1How do maps age? Perhaps they transform as they decay, changing from tools into documents of historical relations, artifacts of visual design, or simply obsolescent curiosities. But such a view misses the fact that a map is always a record of mapping: the process by which foreign phenomena are translated onto familiar grids of intelligibility. Like so many other representations, maps appear to be windows, but invariably alter the objects they claim to transparently depict. The familiarity of the map can thus conceal the traces of formative effects that are sedimented within it, growing less and less recoverable with time.

So if a map’s own contingency and artifactuality are inscribed upon it in a sort of disappearing ink, how might this dynamic become manifest in other forms of spatial knowledge? And in what ways might geography itself as a field be subject to similar forces of constitutive mediation, sedimentation, and drift? These questions assume added pertinence in light of the recent proliferation of geographical forms, techniques, and objectives in contemporary visual art, practices that now appear with a frequency that would have seemed surprising even ten years ago. Tracking this surge in production, a steadily increasing number of exhibitions, publications, and educational programs are dedicated to these “new geographies.”2

Société Réaliste, Ministère de l’Architecture: Culture States, Survey of Former Independent States of 20th Century Europe, 2008. Digital print, 78 3/4 x 47 1/4 in. Courtesy of Société Réaliste.

Like any emergent field, this one is internally heterogeneous, contested, and in flux, and it would be premature, and possibly even counter-productive, to restrictively define it. Nevertheless, one can roughly sketch certain areas of the field by referencing some of its more frequently discussed members. One such constellation might include Christian Philipp Mueller, Emily Jacir, Trevor Paglen, the Center for Land Use Interpretation, and the collaborations of Ayreen Anastas and Rene Gabri. If this group is primarily oriented towards different forms of critical art practice, another, more market-friendly list might comprise names such as Julie Mehretu and Franz Ackermann.

Clearly, how the present horizons of geographical experimentation are defined is significant, insofar as these decisions will inevitably help dictate its future evolution. But a similar urgency should attend efforts to construct a genealogy of the recent “geographic turn.” How, when, and under what preconditions did this shift occur, and what is at stake in its now being largely taken for granted? Could the extreme capaciousness of geography–a category that sometimes seems to include nearly any engagement with space, however broadly defined–conceal substantive differences between practices? And how can critical histories map intertwined transformations in knowledge and cultural production without losing sight of their relation to political economy?

A response to these questions might first consider the decentralized uptake of geographic practices across the postwar neo-avant-gardes in North America and Western Europe. Though the history of this turn remains largely unwritten, many of its crucial features are familiar. One selective list might include Jasper Johns’s refigurations of the United States map; the psychogeographical experiments of the Situationist International; Wolf Vostell’s bus tours of war-damaged European cities; the walks of Stanley Brouwn and Richard Long; On Kawara’s travel postcards; and the proto-photoconceptualism of Ed Ruscha, Robert Smithson, and Dan Graham. To the extent that these geographic impulses within the neoavant- gardes have been registered within art history, they have largely figured as a rejection of prevailing artistic tendencies. For example, Johns’s use of the map is typically regarded as a device to counter High Modernist taboos against explicit content and literal signification; while the neutral automatism of mapping is often thought to have been a means by which Brouwn negated the expressive individualism of painterly mark-making.

While these interpretations have value, they also seem suspiciously convenient, as tidy successions better suited to a textbook than to our actual experience of these works as maps in a peculiar state of decay. Works like Guy Debord’s The Naked City (1957) meant to forcibly derange the city map from its status as a document of hierarchical and centralized urban planning, and refunctionalize it as an agent of drift, a tool paradoxically meant to confound instrumental logic by enabling contingent encounters. This history hasn’t been wholly forgotten. However, despite the trenchant anti-aestheticism they initially manifested, Debord’s maps, now a half-century old, have assumed an abstract, quasi-organic quality. Their gridded fragments have been grafted into what has become an inscrutable network of relays and impulses. They are captivating, reading as static forms that exist just at the threshold of becoming. With their mazes of arrows reproducing the unpredictable self-transformation of thought, they seem to be speaking back to Paul Klee, emerging from a similar terrain of child-savant intensity.3

In such cases it seems that the historical precedents to the new geographies exhibit an obdurate strangeness that current experimental and critical production most often lacks. Whether we think of Debord’s delirious collages, Brouwn’s gnomic transcriptions, or Ruscha’s quasi-autistic catalogs, earlier cartographic experiments tend to retain a certain resistance to interpretation. From a contemporary perspective they appear to us as ciphers or glyphic forms, as decontextualized ruins emptied of their content. No doubt this is partly due to profound structural changes in the function of the map, such that increasing numbers of people worldwide now carry Global Positioning Software (GPS)-enabled phones that give them access to perpetually updated mapping applications, all the while making their own location knowable. From this perspective, it almost seems anachronistic to think of maps as decaying, rather than as being constantly upgraded.

