In Merlin Carpenter’s DECADES (2014), the graphic Warholesque visages of Kurt Cobain, Amy Winehouse, Debbie Harry, Al Pacino (as Tony Montana in Scarface), Audrey Hepburn, and Michael Caine were emblazoned across monochromatic fields of saturated color. Hung cheek by jowl across the walls of the gallery, these icons of pop cultural rebellion swapped the insipid ambience of a designer-decorated apartment from the 1990s or a hip Hollywood coffee shop on Melrose for the clinical white cube gallery space of Overduin & Co., on nearby Sunset Boulevard. Known for his market reflexivity, conceptual hijinks, and performative painting practice, Carpenter’s laconic array seemed to sit uneasily within a diverse body of work that has sought to displace value from discrete art objects onto conditions of production and reception. Critics, recognizing a genre of DIY sub-Warhols that lurk in “cafes, IKEA showrooms and medical waiting rooms,” found little beyond a cynical rejection of meaning in Carpenter’s subject matter and execution.1 However, the exhibition offered a twist to attentive viewers, who recognized that these seemingly vacant paintings were not silkscreen printed à la Warhol but were, in fact, hand painted by the artist.

Though the paintings in DECADES seemed devoid of meaning, they solicited a perceptual and historical double take: the handmade presentation of a readymade aesthetic evacuated all but a semblance of authenticity from the artist’s touch, while pointing beyond lifestyle appropriations of Pop imagery in recent decades to the ambiguous lineage of the handmade readymade image. Pop art merged hand and machine to stage the dialectic of art and the culture industry in the 1960s, an era in which artisanal painting signaled a vestigial humanism carried over from the preceding decades.2 Carpenter’s contemporary reassertion of hand painting undermined these associations to rid his work of subjective investment. At the same time, his purportedly meaningless subject matter paradoxically reprised a historical dialectic that his practice is otherwise designed to foreclose.

DECADES, installation view, Overduin & Co., Los Angeles June 8–July 12, 20 14. Courtesy of the artist and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

The idea of the handmade readymade emerged during the 1960s, in works that conflated commercial imagery with the trace effects of artisanal production. Evelyne Axell, Gérard Fromanger, Roy Lichtenstein, Sigmar Polke, James Rosenquist, Warhol, and others played the effects of massification—standardization, dematerialization, repetition, and dispersion—against their manual imprints and the attendant promises of originality. Though Pop art was often seen to evacuate aura from the work of art,3 Lichtenstein’s mimicry of Ben-Day dot printing, Warhol’s deliberate inclusion of slippages and manual mistakes in his photo-silkscreen works, and Rosenquist’s appropriation of his own commercial billboard painting technique are only the most well-known examples of a wide-ranging tendency. The term “handmade readymade” was first used to describe these hybrid works by Brian O’Doherty in an opprobrious review of Lichtenstein’s October 1963 exhibition at Castelli gallery, titled “Lichtenstein: Doubtful but Definite Triumph of the Banal.” O’Doherty described Lichtenstein’s art as a jejune extension of Duchampian nominalism in painting, complaining, “His banal work fulfills enough textbook criteria of what art should be that it calls the criteria into question.”4 In a passage that anticipates his 1976 anthology Inside the White Cube, O’Doherty wrote:

When one looks at Mr. Lichtenstein’s paintings as handmade readymades, the problems are much more complex… It becomes art through a process that forces the critic outside art as such to become a sort of social critic. For unless one goes around with one’s eyes closed one cannot help but notice how art of no importance, such as Mr. Lichtenstein’s, is written about, talked about, sold, forced into social history and thus the history of taste, where it is next door to acceptance as art… Mr. Lichtenstein has produced paintings that carry no inherent scale of value, leaving value to be determined on how successfully they can be rationalized, tucked into society and placed in line for the future to assimilate as history, which it shows every sign of doing.5

O’Doherty’s juxtapositions of “art as such” with social criticism, and the handmade with the mass produced, has proven useful for subsequent critics. David Deitcher has argued that Pop art’s “originals that masqueraded as copies” held industrial and artisanal production in suspension at a moment when academic modernism was being promoted as a synthesis of art and design.6 Michael Lobel has suggested that Lichtenstein’s conflation of the handmade and the readymade marked “a struggle between two irreconcilable positions: on the one side sits the idealism of…pure, unmediated vision, couched in the technological language of the sublime. On the other sits the belief in a perceiving subject whose imperfect corporeality denies access to such transcendence, yet may provide an imaginary space of safety set away from the machine’s erasure of subjectivity.”7 The handmade readymade emerges from this discourse as a key to the complex ontology of the Pop image and the interpenetration of the avant-garde and culture industry at midcentury.

