Monsters have always defined the limits of community in Western imagination.

–Donna Haraway1The new world of monsters is where humanity has to grasp its future.

–Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri2First things first I’ll eat your brains / Then I’ma start rocking gold teeth and fangs / Cause that’s what a muthafucking monster do…

–Nicki Minaj3

Mario Ybarra Jr.’s recent exhibition, Double Feature, consists of two projects: Universal Monsters and Scarface Museum. While Scarface Museum made its debut at the 2008 Whitney Biennial, this essay will primarily address the other “feature” headlining in Wilmington artist Ybarra’s first showing at Honor Fraser. It is here, in Universal Monsters, that Ybarra grapples with the complicated and often conflicted project of self-imagining. Ybarra’s paintings and ceramic sculptures reference Hollywood films, such as The Invisible Man (1933), The Creature from the Black Lagoon (1954), and American Werewolf in London (1981). His literary references include Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man (1952), and H.G. Wells’s The Invisible Man (1897). Ybarra’s video, Transformer (2013), pays a debt to Michael Jackson’s pop song Thriller (1982) and the eponymous video from 1983, directed by John Landis. Drawing upon these and like sources, Ybarra’s self-portraits identify less with the hero or the villain than with the unseen, the outcast, the pariah, the misunderstood, and the alienated. Yet they are not self-loathing; these self-portraits are both less than alter egos and more than commentaries on monsters as one’s (and one’s culture’s) other-selves. Collectively and importantly, Ybarra’s creations parade before the viewer presentations of himself that linger somewhere between their formation in response to material, psychic, and sociopolitical conditions and those personas that he imagines, shuns, desires and/or with which he perhaps seeks affinity.

In Ybarra’s “monsters,” the artist’s self-reckoning makes visible a vast terrain of identities that are at once bitingly humorous, melancholy, assertive, empowering, and absurd. The works trace the contours of “the fragile borderline (borderline cases) where identities (subject/object, etc.) do not exist or only barely so—doubly, fuzzy, heterogeneous, animal, metamorphosed, altered, abject,” to borrow and transpose Julia Kristeva’s notes on literature.4 In the dimly lit, grey-walled gallery, Ybarra’s paintings and sculptures allow a glimpse of an unsettling politics of self-scrutiny by placing the viewer in a space between conflicting personalities or seemingly opposing forces. When situating the work in a larger context of the artist employing her/his likeness, Ybarra’s work offers an opportunity to consider that precarious and always fragile borderline around artistic identity formation.5

