If you know anything about Trent Harris at all, you probably know his trio of films, The Beaver Trilogy, an epic documentary begun in 1979 that only emerged in its current form in 2001. The Trilogy garnered acclaim from Artforum and National Public Radio’s This American Life because of its strikingly reverberant form and its subtly queer politics. The original film follows Richard LaVon Griffiths (stage name “Groovin’ Gary”), an aspiring actor from Beaver, Utah, who happened to grab Harris’s attention in the parking lot of KUTV Channel 2 in Salt Lake City, where Harris worked from 1978 to 1981. Harris had just graduated from the MFA film program at University of Utah and was working on an innovative local television program that paired young filmmakers with journalists to produce short form documentaries for a program called Extra. The local owner of the station had been convinced by his filmmaker daughter to embark on this experimental endeavor and he gave Harris a significant amount of creative freedom and financial backing.

You can see the results of this high-resource, low-stakes environment in the recent retrospective Trent Harris: Echo Cave at the Utah Museum of Contemporary Art (UMOCA) in Salt Lake City. In addition to screening his hard-to-find feature films, viewers can watch early archival footage of Extra in a furnished, shag-carpeted living room recreated by the museum. In one episode, Harris charts a day in the life of the local dogcatcher. In another, an exposé of price gouging by gas companies plays over footage of a spaghetti-eating contest. One can’t help but be struck by what constitutes “news” in Salt Lake in the 1970s, and by the show’s devotion to local subject matter.

When Griffiths concocted a local talent contest to showcase his own exquisite “pantomime” of Olivia Newton John’s Please Don’t Keep Me Waiting, Harris took him up on his invitation to film the event. The term “drag” is never used in the film and it’s clear that Griffiths worked hard to separate his impersonation from his own gender identity. “If it’s on television, people will understand,” Griffiths repeats nervously in the moments leading up to his performance. Harris’s original documentary captured not only the power and pathos of a small town eccentric, but also Griffiths’s belief in television’s capacity to transform marginality into cultural capital. The footage never aired; Griffiths became distraught and shot himself, but survived.

Trent Harris, still from The Beaver Trilogy, 2001. Part 3: 16-mm film, color, 85 minutes. Courtesy of the artist. © Trent Harris.

While earning his second MFA in directing at the American Film Institute in Los Angeles from 1983 to 1985, Harris dramatized Griffiths’s story, casting another aspiring actor, Sean Penn, in the role of the Beaver Kid. A third version stars a young Crispin Glover in the role of the Orkly Kid. Edited together in 2001, each newly elaborated attempt to nail down Griffiths’s story became part of a monument to time, trauma, memory, and regret. These themes reappear in Harris’s recent works, such as Luna Mesa (2011), and in the structure of his UMOCA retrospective. All three films in the trilogy rely on collage techniques to unhinge mimesis from any sense of a true referent. The Beaver Trilogy is about elaborate forms of self-representation, but it is also about the ways that manufactured images can represent the world back to the self. In the second installment of The Beaver Trilogy, for instance, a sleazy director character appears as a clear proxy for Harris, and Griffiths is stopped from shooting himself by a phone call from a friend. In the third version, Griffiths saves himself in a moment of valiant self-acceptance.

The Beaver Trilogy looks a lot like contemporary video art, for example Pierre Huyghe’s Third Memory (1999), and it similarly addresses the belated temporality of memory, in particular traumatic memory. Like Huyghe’s Third Memory, a two-channel video installation that reenacts the 1972 bank robbery upon which the film Dog Day Afternoon (1975) was based, Harris’s trilogy uses the memorial intimacy of spaces filled with projected light and employs collaged video as a vehicle for (often unreliable) acts of testimony and witness. Whereas Huyghe relied on the memory of bank robber John Wojtowicz as a test case for such mediated memory, The Beaver Trilogy comprised a personal effort by Harris to “work through” Griffiths’s suicide attempt and his role in it.1

The pensive, elegiac form of The Beaver Trilogy departed from that of Harris’s two feature-length narrative films. Plan 10 from Outer Space (1994), is a fictionalized account of Mormon theology that combines the charm of a Doris Day musical with the visionary sets of the 1924 Soviet silent space travel film, Aelita: Queen of Mars. Rubin & Ed (1991) is a zany buddy comedy about two Republicans who set out to bury a dead cat in the desert. Filmed in the otherworldly landscape of Goblin Valley State Park in southern Utah, Rubin & Ed was Harris’s only film to receive distribution, but had the misfortune of premiering in the midst of the Los Angeles riots.2

Trent Harris, still from Plan 10 from Outer Space, 1995. 16-mm film, color, 80 minutes. Courtesy of the artist. © Trent Harris.