Merlin Carpenter, Kurt Cobain, 20 14. Acrylic on canvas, 60 × 60 inches. Courtesy of the artist and Overduin & Co., Los Angeles. Photo: Brian Forrest.

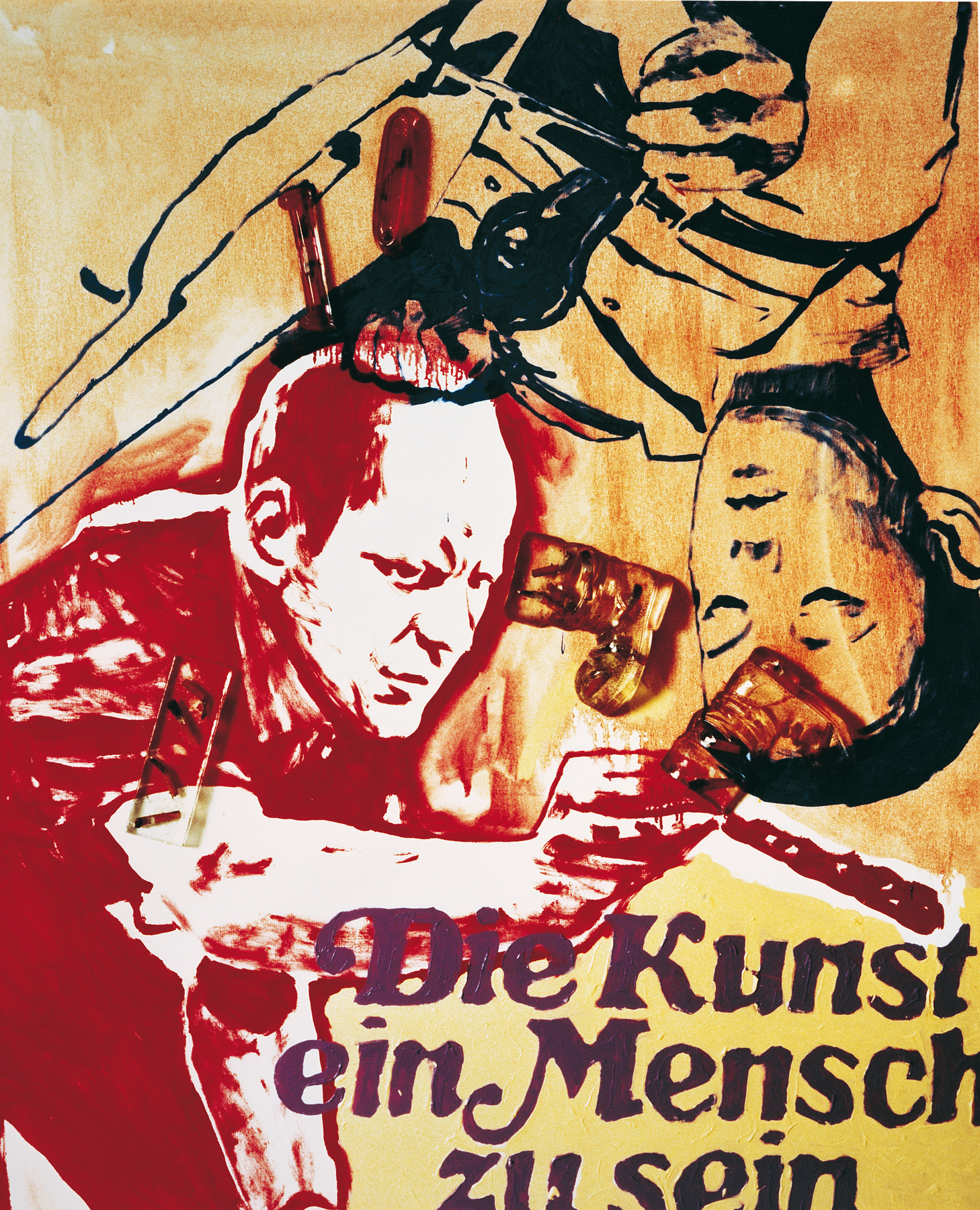

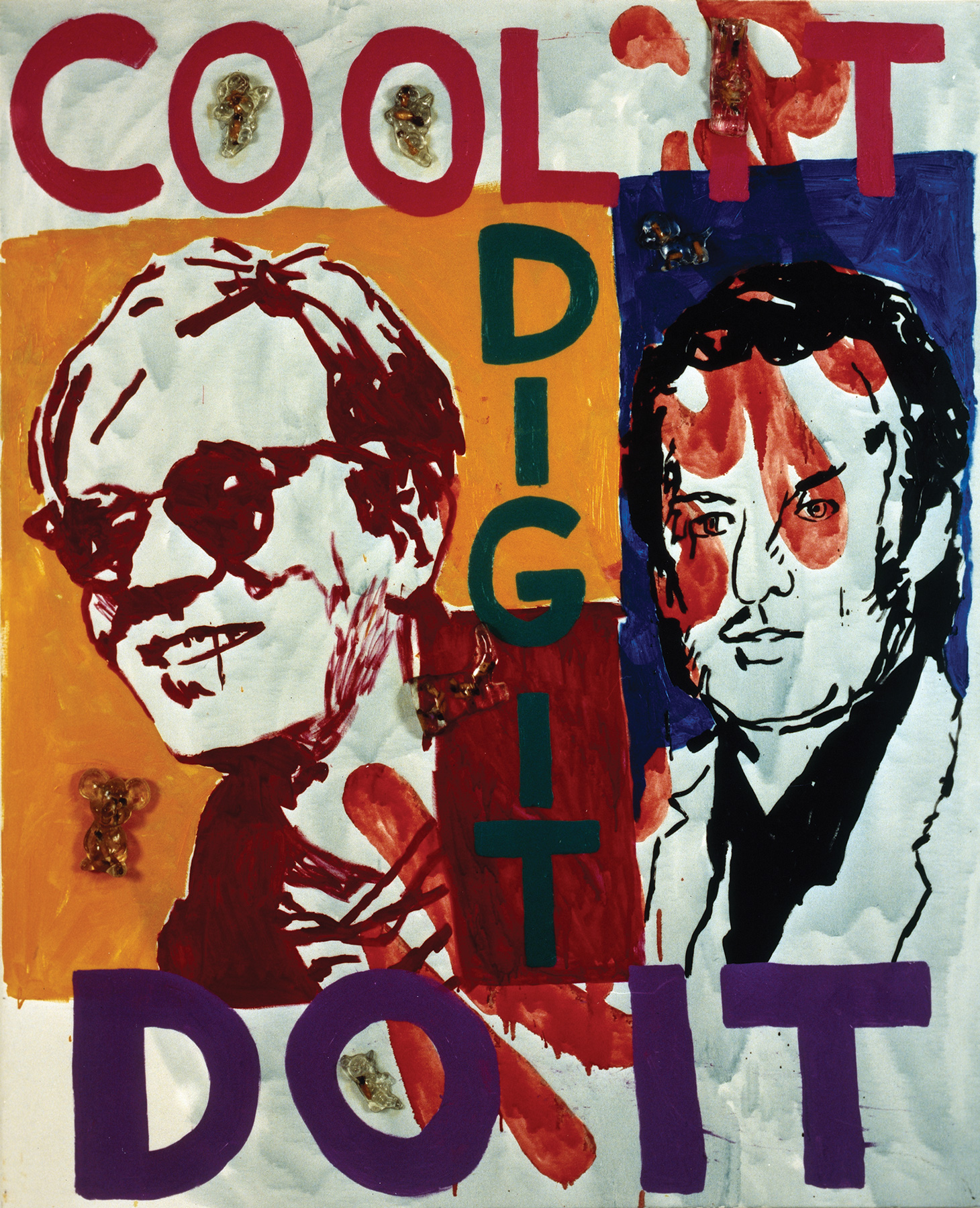

DECADES’s lapidary title could be seen to signal the time lag between this originary moment, when the trace of the hand afforded an imaginary refuge for the creative subject, and Pop art’s subsequent descent into mass cultural cliché. In this negative dialectic of art and the culture industry, the hand collapses from a sign of authenticity to a disabused mark of complicity. This reflexive approach to painting as a means to undermine received notions of authorship stems from Carpenter’s experience working as an assistant to Martin Kippenberger in the storied Cologne art world of the 1980s and 1990s, where artworks functioned as metonyms for outsize personalities and painting was targeted as the fetish object of a hypertrophied market. Kippenberger’s series Heavy Burschi (Heavy Guy) exemplifies the synthesis of creation and destruction, enchantment and debasement that pitted the artist’s celebrity persona against painterly effects. For a 1991 exhibition at the Kölnischer Kunstverein, Kippenberger had an assistant (Carpenter) make paintings from catalog reproductions of his work featuring commercial lettering and flattened Pop images of celebrity artists. Kippenberger deemed the results “too good” to exhibit, so he had them photographed and destroyed. The remains were piled in a plywood dumpster in the center of the gallery, and the photographs were hung as substitutes. In a work inscribed with the words “Die Kunst ein Mensch zu sein” (Art Makes You a Man), Hans Namuth’s photograph of Jackson Pollock flinging paint is set against an inverted depiction of Kippenberger painting as a boy, summoning oedipal themes of predestination