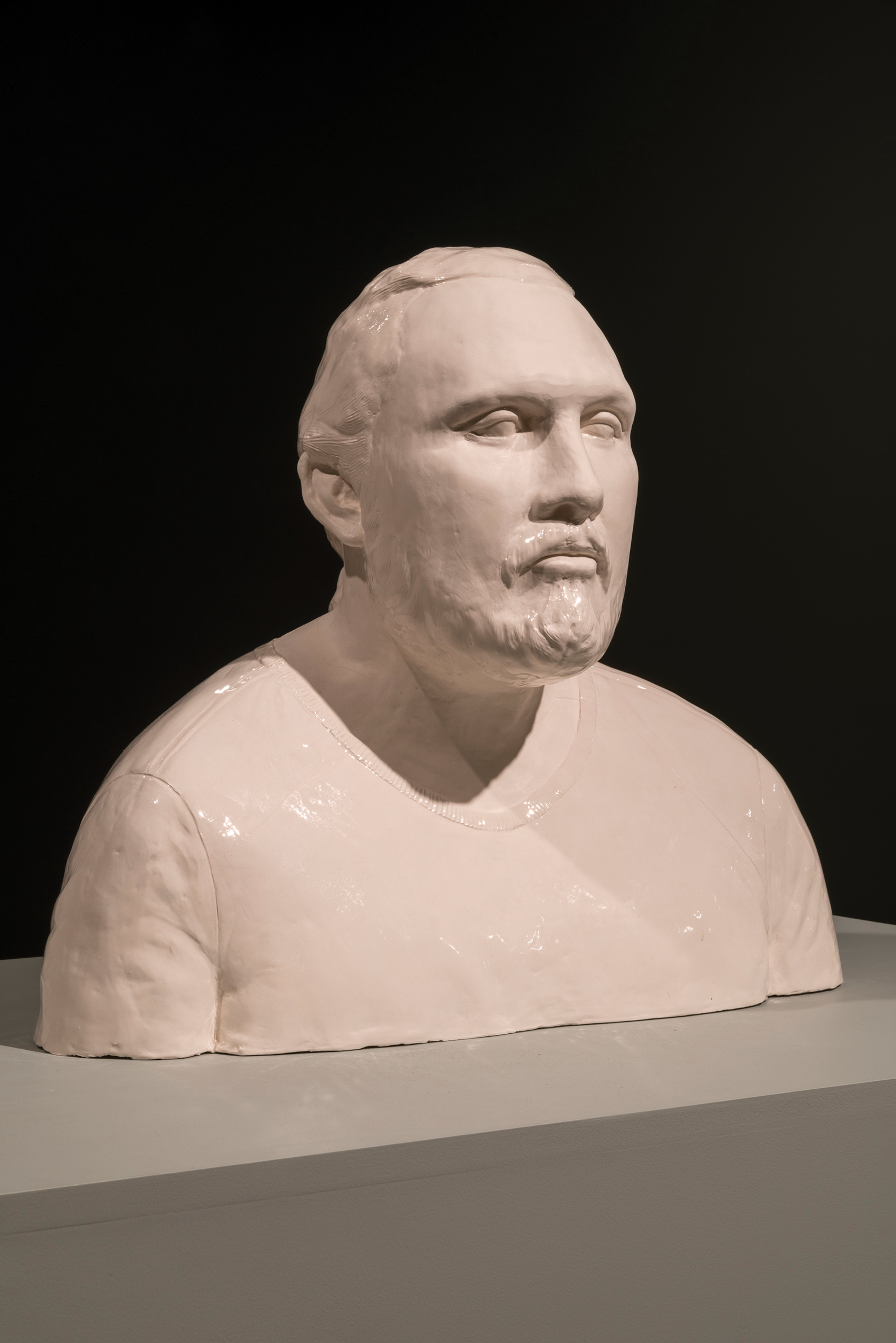

Mario Ybarra Jr., Dr. Jekyll…, 2013. Porcelain with white glaze, 20 × 20 × 10 inches. Edition of 3 + 1AP. Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery. Photo: Josh White/JWPictures.com.

