“The uncanny valley” is a concept widely known among animators, artists, and other creators of likenesses. Masahiro Mori coined the expression in his 1970 thesis and accompanying graph, which indicated that humanoid robots become less convincingly “alive” the closer their appearances track actual humans, because the increased verisimilitude actually forces the incongruities between artificial and biological life to the surface, eliciting a strange and disturbing affect.1 This distance, which has been skillfully manipulated by animators and roboticists, visually telegraphs a feeling of alienation that Sigmund Freud, citing Ernst Jentsch, popularized as unheimlich. Translated from the German as uncanny, it connotes a feeling of death-in-life and is the term upon which Mori’s concept was based. Artists of the early twentieth century, such as Surrealist photographer Hans Bellmer, took the uncanny phenomenon to erotic (for some) extremes in their work, while Disney/Pixar artists have long used Mori’s graph as a barometer to make everything from cockroaches to sea monsters read as “cute” to the average viewer.

Freud’s uncanny is a sense of dread, prompted by disassociation, that is produced in the mind of the living when confronted with an animated, but not convincingly alive, likeness of human embodiment.2 It is an incongruous reminder of mortality that rests within the familiar context of the life-world. The uncanny alienates us from ourselves because it suggests that the mechanisms of human existence could be fulfilled in our absence, that we could be compelled to fulfill them eternally without the respite promised by belief in immortal animus or higher consciousness. Even the cognitive science of the uncanny involves automation, in the sense that the mirror neurons in our brains are not consciously activated to perceive a stimulus as human-like in a manner that provokes the uncanny response.3 Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI at the de Young Museum evoked this response from several directions with artworks that processed and presented an overwhelming quantity of data, that described a ubiquitous and pervasive network of digitized surveillance in our midst, and that questioned existing definitions and expectations of the category of human and its relationship to political representation, economic prosperity, and civil rights.

As artificial intelligence technologies increasingly function through the aggregation of human impulses, preferences, and experiences, the technological uncanny that the exhibition describes is characterized by human-like systems whose affective reactions and word choices seem disproportionate to input stimulus. This reflects the aggregate amplification of individual preferences by nonhuman systems, often complex, that are information-driven and produce an output we can characterize as “intelligent” processing of data, but do not prioritize human expectations of legibility or usefulness. In many works, there is a sense that the (automated) speaker does not comprehend what is being said, which is compounded by the viewer’s commensurate but different inability to understand it. This ethic of not-knowing is potentially a constructive counterforce to the technological boosterism of the Bay Area tech culture, which is also well represented here.

Stephanie Dinkins, Conversations with Bina48: 7, 6, 5, 2, 2014-present. Installation view, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI, de Young Museum, San Francisco, February 22, 2020-June 27, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Photo: Randy Dodson.

Curator Claudia Schmuckli has organized the monumental exhibition around contemplation of the uncanny as an aesthetic that proliferates in the online world. Our experience of the phenomenon, she writes in the exhibition catalogue, is primarily visual, and the exhibition robustly fulfills this expectation.4 The first thing I noticed was the abundance of eye candy. In the bold black-and-white flowchart graphics of Martine Syms’s installation, colorful data-generated moving image works by Zach Blas and Ian Cheng, LGBTQI+ icon Tessa Thompson playing host in Lynn Hershman Leeson’s work, and dazzling animations of a Sinofuturist world by Lawrence Lek, we are shown a vision of future-oriented identity discourse that is shiny and well-resourced, with high production values. The works of Trevor Paglen and Hito Steyerl describe a second aesthetic at play, the data aesthetic of archives, hashtags, and evidence photos. An eco-aesthetic is present here as well, as manifested in Pierre Huyghe’s work with bees and Agnieszka Kurant’s work with termites, the inclusion of which gestures toward biological models for collective intelligence from the insect world. These modes of inquiry reflect trends in AI data collection and processing, such as biometric measurements, linguistic taxonomies, and networked ecosystems. The exhibition is striking in its generous layout, which affords each participating artist an area comparable to a biennial exhibition and is far more spacious than the average group show.

Propelled by the exhibition’s fascination with and seeming acceptance of systems thinking as a logic that can regulate all forms of interaction, I was struck by the sense that these technologies are being normalized while they retain the potential to reorganize society in highly destructive, biased, and discriminatory ways. As I moved through the galleries, I was presented with artworks processing information on a computerized scale that was more than a human’s perceptual and cognitive capabilities could ever meaningfully take in. These experiences caused me to question whether I, a human with a body and neurological cognitive capabilities, was the intended audience for the artworks on display, or if I might be sharing that privilege with artificially intelligent systems, either now or in the future. Of late, Silicon Valley has developed an uncanny affect, from the dead-eyed photos of Mark Zuckerberg and Jeff Bezos that circulate online to the weird targeted browser ads that promise imaginary wealth with real status attached: “Become a digital landlord of a virtual property mapped to the real-world addresses based on Blockchain technology. Enter Now to a New Metaverse!” Slogans like this one reflect a technofuturist desire to synthesize a new virtual universe of existence, a hyperlayer that absorbs the physical-biological world into an augmented digital reality. The Metaverse economy is oriented toward AI actors, either in lieu of or in conjunction with organic sentient beings.

Hito Steyerl, The City of Broken Windows, 2018. Installation view, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI, de Young Museum, San Francisco, February 22, 2020-June 27, 2021. Courtesy of the artist; the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Esther Schipper, Berlin. Photo: Randy Dodson.

A lot has changed in forty years of robotics, and inevitably, critiques have emerged of Mori’s “uncanny valley” theory. One comes from David Hanson and his team at Hanson Robotics, one of a few current creators of AI-powered humanoid robots. They write that human aversion to human-like replicas is a myth and cite as evidence the myriad examples of artistic figuration that depict the human form. Their emphasis is on expression, the thousands of minute movements that we make with our faces as we are speaking, thinking, and communicating nonverbally with others. Perhaps these creations will trigger an uncanny aversion in certain people, but these roboticists have found that people also respond positively to humanlike robots. While Mori’s theory is anchored in the premise that lifelike realism in robotics is beyond our scientific capacity to achieve without provoking the distancing impulse of the uncanny, Hanson and team refute this assumption. Using the art history tradition of Mannerism—selective exaggeration of certain figurative traits to serve the purposes of expression—as their basis, they claim that people can be taught to accept what was previously strange to them. Mannerism emerged from the late Italian Renaissance to inform aspects of the Baroque and reemerged in contemporary hyperrealist figuration by sculptors Ron Mueck and Patricia Piccinini, and painters John Currin and Lisa Yuskavage. The style is associated with pleasure, sexuality, and great wealth, often representing women as pleasing ornaments and men as gentlemanly explorers. Artifice and stylization are its stock in trade.6 Hanson creations, such as Bina48 (discussed later in this essay), are rigged with ever more complex facial armatures that allow for minute gestures of expression intended to read as engaged, enthusiastic, and vital. The intention is to emulate humanlike characteristics in a way that reassures humans about the robots’ affability, but not necessarily to convince anyone that they are living humans.

