has explored Herman Melville’s epic novel Moby-Dick, concentrating on what the artist has called its appeal as a “mythic vision of America.” For his second solo exhibition on the subject at Carl Berg Gallery in Los Angeles, de los Reyes looks to those notions of heroism that are considered inherent to our national character, allowing the “perennially ecstatic and volatile” Captain Ahab to stand in as a metaphoric double for our country. In his practice, de los Reyes has often looked to the past for artistic techniques with which to explore his subject matter. In these latest works, the decidedly old-fashioned media of red bister on paper and cast bronze are complemented by acrylic paintings on linen and cast resin sculptures.

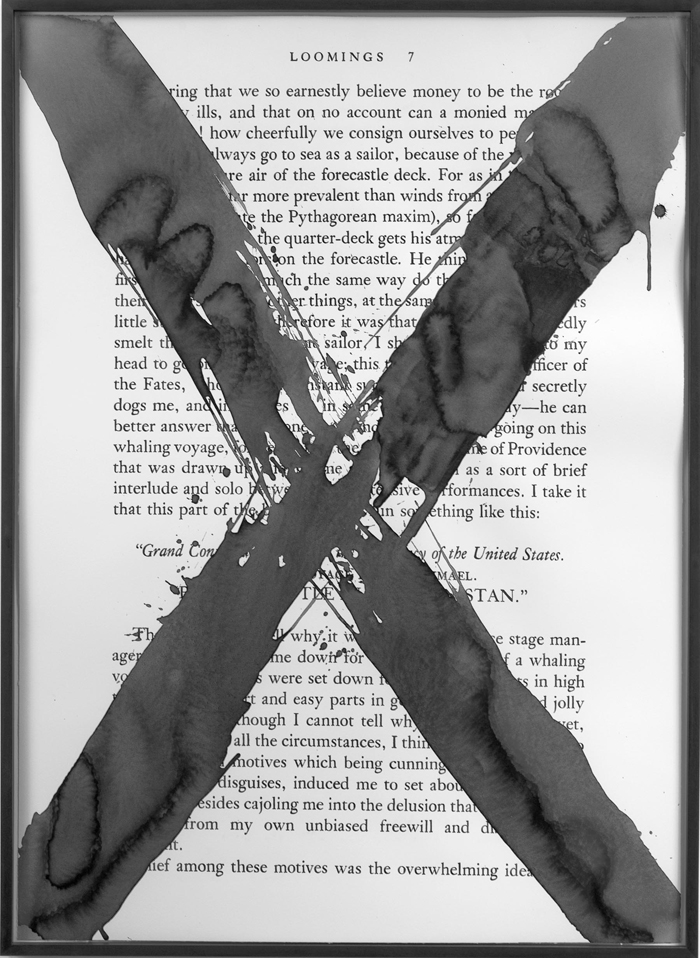

De Los Reyes’s approach to Melville’s epic tragedy is interpretive rather than pedagogical. This proposition, however, belies the viewer’s first impression. Several prominent paintings and works on paper are executed at the same scale as museum didactics and make direct use of book text (excerpted and carefully hand rendered from the artist’s personal copy of the Penguin paperback edition). Consequently, at first they come on strongly like a moralizing lecture. Upon closer inspection, however, it becomes obvious that the words on the surface offer merely one layer of information.

Practically every aspect of Ahab’s America involves a quotation of some sort. In this respect, de los Reyes’s works exhibit the classic characteristics of allegory, in which visual imagery takes on the structure of language to tell stories. This effect extends even to the physical execution of the pieces and his material choices, which nearly always have complex symbolic implications. Art historian and critic Craig Owens noted that the allegorist does not invent images, but “confiscates” them and lays claim to their “cultural significance” in order involve them in critique or commentary.1 With regard to the conditions under which allegorical works hold appeal, English literature scholar Joel Fineman observed that allegory seems to surface “in critical or polemical atmospheres, when for political or metaphysical reasons there is something that cannot be said.”2 Given the waning relevance of the Bush Administration, it seems like a strange time to take up allegory, as all the stops have already been taken out. And yet, most of de los Reyes’s new works are exceedingly compelling. While often quite dramatically rendered, each possesses a subtle tension that restrains it from going over the top. This tension is perhaps most closely characterized as ambivalence and it piques attention. Like Ahab in his famous declamation about the need to strike through the “pasteboard mask” of all visible objects, the viewer is motivated to search Ahab’s America more deeply for meaning.3

Contemporary novelist E. L. Doctorow echoes an often made remark when he says that American literature “begins with Moby-Dick, the book that swallowed European civilization whole.”4 The novel’s appearance in 1851 signaled a turn away from European prose styles and subjects to something unmistakably American, although it would take nearly seventy years for this notion to be recognized by literary critics and for the public to truly embrace it.

