The largest image in the exhibition Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A. at the MOCA Pacific Design Center greets visitors with an inviting smile as they scale the stairs to the second floor. A youthful Joey Terrill, circa 1975, models one of his maricón (Spanish slang for faggot) t-shirts as he lies supine, his eyes softly returning our gaze. Terrill, who is one of the artists in the exhibition, also fabricated malflora (bad flower, slang for dyke) shirts; both versions featured hand-painted text on soft yellow cotton and the words role model on the back. He self-presents as at once macho (that mustache) and soft (his posture and expression). The image suggests ambiguous intimacy with the person behind the camera—Teddy Sandoval, another artist in the show. The image has the feel of a private snapshot, yet also functions as documentation of an artwork (the t-shirt) and as publicity to build interest for more potential wearers (as seen in the catalog’s cover photograph of a line of men and women wearing these shirts at the 1976 Christopher Street West pride parade). The image appears not as an original print but as a blown-up wall adhesive, significantly larger than life size. I open with this image not only because it’s crush-worthy but also because it scales in and out of so many of the show’s themes: social networks, self-fashioning and performance, language, publicity, and genre ambiguity.

Featuring 50 artists and collectives, Axis Mundo incorporates a range of mediums that reflect the resourcefulness and eclecticism of queer Chicana/o art practices of the 1970s to early 1990s: painting, photography, drawing, video, conceptual art, mail art, zines, punk music and flyers, apparel, mixed media, and more. This was a dynamic scene, with some artists exploring and evolving through a range of mediums and others moving away from art practices. Axis Mundo was co-curated by C. Ondine Chavoya and David Evans Frantz as part of the Getty’s Pacific Standard Time: LA/LA initiative, and the exhibition occupies two venues (MOCA Pacific Design Center and the ONE Gallery).1 The installations share artists, and a mixture of media appears at both sites, with the ONE space more oriented toward smaller-scale works, presented salon style and in vitrines. Although the exhibition does present thematic clusters of works with discrete wall text, the open plan of each of the spaces produces an effect wherein the eye mingles them. Works on paper in vitrines visually reverberate with paintings, fashion, and video across the room, giving the installations an effect of hyperstimulation that facilitates connections and undoes distinctions.

Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., installation view, MOCA Pacific Design Center, West Hollywood, September 9–December 31, 2017. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. Photo: Zak Kelley.

The exhibition at once expands outward from figures and practices in Chavoya’s essential 2011 Pacific Standard Time: Art in L.A. 1945–1980 exhibition Asco: Elite of the Obscure, which he co-curated with Rita Gonzalez for the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA) and has brought more artists’ papers and works into ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archive’s collections.2 Reflecting its archival affiliation, the exhibition entailed a process of searching through personal connections and collections. Much of the work in the show has not been publicly exhibited since it was first made—if ever at all. The curators looked through the apartments, garages, and storage spaces of the lovers, friends, and families of artists who have passed and through the papers of artists at archives. The research also involved looking through the collections of non-Chicana/o artists at museums in order to find works—particularly mail art and print media—that circulated beyond Los Angeles. Part of what makes the exhibition and the creative milieus it represents queer—in terms of refusing reductive identity categories—is that the artists and their affinities are neither homogenously gay and lesbian, nor all Chicana/o, thereby complicating the very categories of identity that undergird its organizing framework.

Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., installation view, MOCA Pacific Design Center, West Hollywood, September 9–December 31, 2017. Courtesy of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, and ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. Photo: Zak Kelley.

