The Geffen Contemporary is an enormous space. Rather than filling it with objects, William Pope.L has composed his monographic exhibition Trinket around a central colossal gesture. Powered by special-effects fans, a 16-by-54-foot star-spangled banner whips through the sonorous 19,000-square-foot main space to a choreographed sequence of dramatic light. Although its title, Trinket (2008/15), may be ironic, its presence cannot be. “Like any ritual object the flag does things to us. Shapes our behavior, our reality,” Pope.L writes in the brochure essay. The flag is. The flag does. The flag means. The impossible co-existence of these functions leaves this viewer stunned—frozen somewhere between a tamed animal and one caught in the headlights.

Installation view of William Pope.L: Trinket, March 20–June 28, 2015, at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. William Pope.L, Trinket, 2008/2015. Mixed media, 16 × 45 feet. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Ryan O’Connor.

But which one is it? The tamed animal, subject of ideology, responds to her training; the wild animal is immobilized by a physical predisposition to the commanding presence of the object. The former acquired, the latter innate—what is it that has now seized my existence, despite thirty-odd years of intellectual work to resist external modes of coercion? A flag of urban scale relocated indoors, its magnitude, motion, and symbolism amplifying its ability to affect monumentality. My submission to this object starts on a cellular level and ends at the hands of nation-state ideology. My inability to answer my own question keeps me standing, staring, circulating, and returning. I observe others: contemplating, photographing, videotaping, relating. No one, it is assumed, steps into a museum of contemporary art and takes things at face value. What is their relation to this event? What is my relationship to this collective?

The work casts in relief a series of contradictions that unfold between the state and the citizen, the citizen and the human, the human and her identity, identity and subjectivity, and the subject and its biological infrastructure, which is itself organized by the state and ordered by language. Contradictions are enacted in and by the other works traversing the Geffen’s spaces, most of them official, a few appearing unlabeled or unmentioned, all weaving in and out of each other.

Contradictions appear in the synapses between the sensory operation of the work and its existence as sets of signifying gestures that point to the material world. The affect and effect of such contradictions can be understood through five paradigms (more, but for now the hexagonal will suffice):

Aesthetic: I am mesmerized against my intellectual grain.

Phenomenological: Being is a tension between a sensory body and a thinking mind.

Marxist: A flag inside a contemporary art museum cannot not represent class contradiction.

Psychoanalytic: The subject is a moving compromise between subjugation and agency.

Semiotic: We flicker in the coexistence of representation and reality.

Let us start with the semiotic for its penchant to both animate and explain things. Beyond its designation as a living being by the order of the law (4 U.S. Code § 8 — Respect for flag), the flag is an arch-signifier, a mother of all signifiers, proliferator of infinite chains of tropes and their referents. Instead of dredging you through a what-and-how this flag might mean, I present an anecdote, as told to me by Rubén Ortiz Torres, about a theory class at CalArts, where Thom Andersen was explaining semiotics using, but of course, one of Jasper Johns’s famous encaustic paintings of a/the flag. Following Andersen’s lecture about the signifier, signified, sound-image, referent, and so on, a student raised his hand to ask: “But … but … but what does it mean?”

Andersen paused, turned to stare at the projected image for quite a long moment, and then turned back to solemnly state: “It’s about repression.”

Indeed. Rubén and I burst out laughing. No additional words necessary to share meaning. No need to explain the joke. A collective.

Let me kill it for you now. The subversive innocence of “But what does it mean?” begs resolution from an artwork that is coldly concerned with “how” a work makes meaning, with the principle of meaning and not what its referent is or means. It exposes our need for closure, our desire for static meaning beyond structural analysis. The second part of the joke is that at the end of all the critical distance afforded by an analytic perspective its impossibility lies. Johns’s flight from subjectivity was always an illusion. For Johns, rendering the semiotics of pictorial signification was rooted in the suppression of sexuality. It took another structuralist to see it.

The third layer of the joke is the suspicion, always extant, that the speaker is referencing none other than his own work. “It’s about repression” perhaps refers to the entire legacy of semiotics and art. Next comes the anxiety that this kind of observation spreads like a virus and is also soon to implicate us (which it does even beforehand, since clearly “us,” refers to the “we” who love semiotics and art), in the paranoid sense that we are always being observed, and that the observer sees something we cannot. This sense is not wrong.