Moby-Dick is idiosyncratic: part novel, part philosophical treatise, part natural history lesson, part primer on whaling techniques, with episodic outbursts from a multicultural chorus straight out of Greek tragedy. The author drew from his own experiences at sea, as well as sources as divergent as Virgil’s Aeneid, Shakespeare’s Hamlet and King Lear, Milton’s Paradise Lost, Goethe’s writings on Prometheus, and Shelley’s Frankenstein, among others.5Its plot is based on the true story of the Nantucket whaler Essex, which sunk near the Galápagos Islands in 1820 after being sundered by an enraged sperm whale. Melville conflated the tale of the Essex with the legend of a wily albino sperm whale named Mocha-Dick who traveled the same grounds off the Pacific coast of South America and was finally taken in 1839.

Moby-Dick has been called by some “America’s Rorschach test.” Within the myth of the whale, a vision of the nation can be found.6 Of course, what you divine from its pages can say as much about who you are and what you believe. It has been analyzed to explore a range of national preoccupations, among the most significant being anxiety about totalitarianism, communism, fascism, and Cold War nuclear proliferation; concerns about the pernicious spread of capitalism and its effects on humanity and the environment; and the need to unearth and confront deeply embedded biases about race, class, and homosexuality.

Its very malleability reveals Moby-Dick to be a prototypic “open” text in the sense intended by semiotician Umberto Eco when he examined what he termed “systematically ambiguous” modernist art forms in The Open Work (Opera aperta, 1962). As scholar David Robey explains in his introduction to the English-language edition of The Open Work, a “great variety of potential meanings coexist” in an open work and none can be said to predominate.7The reader is presented with a “‘field’ of possibilities” and is left in large part to decide what approach to take.8 For Eco, real pleasure results when the reader “abandons himself to the free play of reactions that the work provokes in him.”9

This opportunity, however, does not come without certain responsibilities on the part of the writer and reader. Eco wrote the essays that make up The Open Work in reaction against the hegemonic grip that the beliefs of philosopher Benedetto Croce had on intellectuals in Fascist and post-Fascist Italy.10Eco disagreed with Croce’s idealistic characterization of artistic expression as the pure “intuition of a feeling,” as it implied that art has “nothing to do with either morality or knowledge.”11In writings such as “Form as Social Commitment,” Eco sets up openness as resistance to the alienating effects of idealism with its false appearance of continuity and order that can mask a fragmentary, dissociative state of civil crisis.12

During the period when Melville conceived Moby-Dick, the United States was embroiled in crisis. In 1848, the Mexican War ended with Mexico ceding the territories of California, Nevada, and Utah, along with portions of Arizona, Colorado, New Mexico, and Wyoming. The discovery of gold in California later that same year intensified westward migration. By 1850, California’s petition to enter the Union as a “free state” threatened the tenuous equilibrium of the Missouri Compromise, an agreement made to partition the country into free and slave-owning states.

Melville was not personally immune to national politics. His eldest brother Gansevoort, an outspoken proponent of the expansionist doctrine of Manifest Destiny, played an instrumental role in the 1845 election of President James Polk, under whose leadership the nation would first acquire the Oregon Territory from the British and would later annex the Republic of Texas—an action that would lead directly to war with Mexico.13 Melville’s father-in-law, Judge Lemuel Shaw, angered Northern abolitionists when he enforced the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, a law he found morally repugnant yet incontrovertible, instituted as it was to forestall a civil war that leaders from both sides of the slavery issue felt was immanent.14Moby-Dick and the American 1848.”s defiant rejection of God or Ishmael’s wanderlust, propelled by alienation from society. But if we were to imagine a role for Tony de los Reyes aboard the Pequod, it is doubtful that he would be like the vengeful Ahab or the all seeing but non-committal Ishmael. More likely, he would resemble the First Mate Starbuck, a moderate pragmatist who understands very well the stakes in capitulating to Ahab’s obsessive, fatally flawed agenda and ultimately does nothing to stop it. (In the post-9/11 social climate, this role may be one that is quite familiar to many of us.)

