The protests in Turkey, beginning on May 28, 2013, took place through real and virtual bodies. The realm of the body encompassed more than violence—more than the tear gas, burns from water cannons laced with acidic chemicals, the brutal and arbitrary beatings by police in riot gear, civil police and informal militias, and the final tally of over eight thousand injured, sixty critically, and five dead. It included the idyllic encampment of a park alive with youth, building hope through love and discovering how to shed the skins of divisive labels and loyalties to parties, ethnicities, genders, and even sports teams. Muslims held communal prayers in the park, their space guarded by a human chain of people of every creed. People fell in love. They fell in love romantically,1 but they also fell in love with each other in the sense of people truly seeing each other for the first time. Upon hearing the strength of their own voices enabled to speak honestly and without self-censorship, and of their own ears enabled to listen, people fell in love with themselves. This was not narcissistic compensation for personal failures, but rather a long-neglected appreciation of shared humanity. The protestors suffered immense violence, but they also sustained immense love.

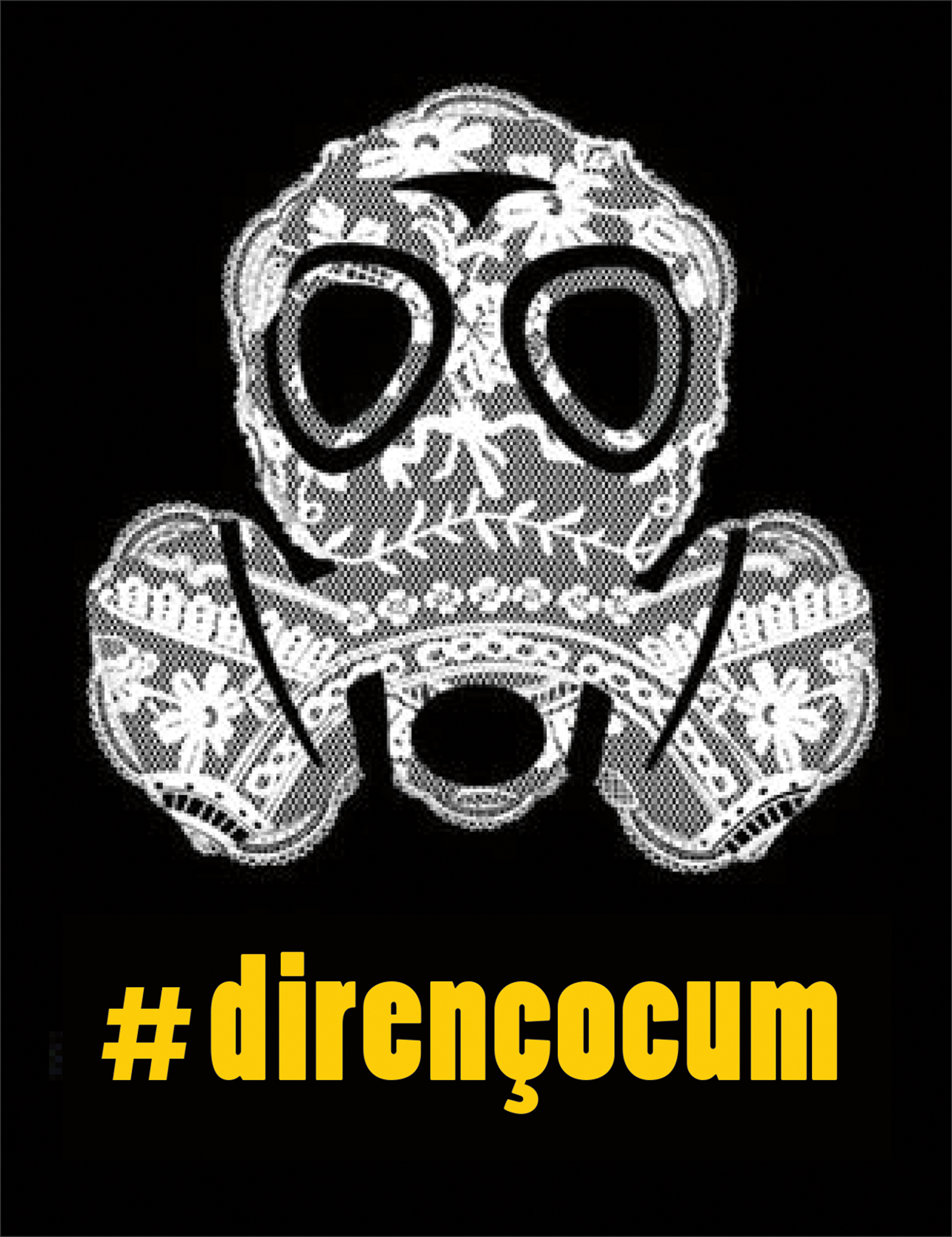

Anonymous, Resist My Child (Diren Çocum), June 2013.

The extent of the violence came as a surprise, even to the people at its heart. Prior to these events, few would have put the ideas of “gas mask” and “Istanbul” together. And no one would have imagined the virulently antagonistic football clubs joining forces, let alone the nationalist, Kurdish, and center-left political parties. For months, those of us living abroad had noticed a sequence of headlines steadily disappearing behind others; a Facebook friend described the dizziness resulting from the rapid succession of unrelated major news events, each new incident veiling its precedents. Turkey has a social memory of hard times: many experienced the military coup of 1980 directly, and everybody experiences its effects today, in the automatic self-censorship and other residual dangers of dissent that persist, including unemployment or incarceration. Nobody imagined that metaphorical smoke screens, built of successive headlines, would imminently become eminently real.

On the evening of May 31, my Facebook feed shifted from its usual eclectic articles and pictures of cute cats to instructions on how to make an improvised gas mask from a water bottle and a handkerchief; maps of police v. protest barricades in the neighborhood where I used to work; recipes for teargas antidotes; announcements about escape routes as well as police traps; reports, photographs, and videos of violence and injuries; and images of tear-gas floating across familiar streets and buildings. The feed came from friends, colleagues, and former students. Social media transfixed expatriates as it disclosed an extended sports match between the forces of good and evil unfurled through the scroll of images and text. One side had Facebook and Twitter. The other had tanks, shields, and weapons. I experienced the sick fascination of a gladiator match: a battle of “pen” and “sword,” technologically ramped up a few centuries.