This exhibition enacts the core investments Karen Mary Davalos identifies in her recent scholarly book Chicana/o Remix: its curators excavate unseen works and take an anti-binaristic approach to identity and genre. In addition to the exhibition’s panoply of mediums and identity positions, its constitution rejects divisions between strictly policed ethnic identities and claims toward “universality”—the latter a common and pandering codeword taken up by critics who do not identify with representations yet want to explain why they find them resonant. The use of the gendered Chicano in the exhibition title—rather than the gender-inclusive Chicana/o and Chican@ or non-binary Chicanx—reflects the fact that the work is majority gay male, though the exhibition has brought attention to debates about the gendering of the Chicana/o/x terms (most notably in an article in The New York Times).3 The term Chicanx would be anachronistic for the works in this show. The curators have, nonetheless, highlighted collaborations between these men and women—such as Patssi Valdez’s work with and beyond Asco, as well as the band Nervous Gender—and important contemporaneous work by queer Chicanas Judith F. Baca and Laura Aguilar. This exhibition likewise presents no cleavage between political art that offers a militant critique and cultural art that reflects experience; for these queers, politics and culture are inextricable—and even more so with the expansion of the AIDS epidemic. Finally, the PST: LA/LA endeavor as a whole demonstrates the continued and necessary work of representation.4

The Chicano movement and gay liberation blossomed concurrently, influencing and involving a number of these figures as early as high school. A group of queer Chicano students at Cathedral High School in Los Angeles even took up the name Las Escandalosas (the scandalous girls). A series of 1970s exhibitions of Chicana/o art began to articulate this generation of artists as sharing a project or even a movement. The exhibition and its catalog’s essays foreground the role of institutions, such as schools (Otis Art Institute, Cal State University-Long Beach, Immaculate Heart College, East Los Angeles College), artists’ spaces (LACE), grassroots organizations (Gay and Lesbian Latinos Unidos and VIVA), bars and parties (Gay Funky Dances, Circus disco, and the Butch Gardens, Score, One Way, and Plush Pony gay bars), and the postal service. Queer Chicana/o art was realized through shared social spaces, student groups, institutional critique, and invented publications, collectives, and imaginary institutions (such as Teddy Sandoval’s Butch Gardens School of Art and Jack Vargas’s Le Club for Boys). These latter projects reflect the logics of Jerry Dreva’s Les Petites Bonbons, a conceptual glam rock band that produced publicity but not music, and Asco’s famed No Movies, stylized publicity stills for films that did not exist. Postcards of the No Movie stills (effectively dime store photo prints) in turn circulated as both mail art and as publicity materials—and both iterations figure in the exhibition. Such voracious conceptual and social practices not only reflect the structural need for Chicana/o artists to be resourceful and collaborative when the white art institutions offered little recognition or support for them but also illustrate these young artists’ own questioning and reimagining of what forms art might take and where it might live.

Axis Mundo takes its name from the social and artistic networks that proliferated from the artist Mundo Meza, whose striking Self-portrait (1983) appears in the first room of the installation at MOCA Pacific Design Center. The vibrant painting contrasts with his monochromatic paintings—which are alternately more fantastical and abstract—also on display. His colorful self-figuration appears to be pushed to the left edge of the frame, exceeding its borders, and exists in tension with the literal whiteness that occupies much of the image. Rather than suggesting an unfinished quality, the broad streaks of white paint envelop the figure, so that he begins to disappear. He impassively looks just beyond us. Brushstrokes (one black, one white) obscure his irises, and streaks of black paint to his left (our right) suggest an unresolved abstraction or a figure who has not yet taken form. One might project metaphors of race or AIDS wasting onto the whitewashing or disappearance, respectively, of his body.

Mundo Meza, Self-portrait, 1983. Acrylic on board, 48 x 48 in. Gift of Gera Korte. ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. Courtesy of Pat Meza. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