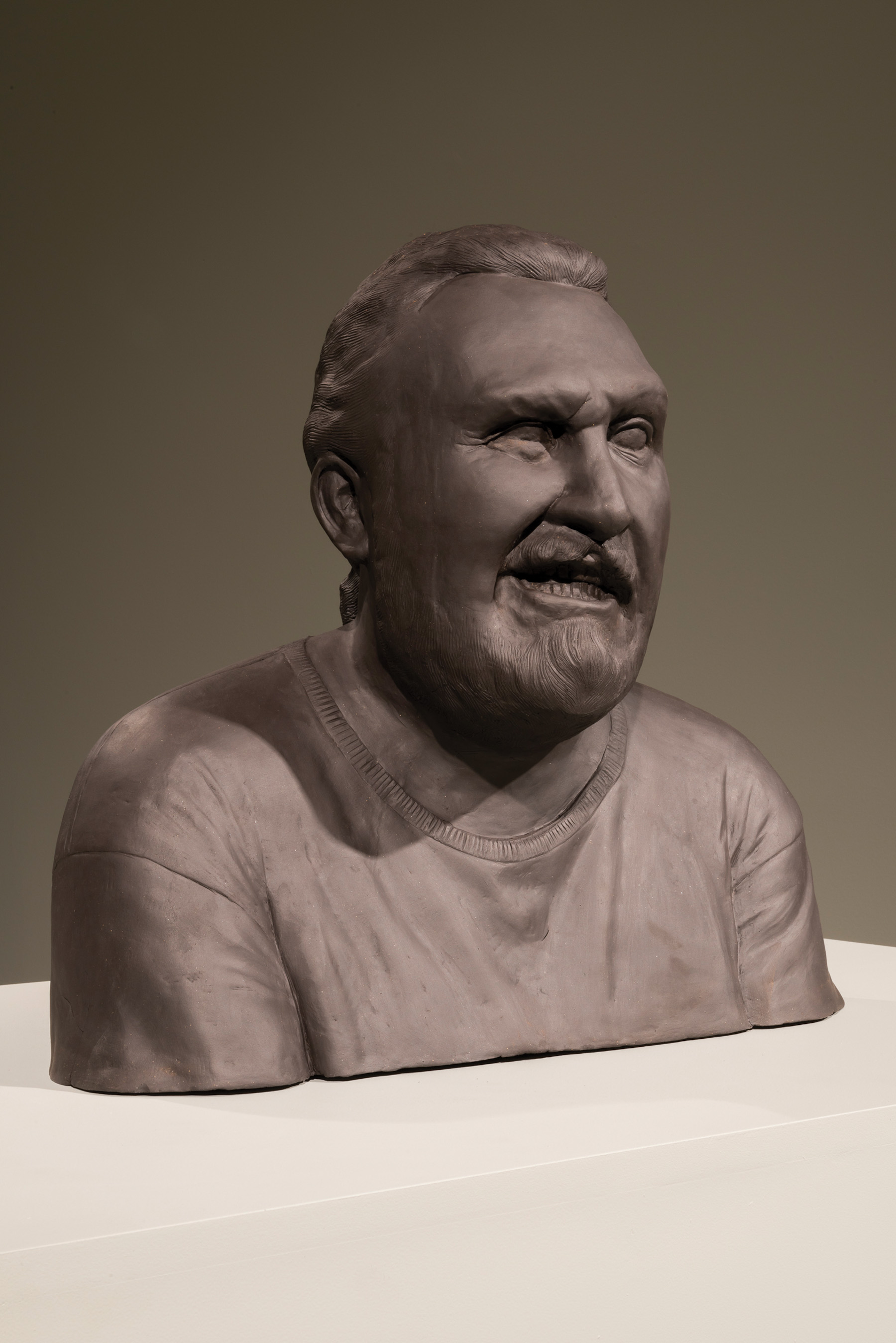

Two larger-than-life porcelain busts, Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde (both works, 2013), occupy opposite edges of the gallery. Each is cast in a muted monochrome glaze—white and black respectively. Similar to Robert Lewis Stevenson’s late nineteenth century novella, The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, Ybarra creates a double portrait based on the psychological extremes of one subject. Whereas the novella gives the reader closure, ending with the demise of “the evil” Mr. Hyde at the self-sacrificing hands of the “good” (but “unhappy”6) Dr. Jekyll, the viewer standing in Ybarra’s exhibition is located between the busts’ arrested processes of psychosomatic transformation where the irresolution provides no suitable or sustainable identity to embrace or reject. The pale white portrait bust of Dr. Jekyll is drained of life while the dark and grimacing Mr. Hyde is a caricature of wickedness. What does it mean for the subject when the clearest polarities of the self are so uninviting, unsustainable, and uninhabitable?

Mario Ybarra Jr., Mr. Hyde…, 2013. Porcelain with white glaze, 20 × 20 × 10 inches. Edition of 3 + 1AP. Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery. Photo: Josh White/JWPictures.com.

In the painting Invisible Man (2012), Ybarra shows himself, from the chest up, staring steadfast and somberly ahead. Bespectacled, goateed, wearing a crisp black V-neck, and cloaked in a beige balaclava and floppy cap, the figure mixes and matches a host of representations gleaned from art, politics, cartoons, movies, television, and novels. For example, Ybarra paints an homage to the unnamed narrator of Ralph Ellison’s novel, Invisible Man, shifting the subject from an African American to a Chicano/Latino, which, along with rendering the figure only partially visible, reminds the viewer of the repeating historical patterns of the politics of identity. In this sense, Ybarra’s figure both visualizes and reframes Ellison’s narrator’s assertion: “When they approach me they see only my surroundings, themselves or figments of their imagination, indeed, everything and anything except me.”7

Mario Ybarra Jr., Invisible Man…, 2012. Acrylic on canvas, 60 × 48 inches. Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery. Photo: Josh White/JWPictures.com.