Those whom we do not recognize as racially and culturally like us may not figure within our preconceived expectations of the human, as Sylvia Wynter has noted in her essay “No Humans Involved: An Open Letter to My Colleagues” which declares Black Americans an uncanny, other-than-human presence in US society and law.7 As those who do not meet the white cisgender heteropatriarchal mold can be deemed incompatible with the ontological classification of “human” and thereby assigned to the class of anomalies whose behavior must be patrolled and whose appearance must be minimized, the same occurs with AI. Information that does not correspond to algorithmic predictions is cast as anomalous, poor-quality data. Steyerl, whose The City of Broken Windows (2018) is included in Uncanny Valley, has described how consultants at Booz Allen Hamilton misread demographic data about luxury hotel guests because the idea of wealthy teenage Arabs deviated from the consultants’ worldview of the region as underprivileged.8 Bias in AI is both about what gets left in (racial slurs, misogyny, visual discrimination) and what gets left out (points of view that deviate from the “norm”). Without actively employing people to design, review, and curate data sets, the algorithm will circulate and amplify those biases in perpetuity, oblivious to any real world outcomes.

Ian Cheng, BOB (Bag of Beliefs), 2018-19. Installation view, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI, de Young Museum, San Francisco, February 22, 2020-June 27, 2021. Courtesy of the artist; Gladstone Gallery, New York; and Pilar Corrias, London. Photo: Gary Sexton.

Uncanny Valley incorporates several works anchored in human or animal biological characteristics, such as heart rate and skin color. The first few works I encountered circumvented questions of wrongness or how the uncanny applies to humans deemed Other by proposing we consider alien physiognomies and unfamiliar states of consciousness. This is in line with how science fiction often maintains the structures of real-world oppression while abstracting the power dynamics by fictionalizing racial and cultural narratives. Attributing human-like characteristics to a non-human, synthetic biology, Ian Cheng’s BOB (Bag of Beliefs) (2018–19) proposes that the characteristics of biological liveness can be represented by abstract biometrics, such as statistics and measurements. BOB (Bag of Beliefs) is a grid of eighteen screens on which a digital organism, BOB, lives out its daily existence in a beige, non-linear landscape. BOB appears as a long, misshapen, stringlike creature and is described by the artist as an “artificial lifeform” and “a chimeric branching serpent.”9 For this viewer, the tangle of spikes, faces, and eyes never resolved into a single, unified form. As such, it helped to understand the creature as a system more than an organism. BOB illustrates a transhumanist conception of the human as an outdated, meat-based technology that we could systematize and quantify ourselves out of into new, viable systems of living and interacting in the virtual world. Yet the human body itself is a system, powered by bacteria and other microbes that are deeply integrated into both the physical and the neurological environments that generate and house our consciousness.

BOB’s physiognomy is decidedly weird and nothing like a human’s. But for the racist, as described in the literature of HP Lovecraft, the appearance of a person of unknown race or their cultural production provokes a similarly estranged response. Mark Fisher equates this sensation in Lovecraft not with abjection or rejection but rather with fascination, which he describes as “a form of Lacanian jouissance” in which pain and pleasure are enmeshed.10 Fisher distinguishes between the unheimlich, the “weird,” and the “eerie” as such: the unheimlich connotes the strange within the familiar, while the weird is out of place, and the eerie is an incomprehensible absence. BOB in this configuration is so unfamiliar as to be out of place in our world, though it fits comfortably within its own. Though not exactly uncanny, it evokes wrongness, a promise of an order different from the one we take for granted.

BOB’s physique is uncanny—simultaneously soft and hard, kawaii and sinister—but not everything about its experience is unfamiliar.11 Observers can watch BOB respond to conditions within its simulated environment, statistics for which appear on a smaller screen. BOB eats, avoids predators, explores, and worships. “Metabolism” is governed by a set of metrics: energy, rest, bladder, and stomach, each represented as a “health bar” as would indicate a video game player’s remaining strength or hit points. It’s not hard to see a parallel between Cheng’s fabricated life form and our own quantified selves, tracking BMI and sleep cycles to optimize our bodies for capitalist production. Even worship has now been digitized: a Google app, Qibla Finder, uses augmented reality to point observant and technologically savvy Muslims toward Mecca from points around the globe at appropriate prayer times.

Zach Blas, The Doors, 2019. Installation view, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI, de Young Museum, San Francisco, February 22, 2020-June 27, 2021. Courtesy of the artist. Photo: Gary Sexton.