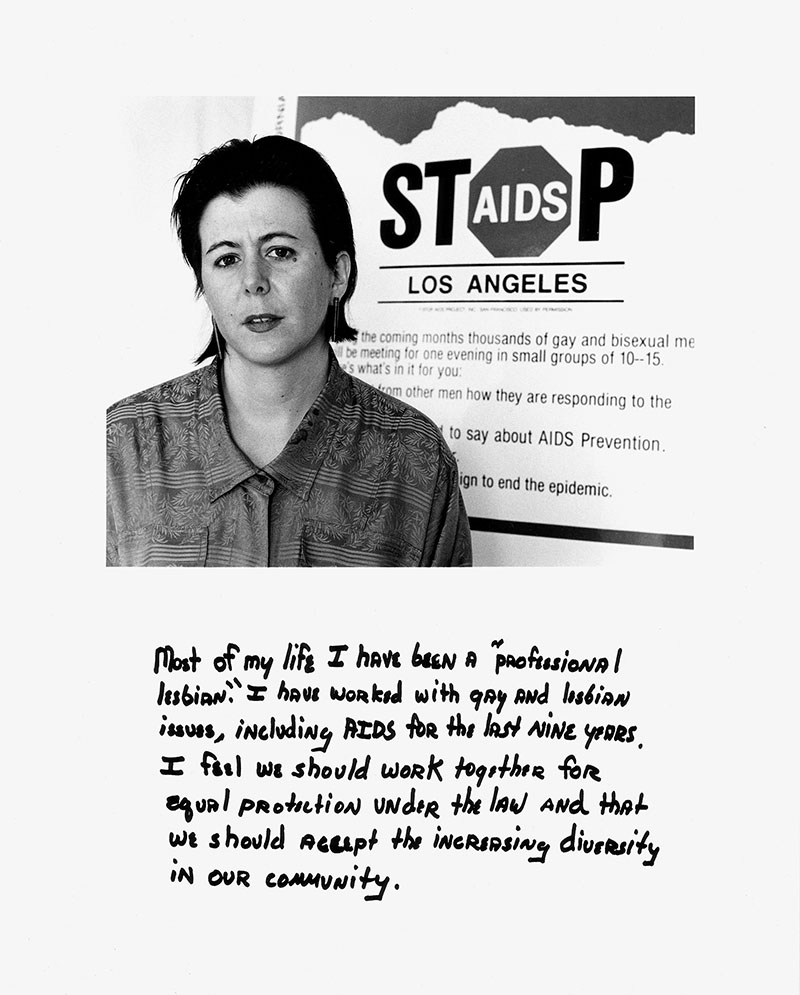

Although the title Axis Mundo references Meza, the Spanish word mundo translates into English as world. Decentralized networks do not operate from a single originary node or in a linear trajectory, and Meza’s work, though recovered through this exhibition, does not present its only axis. Gronk, notably, connects numerous artists here: as an early friend and performance collaborator with Meza and Cyclona (Robert Legorreta); as a lover and mail art collaborator with Jerry Dreva of Les Petites Bonbons; as a founding member of Asco, with Harry Gamboa Jr., Willie F. Herrón III, and Patssi Valdez; as a founding member of LACE; as a friend and mail art correspondent with Teddy Sandoval; and as a backdrop painter for Nervous Gender. Beyond the generation and scenes that form the show’s core network, Laura Aguilar studied with Judy Miranda, participated in VIVA, and has been exhibited alongside a number of these artists elsewhere. Her two included photo series, the Latina Lesbians series (1985–91) and the Plush Pony series (1992), both at MOCA Pacific Design Center, present powerful images and stories of self-definition and affectional community.5 In the Latina Lesbians series, Aguilar presents black-and-white portraits of individual women above the women’s own handwritten statements of self-definition; the Plush Pony series presents women, mostly in poses of embrace, taken at the titular East Los Angeles Chicana lesbian bar.

Laura Aguilar, Judy, 1990. From the Latina Lesbians series, 1985–91. Gelatin silver print, 11 x 14 in. Courtesy of Laura Aguilar.