The Geffen, like many other display and commercial spaces that embody nineteenth-century reform legacies, has a mezzanine. In his foundational work on the museum, Tony Bennett has shown the ideology behind the architectural integration of the open second story into the plan of the building. That publics can view their others down below helps them internalize a sense of surveillance and encourages the self-policing of behavior.1 Pope.L pushes this operation with Snow Crawl (1992–2001/15), a wooden ramp that brings the viewer well above the mezzanine, underscoring the sense of both ascendance and oversight. With a final additional step, the viewer peeks into a kaleidoscopic view documenting one of Pope.L’s well-known durational and episodic performances based on the act of crawling, a voluntary lowering of the upright human posture with all the physical and symbolic implications carried by this act. We have ascended quite a bit to overlook a mirrored cylinder where pictures of a man crawling through the snow in a Superman’s costume, get mechanically rearranged by a kaleidoscopic refraction mechanism, turning him into a pattern.

Installation view of William Pope.L: Trinket, March 20–June 28, 2015, at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. In foreground: William Pope.L, Snow Crawl, 1992–2001/2015; wood, mirror, TV, and video; 114 × 206 × 110½ inches; video duration: 7:42. On walls: William Pope.L, Circa, 2015; oil on linen; 24 parts, 27 × 18 inches each. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Around the walls, Circa (2015), a series of oil paintings on linen, extends Pope.L’s inquiries with his ongoing twenty-year practice of Skin Set Drawings, where he uses materials and words that represent color. Playing on the semiotic and associative meanings of visual phenomena, these paintings show how human racial relations are bound to codes of signification and tease out the absurdities of that connection. Each one is painted in fuchsia, spelling “Fuchsia” and an associated word also ending with an “a,” such as “Fuchsia Ebola” and “Fuchsia Abracadabra.” The viscosity and behavior of the impasto gestures bring the visual and textual character of this color closer to our viscera. Textual meaning comes in and out of communication, as the intense gesture sometimes makes the words illegible, disappearing, like truth, under the layer of representation. The series also has another gap in its syntax, a missing canvas that appears downstairs across the main floor, drawing our eye to the other side of the vast room, the flag, and the operation of the mezzanine between the semantic and the somatic.

From the perpendicular side of the entresol we overlook a vast roomful of rows of tables on top of which painted onions, in various stages of ripeness from sprouting to rotting, are arranged, mostly in a grid. Polis or the Garden or Human Nature in Action (1998/2015) also appears here and there in the nooks and crannies of the building, inside other installations, sometimes tucked away in corners or crevices. Polis, meaning the ancient Greek city-state and also citizenship, locates the origin of our modern nations in that image of the ideal society. But the American Polis Garden is a far cry from governance aimed, as Plato describes in The Republic, to serve the common good. Seen to reference rows of uniformed citizens, the decaying onions are inevitably associated with the withering of our democracy. “I think there are cracks in the seams of what we are,” Pope.L explains. “There is a post- Vietnam malaise as the aspirations of the ’60s fell short in many ways… The ideals of our country have been tarnished by imperialistic moves.”2 Onions cause tears, but are also an antidote to tear gas, their pungent odor described by Gabriel García Márquez, in his The Autumn of the Patriarch (1975), to be emanating from the armpits of his decaying patriarch as a symbol of his oppression. Olfactory signification is so much more intrusive, so much less benign, than the visual.

Installation view of William Pope.L: Trinket, March 20–June 28, 2015, at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. In foreground: William Pope.L, Polis or the Garden or Human Nature in Action, 1998/2015; onions, paint, and 15 wood tables, 30 × 96 × 48 inches each. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

The whiff carries through the central hall; it now seems that the fluttering flag is trying to air it. I am reminded of the flare of emotions in response to a recent attempt by the University of California Irvine student council to ban flags from their common area. It brings to mind Einstein’s quip: “The flag is a symbol of the fact that man is still a herd animal,” which has been on my mind since seeing it on Renée Green’s banners in several of her installations. It explains this signifier’s power to promise coherence where there is none. The flag is not a symbol of patriotism, it is a symbol of each and every one of our primitive selves; inside the container of contemporary art, it is an image of ambivalence.