The nighttime pause in the protests came suddenly, and then began the art. Humorous and passionate, it came as performance, graphic design, cartoons, tweets, and graffiti. It effused love as an antidote to violence. Heartfelt and largely anonymous, it communicated as succinctly as the most effective political art, but in its virtual transience refused commodification. In a virtual platform where creators and audiences merged, it became an art form of protest disengaged from the contemporary art biennials that bracketed it. It was not at the Venice Biennale, where art professionals from Turkey staged marches to draw attention to the initial protests. Subsequently, such popular expression upstaged the Istanbul Biennial, which opened the following September.2 This proliferation of aesthetically conceived political expression underscores the vitality of political art while indicating a disengagement, enabled by the virtual realm, from the institutional frameworks of its physical dissemination. In Turkey, contemporary art has a long legacy of political expression, and numerous artists engaged in the protests and in their discursive aftermath. The shift of public access from the physical to the virtual foregrounds the much-discussed tension between the evocative critique of political aesthetics and the market forces that sustain their production.3

Despite its limited access to established networks of contemporary art production, this proliferation of online political aesthetic expression (in a form dominated by graphic design) engaged a privileged portion of the population. The Turkish university system functions through a centralized examination system based on complex and ever-changing algorithms that claim to match aptitude to profession, but generally match luck and dogged memorization to somewhat randomly selected career paths. A certain score on the exam and the successful navigation of juried evaluations, both rooted in skills of mimetic representation, may enable entry to the state arts academy in Mimar Sinan University; very few other higher educational institutions offer fine arts education in Turkey. Many of these are geared less toward discourses around global contemporary art and more toward local markets and secondary education. Many globally successful contemporary artists and curators from Turkey have sidestepped this system by shrewdly managing their own art educations, with graduate training at private and/or foreign universities and participation in international networks. However, most Turkish students entering the university do not seek the itinerant life of the global arts professional or even have access to the idea of art as a career path; they and their families seek professional stability and security. For students interested in the arts, a career in advertising provides a creative outlet within a corporate world. Since the early 2000s, the explosion of departments of media and communications in private universities in Istanbul has provided a venue for middle- and upper-middle-class urban students to bring the arts and professional viability together.