With its elaborate set design by Utah artist David Brothers and its thoroughly Mormon plot line, in which Mormon Doctrine turns out to be the key to unlocking an alien conspiracy to take over the planet, Plan 10 signaled Harris’s full return to the surreal purity of his home state, after having spent 13 years in Los Angeles. I had the opportunity to interview Harris in late April as the show at UMOCA was closing, and I asked him to reflect on the local environs. “One of the reasons Salt Lake [City] was founded is that it’s so isolated. When you think about it, there isn’t another city for 700 miles. That’s why Brigham Young chose it. It was isolated and he wanted to start his own country. Only in the last few years has that isolation started to break down.”3That remoteness has allowed Salt Lake to emerge as a kind of simulacrum of the holy land, a fully planned, highly ordered desert capital. “You can find places here where you can see 50– 60–70 miles… It’s kind of like the surface of a mirror when you start walking out on it. You can walk forever and you seem to be in the same place.” A pervasive whiteness shimmers in Harris’s films as an uncanny mirage of American wholesomeness, from the false snow of the salt flats to each town’s gleaming temple and the toothy smiles of Salt Lake’s inhabitants. Responding to this extreme visual and moral clarity, Harris’s stories often evince a sense of the conspiratorial surreal familiar from the work of David Lynch or Thomas Pynchon. It’s as if underneath the zany, the perverse, and the non sequitur lies a knowable, coherent logic sourced not from dreams but from stark reality.

Like universities on the East Coast, the University of Utah benefitted from defense contracts secured in the 1960s and was, similarly, an incubator for technological art forms. The electronic composer Vladimir Ussachevsky was composer-in-residence starting in 1970, and the film department began offering digital animation courses shortly thereafter. Harris remembers early attempts to produce digital images of spheres and cylinders in his classes; even more he remembers this incredible access to technology contrasted against the remoteness of the landscape. “I saw an Ingmar Bergman movie, The Seventh Seal (1957), and went to the film department, which consisted of one guy. He handed me a super 8 [camera] and told me to go make a film. I had to ask him how to turn it on and where the film was. I went out to the Salt Flats and made a film called Mud. Sometimes there’ll be a thin layer of water that covers Bonneville for miles and then there’s this kind of scum that floats on it. It’s quite extraordinary to look at. I put it to a Jimi Hendrix soundtrack. I’ve worked on a project every day since.” It seems appropriate that Harris would locate his own origins as a filmmaker in Bergman’s end-times fantasy; The Seventh Seal’s existential consideration of death through the codes of medieval Christian chivalry mirrors Harris’s own recurrent themes of religion, memory, and death.

