberation. Transfigured Night addresses the onset of emotional or affective politics in postcolonial Africa, focusing on the use by recent leaders and governments of popularity and celebrity to deflect from their shortcomings. The Unfinished Conversation sets out to document the influence and scope of Stuart Hall’s thinking in an aesthetic manner befitting his boundary-defying approach to the study of visual culture. Both works reckon with midcentury heroes and the failures of nations to support the egalitarian and human-centered ideals on which their constitutions are based.

John Akomfrah, Transfigured Night, 2013. Two-channel HD video installation, 5.1 sound, color, 26:31 min. Installation view, John Akomfrah: Signs of Empire, New Museum, New York, June 20–September 2, 2018. © Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

In Vertigo Sea, black men languish in the hold of a ship, several men stuffed into a bunk. Their searching eyes contrast with the suspended animation of their bodies. Below, the ocean churns with vitality. Massive humpbacks breach and dive, their black skins luminous. An indignant voice booms: “A mate of a ship, in a long-boat, purchased a young woman, with a fine child, of about a year old, in her arms.” The waters pulsate beneath the boat. “In the night, the child cried much, and disturbed his sleep. He rose up in great anger…tore the child from the mother, and threw it into the sea.”4 Newsreel footage shows white ship’s mates forcing shirtless black men overboard in a reenactment of the Zong massacre of 1781, in which 133 enslaved Africans were deliberately drowned by British slave traders in an insurance scheme. In an ensuing scene, the carcass of a whale is dragged across a ship’s deck on a hook. The whale, like the men, is worth more dead than alive in the accounting ledger.

Orca J35 had a podmate, a juvenile called J50, whom the researchers watched with interest during J35’s grieving ritual for the dead calf. J50 was one of the few young whales in the pod who survived into adolescence. This whale was known as Scarlet because of reddish rake marks near her dorsal fin, which reports describe as evidence of other whales in the pod having midwifed her and pulled her free of her mother during a breech birth. As of mid-September 2018, Scarlet was no longer seen with the pod and was presumed dead.5 The pod, which has not had a viable live birth in over three years, is thought to have about five years left of reproductive viability before the community as a whole is condemned to die out.6 Meanwhile J35 is now said by researchers to be healthy and recovering from the loss of the baby that she carried for 17 months in the womb.

Christina Sharpe describes the condition of black motherhood in the United States by making an analogy between the mother’s body and the ship that could also be applied to the whale. “The belly of the ship births blackness; the birth canal remains in, and as, the hold.”7 The expectant black mother understands her unborn child as birthed into non-being; as always marked for potential death due to his or her lack of full personhood in the eyes of the state. For Sharpe, the “wake,” like the ship’s trace on the water, is the trail of poverty, illness, and trauma that follows black people over generations after Emancipation. The “weather,” in Sharpe’s lexicon, is the general climate of anti-blackness that makes it difficult for people to live—but this need not be understood metaphorically, as weather in the form of climate change is very much upon us. Akomfrah’s Vertigo Sea is informed by Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness (1993), which draws parallels between the violence enacted on black subjects, specifically enslaved Africans, and the devastation of indigenous communities and environmental resources through Western-style capitalism. The looming question of climate change is everywhere in Vertigo Sea. With the United Nations warning that only 12 years remain for any meaningful reduction in global warming to occur, the realities of irreversible global warming may well force humans into “deep adaptation” behaviors that look very different than our current social priorities and may even cause our societies and communities to collapse.8 Adaptation may also mean that even the most privileged humans come to again accept as given that some number of their young may not survive, a condition that modernity promised to eliminate rather than engineer.

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015. Video still. Three channel HD color video installation, 7.1 sound, 48:30 min. © Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

A lone black figure stands upon the shore of the Vertigo Sea. His dark skin and silk clothing mark him as an African of the Western world. This is Olaudah Equiano, whose autobiographical narrative helped to end the transatlantic slave trade in Britain. Paul Gilroy describes Equiano as a figure whose “involvement in the beginnings of working-class politics is now being recognized.”9 The Igboborn Equiano was abducted via ship, an experience that figures heavily in his book, and worked at sea as both a free and enslaved laborer. As a freed man, Equiano played a part in colonial explorations of the Arctic and Central America, rendering him an early example of capitalism’s entreaty to rehabilitate the enslaved as overseers through conquest of ever more wretched peoples. Equiano did not submit to this request, instead establishing himself as a prominent voice in opposition to forced labor conditions around the globe.10 He was instrumental in publicizing the Zong massacre of 1781. Though unable to secure conviction of the ship’s crew for murder, Equiano and his allies were able to leverage the Zong incident to rally popular opinion in Britain against the transatlantic slave trade, which was finally made illegal within the British Empire in 1807.