Increasingly, the activation of social media as a site for political expression also reflects the proletarization of middle-class youth, who find little employment matching their skills (in Turkey, as elsewhere). These are the artists of the Facebook streets: white-collar urban professionals sending up virtual smoke signals. Their new art speaks the language not of art but of advertising. Just as anonymous graphic design in the virtual sphere gave each sharer a role as curator, the adoption of performance art as street protest muddled the distinctions between high art and public culture. In contrast to the cultural capital implicit in the staging of contemporary art, this protest art unearthed an under-utilized realm of aesthetic practice as a mode of political action, producing modes of speech that undermined the role of authorship and indeed the function of copyright on which the art market, and the artists laboring within it, depend.

Protest art responded to the interplay between violence, morality, and pleasure enacted in recent political discourse. On April 30, 2013, performance artist Defne Erdur staged “in between prayers—doing nothing” at the Istanbul Palace of Justice, in which she stood in the courtyard facing the building between the noon and afternoon prayers, until she was expelled from the premises. Erdur posted the event on Facebook:

30 April 2013

between noon—mid afternoon prayer

Istanbul

Palace of Justice C Block

yes, I am here today…

continuing to do nothing

as the decisions,

that I can never internalize

that I

—in the name of being human—can not ignore,

are being taken or not taken here.

and I do not know what else I can do

than coming face to face with my embarrassment,

giving in to the weight of doing nothing,

searching for what it really is “not doing anything.”

I am tete a tete with my lack of knowledge and means…

…in between prayers—doing nothing4

Not only did Erdur’s performance pinpoint the widespread sense of powerlessness within an increasingly repressive society, it also critiqued the incommensurability between the rhetoric of religion used by the ruling Justice and Peace Party (AKP) and its manipulation of law. The work exposed the artist’s body to the state, which rendered it vulnerable through the application of force. As Louis Althusser argued, such resort to physical repression reveals cracks in a hegemonic regime of spontaneous consent, in which subjects, trained through state-sponsored institutions such as the family, school, and religion, accept normative social paradigms as being in their own interest.5

During the month of May, state media attempted to conceal or distract from a series of incidents of violence, using the discourse of public morality to construct an alternate narrative. For example, on May 11, 2013, the town of Reyhanli in the province of Antakya on the border with Syria was devastated by two massive car bombs in the city center that killed 51 and injured 141 people. Minimal attention was paid to these events as the prime minister visited the United States before visiting the site of the bombing. In the immediate wake of these bombings, new restrictions on alcohol caught the public attention, quickly shifting the news cycle away from the tragedy and its murky roots.6 Similarly, on May 26, 2012, Prime Minister Recip Tayyip Erdogan defended his effective abortion ban by announcing that, “Every abortion is an Uludere.” He was referring to the December 2011 slaughter of thirty-four Kurdish citizens of Turkey, mostly minors, from the village of Uludere (Roboski in Kurdish). Affiliated with pro-Turkish militias, the youths were shot down by Turkish military air-craft while participating in a minor smuggling operation across the Iraqi border. The scandal increased when information emerged that the military knew the people they fired on were unarmed, and subsequent family memorials were heavily fined.7What may appear as a lack of public accountability on the part of the administration emerges instead as a media-savvy strategy in which minimal public attention on the part of state leaders combined with media monitored indirectly through corporations produces a carefully constructed, state-supported reality for mass consumption.8