and self-destruction. Another work juxtaposed the visages of Warhol and Kippenberger with the text “Cool it, dig it, do it.” In these works, which were made with an opaque projector to flatten the source images, photography was the departure and end point, and the authenticity of painting was undermined. Heavy Burschi put the apparatus of Kippenberger’s practice on display as painting, photography, and the artist’s assistant were summoned and negated in a performed involution of artistic transmission.

Martin Kippenberger, Untitled (from the Heavy Burschi /Heavy Guy series), 1989/90. Color photograph, 47 × 39 inches. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne.

Martin Kippenberger, Untitled (from the Heavy Burschi/Heavy Guy series), 1989/90. Color photograph, 70 × 59 inches. © Estate of Martin Kippenberger, Galerie Gisela Capitain, Cologne.

“I couldn’t give Kippenberger my ideas fast enough,” Carpenter has written, “I needed his assistance to dispose of them.”8 For his first exhibition at Reena Spaulings Fine Art, in New York, A Roaring RAMPAGE of Revenge (2005), Carpenter returned Kippenberger’s gesture and broadened it to appropriate his gallerists and ultimately his audience as assistants. Excerpting The Bride’s (Uma Thurman) monologue in Kill Bill: Volume 2 (2004) for his title, Carpenter instructed his dealers to make a series of quick gestural paintings reproducing media images of the 9/11 attacks on the World Trade Center, depicting their explosion and collapse “in the style of Josh Smith” (who was at the time a “hot” artist showing at the gallery).9 Over these Carpenter printed reproductions of one year’s worth of Reena Spaulings press clippings, charting the gallery’s rise in Chinatown against the reality and aftermath of the 9/11 attacks. The paintings were stacked against the wall for viewers to rifle through like records