The AIDS epidemic, which has disproportionately impacted men who have sex with men, communities of color, and the intersections thereof, haunts the exhibition—as it must: a number of the artists in the show died young or continue to live with HIV. For me, two of the most moving works in the exhibition reflect the queer kinship between gay men and the women who became their caretakers, fellow activists, collaborators, and friends. A Southern California native raised by a Chicana activist, Ray Navarro was active as an art student in Los Angeles during the 1980s. In 1988, he moved to New York, and he has become known for his participation in ACT UP/ New York. He seroconverted soon thereafter and conceived Equipped (1990) to ironically eroticize his sick body. By this time, Navarro had gone blind, so he enlisted his friend Zoe Leonard to photograph his mobility devices and fabricate the work. Equipped appears in MOCA Pacific Design Center as a triptych with three framed black-and-white photographs, in Leonard’s characteristically affectless style, of Navarro’s overturned wheelchair, his toppled walker, and his inverted cane. Below the photographs hang institutional-style faux woodgrain placards engraved with “HOT BUTT,” “STUD WALK,” and “THIRD LEG,” respectively. The photographs appear devoid of people, so that the double entendres of the signage fetishize these technologies of disability as sex toys. The absence of Navarro’s figure also has a ghostly effect: these objects would remain after he had passed. He died at age 26, in the same year the work was conceived but before it was exhibited publicly. But I like to imagine him and Leonard cackling as they came up with an obscene list of potential phrases to use in the work.

Installed near Equipped, Judy Miranda’s Mother (1983) dates from early in the epidemic. A close friend—nicknamed “mother” by friends for his maternal personality—enlisted Miranda to photograph his erogenous zones as a gift for his lover. Six framed photographs—four in a vertical column, one on either side—form a cross. Each frame presents a small square black-and-white photograph of a body part: nipple, belly button, armpit, penis, etc. The work evokes dual intimacies, including the trust he felt in Miranda and the body he offered to his lover. The work, like many others in the show, questions the distinctions between art for public view and private communication. The last time Mother was displayed was at the subject’s funeral.

Ray Navarro (fabricated by Zoe Leonard), Equipped, 1990. Three gelatin silver prints with plaques; photographs: 12 3⁄8 × 18 5⁄8 in., 12 1⁄4 × 18 1⁄2 in. and 18 5⁄8 × 12 3⁄8 in.; frames: 20 × 24 in. each. Collection of Patricia Navarro. Courtesy of Patricia Navarro. Photo: Zak Kelley.

Another artist who queered conceptual art by foregrounded desire, Jack Vargas worked primarily with language as his medium. He produced lists and prose; professionally he was a librarian. His major work in Axis Mundo, The New Bourgeois ‘I Want’ with Gay Male Suggestiveness (c. 1976–79), presents a list of desires—for real estate (Vargas was from Orange County), men, and status, such as:

I want to have intelligent people over.I want them to notice.

I want them to be impressed.

I want to be impressive.I want to make an impression.

Later, he states, “I want a ‘Chic’-ano.” Vargas was friends with Terrill and Sandoval, among other artists in the show, but came to this scene with a more privileged background. His work pushed back at the class and progressive political assumptions of what Chicana/o art should celebrate by offering contradictory pleas for being taken seriously and for shallow material gains. The lengthy piece at times circles in on itself, reflecting the complexity and illogics of desire, while, as an open-ended work that spanned several years, suggests that desire can never ultimately be satisfied.