If anything, what unifies so many of us under the flag is a growing sense of disenfranchisement. Just as the recognition of climate change and the impending ecological disaster moved from fringe knowledge to mainstream understanding, so now the realization is unfolding that the United States is not a functioning democracy. As a study that emerged from an academic journal to the attention of the mainstream media claims:

Multivariate analysis indicates that economic elites and organized groups representing business interests have substantial independent impacts on U.S. government policy, while average citizens and mass-based interest groups have little or no independent influence. The results provide substantial support for theories of Economic-Elite Domination and for theories of Biased Pluralism, but not for theories of Majoritarian Electoral Democracy or Majoritarian Pluralism.3

The authors, Martin Gilens, Professor of Politics at Princeton University, and Benjamin I. Page, Professor of Decision Making at Northwestern University, conclude: “Americans do enjoy many features central to democratic governance, such as regular elections, freedom of speech and association, and a wide-spread (if still contested) franchise. But we believe that if policymaking is dominated by powerful business organizations and a small number of affluent Americans, then America’s claims to being a democratic society are seriously threatened.”4

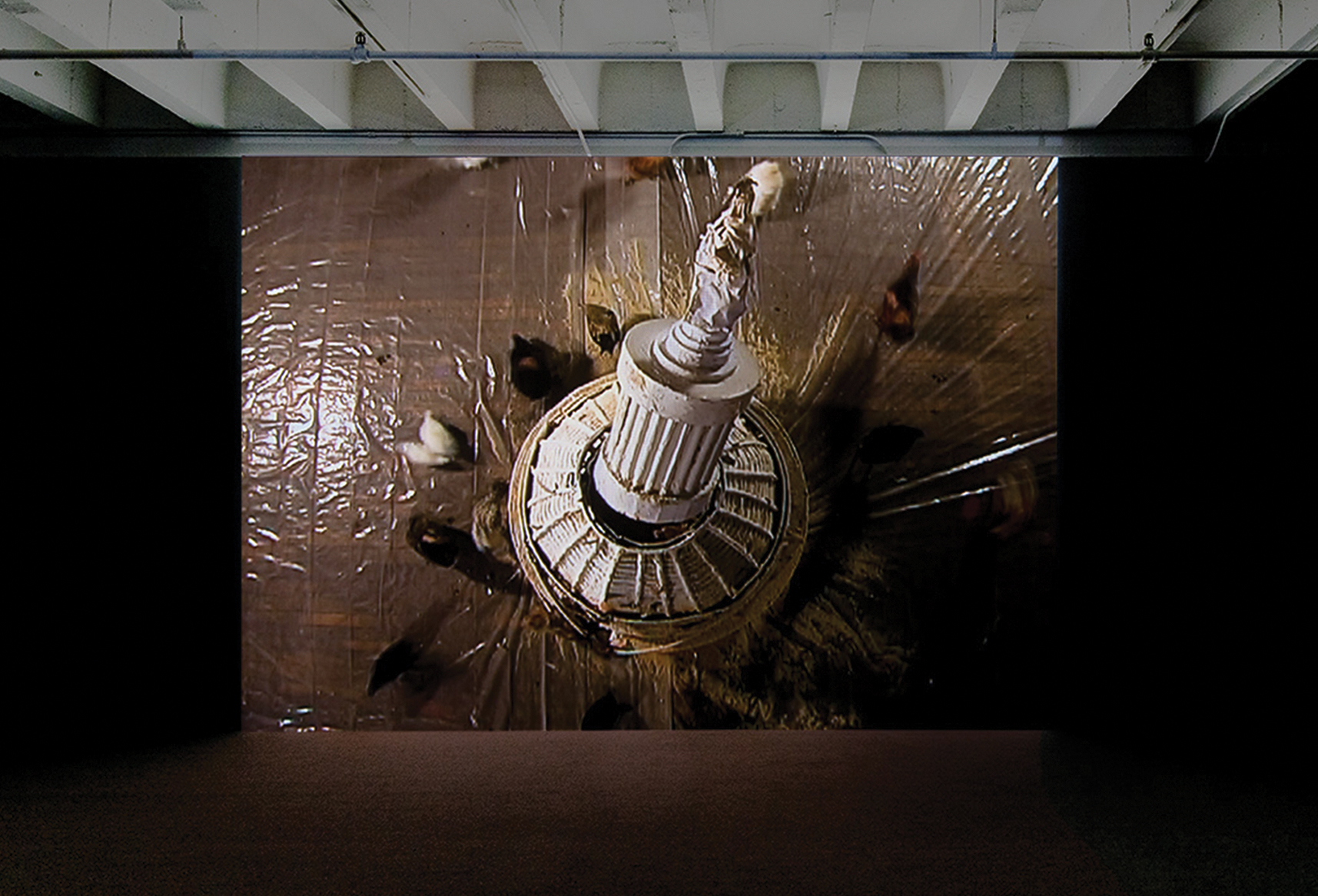

In and out of the exhibition’s sections, we have to confront our relation to the flag. Under the mezzanine, we enter another work where we are engulfed by one construct, while observing a set of several others. Small Cup (2008) refers to the cupola, a small dome, frequently at the top of a larger dome, on ceremonial buildings. It is the main character in a video that lies at the end of a series of rooms, where by the simplest means of plastic sheets and blue light Pope.L has effected a haunted atmosphere, a theatrical illusion bare to the eye that nevertheless has a physiological influence on us, exacerbated by the penetrating smell of onions positioned as directional signs. Made of cardboard, peanut butter, and seed, the small cup itself appears in a video, and is a habitat for chickens and goats to frolic and feed until the model collapses, an apocalyptic take on Hans Haacke’s 1960s biological systems (for example, Chickens Hatching from 1969). Commencing with a shot of a pastoral image on canvas, the metaphor could speak of past or future ruins, or, contrarily, of co-habitation and continuity through transformation, or of transformation through destruction. The video references several cinematic and theatrical vocabularies. Tracking shots mime the suspense of horror movies, walking us through the vast spaces of an industrial building, a narrow shot limiting our range of vision, creating a haunting sense that we are being followed. It is contrasted by a long zoom-out that, like a 1960s French New Wave film, reveals the camera-crew at work on the cupola habitat. As if by mistake, a brief cut has a Hummer driving through the frontal pictorial plane. Or one might even miss the effect as a close-up on a goat’s rising ribcage is animated into a swirl, highlighting the animal’s breath, which animates it, like us, like the flag, like all living beings tucked between this sequence of real and represented spaces, where reality itself is already rendered by a network of signs and sensations that produce one another.

Installation view of William Pope.L: Trinket, March 20–June 28, 2015, at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. William Pope.L, Small Cup, 2008. Video with color and sound; 12:52 minutes. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