The pattern was not lost on the world of online graphic media. In both cases, border-town tragedies had been overshadowed by intense regulation of the private sphere. Erdogan’s opposition to abortion fit with his frequent exhortations that women should have at least three children, and that contraception, cesarean section, and abortion were practices undermining Turkey’s power.9 Similarly, the alcohol restrictions he claimed as equivalent to consumption laws such as those in Britain or in Sweden suit his comment that anyone who consumes alcohol is an alcoholic, or his implication on May 28, 2013, that the frequently idolized founder of Turkey—Ataturk—was a drunkard.10

A kiss then punctuated the turmoil. In the week of May 20, 2013, a public announcement system in the Ankara Metro warned a kissing couple to behave more modestly. On May 25, police attempted to block metro entry to approximately a hundred couples synchronizing a kissing protest.11 As with Erdur’s work, in choosing to intervene in an otherwise innocuous incident, the police engaged the repressive forces of the state against the freedoms of a private sphere reconceived within the bounds of public morality. In doing so, it marked the limit of “spontaneous consent” for a sizable portion of the public. The predominantly urban and educated groups that have maintained hegemonic power since the foundation of the Republic of Turkey in 1923 perceived themselves increasingly under siege from the rising economic and social power of Islamist groups, represented by the ruling AKP. The street protests that followed can be understood as the tipping point, where these hegemonic groups no longer submitted to the existing order, and where the state, no longer able to maintain order through spontaneous consent, resorted to a repressive state apparatus—using brute force—in order to regain power.

The protests that exploded on May 30 were ostensibly against the construction of a shopping center in Gezi Park, immediately beside Taksim Square, yet it’s clear they reflected far more than a battle between environmentalism and urban planning, or public space and corporatization. Taksim Square, marked by a monument to the nation’s founders on one end and a cultural center devoted to the performing arts on the other, is one of the most symbolic public squares in the country. Taksim Square symbolically replaced the religious public space of the historic mosque courtyard with secular urban public space for a modernized city and its shopping streets and entertainment district in neighboring Beyoglu. Like the long-disputed proposals for a central mosque, the proposed shopping center stood to destroy not simply the park, but also the commercial circulation of the area, as the characteristic private enterprise diffused through small businesses succumbed to corporate investment closely affiliated with the state.

The body emerged as the boundary between the independent individual and the state, as riot police convened around peaceful protesters staging a sit-in at Gezi Park.12 The protesters held books open in front of the police. The protest made literal the common Turkish phrase meydan okumak, in which the words for “square” and “to read” conjure public declamation. Elevating an everyday phrase to a new meaning in order to address a specific contemporary issue, this staged protest functioned identically to Erdur’s performance art, yet it did not require the same cultural capital to engage viewers or to be understood. Rather, photographs of young people reading against a barrier of police shields produced a potent symbol of broader attacks on academic freedom and pointed toward the far broader implications of the protests, which would soon proliferate to incorporate a broad range of conflicts between a large portion of the public and the state.13

Soon, teargas billowed across the square and other parts of the city, a terrifying echo of the Labor Day Massacre at the square in 1976. Unarmed and defenseless, protesters scrambled to the safety of shopkeepers who, acclimatized by earlier, smaller protests, kept antidotes (antacid, milk, and lemons) at hand. Protesters soon equipped themselves with makeshift gas masks (swim goggles and surgical masks) and bottles of antidote. Images of police brutality raced with reports of injuries and death. People initially spoke of dressing in black. Then, refusing to articulate mourning, they chose color instead. As protesters amassed in squares throughout Turkey and the Gezi encampment grew, the production of graphic images and the engagement in performance became as defiant an act of resistance to self-imposed silence as the protests.

The first popular meme emerged from a Reuters photograph dubbed the “woman in red.” The subject was an academic at a nearby university who had been visiting the peaceful protest when she became the target of a blast of pepper-spray.14 As she turns the other cheek, her red dress signaling rather than representing violence, the image displays a precise act of state violence against the individual, without the more disturbing images of lost eyes and bruised limbs that also characterized the protests.

Transforming this unplanned act into a sign through participatory repetition, design students at Dokuz Eylül University in Izmir enlarged the image, cutting out the woman’s face so that protesters could photograph themselves as “the woman in red.” The image was subsequently translated into Legos and then a miniature painting by Taha Alkan, which served as the cover for a special issue of NTV Tarih, a history magazine associated with the Dogan Media Corporation.15Like the “anonymous” Guy Fawkes mask of the Occupy protests, the erasure of individual identity furthered the production of a diverse yet collective voice continuing to emerge both graphically and performatively.