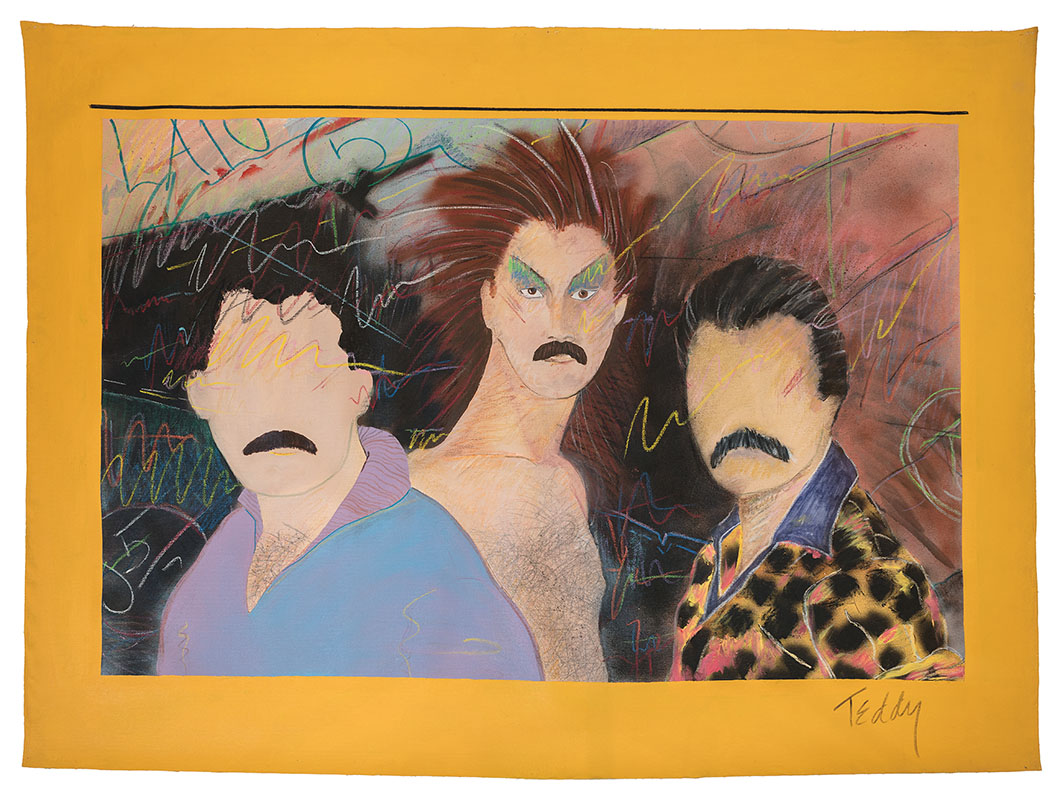

Teddy Sandoval’s Las Locas (c. 1980) has appeared as one of the primary publicity images for the exhibition. The work, acrylic and mixed media on unstretched canvas, presents a trio of male figures sporting gay clone mustaches and chest hair, seemingly at a disco. The central figure—the only one with facial features—sports Divine-style eye make-up and a flaming, teased blow-out. Multicolored crayon squiggles evoke the lights of a dance floor and date the work with an early 1980s aesthetic. The title—translating as “the crazy women”—suggests gender-inverted camp identifications and solidarities with a flair for histrionics. Thus, the image’s play with gender performance, communal spaces, and medium hybridity reflect the larger modes of the exhibition. This painting presents the nightclub as a space of fantastical self-invention and solidarity, as well as illustrates the kinds of imaginary institutions—Sandoval’s Butch Gardens School of Art and Vargas’s Le Club for Boys—that these artists conceived.6

Print publications, mail art, and show flyers—works that circulated internationally—importantly comprise much of the show. This printed matter, which made its way to art and punk figures in Canada and the United Kingdom and to artists in Latin America, connects Axis Mundo to the world beyond the United States. These materials are arguably better served by their generous reproduction in the catalog, which allows the kind of sustained engagement not afforded by its presentation in plexiglass vitrines. The catalog also reprints primary documents, such as Vargas’s complete New Bourgeois, which also was available as a printed takeaway in the gallery; Nervous Gender concert flyers; Gerardo Velásquez’s poetry; Ray Navarro’s essay “Eso, me está pasando” (1990); and a retrospective afterword by Meza’s lover and collaborator, Simon Doonan.