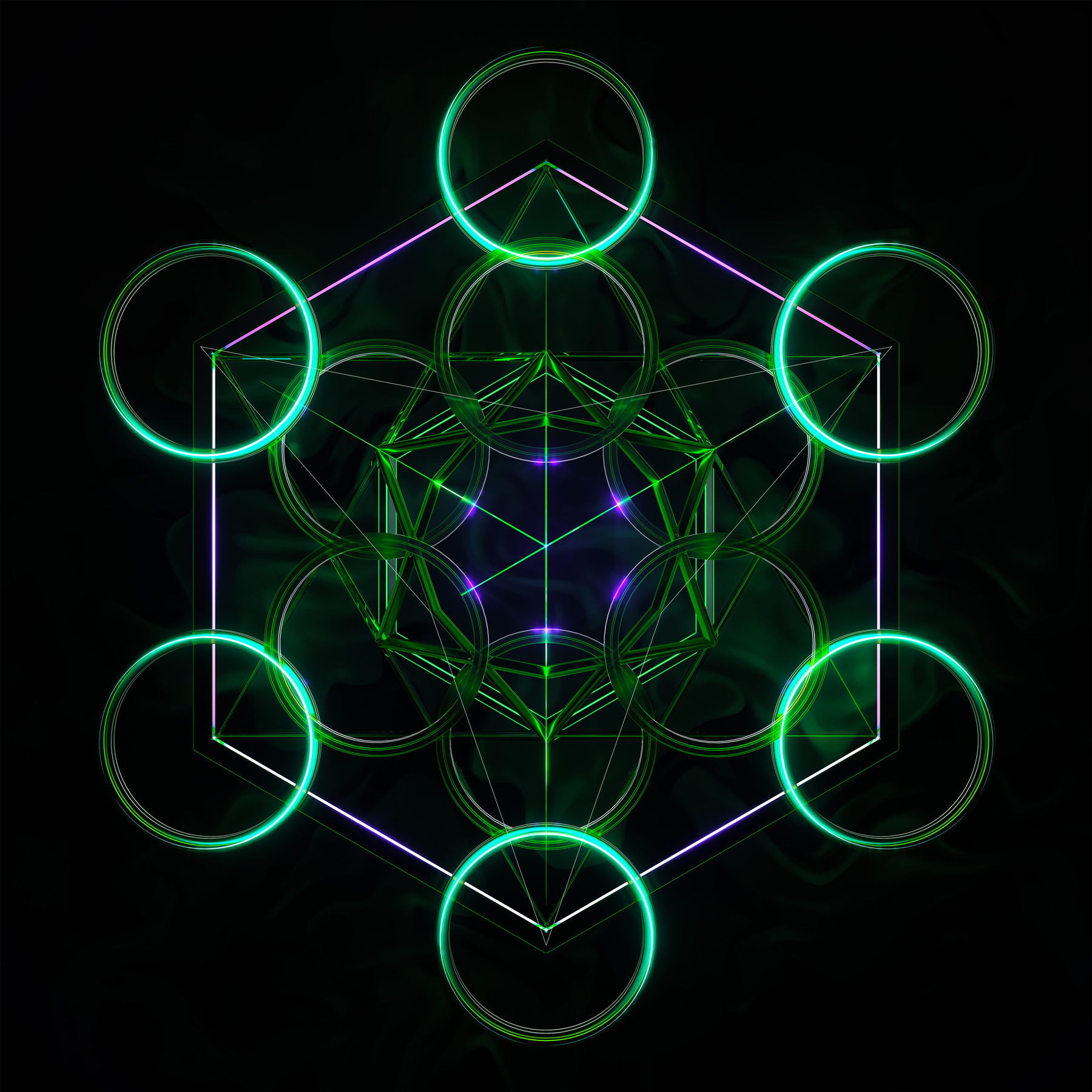

Blas’s installation The Doors (2019) brings this metaphysical aesthetic to the human body. Drawing on the titular concept from Aldous Huxley’s 1954 hallucination narrative, The Doors of Perception, Blas considers the evangelical aspects of technophilic culture that stem from its emergence out of the broader 1960s counterculture and its New Age philosophy. Nootropic or “smart drugs,” used by many in Silicon Valley to “self-optimize,” sit at the center of the installation in a hexagonal vitrine. An intricate pattern, labeled as the “Metatron’s Cube” of sacred geometry, radiates across the floor in vector-cut Astroturf. The icon is formed by thirteen circles organized in a centripetal pattern, connected on the perimeter by a hexagon and from within by two intersecting triangles. According to the artist, this image, which has Biblical overtones, is associated with the branding of psychedelics, including nootropics.12 The drugs include “stacks” of edible supplements tailored to a user’s goals and “microdoses” or minute quantities of hallucinogens, such as LSD and psilocybin. These drugs are commonly thought to interfere with logical thought, however microdosers consume small amounts with the intention of focusing rather than distracting the mind. Huxley’s ambition of using hallucinogens to shake free of complacency is now being reconstructed into “self-optimization” doctrine in the service of unquestioned economic productivity.

Zach Blas, The Doors. Video still. Six-channel HD video installation with eight-channel surround sound 41:26 min. Courtesy of the artist.

Blas has trained a neural network to generate poetry from a data set found in the corporate-branding literature for these smart drugs and the collected works of Jim Morrison. The resulting recitation is accompanied by animations of extinct lizards on six monitors arranged in a circle. The lizards, “Barbaturex morrisoni,” are so named in the scientific literature “in honor of the late rock singer.” Live plants and recorded sounds collected from Myanmar, Hawaii, the Mojave Desert, and the Bay Area mix with forms and sounds from “an imagined plastic garden.” The AI-generated video imagery is trained on counterculture visuals and art, biological elements, sacred geometries, and glass in architectural and deconstructed configurations. Sound is produced from ambient sounds, beats, and music by The Doors. Much like the psychedelic light shows that the work seeks to emulate, the effect can be overwhelming. The work engages Fisher’s architecture of alienation on all three fronts: weird, in the sense that much of the imagery seems random and arbitrary; eerie, in that the Indigenous cultures whose treatments and rituals inform these contemporary visioning practices are nowhere to be seen; and uncanny, in that the psychedelic aesthetics are so deeply familiar to our shared conceptions of “counterculture.” Sensory overload defeated me after some ten minutes in the space, dampening the mind-opening effects Blas references. Artificial intelligences generally do not experience sensory overload. I wondered whether the AI was better suited to have its consciousness expanded by this method than my puny human brain.

For viewers, Uncanny Valley’s visions of AI seem to operate at a massive scale because, from a human perspective, it is difficult to make sense of the volume of information being presented. From Blas’s work to installations by Syms, Christopher Kulendran Thomas, Leeson, and Forensic Architecture, more information is being generated than a person’s perceptual and cognitive capabilities can ever meaningfully take in, let alone use. The subdued presence of San Francisco’s extreme wealth is also apparent at the de Young, and not only in the lofty gallery ceilings adorned with the names of donors to the museum’s Herzog and de Meuron building (the rise of which paralleled the city’s tech industry boom).13 Unlike these artworks, whose data sets are in fact relatively small and parsable, artificial intelligence algorithms such as those powered by corporations like Google and Facebook tend to operate at a truly massive (and massively expensive) scale. Another uncanny aesthetic is at play, that of the billionaire class who represents aggregate wealth and aggregate influence invested in a few extremely powerful individuals.

Stephanie Dinkins, Conversations with Bina48: 7, 6, 5, 2, 2014-present. Video still. Four-channel video, 4 min. Courtesy of the artist.

Stephanie Dinkins’s Conversations with Bina48 (2014–present) highlights these dynamics. Bina48 is an AI-powered robot financed and owned by multimillionaire Sirius XM founder Martine Rothblatt. Bina is a likeness of Rothblatt’s wife, Bina Aspen Rothblatt, and it is intended to transform the living woman’s consciousness into an eternal digital form. This personally funded vanity project might have had little interest for contemporary researchers if not for the fact that Bina is African American, as is her android likeness. In these conversations, which are presented as short video vignettes on monitors, Dinkins approaches Bina48 without guile. She is not a critic of AI systems, nor is she trying to “trap” the AI in a weak answer that will show its shortcomings, though this happens. Bina48’s evident lack of cognition prompted Dinkins to base another work, also in the show, on building her own data set for Black Americans at a more comprehensive yet human scale.

Dinkins’s Not the Only One (N’TOO) (2018) is the artist’s first attempt to create an original data set from interviews with multiple Black participants. The resulting conch-like shape, which is 3D-printed with reliefs of the faces of interview subjects, is both a sculpture and a smart device. As viewers put their faces close and address the AI, the sculpture tells stories in the first person in response to their prompts. Dinkins is experimenting with “small AI,” in which a limited data set curated by one or more humans is supplied to the neural network to prompt generative responses. Former Google researcher Timnit Gebru was fired for advocating on behalf of smaller data sets that can be parsed by people, in contrast to the “big AI” methods used by her former employer and many other large data corporations. Small AI is an equity issue, as Gebru’s suppressed report on Google’s natural language algorithms makes clear.14 Massive automated neural networks rely on and reproduce polluted data that subsequently replaces verifiable fact as the basis for collectively defined “truth.” Algorithms running without human supervision will privilege the most widely available information, even when that information is factually incorrect, biased, or maliciously intended, as recent “fake news” cycles demonstrate. Still, even a culturally sensitive design for an AI data set cannot resolve the shortcomings of cognition that continue to plague artificially intelligent systems, more than a decade after Bina48’s creation.