Subsequent photographic memes of female protesters employed far more art historically grounded connotative frameworks, reflecting the sophisticated cultural capital of the participant audience who made them viral through social media. The so-called “woman in black” photograph functioned as an aesthetic trope through the implicit iconography of crucifixion, reflecting the experience of secular yet righteous martyrdom quickly enveloping the protests. The spontaneous decision of Australian student Kate Mullen to stand in front of a police armored vehicle (TOMA) functioned as an unplanned performance with a high degree of photo-consciousness. “I noticed that there was a large group of photographers nearby and in order to emphasize the peacefulness of the protests despite the [police] violence, I decided to stand in front of a TOMA and open my arms. I wasn’t afraid. I didn’t think they would hose me down but if they did, I knew it would be an amazing photograph.”16

Anonymous, Emoticon summary of Protests in Turkey, June 2013.

Such photographs depend on familiar art historical tropes of “revolution,” the scope and objectives of which often remain unclear.17Several photographs emerged from the protests that were recognized for their resemblance to Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People (1834). These photographs rearticulated the myth of a spontaneous popular uprising set against the tenuous hopes of revolution, often articulated through the symbolic deployment of women’s bodies.18 The initial version of this photograph showed a man clambering over a barricade, his hand holding the Turkish flag high as tear gas diffuses under streetlights. In contrast to Zeki Faik Izer’s 1933 rendition of the painting, entitled Revolution Road and familiar through numerous reproductions on history textbooks, here an anonymous everyman emerging like a phoenix from the ashes replaces both leader and masses.19 Stripping down the iconic Liberty to the basic elements of a triangular composition rooted in a barricade and topped by a flag, the image embodies the shock of familiar streets turning to war zones as the despair of loss, indicated by the smoke, competes with the hope of ultimate survival and social change.

The image began to serve multiple ideologies as Photoshop transformed the flag into a rainbow, reflecting the recognition of LGBT rights as part of a broader struggle for civil liberties across all sorts of divisions and going beyond the religious and ethnic politics of earlier generations of political struggle. A second photograph evoking the iconicity of Delacroix’s painting soon overtook the first in Internet popularity through the advocacy of rock star Patti Smith. In that version, a beautiful young woman holds her fingers in a “V for victory” sign, crossing barricades with a group of men behind her, one of whom holds a flag. As with the previous female memes, the figure, in a simple dress with a single shoulder strap, is reminiscent of the personified Liberty. The image underscores the rift between secularists and Islamists. Not only does the iconography of such images mark their reception as belonging to a cultural capital engaged with European values, but also their content speaks to the tacit collusion of the image with the segment of Turkey’s population dominating the protests.

Daniel Etter, Protests in Istanbul, 2013. A demonstrator reacts to teargas fired by Turkish police during a protest in the neighborhood Besiktas in Istanbul, Turkey, June 1, 2013. Courtesy Daniel Etter/Redux.

Repeatedly re-gendered, this feminized trope of Liberty repudiated the masculine rhetoric of the prime minister’s state paternalism.20The anonymity and absence of figures underscores the anti-divisive, anti-hierarchical message of the protests as people from numerous political and ethnic groups came together in order to declare themselves a new “people.” They adopted Erdogan’s characterization of them as “looters” (çapulcu) as a mark of unified identity.21The ability of LGBT politics to supersede the politics of division was perhaps nowhere more clear than in the LGBT Pride Rally in Beyoglu, on June 30, 2013, when the a powerful slogan emerged in the call, “Where are you, my love?” and the crowd’s response, “I am here, my love.” The statement articulated not only the right of interpersonal love regardless of gender, but also the ability of all creeds to participate in the human love marshaled through the protests.22