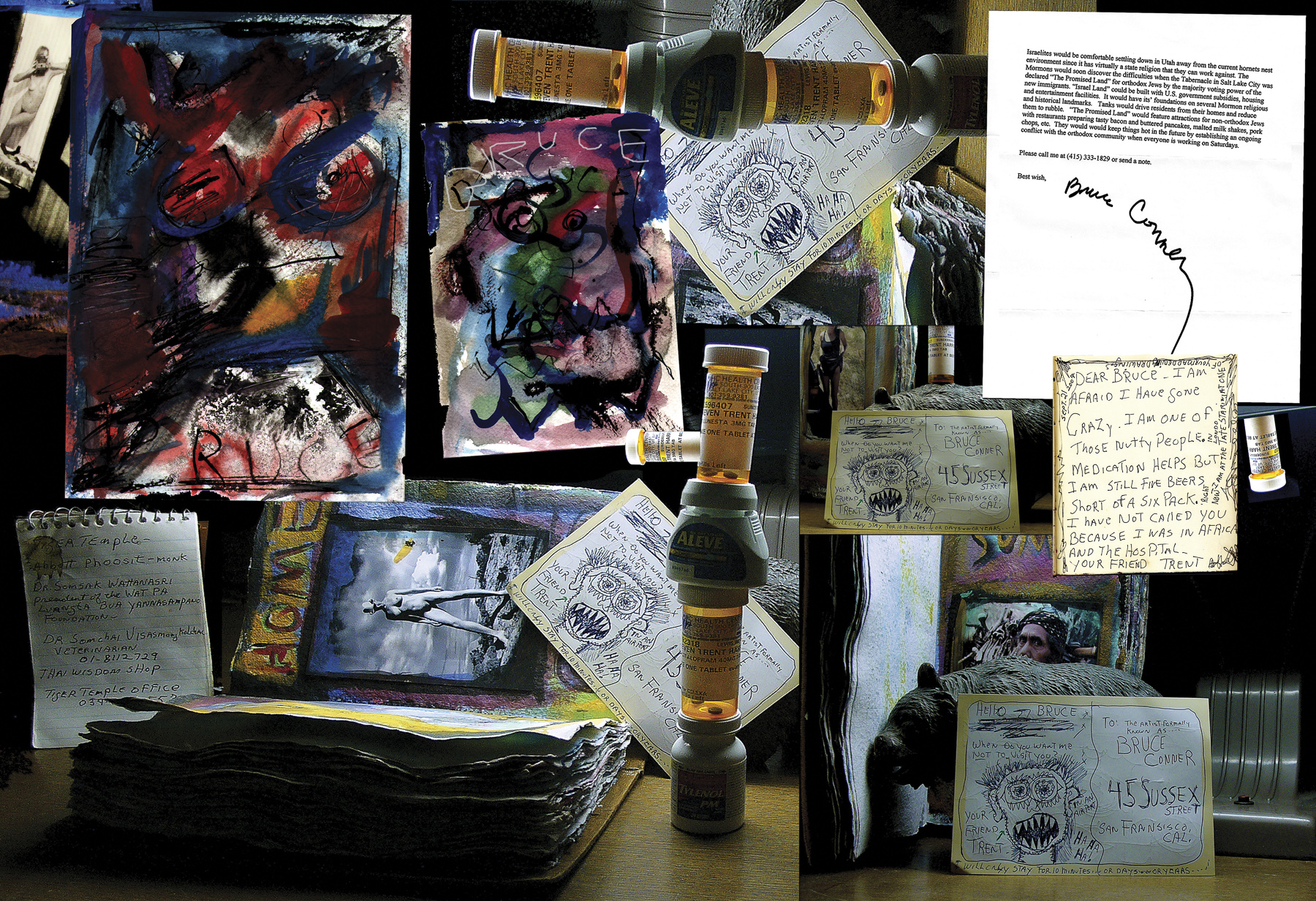

Trent Harris, Bruce and Me, 2013. Photo collage, 17 × 24 inches. Courtesy of the artist. © Trent Harris.

Even the landscapes that populate Harris’s films recall Bergman’s desolate beach. Stark and remote, the Utah landscape demands acknowledgement of its repressed technological and psychological burdens. Projects like the Center for Land Use Interpretation, which maintains a residency in Wendover, or even Smithson’s Spiral Jetty just north of Salt Lake, also address the simultaneously utopian and post-apocalyptic quality of the setting. While his films highlight the unexpected decay underneath the region’s pristine surfaces, Harris makes use of the comedic and heroic potential in its aspirational normativity. For instance, Harris’s first photograph, taken at age 11, which opens the UMOCA retrospective, shows his older relatives in their Sunday best posed curiously below a large plastic octopus. The caption reads, “At that moment I developed a benevolent respect for the bizarre.”

Despite being the first museum retrospective of Harris’s work, the exhibition feels less like a summation of Harris’s career than a continuation of the working through process that began with The Beaver Trilogy. The show is an effort by the artist to chart, quite literally, the recent currents of his work. Large arrows, sometimes elaborated with short captions, lead the viewer through early photos, fantastical props from his feature films, a digital collage of still images taken on his more recent documentary trips, hand-made books, and selections from his correspondence with the late Bruce Conner (titled Bruce and Me, 2013). The progression through these objects is not entirely linear. It’s more like a free associative flow chart, the grand finale of which is the Echo Cave of the show’s title, a video collage that rends Harris’s films into a cacophony of fragmentary images and sounds. In a single channel video, a tiled array of these very short clips plays simultaneously, with each clip disappearing and reappearing in a new location on screen. The installation mimicks those old memory card games that were supposed to teach us visio-spatial concentration, but felt instead like induced dementia.

The trope of the Echo Cave is borrowed from a transformative moment in Rubin & Ed, when an ancient drawing by mythical “echo-people” triggers a vision for the main character, in which the traumatic memory of his cat’s murder returns as an elaborate scene of wish fulfillment gone sour. Later, the echo-people reappear in the guise of an incantatory self-help seminar, which Rubin up to this point has avoided joining. In a moment of self-recognition, he declares himself the group’s king.

Trent Harris, still from Luna Mesa, 2011. HDV, color, 60 minutes. Courtesy of the artist. © Trent Harris.