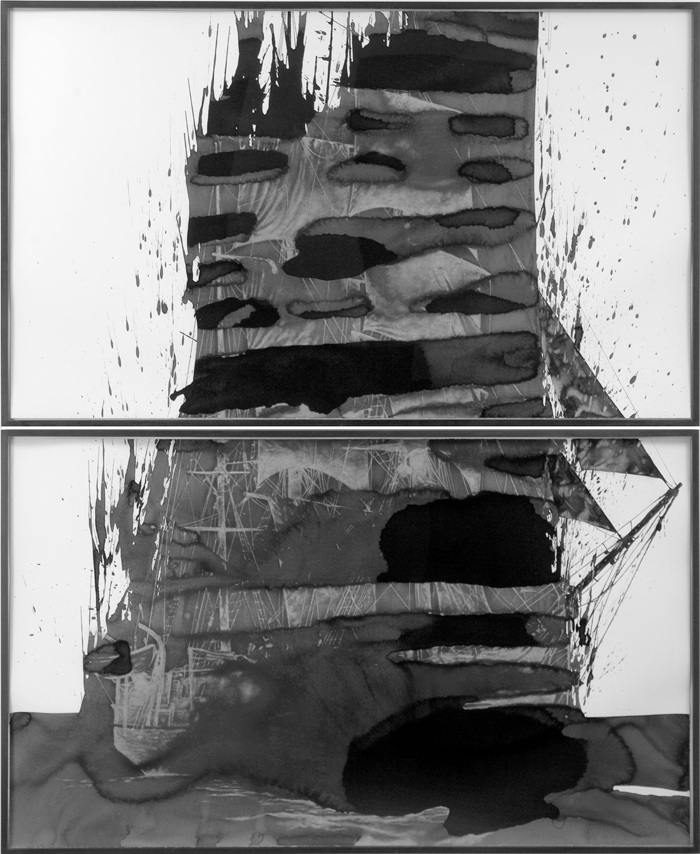

In several works on paper, de los Reyes goes back into the Rorschach-like blots of bister to extract drawings from its surface. He gets under the skin of the pigment by gently abrading it with a water-filled airbrush that also serves as a stylus. These detailed yet soft drawings look like blurry photographic negatives. The visual effect of these skillful, sepia-tinged renderings of whaling scenes serves to expose the romantic understructure of Abstract Expressionism, whose practitioners looked to a far horizon of our cultural narrative for a path to circumnavigate the still-fresh disasters of the early 20th century.

In one such work, Scars and Scraps (2008), de los Reyes depicts the Pequod’s mastheads, lonely roosts where spotters spent long hours scanning the sea for whales. The title proposes an assonant echo of the familiar “Stars and Stripes”, the name for the emblematic American flag. It could be that the trope-like “scars and scraps” refer to cherished remnants of nation building. Incomplete and distorted by time and re-telling, the narrative of these remainders fails to reveal the whole truth about our history and character.

In Chapter 35 of Moby-Dick, “The Mast-Head,” Melville likens the spotters to young philosophers, “romantic, melancholy, and absent-minded” Platonists who lose their identity, having been lulled into an “…opium-like listlessness of vacant, unconscious reverie.”21 By linking the vigil on the mastheads to symbols of patriotism, de los Reyes may be suggesting that those who keep watch for our country can become dangerously and unquestioningly mesmerized by the “truth and beauty” of national ideals. Melville ends “The Mast-Head” with a note of caution for the young dreamer:

But an inch; slip your hold at all; and your identity comes back in horror. Over Descartian vortices you hover. And perhaps, at mid-day, in the fairest weather, with one half-throttled shriek you drop through that transparent air into the summer sea, no more to rise for ever.22

Scars and Scraps is related by title to the imagery of Wake (2008), a cluster of fallen, blue cast-resin stars that lay on the gallery floor. One of the more conspicuously allegorical works in de los Reyes’s series, it presents the embroidered pentacles of the U.S. flag in three-dimensional form. Wake suggests both the trail of destruction left behind the hard-driving “War on Terror” as well as a memorial to mourn those youths who have willingly sacrificed themselves for the cause.