Like Ellison, Ybarra has never been concerned with simply enacting a polemical relationship with those who engage the work. Ellison’s protagonist also reminds the reader of the potential and limits of invisibility: “I am not complaining, nor am I protesting either. It is sometimes advantageous to be unseen, although it is more often rather wearing on the nerves.”8 Harnessing invisibility, if not self-imposed anonymity, can be used as a force against restrictive and oppressive powers, a tactic employed by the Zapatista spokesperson Subcomandante Insurgente Marcos, whose masked faced and capped head Ybarra’s Invisible Man evokes. Closer to home, Los Angeles artist Sandra de la Loza has also presented herself wearing a beige balaclava, adding a gunlike drill.9

In a gallery discussion, Ybarra remarked that the popular culture version of the Invisible Man, the masked one with hat and sunglasses, was his favorite childhood Halloween costume. Unlike expensive, stock store-bought costumes, Ybarra noted that this costume could be creatively put together from household materials, an ease that allowed him to recreate himself year after year as the Invisible Man to go trick-or-treating unseen.10 That Ybarra’s subject in the painting is the adult version of himself dressed as the Invisible Man gives a glimpse of a much more complex self-portrait.

Thus, while the issue of class and childhood self-fashioning underpin the costume choice, painting the adult self, and especially as an ethnically marked adult wearing a ski mask, translates less as a Halloween outfit than as a personification of the disguised figure now associated with terrorism and militancy. The subject’s unwavering gaze appears to cut straight through the unacknowledged viewer, and Ybarra as an invisible man doesn’t evoke his nostalgic longing for childhood play or indicate a frank assessment of the transformation of the self over time. Rather, it functions as a reminder of the injurious consequences of racial profiling and the racism that are part of—and also predate—the ongoing repercussions of 9/11. Wearing the ski mask, Ybarra’s subject, viz. Ybarra himself, demonstrates how easy it is to provoke an encounter with “the strange and the stranger.”11 As viewers we stand alongside Ybarra’s Invisible Man. On one hand, this encounter might simply raise the question: Who is this masked man? On the other hand, it might encourage a more forceful self-reckoning with the unknown and the foreigner. Ybarra’s Invisible Man makes present a central concern in Kristeva’s Strangers to Ourselves, that “the foreigner lives within us: he is the hidden face of our identity.”12 Understanding the foreigner within us is to acknowledge our own “disturbing otherness, for that indeed is what bursts in to confront that ‘demon,’ that threat, that apprehension generated by the projective apparition of the other at the heart of what we persist in maintaining as a proper, solid, ‘us.’”13 In other words, we no longer despise him (or her) for it “turns ‘we’ into a problem, perhaps makes it impossible….”14 Recognizing the hidden and the disturbing within us is no easy task. Ybarra’s Invisible Man, I think, enacts what Kristeva argues is the “experience of the abyss separating me from the other who shocks me.”15 She writes, “I do not even perceive him, perhaps he crushes me because I negate him. Confronting the foreigner whom I reject and with whom at the same time I identify, I lose my boundaries, I no longer have a container, the memory of experiences when I had been abandoned overwhelms me, I lose my composure. I feel ‘lost,’ ‘indistinct,’ ‘hazy.’”16 We are faced with a precarious situation.

Ybarra has frequently constructed such troubling propositions for both himself, as the subject of his work, and for his viewers. Over a decade ago, Ybarra made Go Tell It… (2001), a series of four photographs that depicts a lone figure (Ybarra) amidst left-behind spaces in Southern California. The subjects of the photographs are parts of the submerged city of San Pedro, the artist’s childhood home, a vacated trailer park, and an inoperable World War II military site designed to protect the West Coast from enemy attack. In each, the figure stands, yelling into a megaphone and raising a clenched fist in the air. These gestures are the tropes of the organizer, the leader, the activist, and the artist. By placing this isolated figure in unoccupied spaces leading no one, Ybarra’s Go Tell It… offers a visual conundrum similar to Invisible Man. Who is this fringe figure yelling at and what is he saying? Knowing that the subject is Ybarra might encourage a more productive line of inquiry: What should be told? How should it be told? By whom and to whom?17

Mario Ybarra Jr., Go Tell It… #1, 2001. Color lightjet print, 47 × 59 inches. Edition of 5. Courtesy of the artist and Honor Fraser Gallery.