in a crate, and the flier for the exhibition reproduced the famous photograph of Warhol shopping for groceries at Gristedes. This menacing allegory of revenge and victimization conflated the pathos of art world relationships—between dealer and artist, artist and assistant—with media representations of the 9/11 attacks. It was built on an allusion to the first work that Kippenberger exhibited as an artist, Uno di voi, un tedesco in Firenze (One of You, a German in Florence, (1976–77)—a vertical stack of canvases measuring nearly the artist’s height that were painted with black-and-white motifs from newspaper clippings and from his own photographs. Kippenberger’s absurdist gesture tied the material contingency of painting to his own physical proportions, reinscribing him as author and replacing “parameters that are immanent in the material with parameters that are completely external to it.”10 RAMPAGE thus reprised an originary work of Kippenberger’s and used Reena Spaulings (a gallery and artistic pseudo-collective that produces artworks under the same name) as assistants, while anchoring these value displacements in the question of the handmade.11 If the artist Reena Spaulings leeches symbolic capital from the stable of artists she exhibits as a gallerist, and artists exploit their assistants, RAMPAGE turned the tables by figuring a void at the center of authorship where Carpenter was expected to produce.

Merlin Carpenter, A Roaring RAMPAGE of Revenge, 2005. Installation view, Reena Spaulings, New York, November 2–December 1 8, 2005. Courtesy of the artist and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Farzad Owrang.

For the philosopher Giorgio Agamben, the assistant is a displaced, dispossessed, and incomplete being that nonetheless signals the unrepresentable chasm of “oblivion and ruin, the ontological waste that we carry in ourselves.”