A single white bronze star stands in for the narrator of Moby-Dick in Ishmael (2008). The same white star makes its next appearance clenched between the teeth of an overturned skull in Ahab (2008). In Melville’s “Ahab” (Chapter 28), the dreaded captain mounts the quarterdeck for the first time. Ishmael describes him as looking “like a man cut away from the stake, when the fire has overrunningly wasted all the limbs without consuming them, or taking away one particle from their compacted aged robustness.” Despite such fearsome physical attributes, Ahab’s mien is still classically heroic. His “…whole high, broad form seemed made of solid bronze, and shaped in an unalterable mould, like Cellini’s cast Perseus.”23

Quite tellingly, de los Reyes has cast Ahab and Ishmael from the same bronze. Underneath their surface aspects, they represent two close points along a continuum of quintessentially American characteristics. The deathly, patriarchic Ahab is cannibalistically insatiable, while native son Ishmael, eager for adventure, readily accepts his own potential sacrifice. As disturbing as Ahab may be, de los Reyes does not assign blame with this work. Nor, however, does he exclude himself from the justifiably troubling implications in the entirety of Ahab’s America.

Artists who take upon themselves the role of social commentary must contend with an underlying idealism that steers them unfailingly toward return to a mythic orderly universe. The challenge to charting another course is complicated by the nature of language. Umberto Eco has commented that in time of crisis, “…language, having already done so much speaking, becomes alienated to the situation it was meant to express.”24 The artist who wishes to address the condition of crisis must also recognize that “if he accepts this language from within, he will also alienate himself to the situation.”25 The artist often seeks to rectify his dilemma by “dislocating language from within,” in a bid to “escape from the situation and judge it from without.”26 But bonds of language are inescapable:

I violate language because I refuse to express, through it, a false integrity…but by doing so, I can’t but express and accept the very dissociation that has arisen out of the crisis of integrity and that I meant to dominate with my discourse. There is no alternative to this dialectic. …All the artist can hope to do is cast some light on alienation by objectifying it in a form that reproduces it.27

Believing that desirable solutions to crises must ultimately arise from collective enterprise, Eco proposes that each work of art be “open” in the same sense that debate is “open”28 and allow for numerous interventions on the part of its viewers. Art suggests “…a way for us to see the world in which we live, and, by seeing it, to accept it and integrate it into our sensibilities.”29By opening a work up to an unlimited range of possible readings, the artist disrupts its idealistic impetus towards continuity. It is in discontinuity that the possibility of a “unified, definitive image of our universe” is called into question.30 A similar dynamic is at play in allegory, which, by its fragmentary nature, offers an “antidote to the totalizing impulses of art.”31

In Ahab’s America, Tony de los Reyes engages several artistic forms as means to think about and learn from his relationship to his subject. Speaking to viewers through quotation, his allegories serve to confess his inability to disentangle his subject and its critique from the legacy of his artistic and literary predecessors, as well as that of the collective American imagination. Those notions of Yankee might, ingenuity, and freedom born of the 19th century—and that suffuse Moby-Dick—are still pretty heady stuff. It is difficult not to become intoxicated by the novel’s prose even when your approach is critical. But you cannot return to a place that never existed, even in Melville’s time. Indeed, an acknowledgment of this false legacy and its seductiveness becomes a meta-textual motif of Ahab’s America. In the polysemic volley between form and commentary about form, de los Reyes provides his viewers with an opportunity to engage in the kind of free play that Eco advocates.

Clearly, to Tony de los Reyes, our past legacy (and its implications for the future) is as terrifying as it is romantic. Lately, a great number of truly tragic and destructive actions have been perpetrated in the name of our national interests. In our current international conflicts, we Americans all are without doubt or exception complicit. As we prepare to enter a potentially new sociopolitical era, it seems appropriate to reconsider openness as a basis for introspection and action.

Kristina Newhouse is curator of the Torrance Art Museum.