Intriguingly, Uncanny Valley includes several works that are made, at least to some extent, without the need for people. Rather than computers, insects are the agents in sculptures by Huyghe and Kurant. Huyghe’s Exomind (Deep Water) (2017/20) is a reimagining of his prior work with bees, Untilled (Liegender Frauenakt) (2012), which debuted at Documenta 13 in Kassel’s Karlsaue Park and later featured in the artist’s 2015 Los Angeles County Museum of Art retrospective. Exomind is installed in the de Young sculpture garden, which is embedded within Golden Gate Park. The work is a cast-concrete figure of a squatting female nude whose head and upper torso have been consumed by a large beehive. Living bees populate the work, swarming the sculpture and buzzing around the surrounding flora.

Agnieszka Kurant, A.A.I, 2017. Installation view, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI, de Young Museum, San Francisco, February 22, 2020-June 27, 2021. Courtesy of the artist and Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Gary Sexton.

Kurant’s A.A.I. (2017) enlists termites and the biologists who study them. The artist fed gold, sand, and crystals to the insects, which then secreted luminous, jewel-colored mounds. The acronym A.A.I. refers to “artificial artificial intelligence,” which the catalogue entry explains is a term for human labor that is simultaneously specialized and devalued.15 Amazon’s Mechanical Turk is a platform for labor of this kind, and Kurant hired workers through the service to help her curate crowdsourced images of animals from the internet into meaningful artwork for her project Animal Internet (2018).16 Aggregating data is easy for the algorithm, but editing it into something that produces meaning for people remains an exclusively human endeavor. The competition we anticipate from AI and robots for jobs is as much a result of how little human intellectual labor is valued in the marketplace as it is an indicator that larger-than-human scale is becoming the norm for most commercial endeavors. The workplace is transcending the human, but the workers may not be invited to make the leap.

While swarm intelligence as a metaphor has long existed in the social sciences, as Schmuckli notes in her text on Huyghe’s work,17 artificial intelligence researchers treat bee and insect social structures as more than analogies. AI researchers use a model called a Swarm Intelligence Algorithm to distribute information-gathering and low-level decision-making throughout a large neural network. Such systems are informed by observing patterns of collective behavior in bees, ants, birds, fish, and other creatures. Each swarm consists of multiple “artificial agents” that explore and learn independently and share information. Flocking and foraging are animal behaviors that computer scientists have adapted to data mining. Even bacteria can be a model for algorithmic optimization.18 Rather than illustrate these applications, Huyghe’s and Kurant’s works resonate more strongly with a critique of human labor conditions as increasingly hivelike and inhumane.

Martine Syms, Threat Model and Mythiccbeing (detail), both works, 2018. Installation view, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI, de Young Museum, San Francisco, February 22, 2020-June 27, 2021. Courtesy of the artist; Bridget Donahue, New York; and Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Gary Sexton.