[Assistants] embody the type of eternal student or swindler who ages badly and who must be left behind in the end, even if it is against our wishes. And yet something about them, an inconclusive gesture, an unforeseen grace, a certain mathematical boldness in judgment and taste, a certain air of nimbleness in their limbs or words—all these features indicate that they belong to a complementary world and allude to a lost citizenship or an inviolable elsewhere… The assistant is the figure of what is lost. Or, rather, of our relationship to what is lost. This relationship concerns everything that, in both collective and individual life, comes to be forgotten at every moment… [H]e spells out the text of the unforgettable and translates it into the language of deaf-mutes.12

Agamben’s tragicomic meditation on the ontological displacement of characters in Franz Kafka, children’s literature, and Sufi mystic Ibn al’Arabi’s The Meccan Revelations resonates with Carpenter’s use of assistants to surrogate subjective investment, as well as his conscription of others into this bowdlerized state. Carpenter’s two-year long project The Opening drafted not his gallerists but his audience as assistants; or rather Carpenter assisted his audience in their production of his work. In these “painting actions,” as Isabelle Graw has termed them, the handmade figured the void left by the artist’s displacements.13 Beginning in September 2007, Carpenter staged a series of performances in which the paintings were made at the opening. At Reena Spaulings, the audience stood around with thirteen blank canvases hanging on the wall; piano music, vodka, cucumber sandwiches, and flowers provided atmosphere. At a certain point, Carpenter walked up with a bucket of black paint and scrawled phrases such as “Die Collector Scum,” “I Like Chris Wool,” and “Relax it’s only a Crap Reena Spaulings Show” across six of the canvases, with some of his marks continuing onto the gallery wall. Performed in different variations over two years at Overduin & Co. (Los Angeles, 2008), Galerie Christian Nagel (Berlin, 2008), Galerie Mitterrand + Sanz (Zurich, 2008), Simon Lee Gallery (London, 2009), and dépendance (Brussels, 2009), these painting actions summoned the avant-garde legacy of Allan Kaprow, Yves Klein, Georges Mathieu, Niki de Saint-Phalle, Robert Rauschenberg and others, only to stage their absorption as “value added” for the art market. The Opening not only expropriated the symbolic capital of art history and of the audience in attendance but also, as Caroline Busta has noted, limited production to the opening itself, so that Carpenter would be “making art only during the exhibition’s opening, when he would be ‘working’ anyway.”14 If The Opening provided a kind of social reciprocal readymade, Carpenter nonetheless anchored authorship qua complicity in the scrawled and splattered paint on white canvas.

The Opening, installation view, Reena Spaulings, New York, September 23–October 28, 2007. Courtesy of the artist and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Farzad Owrang.

A final example brings Carpenter’s vitiation and reconstitution of hand painting into focus. The paintings in Hands Against Hands (Reena Spaulings, 2015) use as their starting point his friend Josephine Pryde’s photographs of hands holding various touch-sensitive IPS screen devices. Carpenter mimicked Pryde’s photographs and interposed his own gestural responses in overlapping layers, leaving the source image twice removed. Pryde’s photographic meditation on a technological matrix of vision and touch was reprised through gesture, thematizing the tension between manual and mechanical imagery. Carpenter also sardonically painted the walls and floor silver, irreversibly substituting the shabby chic ambience of the gallery’s chipped rusticated wall paint for an embarrassing throwback reference to the glory days Warhol’s Silver Factory and of New York underground culture. The paintings in Hands Against Hands bore titles mined from Marx’s Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, such as “Man as a mere workman who may therefore daily fall from his filled void into the absolute void—into his social, and therefore actual, non-existence.” The $40,000 price of each painting was listed on the press release in an acerbic jab at critique as value-added collector bait. These involuted gestures implicated Carpenter’s social relationships, the downtown status of Reena Spaulings, historical materialism, and the fetish for the handmade in a matrix of symbolic and market value.

Hands Against Hands, installation view, Reena Spaulings, New York, November 8–December 6, 201 5. Courtesy of the artist and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Joerg Lohse.

Hands Against Hands, installation view, Reena Spaulings, New York, November 8–December 6, 20 15. Courtesy of the artist and Reena Spaulings Fine Art, New York/Los Angeles. Photo: Joerg Lohse.