A symbol of sovereignty, the cupola represents authority. Yet the collective staring at the flag knows that the object’s power to mesmerize can be collapsed at the flick of a switch. Nevertheless, it seems that the state is perpetually able to keep its population in check despite the apparent contradiction that it does not serve the wellbeing of its population.

Characterizing the distinction between Georg W. F. Hegel and Karl Marx’s respective concepts of contradiction, Louis Althusser specifies the capital-labor paradox in how ideological forms are the product of both their superstructure (state, religion, etc.), and their contemporaneous contexts (capitalist competition, imperialism). In other words, the system of indoctrination aims to ensure that the modes of production are sustained, that, for example, a working class is sustained, always available to reproduce itself (in other words, never to advance). It is not only life conditions that keep subjects in their designated place. Steeped in ideology, representation also works to produce attachments that result in subjects holding themselves down. Between Hegel’s and Marx’s work, both the method and the context have shifted so that a new concept of contradiction emerges in Althusser’s understanding of Marx: “Not just because the State can no longer be the ‘reality of the Idea,’ but also and primarily because it is systematically thought as an instrument of coercion in the service of the ruling, exploiting class.”5 These recognitions animated the spirit of the 1960s, whose ghost haunts the exhibition as a broken promise, lingering like a smell in the corridors of museums and universities, institutions built on the contradiction between their publics and their administration, which itself mitigates the deeper contradiction of nonprofit institutions mandated to serve the public and not the class interests of their philanthropic leadership.6

Staged on the campus of Tennessee State University, a historically black college, Reenactor (2012/2015), a 185-minute video where student-actors go about their lives wearing ill-fitting costumes of General Robert E. Lee, brings into relief the perverse desire that drives the elaborate practice of historical reenactments. The allegory summons a suppressed truth, where the horrors of the past live as fetish objects in the present. A conversation between Traveller, the Confederate General Lee’s famous horse, and the ghost of Lee’s slave, is spliced in, animated by puppets with a voiceover by Pope.L. The puppets speak about history and the negative space it takes to render it. Text slides inform the viewer who the two characters are and that “the space in between them is you.” It ropes me in, as if the flag has not implicated me already. The viewer is the negative space that gives history existence at the moment of its reception, that makes the characters legible, that sutures us into the meaning of the work in a core Duchampian gesture: the meaning is with the viewer at each instance of reception, meaning is embodied or it is not. Superimposed on a sequence roaming through the Southern landscape, a translucent stream of pouring fuchsia paint cuts like a drawn line. It recalls Circa, where words about color have double meanings and paint behaves like material. In the background now a close-up crops the sign “No Trespassing.” It connects the visceral connotation of the fuchsia material and verbal signifier to the human body, now verbally warned—threatened—by the authoritative status of private property: “No Trespassing.”