Go Tell It…, in effect, asks the artist himself as much as the viewer: To whom am I responsible? In this sense, the series serves as an engagement with both the limitations and potential of sociopolitical agency and activism (artistic or otherwise). It reminds the viewer that the urgencies requiring sociopolitical action necessarily carry with them both uncertainty and vigilance. Go Tell It… holds onto an unrelenting commitment to sociopolitical activity despite, or rather because of, the withdrawal of any assembly. Situated in the gallery space, it can also allude to a gathering force beyond the viewers’ purview, thereby implying an assembly to come. As a representational strategy, Ybarra’s photographs maintain a tension between an active reflection on issues of accountability and a reminder that active reflection cannot be effective in isolation; to succeed it must accompany political action.

Go Tell It… and Universal Monsters revolve around a lone figure, though Ybarra has seldom worked alone or in a studio artist’s typical isolation. At Honor Fraser, an unseen presence—a collaborative dimension of Ybarra’s practice—gives shape to the monsters in the exhibition. Shortly after the completion of the Go Tell It… series and up through the current production of Universal Monsters, Ybarra has been working collaboratively with the artists Juan Capistran and Karla Diaz. Curator Rita Gonzalez described their project, Slanguage, as “a combination studio, site for guerrilla education, and exhibition space,” and eloquently explained the ideas at work within the name: “The neologism ‘slanguage’ suggests a mutation of common speech—a street-level transfusion. This new formation is born out of an aural and pictorial sensitivity to noise. Ybarra and Capistran translate and generate street-level articulations (of mixed identity, of urban sampling, of altered forms of popular culture), and as such, both artists function as the lexicographers of this new Slanguage.”18

While collaboration does not have a visible presence in Universal Monsters, it can be felt and heard. Ybarra is the first to give ample credit not only to Capistran and Diaz (Ybarra is also married to Diaz), but also the extensive network of artists, writers, activists, students, and friends that generate projects and processes in and outside of Slanguage. Something is always under construction, under destruction, and underway at Slanguage, where the works in Universal Monsters were produced. There, stories, fears, fantasies, and fictions were transformed and given a material presence in the form of porcelain, painting, and a video. What part did collaboration play in the production of this body of work? How might the collaborative process challenge the viewers’ conception of a self-portrait? What does it mean to contribute monstrous attributes to another’s self-portrait? Or is this no longer a self-portrait but more a result of projecting the other within us onto another? And, does Ybarra’s work open a space for understanding subjectivity as multi-constructed? Perhaps a more vexing question, one facing many collaborative procedures, is how to render visible multiplicity, collectivity, and heterogeneity.

Mario Ybarra Jr., Invisible Man… No. 2, 2012. Acrylic on canvas, 60 × 48 inches. Courtesy Honor Fraser Gallery. Photo: Josh White/JWPictures.com.

In Universal Monsters, a phantasmal presence—the face—is nearly ever-present. The face that Ybarra shows the viewers is, as with most Hollywood monsters, far from self-satisfied. Sometimes it is racked with anxiety, fear, frustration; at other times it is melancholy, withdrawn, and dismissive. Only one work, Invisible Man… No. 2 (2012), is different. One of the first images encountered upon entering the gallery, located directly across from the fully visible Invisible Man…, Invisible Man… No. 2 is a large, pristine canvas with what appears to be the same pair of glasses and hat as its counterpart. However, the subject is elsewhere. While the illusion of the face is suggested, the animating body within remains absent, rendering the subject invisible. The left-behind glasses resting on the flattened hat are all that remain. While looking at Invisible Man… No. 2, I could not help but recall René Magritte’s The Treachery (or Perfidity) of Images (1928–29), with its briar pipe perched above the painted phrase Ceci n’est pas une pipe. The sparseness of Ybarra’s canvas and the meticulously rendered subjects, and perhaps my being a too disciplined art historian, invoked for me the association with Magritte’s painting, which cautions viewers not to mistake the painted image for the object represented. Similarly, Ybarra’s self-scrutinizing series of self-portraits asks viewers to think carefully about what they face when standing in the presence of Universal Monsters.

Mario Ontiveros is a member of the X-TRA Editorial Board and teaches in the Art Department at California State University, Northridge.

For reading earlier versions of this review and giving insightful comments and suggestions, I would like to thank Rebecca Bernard and Ellen Fernandez- Sacco.