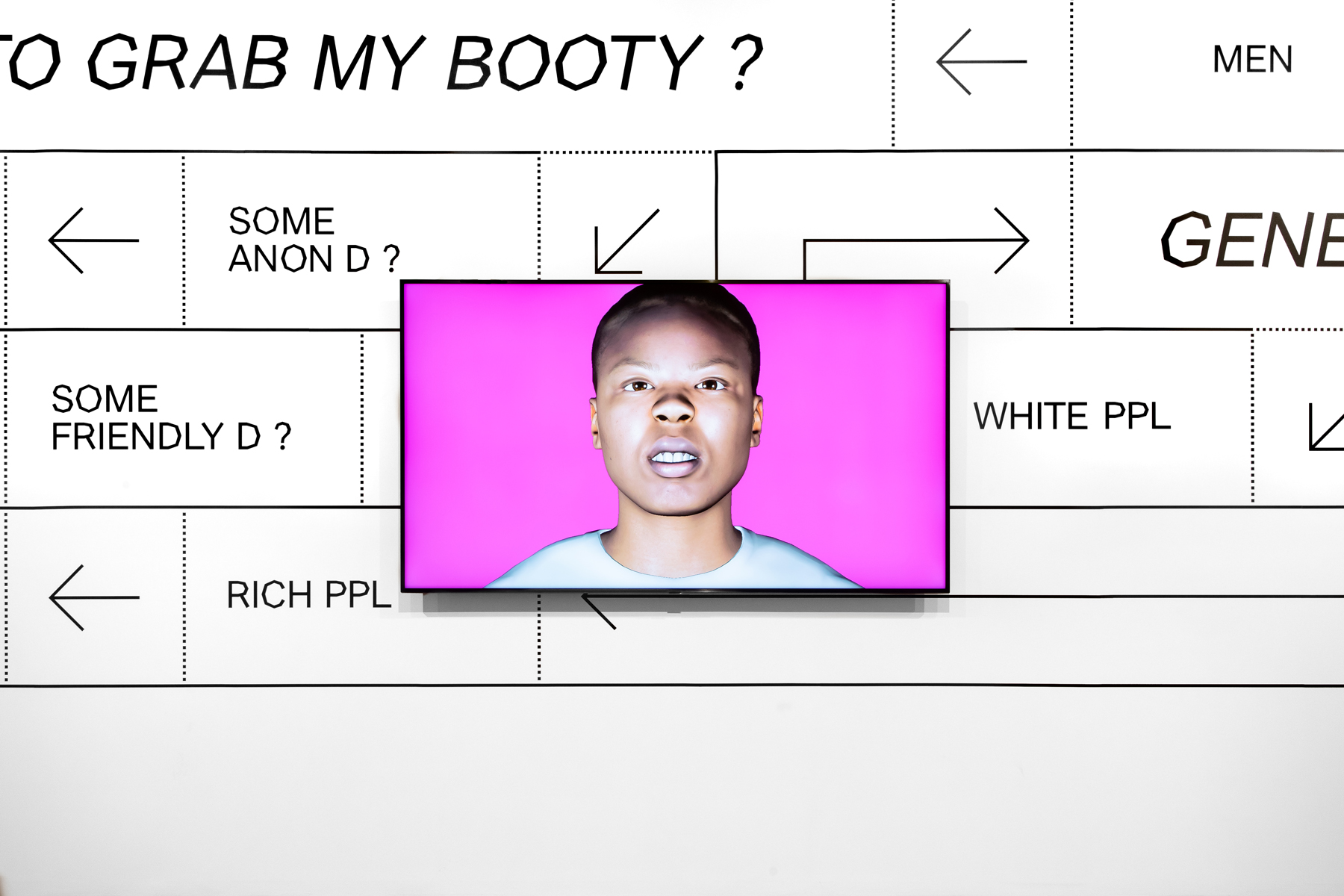

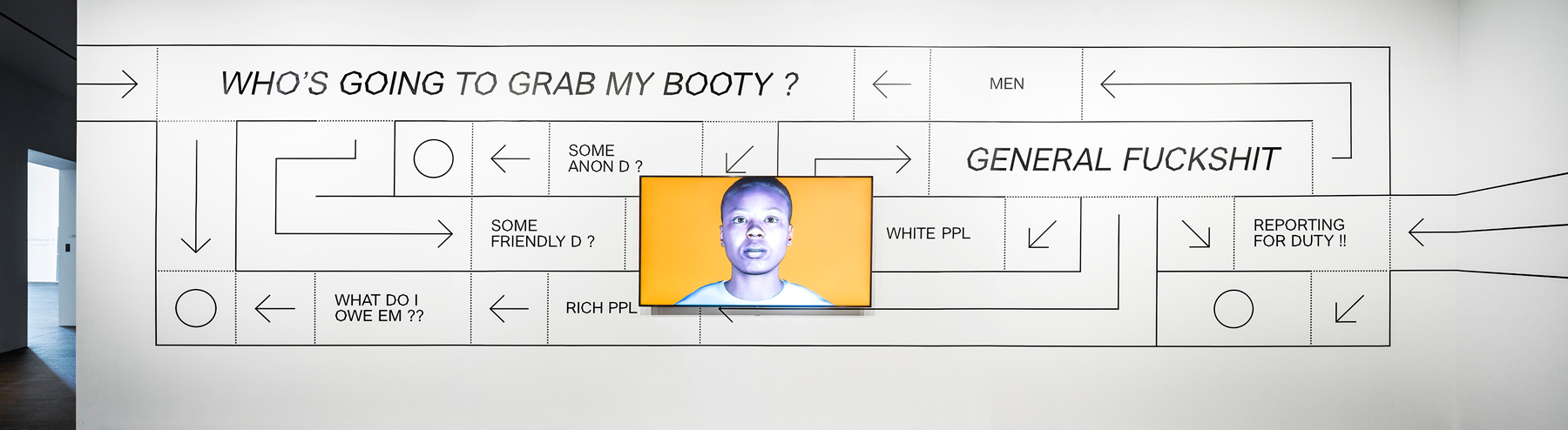

Martine Syms’s installation of Threat Model and Mythiccbeing (both 2018) talks back to that devaluation, which is felt most harshly among those whose bodies and experiences are already determined to be anomalous to the mainstream. Mythiccbeing is a riff on Adrian Piper’s performance project The Mythic Being (1973–75), in which the artist occupied a masculine, socially hostile persona that disrupted norms in public space. In videos of this work, Piper appears to be leveraging her Blackness to enhance the anxiety of those around her while her disguised feminine aspect subtly keeps the crowds around her from erupting into violence. That tension of aggression and servility is captured in Syms’s digital avatar, “Teeny.” Like the majority of digital assistants, Teeny is gendered female, foregrounding characteristics that viewers are assumed to read as submissive and helpful. Unlike the Black first-person characterizations in Dinkins’s work, Teeny speaks in AAVE (African American Vernacular English). She rejects respectability and instead expresses aggression and dismissiveness. Visitors are provided with a phone number that they can text to communicate with Teeny, along with a warning that she is likely to offend. The line seemed to have been disconnected when I tried it, but it’s also possible she couldn’t be bothered to respond.

Martine Syms, Threat Model and Mythiccbeing (detail), both works, 2018. Installation view, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI, de Young Museum, San Francisco, February 22, 2020-June 27, 2021. Courtesy of the artist; Bridget Donahue, New York; and Sadie Coles HQ, London. Photo: Gary Sexton.

At the de Young, the large-scale installation that Syms presented in her solo show at Sadie Coles HQ in 2018, with rear projection screen, floor decals, and four walls of vinyl text, has been cut down to a large wall with a section of the vinyl installation, titled Threat Model, and a modest monitor. The language, styled as a flowchart, describes a sexualized, transactional relationship between the artist as creator and the power structures of wealth and whiteness that govern their distribution and survival. Teeny, who had been larger than life, now appears at the scale of a televised talking head. If, as the exhibition text describes, Syms understands Teeny as an assistant “that didn’t want to serve you,”19 then the clapback here feels muffled by its placement, which suppresses the work’s aggressive emotional tenor. To return to Sylvia Wynter’s terminology, Teeny represents the digital continuation of Black experience as a “captive population” (per James Baldwin) or perpetual servant class structured intrinsically within the hierarchies of the social order. According to Wynter, expressions of defiance from Black creators are critically restrained by the assertion of a normative aesthetic order, an argument that plays out spatially in the experience of Syms’s work at the de Young.

Forensic Architecture, Triple-Chaser, 2019. Video still. 10:35 min. Courtesy of the artist and Praxis films.

The question of who is and is not admissible into the category of “human,” who is given rights and privileges, who is treated as disposable, and how wealth informs that distinction, drives Forensic Architecture’s Triple Chaser (2018) and Model Zoo (2020). The collective, founded by Eyal Weizman, investigates how the global 1% is funded by investment in international conflicts. Forensic Architecture works collaboratively with human rights organizations and activist groups to expose wrongdoing associated with trusted social institutions such as museums and nation-states. Warren G. Kanders, former vice chair of the Whitney Museum of American Art’s board of directors, is a pivotal figure in Triple Chaser, which debuted at the 2019 Whitney Biennial.20 Kanders’s financial investment in Safariland, a company that manufactures tear gas canisters that have been used by Israeli forces against Palestinian protestors and by US Border Patrol agents against migrants trying to enter the United States from Mexico, is the subject of the work. The underlying question was, does the Whitney (or any museum) view the people of occupied Palestine or undocumented immigrants to the United States as equally “human” to a captain of industry such as Kanders, or an artist/architect such as Weizman?

To create Model Zoo, Forensic Architecture used a machine-learning classifier to examine documentation from conflict sites, using pattern recognition methods developed while investigating Safariland subsidiary Defense Technology’s widely used Triple Chaser smoke grenade to identify where they have been deployed in combat or conflict zones. A video scans through the limited documentary evidence they found showing canisters to support their investigations. To address this shortage of visual evidence, they worked with activists in the field to collect more examples of the canisters for the data set so that the algorithm could better interpret partial images of canisters into confirmed matches. These canisters are exhibited in a sculptural installation that employs algorithm-driven CGI modeling software to replicate the prototypes of spent tear gas canisters used in Hong Kong, Syria, Chile, and other sites of regional conflicts involving civilian demonstrators. The 3D-modeled animated and 3D-printed physical objects warp, erode, and contract in a manner similar to how the actual objects might deform in physical space. Appearing like an animator’s library of background characters, the model zoo of tear gas canisters is an archive of potential forms that an algorithm can learn to detect in future evidentiary images of extralegal combat.

Forensic Architecture, Model Zoo: Introspecting the Algorithm, 2020. Installation view, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI, de Young Museum, San Francisco, February 22, 2020-June 27, 2021. Courtesy of the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Photo: Randy Dodson.

To borrow language from Judith Butler’s discussion of the optics of pro- Palestinian politics, Forensic Architecture’s investigations trouble our preconditions of whose lives are “injurable,”21 deserving to be grieved when lost, and who is collateral damage for more powerful actors whose experiences are acknowledged and commemorated in history books and museums. The physical archive of spent gas canisters are effigies for the absent archive that would tell the stories of everyone who has been on the receiving end of their blast. The museum as a physical, political, and economic entity, whether the Whitney or the de Young, is characteristically focused on the stories of the victors and their architectures of conquest. Architectures of destruction are rarely found except when approximated through documentary evidence, as in this work.