Installation view of William Pope.L: Trinket, March 20–June 28, 2015, at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. William Pope.L, Reenactor, 2012/2015; installation and video with color and sound, 185 min./100 days continuous; dimensions variable. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

I see the flag again before I float into a room at the invitation of air movement. The walls in and out are gallery white, but the interior of the doorway is dark blue, like the frame of the small window at the other end through which the air blows, as if generated by the flapping flag. The air in fact emanates from one (or more) of the rooms that exhale this work, called Blind (2015). The additional rooms are built behind the blind wall, hidden from view. We know they are there. The warehouse ceiling stands tall, we can see the space above the rooms; it is verified by the light of a single bulb, which, with a humble gesture, captures a volume the size of the one that is out of our sight.

As I turn to leave the room, I see one more photograph, one of many that have been tucked away here and there, a moment of light between onions; I will end there in hope, but before that, the mud.

Installation views of William Pope.L: Trinket, March 20–June 28, 2015, at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. William Pope.L, Migrant, 2015; mixed media and live performance, dimensions variable. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Above the doorway a weak spotlight illuminates another element previously encountered. Letters directly on the wall spell qua qua. Perhaps their own unannounced work, perhaps part of Migrant (2015), maybe they are the voice of consciousness. Qua means “in the character or role of”; qua qua means something like “as as,” and is a character in Samuel Beckett’s obtuse novel How It Is (first published in French as Comment c’est in 1961), a voice the identity-less character hears. The novel can be seen as an allegory of a mind thinking its existence as beings crawl through a universe of mud. They meet, co-inhabit, and part.

Pope.L’s Migrant is a wood edifice resembling barrack bunks and hugging the angles of the Geffen’s back wall. Manholes are carved out in several spots, and an opening to the back rooms connects it to Blind (as does its color scheme). Cage-like bars secure and frame the performers who periodically animate Migrant. Emerging from the back blindfolded, in cocoon-like costumes, they crawl around the work, interact and co-inhabit, for three hours. The phenomenological contradiction of the mind thinking itself is enacted in how the performers feel their way through the object, or their encounters with one another, without which they have no point of reference. If the movement of the performers between the levels of the edifice echoes Trisha Brown’s Floor of the Forest (1970), it is as if the motion in Migrant continues away from Brown’s vibrant colors and into the gray tones of mud that would be underneath, slow moving and hallucinatory, an acid hangover in the wake of the 1960s dream. “What to do?” Pope.L is quoted on the wall label, “if you move in a world without mend.” Migrants are people who move for the prospect of a better life. In a world without mend one moves forward because there is no other choice.

Installation view of William Pope.L: Trinket, March 20–June 28, 2015, at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. William Pope.L, Blind, 2015; mixed media, dimensions variable. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