While many images of covered women in Turkey circulated on social media, ranging from older women with a middle-class head covering who support Republican values to younger, covered Islamist women who disagree with the current regime, this aspect of the social diversity within the protests failed to produce popular memes. While conforming to popular imaginations of Islamism against secular Western democracy, the protests have been rooted in far more complex alliances, signified perhaps most potently by the decision of the muezzin of the Bezmi Alem Valide Sultan Mosque at Dolmabahçe to allow wounded protesters to take shelter at a makeshift clinic during the protests on May 31, 2013. Consequently, the muezzin lost his job and the event became reframed as desecration of sacred space in Islamist media. Thus a moment of cooperation outside of the bounds of polarized politics was rhetorically transformed to restage earlier conflicts between secularists and Islamists in Turkey.23

Anonymous, Graphic of Dervish with Rumi quotation, June 2013.

The relationship between secular and practicing Muslims rejecting state leadership emerged consistently in protest art. In graphic design, such memes included posters of the traditional cracker (kandil simidi) of the holy night of commemoration of the Prophet Muhammed’s ascension to heaven (on June 5). The repeated performance of a Mevlevi-style “whirling” ritual by a man wearing a gas mask and an unraveling shirt used the male body to transgress the boundaries between religious and secular performance.24 Such transformation of Mevlevi ritual into public performance emerged in the 1980s, as the government began to sponsor performances by the Sufi order as part of a program to include moderate Islam within state policy. Although all dervish (mystical) orders in Turkey were banned in 1924, Mevlevi approaches to Islam, rooted in the teachings of the thirteenth-century poet Mevlana Jelalledin Rumi, had long been central to elite urban approaches to Islam and remained part of private religious practice.25In contrast to more radically Islamist Sufi orders, such as the Nakshibendi, and more populist orders with leftist leanings, such as the Bektashi, the recuperation of Mevlevi practice as part of Turkey’s modern Islam in the 1980s enabled rapprochement without alienating Turkey’s secular urban elites. The inclusive message of Rumi’s poetry, embodied in the lines, “Come, come, whoever you are,” gives the secular pluralism of the protests an apparent religious dimension. Transformed into a dance, with emphasis on the performer’s physical prowess rather than on meditative ritual, the performance enables a broad range of receptive address. Religious spectators can view an act of faith in God while atheists can view a more secular expression of culture. This variance from ritual made the Mevlevi performance an effective element of a pro-Erdogan rally in Vienna.26Nonetheless, the immense popularity of the dervish meme in subsequent graphic design clearly reflects a desire on the part of many protesters to depolarize religious issues and enable multiple and liberal expressions of Islamic faith outside of state authorization. As with many of the online tropes, the anonymity of authorship enhanced the ability of online cultural producers and commentators to recycle images that connected previous responses to the evolving chain of events.

Many images self-reflexively articulated the role of social media in the protests. Several designs played on computer software installation graphics, with images of a city being replaced by trees and a slogan such as “installing democracy.” One clever image summarized the protests in emoticons. The penguin meme, emerging in response to a penguin documentary aired by CNN Turk in lieu of live coverage of the violent police repression of protests, came to signify media silence and proliferated in multiple guises.27Soon, a swan meme, representing the less internationally covered but just as brutally repressed protests taking place at Kugulu Park (Swan Park) in Ankara, joined the penguin. The protest aviary grew with the arrival of a Twitter bird wearing a gasmask and a pair of kissing lovebirds as graffiti and graphic-design.28

Burhan Ozbilici, Protesters react as they announce the end of their protests in Kugulu Park, in Ankara, Turkey, Thursday, July 11, 2013. Kugulu Park, or Swan Park, was for weeks a main gathering point for thousands of Turkish anti-government protesters before the return of the swans that were transferred to another place for safety.