How effective are these admittedly arch and data-centric tactics in displacing abuses of power? Can information liberate a population? The limits of Forensic Architecture’s approach can be described by integrating two disparate modes of analysis, that of cybernetics and that of critical race theory. Using terminology coined by Norbert Wiener, researchers Francis Heylighen and Cliff Joslyn describe how AI researchers apply first-order cybernetics, or models that emulate and predict systems, and second-order cybernetics, wherein systems become autonomous through improved cognition and deviate from the models that first-order cybernetic researchers create. “Such an engineer, scientist, or ‘first-order’ cyberneticist, will study a system as if it were a passive, objectively given ‘thing,’ that can be freely observed, manipulated, and taken apart. A second-order cyberneticist working with an organism or social system, on the other hand, recognizes that system as an agent in its own right, interacting with another agent, the observer.”22 First-order cyberneticists, they caution, can mistake the model for the system or the facsimile for the whole, treating the whole system as an inanimate object of ingenious human design. Second-order cybernetics is driven by researchers’ awareness of their own subjectivity, what Donna Haraway calls “situated knowledges”23 that might counter implicit bias but which, Heylighen and Joslyn argue, can venture too far into philosophy and literature, straying from the mathematics that dictate what is actually possible.

Wynter’s concept of “Aesthetic 1”and “Aesthetic 2” mirrors this first- and second-order distinction. Aesthetic 1 is a unitary aesthetic, anchored in rules and norms, predicated on fitness and order, presented to society as a vision of social cohesion. It is an aristocratic mode that emphasizes nostalgia and hierarchy. Aesthetic 2 is more accessible, being the way for people to transcend the “form of life” and elevate into the higher, third-order consciousness that differentiates us from the larger cross-species mass of second-order life forms. It is consumption-oriented and aspirational, a mode that Wynter argues is largely bourgeois in that it flattens human experience according to informed “taste” the same way Aesthetic 1 flattens experience according to established norms.24 To apply Heylighen and Joslyn’s analysis to Forensic Architecture, the project feels stuck in first-order understanding that privileges systemic models and CAD aesthetics. To apply Wynter’s logic, Forensic Architecture eschews the Aesthetic 1 of institutional norms, classical architectures, and colonial domination in favor of an Aesthetic 2 of “resistance” that assumes that collaborations with western NGOs to develop new technological methods is the best way to defend against state violence, without foregrounding Palestinian voices.

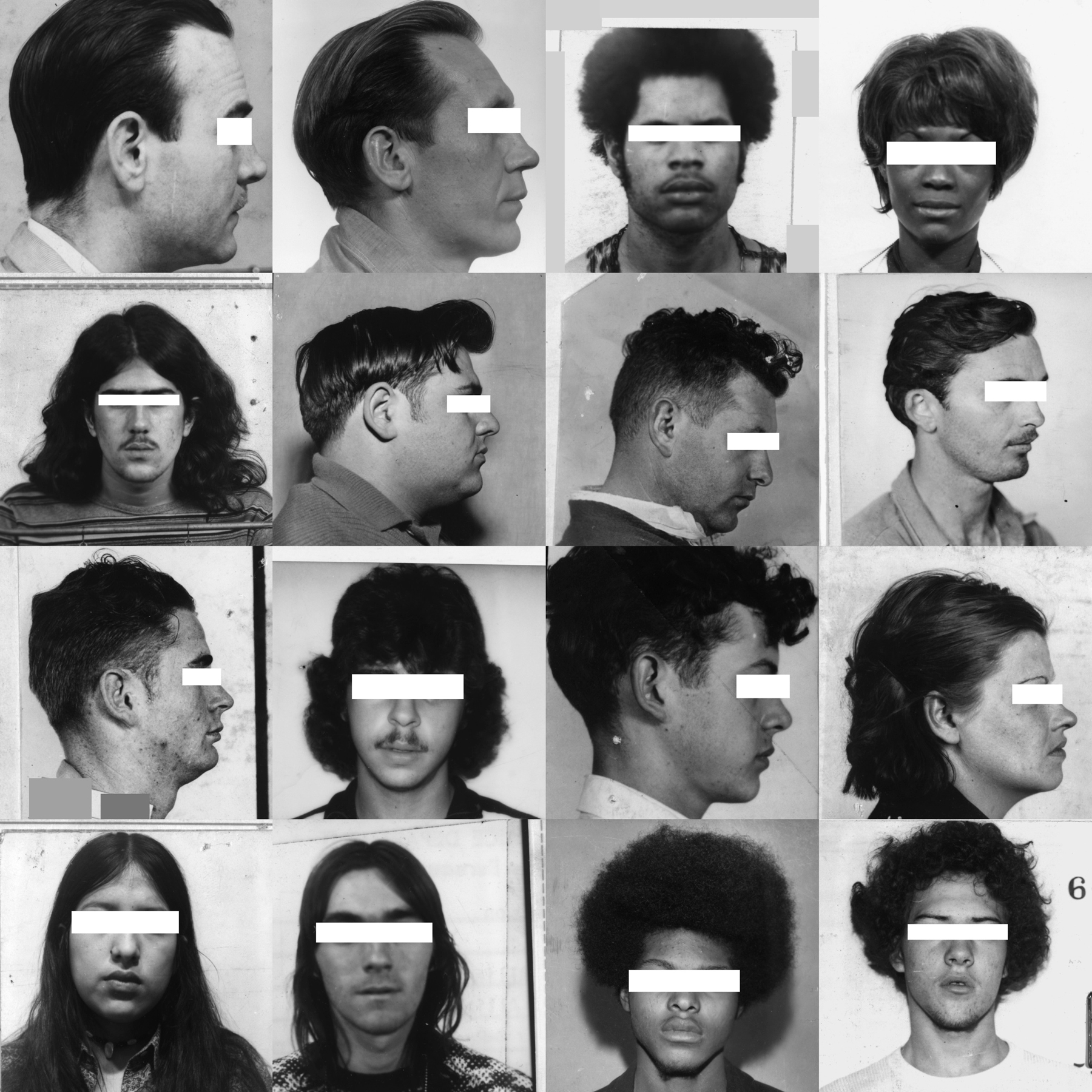

Trevor Paglen, They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead. . .(SD18) (detail), 2019. 3,240 silver gelatin prints and pins; dimensions variable. Courtesy of the artist and Altman Siegel, San Francisco.

Voicelessness is a pervasive consequence of the systemic aggregation of human data characteristics. Trevor Paglen’s They Took the Faces from the Accused and the Dead . . . (SD18) (2019) is a parallel library made of faces sourced anonymously and used to train machine-learning classifiers in biorecognition. Labor to identify these images is done by crowdsourcing, which results in a data set that contains and reflects the accumulated biases of the contributors. The installation is a towering wall of black-and-white photos of mostly Black and white faces in profile or frontal view, with their eyes blanked out. Women of color are less represented than men, and a few anomalies stand out—a woman in a headscarf, a man in a police hat—that seem to introduce cultural accessories in a limited way that might itself reproduce bias.