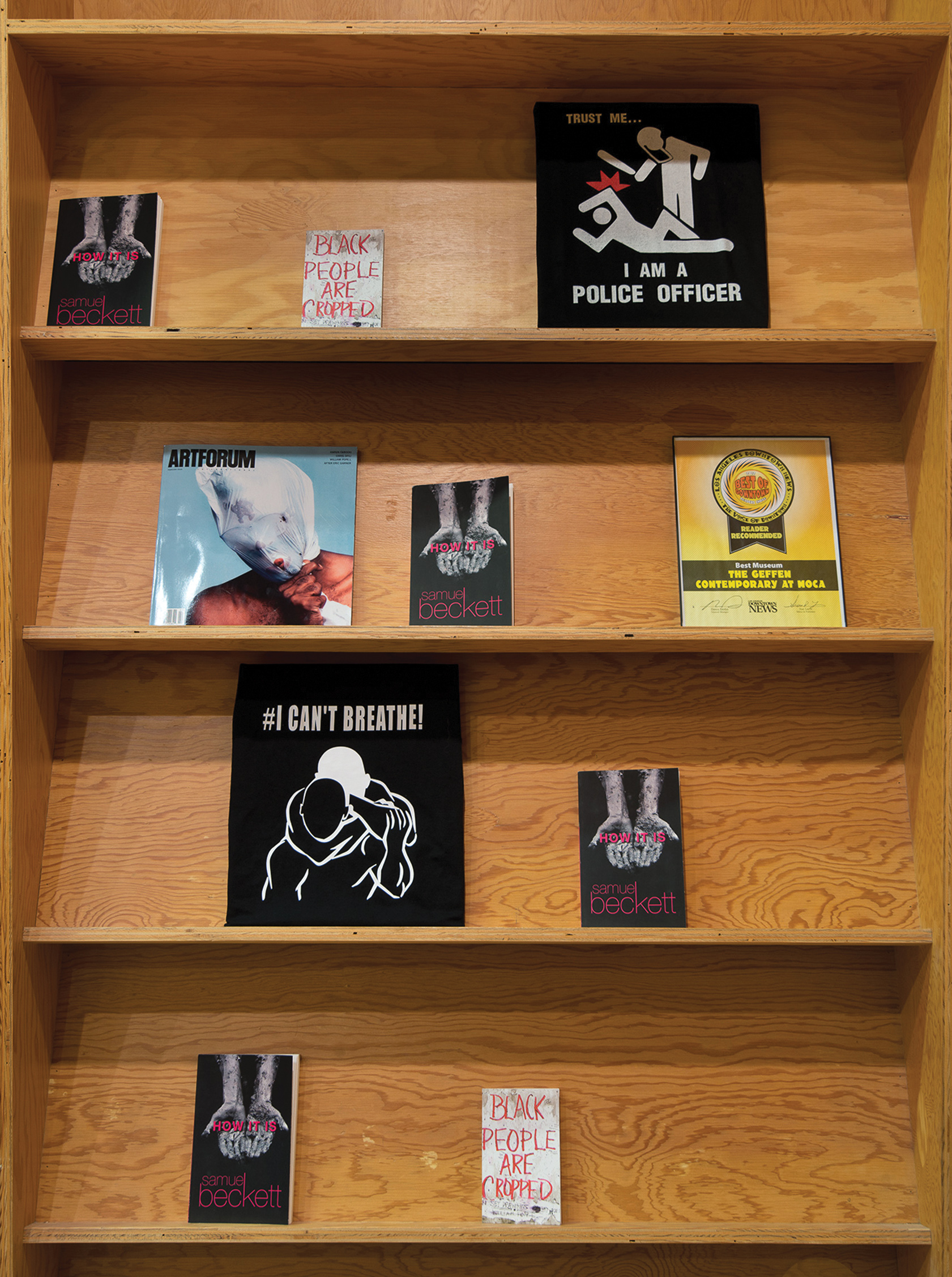

The current 50-star version of the United States flag was adopted on July 4, 1960. The flag at the Geffen has 51. Asked by curator Bennett Simpson about the extra star, Pope.L answered: “For you.” “You” is a shifter, a signifier that gains its meaning from its referent, rather than the other way around. Within the context of Trinket, “you” is anyone who stands under that banner. Speaking of trinkets, not to be missed are the t-shirts inserted on the reading-room shelves, on which recent murders of black men by the police have been consolidated as commemorative logos and clips of political speech—the body as message board.7

Installation view of William Pope.L: Trinket, March 20–June 28, 2015, at The Geffen Contemporary at MOCA. Courtesy The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

Every time I left the show, three times so far, it felt like I was carrying away the exhibition inside my head as a model, that the elements revolve around each other like a constellation, shifts in scale pulling me into and out of the picture—from the experience into the meta-space of reflection, suspended between contradictory poles. Usually, one goes from the map to the experience. Here I went from the experience to its map.

So where do we go from here? One could follow, like small signs, the thirty-four 5 x 7-inch photographs that make up Looking for the Sun (2015), humble objects looking obliquely from Pope.L’s perspective in the direction of his young son, who is barely seen or not at all. This is the legacy, the future, the real stake the artist has in all of this, and with him us, we follow just behind, barely keeping up, just arriving or having just missed the moment. May he use the image of his son? The artist shares his ethical dilemma in the brochure. We share it too under the same sun.

Dr. Nizan Shaked is Associate Professor of Contemporary Art History, Museum and Curatorial Studies at California State University, Long Beach. Her book The Synthetic Proposition: Conceptualism and the Political Referent in Contemporary Art is forthcoming from Manchester University Press for the series Rethinking Art’s Histories (edited by Amelia Jones and Marsha Meskimmon).