ONE has emerged as an important and prolific venue for exhibitions and publications since its inaugural show Cruising the Archive: Queer Art and Culture in Los Angeles, 1945–1980, co-curated by Frantz and Mia Locks during the first iteration of the Pacific Standard Time initiative, in 2011. The hefty Axis Mundo catalog makes a substantial contribution to the art historical scholarship, and it provides a rich resource. Beyond the curators’ own well-researched essays, the lavishly illustrated book features seven original scholarly essays. Iván Ramos’s essay examines the psychedelic tendencies in some of Meza’s, Robert Gil de Montes’s, and Carlos Almarez’s work, paying particular attention to the embrace of indigenous, Mexican, and non-Western forms of spirituality in complex and at times appropriative ways. Leticia Alvarado offers a study of the femme performances of Judith F. Baca and Patssi Valdez. Baca, legendary for her community-based mural work, also wittily explored pachuca self-stylization and gender roles in the 1970s. In contrast, Richard T. Rodríguez reads Joey Terrill’s exploration of the macho-presenting homo homeboy figure. The catalog reprints selections from the two issues of Terrill’s Homeboy Beautiful, including the staged “H.B. Exposé” of a homeboy party. Julia Bryan-Wilson surveys the range of conceptual art practices by a number of the artists and collectives in the show, with a focus on Jack Vargas. Colin Gunkel revisits the queer and Chicana/o intersections with the Los Angeles punk scene, with attention to the Bags, Nervous Gender, and Tomata du Plenty of the Screamers. Joshua Javier Guzmán looks at artists’ turns toward abstraction, education, and activism in responses to the AIDS crisis. Macarena Gómez-Barris reads Laura Aguilar’s Plush Pony series as opening up an alternative view of queer and immigrant life that is rooted in trust rather than state surveillance.

Teddy Sandoval, Las Locas, c. 1980. Acrylic and mixed-media on unstretched canvas, 39 x 52 1⁄2 in. Courtesy of Paul Polubinskas. Photo: Fredrik Nilsen.

An alternate title for the catalog might have been Axis Muñoz. The late performance theorist José Estéban Muñoz appears as the most frequently cited scholar in the catalog’s essays; he was foundational to the queer-of-color critique and popularized the concept of world-making as a strategy of survival and life-giving for queers of color. Muñoz wrote, “The concept of world-making delineates the ways in which performances—both theatrical and everyday rituals—have the ability to establish alternate views of the world. …Such performances transport the performer and the spectator to a vantage point where transformation and politics are imaginable.”7 The Axis Mundo exhibition and catalog present these individual artists and their broader cultural tactics as inventing their own alternative worlds (or mundos)—developing their own actual and imaginary institutions, hybridizing mediums, creating fantastical images, collaborating and partying, and sending their work out into the world by mail.

The worlds and networks of Axis Mundo were far from hermetic, and works by artists in the show also appear in a number of other PST: LA/ LA exhibitions, including Radical Women: Latin American Art, 1960–1985, at the Hammer Museum; The Great Wall of Los Angeles: Judith F. Baca’s Experimentations in Collaboration and Concrete, at California State University Northridge Art Galleries; Playing with Fire: Paintings by Carlos Almaraz, at LACMA; Laura Aguilar: Show and Tell, at the Vincent Price Art Museum; and Judithe Hernández and Patssi Valdez: One Path Two Journeys, at the Millard Sheets Art Center, as well as the affiliated installation of Harry Gamboa, Jr.’s Chicano Male Unbonded, at the Autry Museum of the American West. This apparent redundancy demonstrates that queer practices permeate virtually any account of Los Angeles-based Chicana/o contemporary art.

Axis Mundo: Queer Networks in Chicano L.A., installation view, ONE Gallery, West Hollywood, September 9– December 31, 2017. Courtesy of ONE National Gay & Lesbian Archives at the USC Libraries. Photo: Zak Kelley.

Axis Mundo purports to be the first historical exhibition of queer Chicana/o or Latina/o artists. Thus, this exhibition presents recognition of a historically marginalized creative community. As the show demonstrates, these artists collaborated and conversed in wide-ranging ways that often exceeded, refused, or simply ignored essentialist categories. The sheer range of creative practices in this show attests that these artists exemplify contemporary art at large. To say that institutional recognition of these artists is overdue is not enough. This exhibition affirms that curators, scholars, and art viewers—straight and gay—must recognize that artists who have been excluded from the white art establishment have made and continue to make work that grapples with concepts and media in ways as significant as their more canonized white peers.8 Axis Mundo offers an opportunity to reckon with the alternative ways of seeing the world they make possible.

Lucas Hilderbrand is associate professor of film and media studies at the University of California, Irvine, and author of Inherent Vice: Bootleg Histories of Videotape and Copyright and Paris Is Burning: A Queer Film Classic.