Symbolizing the protesters’ refusal to surrender, the gasmask emerged in many guises. The gasmask became a helmet for the Turkcell bunny (mascot of Turkey’s largest cellular phone service corporation, critiqued as supporting the government despite its liberal image); fused with university logos; played on the yarn brand “knitting lady” (Ören Bayan) to become “resist lady” (Diren Bayan); and became a doily in recognition of protesting mothers joining their children in the park in response to Istanbul Governor Huseyin Avni Mutlu’s request for them to take their children home.29

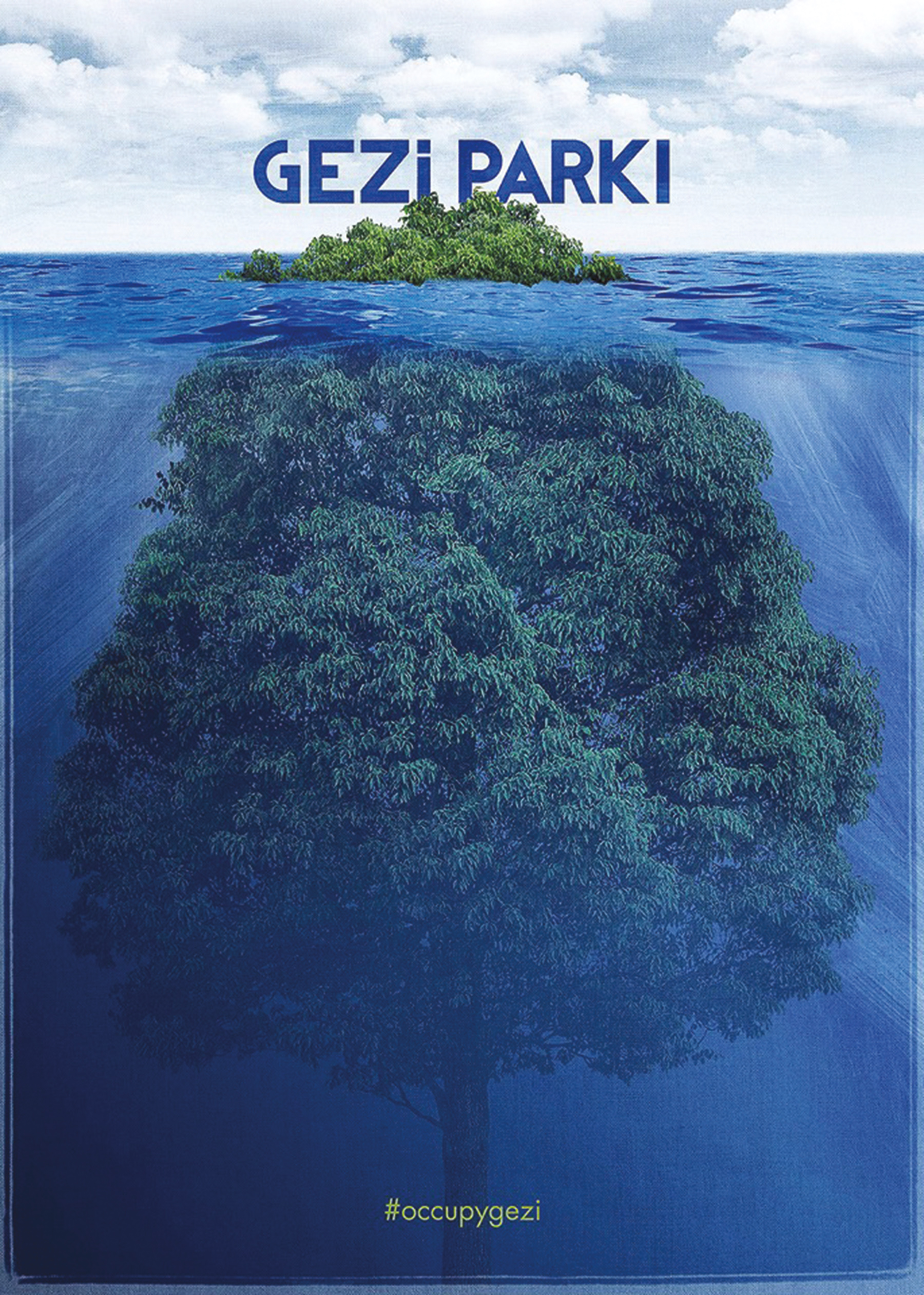

Symbolic of Gezi Park, the image of the tree morphed into a black power fist. Submerged in water, it also served as the proverbial tip of the iceberg or lungs, signifying the park in the first order but also a metaphor between breathing and speaking freely through the mass engagement with the park. A fertile metaphor, the meme of the tree grew to encompass one of the most famous lines from Turkey’s premier Leftist poet of the early Republican Era, Nazim Hikmet, “To live as a tree, alone and free, and like a forest in siblinghood.”30