For Akomfrah, who came of age in 1980s London as a figure in the Black Arts Movement amid Caribbean, African, and South Asian-descended peers, the montage of original and appropriated film footage epitomizes the selection and remixing that characterizes contemporary postcolonial thought. Black Audio Film Collective helped give rise to a new genre—speculative documentary—in which archival and interview footage prompt imaginative, future-oriented discourses to emerge from contested historical narratives. Gilroy describes montage as a revolutionary technique, and he ascribes it to vaudevillians, such as the black anti-racist performers the Fisk Jubilee Singers in the antebellum South, who were canonized in W. E. B. Du Bois’s The Souls of Black Folk.11 For black artists, the loss of history and collective narratives can operate as a kind of muteness that becomes a subject in itself. Appropriation offers a way to speak freely through imposed constraints. An intertextual example is the book-length poem Zong! (2008) by M. NourbeSe Phillip, which narrates the inhuman actions aboard the Zong using only the language of the resulting court decision, Gregson v. Gilbert (1783), and the visual forms of the words and letters on the page.

Sublime Seas: John Akomfrah and J. M. W. Turner, installation view, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, March 3–September 16, 2018. Courtesy of SFMOMA. Photo: Katherine du Tiel.

In Vertigo Sea, the ocean’s power to cajole or terrorize is poetically linked to that of Empire, and the sublime aesthetics of romanticism are put to dramatic effect in the service of that narrative. Simultaneous views of the sea, shown from above and below, across the work’s three channels, reinforce the idea that human bodies and those of other mammals, such as whales, seals, and polar bears, are contiguous. The ocean appears as a political and economic space as well as an environmental one, traversed by colonial ships that carry African captives to enslavement, by whaling ships that strip the sea of life, and by cargo ships powered by fossil fuels that massively deplete the planet’s resources. A Black British aesthetic emerges: one that visualizes the earth with the magnitude and sweep of Empire, but absent its callousness, infused instead with concern and compassion for the victimized and exploited. Dark and foreboding images of ships’ holds, dismembered creatures, and fragmenting polar sea ice intermingle with effervescent flocks of white birds and hopeful rays of sunlight peeking through storm-wracked sea plants.

At SFMOMA, Vertigo Sea was installed adjacent to J. M. W. Turner’s The Deluge (1805), which the museum borrowed from the Tate, in London, at Akomfrah’s request. Turner’s painting of a ship overturning in a biblical flood helped to establish the Sublime as the prevailing aesthetic of the Romantic period, rendering both the beauty and the terror of the ocean with sweeping waves and a distant, burning sunrise. Human bodies, mostly white, flail against the shore. In the upper left, a silhouetted palm tree, a botanical transplant connecting Old World Orientalism with the New World, threatens to capsize next. In the lower right, a sturdy black man steadies and shelters a flaccid, nude white woman. Another white woman in the foreground clings to the shreds of her Victorian decency, covering her breasts with the remnants of her dress and turning modestly away from the viewer’s gaze. In Akomfrah’s video, projected onto the three screens opposite, ocean waters swarm with debris, the murky sea floor stirred up by a coming storm.

Turner was both a proponent of the Romantic philosophy, which equated Nature with an untamed and even hostile Other, and an avid abolitionist who deliberately placed a heroic black figure prominently within his masterwork. The biblical flood swept away all but the righteous, and the few figures who appear to have survived in Turner’s painting fit the universalist aspirations of the Romantic, including the modest woman, the noble African, and small children, one of whom has survived atop his mother’s outstretched arm while she languishes below in self-sacrifice. In Vertigo Sea, the survivors of the Deluge have restored their Victorian propriety. They are shown on a wild, rocky shore, properly outfitted in dresses, waistcoats, and tri-cornered hats as they rest amid strewn bits of furniture: a mahogany Louis XVI-style chair, a piano, a baby’s crib. Faced with near-total loss, the need to reestablish social codes speaks to the fundamental anxiety of the colonial period: the fear of the “civilized” man’s descent into “savagery,” abetted by a desire for companionship that racial and cultural “Others” could readily fill; this anxiety led to white Victorian women being encouraged to emigrate from Europe to the colonies and to the advent of the family homestead and the resulting establishment of contemporary settler colonialism.