Fantasy, reality, and memory intermingle in Harris’s Echo Cave, a place where the past is reckoned and future directions emerge. Within Harris’s cave, as in Plato’s, sounds and images reflect back as secret messages that are in need of interpretation but have the power to unveil the subject’s true origin. In his structuralist analysis of Balzac’s story “Sarrasine” (1830), Roland Barthes reduced every stay or stop in a narrative to the passage of a hero through a landscape. Each swamp, forest, and cave that delayed that forward progress was coded feminine.4 Luce Irigaray famously interpreted Plato’s cave as a kind of womb, an “hystera,” from which Plato hoped his prisoners might ultimately escape by turning away from the copies toward original form and the light of day. Irigaray, on the other hand, reoriented our view away from the sun and toward the maternal origin of the cave itself.5

In Harris’s films, the cave, as the metaphorically laden site of this recombinant shuffle of memory and mimesis, drives the plot forward by thickening the forest of signs, making all possible forward movement meaningful. However, the cave is also disorienting, since no direction is more meaningful than any other. “[Y]ou will always already have lost your bearings as soon as you set foot in the cave; it will turn your head, set you walking on your hands…”6 Similarly, Harris’s female protagonists participate in the cave’s “projection, reflection, inversion, and retroversion.”7 Nehor, Karen Black’s character in Plan 10, shares her name with a male villain from the Book of Mormon, who preaches universal salvation and rejects the necessity of repentance. Harris hands over the male gaze to this beautiful chanteuse, who surveys Earth’s inhabitants from above, while plotting a feminist takeover. When asked about the role of Nehor, Harris simply stated, “In my life women have always been the most powerful people in the family…The men were a mess. The women held everything together.”

In the decade between Plan 10 and The Beaver Trilogy, Harris produced one feature, the political satire Delightful Water Universe (2008). He has spent the majority of his time making short documentaries and working on the PBS series Religion and Ethics for WNET in New York. The regional fascination of his early work for Extra is in evidence throughout his work. Harris continues to make “Mondo” films about roadside attractions of rural Utah, but he has also travelled to places such as Burma, Sierra Leone, and Cambodia to document religious and political conflicts.8 In particular, his film Diamonds, Cannibals, and Children with Guns (2004), which documents the activities of the Revolutionary United Front and the plight of child soldiers in Sierra Leone, is jarring in contrast with the lighter and more flamboyant productions of the 1990s. Harris is still clearly shaken by his time abroad. He says of his time in Sierra Leone, “The Revolutionary United Front came in and cut off people’s hands, indiscriminately, women and children. And they’d fill bags with the hands.” In Myanmar, he was exposed to the violent oppression of Rohingya Muslims by Buddhist factions, and he climbed into the small cage where one man had been tortured and held captive. He was so rattled by the sheer vulnerability of working as a documentarian in such a contested terrain that when he came back to Salt Lake he was overcome by numbness on the left side of his body.

Trent Harris, still from Luna Mesa, 2011. HDV, color, 60 minutes. Courtesy of the artist. © Trent Harris.

Despite its rather sci-fi title and crime fiction set-up, Luna Mesa is Harris’s most personal film to date and is a clear attempt to work through these devastating experiences. The film was shot in multiple locations across the globe, often piggy backed onto Harris’s other projects, and follows a young photographer whose older lover has died suddenly, leaving behind only a notebook filled with the remnants of a self-administered psychotherapy. Harris abandoned his normal writing process to make this film, combining fiction and documentary formats: “I didn’t really write this…Part of it has to do with process…If you’re creating something, what you’re really doing is pulling random bits of information together and synthesizing it…Then I write it and I go out and try to film it. So I thought, as long as I’m pulling together random bits of information, why write anything?” The film is fractured, dislocated in time and place, visually cobbled together, and extremely sad.

At the darkest point in the movie, Luna discovers graphic footage made by her lover showing men shot and burned in Sierra Leone. Oddly, the audience at the UMOCA screening, a homegrown audience of Harris devotees, could not seem to get comfortable with this shift in tone, despite its continuity with the collaged unfixity explored in previous works. They laughed at inappropriate moments throughout the film, anticipating a satirical distance that wasn’t there. On the contrary, Luna Mesa is the terribly sincere product of someone dunked into the mire of global conflict only to be drawn back to the sheltered purity of Utah. The film borrows explicitly from Dadaist strategies of non-composition, and appropriately so, since Dada was the first art of post-traumatic stress disorder.9 The simple collaging strategy that made The Beaver Trilogy so successful has in Luna Mesa been taken to its logical conclusion and deployed as a means of reassembling a fractured global subject returned to the motherland. The trope of the cave appears in Harris’s most recent film as well, when Luna, dressed like an intergalactic Jane Fonda, cathartically burns her dead lover’s cryptic journal in a cave near Haynesville, Utah, restoring her own subjective autonomy, while her shadow is thrown by the firelight onto the cave wall behind her.

Her dead lover is—how could it not be?—Trent Harris.

Melissa Ragain is an occasional correspondent for X-TRA. Since she last occupied our pages, she has ventured from the sheltered enlightenment of Jeffersonian Virginia to teach art history at Montana State University.