In this vein, the “standing man” protest became one of the most vital signs of individual dissent. Initially anonymous, a man began an eight-hour vigil in the middle of an eerily empty Taksim Square, facing the Ataturk Cultural Center, on the afternoon after the park had been violently cleared of protesters. Civil police began to nudge him with increasing invasiveness. Recorded by guerilla cameras, they push him, make him take off his backpack and unbuckle his belt, and check his identification papers. The action, echoing that of Erdur and realized by dancer/choreographer Erdem Gündüz, went viral both as a graphic meme and as a performative act of the most basic civil disobedience. Twenty-two people were subsequently arrested for standing.31Standing is a standard gesture of performance art, an art that often requires the elite modes of cultural capital in order to access and understand. In the context of the protests, the act of standing became a personal expression in a context where basic freedoms remain under dire threat. Before long, the gesture of reading as protest from the first day mingled with that of standing, producing a library of opposition enacted on the streets of Turkish cities.32 This development of everyday languages of irony into gestures of protest through aesthetics produces a communicative aesthetic based on popular political expression. These locally developed expressions produce an art of the people—a folk art, as it were—that has nothing to do with the “traditional” forms that have, in the modern era, often served as tropes of homogenized national identity.

Anonymous, Graphic of gasmask merged with the logo for Mimar Sinan University of Fine Arts, 2013. Caption reads, “Everywhere is Taksim.”

In the post-Gezi political environment, the production of politically engaged popular art has dwindled. In its stead, people have continued to search for a means of maintaining a public voice not only through protest, but also through political action. On the one hand, in proliferating grassroots meetings, people have tried to learn how to continue to talk across ingrained differences and to reduce habitualized self-censorship. On the other, they have tried to come together politically, whether through modifying traditional political parties or establishing new ones, such as the Gezi Park Party. Subsequent protest graphics, such as those supporting actions against the building of a third bridge and the destruction of the Middle East Technical University forest for a highway, continue to build on the imagery associated with the Gezi Protests. The continued use of this imagery suggests its function as an avant-garde—not, certainly, an avant-garde of aesthetic progress, but that of social leadership originally indicated in the phrase as coined by the Saint Simonian socialist Olinde Rodrigues in 1825. He proposed that the artist should “serve as [the people’s] avant-garde.” “[T]he power of the arts is in fact most immediate and most rapid; when we wish to spread new ideas among men, we inscribe them on marble or on canvas… [W]hat a magnificent destiny for the arts is that of exercising a positive power over society, a true priestly function, and of marching forcefully in the van of all the intellectual faculties…”33

Anonymous, Photomanipulated image suggesting Gezi Park as the tip of the iceberg in the shape of a tree, 2013.

Through the aesthetic mediation of social media, which enables the proliferation of anonymous tropes reworked and recontextualized by multiple authors, the art of a contemporary political avant-garde eschews the demands of markets and biennials and instead takes up leadership in the voice of the collective. This leader emerges not so much in the artist as in the flexible class of producers/consumers of imagery who have the cultural capital to engage the public without institutional backing. The anonymity of art and performance in the public sphere suggests defiance not only to the powers of censorship, but also to the powers of the market that require an author’s name to serve as a brand. Rather than a politics of origins, through which speech is traced to a single owner verifying authenticity and authority, the politics of such art depends on the authorization of dispersion, in which the repercussion of ideas takes root discursively across its voices, its artists, and its actors.

Wendy M. K. Shaw is a Professor of Global Modern and Islamic Art History and Cultural Studies at the University of Bern, Switzerland. She publishes on the history and historiography of archaeology, art, art history, and museums of the Ottoman Empire and the Republic of Turkey and comparative issues in postcolonial modern aesthetic practice.