Joseph Mallord William Turner, The Deluge, exhibited 1805. Oil paint on canvas, 70 ⅞ x 106 ½ x 5 in. Courtesy of Tate, London.

The Black Atlantic is a living archive, but it is a graveyard. It documents only absence. Any memories transmitted are in the living text. “Staging for the end of history,” writes Jacques Derrida, as he coins the term hauntology: “this logic of haunting…would harbor within itself… eschatology and teleology themselves. It would comprehend them, but incomprehensibly.” 12 Life that can no longer be extracted is dumped into the ocean: plastic trash, radioactive waste, economically unproductive infants, political prisoners on “death flights.” All of this death serves a profit motive, but that pales in recognition of the totality of life and death that the ocean represents, which is difficult to reduce to metaphor, or to articulate in words.

The Zong massacre is a prime example of what Fred Moten and Stefano Harney call “logisticality, or the shipped”: “Modern logistics is founded with the first great movement of commodities, the ones that could speak.”13 In contrast to the industrious and often physically violent activity taking place on the ship’s deck, Moten and Harney describe how, in the hold of the ship, the clock of logistical efficiency is rendered impotent. The Zong incident illustrates the logic by which enslavement under capitalism pits the value of living labor against the commodity value of the body itself, and finds life lacking. “Indeed logistics and financialization worked together in both phases of innovation, with, roughly speaking, the first working on production across bodies, the second renovating the subject of production.” 14 If logistics demanded moving African bodies across the Middle Passage, financialization demanded that some bodies be drowned to maintain their ideal conversion into capital. Other bodies would survive the passage, but none would proceed without catastrophic personal losses. This devastation is part of what Moten and Harney call the “renovation,” or forced assimilation, to which captive Africans were subjected, as they were systematically denied their names, languages, communities, and faiths.

Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic shares the pessimism of Moten and Harney but embraces the Atlantic as a site of vibrant cultural and socioeconomic activity fostered by black migration. This global trajectory, established through the transit of enslaved people from the west coast of Africa first to Europe, then across the ocean to the West Indies and culminating in North and South America, offers a fruitful space for black political thought that is not limited by homogenizing North American popular culture conceptions of the black experience. The Atlantic connects African cultural traditions with a concept of Diaspora that Gilroy and others have borrowed from Jewish traditions of culture-keeping in exile. Gilroy describes the Atlantic as a system of cultural production anchored in black radical thought, producing liberatory figures like Toussaint L’Ouverture, Denmark Vesey, and Crispus Attucks.15

John Akomfrah, Vertigo Sea, 2015. Three channel HD color video installation, 7.1 sound, 48:30 min. Installation view, Sublime Seas: John Akomfrah and J. M. W. Turner, San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, San Francisco, March 3–September 16, 2018. © Smoking Dogs Films. Courtesy of Lisson Gallery.

A boat full of Vietnamese refugees capsizes in the South China Sea, just yards from the shore. Adults scramble to fish small children and elderly people out of the knee-deep waters. Between 1975 and 1995, almost 800,000 Vietnamese refugees survived this crossing, while another 400,000 are estimated to have drowned.16 This crisis played out in the media at a formative moment for Akomfrah, who was born in 1957 and emigrated from Ghana to the United Kingdom at age four. Recent footage of Nigerian and Syrian migrants trying to cross the Mediterranean brought these associations back to the artist’s mind.17 Their losses—material and physical, yes, but also the total loss of being that the sea confers as it carries the migrant to a new, anonymous condition—resonate with the words of Caribbean poet Derek Walcott:

Where are your monuments, your

battles, martyrs?Where is your tribal memory? Sirs,

in that grey vault. The sea. The sea

has locked them up. The sea is

History.18

Walcott describes an ocean that is comprehending, but incomprehensible to us. “But the ocean kept turning blank pages / looking for History,” he writes. Akomfrah speaks of the different cultural interpretations that inform reception of his work, so that his work is received one way in London, where popular awareness of migration in Britain and the country’s history of colonialism is commonplace, if contentious, and another way in Denmark, where the commercial and cultural history of whaling is more commonly held in the national consciousness, while cultural diversity and colonial legacies are treated by Danes as new and difficult subjects.19 What we choose to remember creates a shape around what we choose to forget.