Warhol famously claimed, “Pop art took the inside and put it outside, took the outside and put it inside.”15 While celebrating the incorporation of the creative subject by the image-driven symbolic economy of the 1960s, the statement captures the pathos that attended Warhol’s “deeply superficial” transgression of the limits of inside and outside and the tragic collision of the culture industry with formerly recalcitrant realms of subjectivity. In his recent text “The Outside Can’t Go Outside” (2015), Carpenter goes a step further than Warhol in dispensing with notions of art’s resistance to exchange. Examining theories of art and surplus value proffered in the wake of the 2008 financial crisis, Carpenter argues that critical practices, far from pointing to an “outside” of exchange, instead supply managerial information or “control value” that streamlines profits for capital:

[Control value] could create role models for subservience to capital, or mentor industries around which productive or non-productive wage labour can happen at the margins by pushing creative technology toward the market. Or it could be about dropping casual tips for speculative investments to keep capital ticking over as it awaits further productive use. Criminals, police, lawyers, artists, academics, bohemians and so on, may prepare the ground for the exploitation of human labour by unwitting research into more specialised, socialised and efficient public or private circulation, enabling rapid turnover and reducing deductions from surplus value.16

In this densely argued text, Carpenter suggests that by perpetuating a fantasy or “trance” vision of an outside of value, art provides a targeting mechanism for capital in its quest for profit, staging an inevitable crash of trance into instrumental value. Veering toward Debordian resignation, Carpenter argues, “The problem with an exceptional artist like John Knight is that because he is an exception, the last bastion of institutional critique, this is a guidance system for the market. It is not that the critical message of institutional critique is any kind of problem, in fact the content that it has is irrelevant—it is that this element, whether critique or not, marks itself as an outside.”17 While some might dismiss this line of thinking as a kind of knowing cynicism, it reflects a growing desire, since the crisis of 2008, to directly confront uncomfortable realities surrounding the market value of critical/political practices. Andrea Fraser’s 2011 article “L’1%, C’est Moi,” for example, launched a powerful call for artists and critics to evaluate “political or critical claims on the level of their social and economic conditions” and to “insist that what artworks are economically centrally determines what they mean socially and also artistically.”18

Warhol has long served as a horizon for those grappling with the fact that avant-garde practices, though notionally antagonistic to capitalism’s depredations, have nonetheless acted, according to Thomas Crow, as “a kind of research and development arm of the culture industry” whose innovations are ultimately “as productive for affirmative culture as they are for the articulation of critical consciousness.”19 For Benjamin Buchloh, Warhol is “but the most conspicuous of postwar artists situated in the moment when culture industry and spectacle massively invade the once relatively autonomous spaces, institutions, and practices of avant-garde culture and begin to control them.”20 Carpenter’s response to this well-rehearsed Adornian problematic and to the hypocrisies that Fraser detailed parallels that of other artists, such as Bernadette Corporation, Claire Fontaine, and Ed Lehan, in that it seeks to evade control value by presenting already-recuperated content. Warhol knockoffs, the work of friends and assistants, and the audience itself are proffered as a means of “feed[ing] the art world to the art world.”21 As a result, DECADES leaves nothing but the trace of the artist’s hand to sustain the valorizing apparatus of contemporary art. While Pop art’s handmade readymade suggested the residual possibility of humanistic transcendence, the handmade in DECADES and other works acts more like a fingerprint at a crime scene—a mark of complicity foreclosing any notional outside.

Swapping trance for crash and transcendence for complicity, DECADES would seem to achieve a Pyrrhic victory against value—whether expressed as market price or critical interest. Yet by staging the collapse of Warhol’s silkscreen aesthetic into mass cultural cliché, Carpenter retroactively revokes the symbolic value (or critical interest) of Pop art, and it is here that a paradoxical historicity emerges:

To prevent this “outside” from becoming just a decorative capitalist fantasy like a video game—and thus an assignable space—one has to refuse its status as reality rather than reinforcing it. This is not the trance of surrealism, or of psychoanalysis, where what is imaginary is considered equally real, but one simultaneously more full and empty. It is totally non-existent, and yet because it negatively relates in a structural way to capitalist existence is also more important than these older definitions, and in that sense perhaps even more substantial.22

If the outside exists to the extent that it creates real “substantial” effects, meaning persists in Carpenter’s practice as a performed failure to foreclose a historical dialectic of art and the culture industry. The tragedy of the handmade readymade is recast in Carpenter’s farce, and the critic is once again forced outside the boundaries of art as such.

Liam Considine is an art historian and critic based in New York. His writing on postwar and contemporary art has appeared in publications such as Art History, Art Journal, The Brooklyn Rail, and Tate Papers.