Paglen’s work makes the case that people, poorly paid and untrained, don’t create clean data sets, being incentivized purely by volume rather than quality of the information processed. Steyerl argues that predictive algorithms don’t reliably approximate human behavior, but rather create expectations based on models that then drive real-world decision making according to abstract rather than concrete realities. Her installation, City of Broken Windows (2018), consists of two monitors on easels, large colored panes of glass propped against the walls, and vinyl text that runs across the walls and the windows of the gallery. One monitor plays a video, Unbroken Windows, documenting the work of Chris Toepfer, an artist/activist in Camden, New Jersey, who creates public art on the windows of disused buildings to discourage neglect and property destruction. Toepfer created the “window paintings” that surround the two videos. The other video, Broken Windows, shows researchers in a former WWII airplane hangar in England who are employed to train AI-powered home-security software to recognize the sounds of glass breaking by repeatedly shattering glass panes with a mallet.25

Hito Steyerl, Broken Windows, 2018. Video still. Single channel, HD video, sound, 6:40 min. Courtesy of the artist; Andrew Kreps Gallery, New York; and Esther Schipper, Berlin.

Steyerl cites two “broken window” theories as the basis for her work. French economist Frédéric Bastiat’s 1850 parable “That Which We See and That Which We Don’t See” explains what he called the “broken window fallacy” that a cycle of disinvestment and rebuilding creates a false perception of sustainable growth where only short-term boom-and-bust cycles exist.26 Steyerl links this idea to contemporary gentrification and the trend of “broken windows policing,” an idea popularized by criminologist George L. Kelling and scientist James Q. Wilson in the early 1980s.27 Adopted by police chiefs, including New York City’s William J. Bratton, in the 1990s, the policy authorized widespread prosecution for minor infractions as a deterrent against more serious forms of crime. Subsequent analysis has revealed that such policies disproportionately subject poor and minority citizens and immigrants to harassment and arrest. The ongoing impact of these directives on communities of color has been well documented.

Lynn Hershman Leeson, Shadow Stalker, 2019. Still from HD video with sound, 10 min. Courtesy of the artist; Bridget Donahue, New York; and Anglim Gilbert Gallery, San Francisco.

While the police of the 1990s relied on a record of minor infractions to determine the potential criminality of a subject, today’s information infrastructure allows authorities and corporations to observe and track all individuals using their associated “data body”28 online in an attempt to anticipate their behavior. Lynn Hershman Leeson’s installation Shadow Stalker (2019) includes a 10-minute film in which Tessa Thompson describes how our personal information is being aggregated, sold, and used to track us without our knowledge. Thompson describes a visual marker on a map—the “red square”—that describes the scope of potential criminal activity in a neighborhood. The “red square” is governed by an algorithm, PredPol, that was developed in 2010 by a coalition of UCLA researchers and the Los Angeles Police Department. The “red square” identifies areas with a high concentration of individuals marked suspicious by their location history, credit scores, email addresses, and other undisclosed factors that are determined abstractly without knowledge of anyone’s life circumstances or personal choices. These markers can have a further negative impact on the social inclusion of those deemed insufficient, as they might find it harder to locate a job or an apartment that would improve their ranking. Thompson ends her monologue with an exhortation to reverse the power of the algorithm by taking control of our data’s circulation and use. She invokes “The Spirit of the Deep Web,” at which point the video transitions to the Spirit, played by January Steward, a futuristic techno-fairy who speaks and sings about Mimi Ọnụọha’s theory of “algorithmic violence,” which is produced by structural inequities that the data body perpetuates.29 Both Thompson and Steward are Black femmes who demonstrate the truth of Katherine McKittrick’s observation that the terrain of political struggle will be traversed by Black women irrespective of whether that terrain is geographic or algorithmic.30

Lawrence Lek’s work in Uncanny Valley explicitly engages racial stereotypes about Asians as drone laborers and subverts them. Drawing on the work of Black futurist artists and theorists who articulate and theorize the ontological space of Afrofuturism, Lek has proposed a corollary: Sinofuturism. Lek maintains that the collectivist, flow-driven character of contemporary futurism maps onto Chinese cosmologies and worldviews in relation to the West. Importantly, Lek does not situate Sinofuturism within China or Chineseness; rather, he asserts that stereotypical views of Chinese people as automata that are popular in the West are aligned with how western society understands technological advancement and automated labor, as well as its relation to the rest of the world. According to Lek, “By embracing seven key stereotypes of Chinese society (Computing, Copying, Gaming, Studying, Addiction, Labour and Gambling), it shows how China’s technological development can be seen as a form of Artificial Intelligence.”31 Lek explains his concept in an hour-long video essay, Sinofuturism (1839–2046 AD) (2016), which was not on exhibit at the de Young but can be viewed on his website. A digital narrator describes how engineers find the responses of AI systems “always surprising,” in a way that emulates the constant “firsts” that racial minorities in the west are always being celebrated for and never seem to surpass.