It’s all subtle and submarine,

through colonnades of coral,past the gothic windows of sea-fans

to where the crusty grouper,

onyx-eyed,

blinks, weighted by its jewels, like

a bald queen;and these groined caves with

barnacles

pitted like stone

are our cathedrals20

In early 2018, artists Jeannette Ehlers and La Vaughn Belle installed their monumental sculpture, I Am Queen Mary, to commemorate a woman-led labor uprising on the centennial of Denmark’s sale of St. Croix to the United States. Mary Thomas led the Fireburn, on St. Croix, in 1878, burning plantations in protest of oppressive wage conditions for newly un-enslaved African laborers. 21Thomas was convicted by a Danish court and imprisoned in Copenhagen, along with two other women. Together, they would become known as the Three Rebel Queens of the Virgin Islands. Ehlers and Belle’s Queen Mary gazes out over the Øresund, the sound that separates Copenhagen from Malmö, Sweden, and connects the Baltic Sea to the Atlantic Ocean. In one hand, she holds a blade for cutting sugar cane, in the other, a torch. She is seated on a rattan chair, nearly 23 feet high atop a pedestal embedded with chunks of coral. Behind her is a warehouse that stored Caribbean sugar and rum during the nineteenth century, when Denmark maintained colonial interests in her home of St. Croix, Virgin Islands. A mile to the south is the prison where she was once incarcerated.22 Mary was a mother, but she was no paragon of Victorian saintliness. The uprising that she led set fire to nearly 900 acres of plantation farmland and killed at least 75 people.

Queen Mary’s straight-backed posture and the shape of her “throne” emulate the iconic 1967 photograph of Black Panther Party leader Huey P. Newton, in which he sits in a wicker chair, holding an African spear in his left hand and an assault rifle in the right. While The Black Atlantic is overwhelmingly critical of the outsized influence American popular culture has had on global conceptions of racial consciousness, Gilroy acknowledges moments in history when black liberatory consciousness has been forged in solidarity between African Americans and other Africans of the Diaspora, including Newton’s recognition of anti-slavery histories and black resistance in the Caribbean as precursors to his own aspirations. For Ehlers and Belle, erecting a monument commemorating a black woman from the colonies is equally significant in informing Danes of all races about their country’s colonial past and moving the country beyond the xenophobia that is presently ascendant to a time when migration could be recognized as the mutual history of humankind.

La Vaughn Belle and Jeannette Ehlers, I Am Queen Mary, 2018. Polystyrene, coral stones, concrete, 275 1/2 × 128 3/4 ×153 1/4 in. Courtesy of the artists. Photo: David Berg.

The coral chunks that make up Queen Mary’s pedestal were originally cut from the ocean near St. Croix by enslaved Africans and used to construct colonial-era houses that have since fallen into ruin. This material is rendered sacred by its having passed through enslaved hands and by its having been the headstone at the grave of so many drowned in the sea.

Then there were the packed cries,

the shit, the moaning:Exodus.

Bone soldered by coral to bone,

mosaics

mantled by the benediction of

the shark’s shadow23

Vertigo Sea’s most revolutionary aspect may be its slow and deliberate construction of time, which flows at the pace of the ocean, moving according to gravitational forces and in opposition to the industrialized brutality of the clock. The work presents a whale’s perspective, keeping us below the surface for as long as possible, then coming up for an aerial view. The film ebbs and flows in five transfixing cycles; its totality makes the case that humans’ relationship to the ocean has been logistical in ways that exceed, yet contain, the ongoing traumas of the Middle Passage. The Vertigo Sea as depicted by Akomfrah is much greater than our relationship to it. It is the earth’s sentient engine, fertilizing future growth even as it silently tallies all of global capitalism’s terrible receipts. Down below, Walcott’s “benediction of the shark’s shadow” passes over the crusted barnacles in a drowned woman’s hair as she whispers her ghost story into the ocean.

Anuradha Vikram is a curator, educator, and writer based in Los Angeles. Vikram is a member of X-TRA’s Editorial Board.