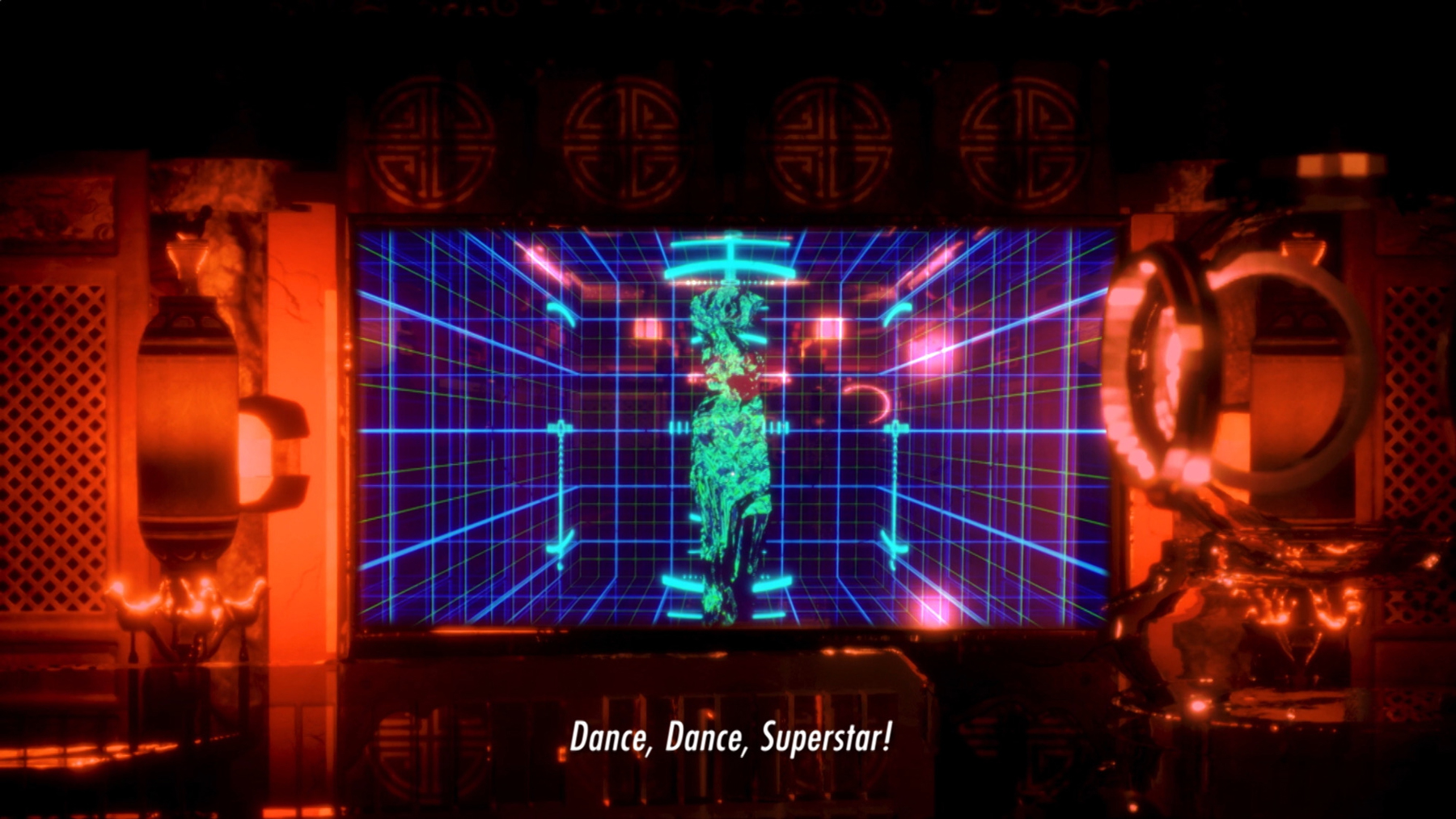

Laurence Lek, AIDOL, 2019. Still from HD video with stereo sound, 82:40 min. Courtesy of the artist and Sadie Coles HQ, London.

Lek’s contribution to Uncanny Valley is a feature-length, CGI animated film, AIDOL (2019), set in 2065. The film tells the story of an aging but revered Diva in a deep philosophical and musical dialogue with an artificial intelligence, Geo. Diva seeks to resurrect her career through a performance in a massive stadium, for which Geo has written the songs. The sponsor of the competition, Farsight Corporation, is an autocratic entity that has supplanted the state as the seat of power. She sings at the center of an eSports battle that rages around her. At one point, Diva suggests to Geo that she is a contemporary bodhisattva, Guan Yin, the intercessor who assists mortals in attaining divine consciousness. The electronic pop songs she performs throughout the film, the juxtaposition of serene natural settings with futuristic ones, and the culminating sequence involving a satellite and a temple manifest the Sinofuturist aesthetic that Lek seeks to articulate in his work. Allegories to the current state of resistance in Hong Kong and elsewhere to the centralized control of Beijing are abundant. Futurism can be a useful tool to talk about the present while circumventing direct censorship.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas and Annika Kuhlmann’s video installation, Being Human (2019), is the only work in Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI that explicitly takes up questions of who is allowed to speak and in what formal language. Kulendran Thomas and Kuhlmann consider the aftermath of the decades-long civil war in Kulendran Thomas’s native Sri Lanka, in which both the national construct and the idea of Tamil Eelam itself was scrubbed from the public record.32 In his work, this erasure interweaves with the more subtle erasure performed by the global contemporary art regime, which allows for difference within specific set parameters that are aligned with the same humanist values that allow a rebel culture to be excised as anomalous to the historical record. In Being Human, Kulendran Thomas and Kuhlmann present deepfake renderings of Taylor Swift and Oscar Murillo spouting personal insights about the nature of success and authenticity. These are mixed in among the words of artist Ilavenil Jayapalan, who describes the difficult realities of the international contemporary artist making work that describes a Global South experience for western venues, and images captured at art fairs and biennials.

Christopher Kulendran Thomas and Annika Kuhlmann, Being Human, 2019. Installation view, Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI, de Young Museum, San Francisco, February 22, 2020-June 27, 2021. Courtesy of the artists and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco. Photo: Randy Dodson.

The work is presented on a two-panel reverse-projection glass that has a couch set in front of it and two small modernist paintings hung on either side. Behind the screen are two abstract metal sculptures and more paintings, which are the work of Kulendran Thomas, Upali Ananda, and Kingsley Gunatillake. These works are in a midcentury modernist style common to artists from art communities that are less connected to contemporary institutions in Europe. The style indicates a break from traditional arts or European-style classicism but can still imply that the artists are not fully in the here and now compared to those who make moving image works or text-based abstractions. Its ubiquity is close to hegemonic in parts of the world where the United States and Europe maintain neocolonial relationships today.

Kulendran Thomas names the problem that permeates the Uncanny Valley exhibition: we cannot articulate posthuman possibilities without first reconstructing the category of “human” to be large enough to cover everyone that ought rightfully to fit within it. From a legal standpoint, if only humans have rights, then any nonhuman entity from the oceans to the dark of night is essentially unprotected from violation by our laws. Indeed, most people are so fully invested in a humanistic logic of rights that the rights of animals are barely taken seriously, nor is their ability to feel pain universally recognized. Rebel populations such as the Tamil Eelam are likely to have experienced a similar lack of protection from violation, since as non-state actors they are not recognized as humans with rights. Echoing Wynter, Kulendran Thomas suggests that Eelam’s history has been eradicated because Tamils are not viewed as fully human, either by the Sinhalese majority in Sri Lanka or by the larger global audience for news. Similarly, contemporary artists from Sri Lanka live on shifting ground, because they are not viewed by the west as a culture with a real popular constituency.

For the de Young to wade into this area of human rights discourse is encouraging, and it closes the exhibition on a progressive note. Still, many of the works reflect wider cultural assumptions that the “human” is a quantifiable entity described by degrees of surveillance and autonomous decision making. Policing is a major undercurrent throughout the exhibition, which Michel Foucault would argue demonstrates that we continue to shape human relations through training in and enforcement of restrictive behavioral norms. Museum-going is a study in these norms, from the “don’t touch” imperative that inhibits many presentations of socially engaged art to expectations that exhibitions not be political in ways that could challenge the established order. While Uncanny Valley: Being Human in the Age of AI includes many works that are alarming or confrontational, few of the works on view truly question the social order that puts wealthy patrons and highly educated elites at the helm of culture.

As with cybernetics, there is a real risk that contemporary art that deals with these issues will fall into a first-order framework that privileges the artist’s individual genius or a second-order framework that foregrounds the artist’s subjective identity position in lieu of hard facts. Either framework perpetuates the privileged position of the artist as a superior cognitive entity to the average human and grants the artwork value on the basis of its productive association with the artist. But artworks are not purely valuable because of the reputations and intentions of their makers; since the late twentieth century, it’s been acknowledged that they have value based on the experience of the viewer. Perhaps this explains why Hanson Robotics’ latest creation, Sophia, is now learning how to paint. If the art is in the mind of the viewer, it shouldn’t matter whether the artist is a human or if they’re even alive. If an AI can get the same benefit that a human artist does from making art— which increases our haptic, emotional, and cognitive capacities—then can the culture get the same benefits from art generated by machines? Visitors to the de Young Museum got a first chance to find out for themselves.

Anuradha Vikram is a writer, curator, and educator based in Los Angeles. She is a member of the editorial board of X-TRA and co-curator of the 2024 Pacific Standard Time Art x Science x LA exhibition Atmosphere of Sound: Sonic Art in Times of Climate Disruption, hosted by UCLA Art|Sci Center.