Another possible reason for the apparent distance separating current geographical work from its neo-avantgarde predecessors is that these older forms can be perceived only from the other side of a comprehensive epistemological reorientation. This turn has thoroughly naturalized geographical practices while enabling their increasing sophistication, making earlier experiments seem somehow primitive. Without overly simplifying a complex transformation, it bears noting that the widespread uptake of geography within art has occurred more or less contemporaneously with the ongoing crisis of geography as an academic discipline. For instance, Johns’s American flags were produced shortly after the dissolution of Harvard’s geography department, which signaled a key step in the discipline’s shift away from its original affinities with imperial and colonial ambitions.4

In a series of little-known developments since then, geographical modes of inquiry have not been disbanded so much as dispersed and reorganized into new forms of transdisciplinarity. The most notable exemplars of this shift have been David Harvey and Fredric Jameson, who share much of the responsibility for initiating the “spatial turn” within the humanities and critical theory beginning in the 1980s. Both Harvey and Jameson were and remain committed Marxists, and their analyses have sought to track what were then incipient and are now hegemonic movements of globalization and neoliberalization. It is no surprise that their arguments have influenced numerous radical attempts to hybridize geopolitical analyses with practices developed out of or between any number of academic disciplines, artistic forms, and political practices. One important example of this convergence is Goldsmiths College’s Centre for Research Architecture. Eyal Weizman founded the center in order to train architects in analyzing and managing the political implications of spatial forms, which is a concern that emerges from Weizman’s own work on the Israeli occupation of the Palestinian territories.5 Another is Zones of Conflict, a series of research workshops convened in 2008-09 by T.J. Demos, which brought artists, curators, critics, and theorists together to debate topics including “Transnational Communities” and “Uneven Geographies.”6

But if geography has ceased being a classical discipline and become something more like a distributed tendency, it now manifests the problems of an expanded field. On the one hand, its plasticity has allowed it to engage disparate questions and model new responses.7 On the other, its broadening has inevitably led to a loss of specificity, precision, and possible impact. The more practices that count as geography–and how many can’t make at least some claim to deal with the production of space?–the less they potentially have to say to each other or to us, whoever we are. This dilution could stem from the relative absence of an established mainstream against which to define alternatives. It might also owe something to its reliance on the concept of space, which, like “text” or “art,” is so overdetermined as to harbor incommensurable meanings.

Micha Cardenas, Ricardo Dominguez, Brett Stalbaum and Amy Sara Carroll, Transborder Immigrant Tool, 2009–. Photo courtesy Amy Sara Carroll.

Regardless of its origin, this attenuation of geography poses real problems for any of the wide range of practices that mean to activate its still-considerable potential. Chief among these problems is a diminished analytical power, evident in the widespread reduction of geography to maps or other predominantly visual and static forms of display. Another is the tendency to quietly back away from the issues earlier raised by Harvey and Jameson, many of which–like uneven development, totality, or class–bear a Marxian provenance and still inhabit an unapologetically socialist horizon. Absent any link to political economy, geographies risk lapsing into idealism, becoming the mere negative image of the overly positivistic, so-called “hard” social sciences. A final concern regards the distinction between practices that hybridize techniques, preserving some sense of their respective differences, and those that merely conflate them into a sort of mishmash that is content to stylize information without interrogating it. One needn’t mourn a lost specificity–whether that of a medium or of a discipline–to see this as a problem.

When these issues go unminded, it is all too easy to casually aestheticize and thus obfuscate the obvious, as in the case of The Road Map (2003), a project undertaken by the collective Multiplicity. Charting the results of several trips through the West Bank, The Road Map purported to inform viewers that it takes longer for Palestinians than Israelis to travel through the occupied territories. But who could really be surprised or moved by this? Certainly not any Israeli or Palestinian, or in fact anyone with rudimentary knowledge of this territorial conflict.8 Against this somewhat simple-minded earnestness, one wishes for more work like Francis Alyes’s The Green Line (2005), in which Alyes retraced a portion of the 1948 Israeli-Palestinian border by walking through divided Jerusalem with a leaking can of green paint. There, an action that might first have seemed only to be the literal transcription of map onto territory ultimately assumed much more ambiguous and generative implications when realized.

Such concerns regarding the efficacy and specificity of emergent geographical practices hardly cancel out their potential; if anything, they signal the high stakes in play. They strongly suggest the need for self-critical vigilance, especially as this rapidly evolving territory remains itself largely uncharted. One can thus glean something like an object lesson from the recent exhibition Geography of Transterritories, curated by Hou Hanru at the Walter and McBean Galleries of the San Francisco Art Institute (SFAI). With only five artists participating, the proportions of the show were modest compared to some of Hou’s other recent projects, such as the 2009 Lyon Biennale, or the three-part World Factory, which ran at SFAI in 2007. However, the artists’ diverse working methods resulted in an expansive conception of the operations that might comprise aesthetico-geographical activity, ranging from conducting unscripted interviews to appropriating surveillance footage, inventing typefaces, and executing wall drawings in ash.

Michael Arcega, Concealarium, 2008. Wood, cotton, hardware; 20.5 x 90 x 30 in. (each). Installation view from Geography of Transterritories, February 25–May 22, 2010, Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisco Art Institute. Courtesy of the artist.

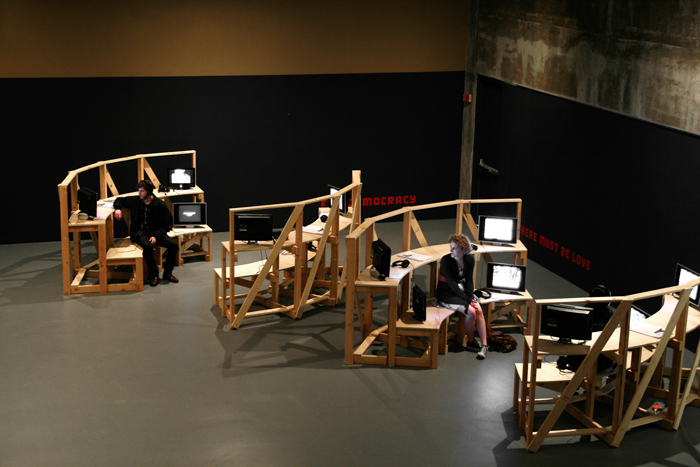

Most of the work on display either hybridized or reinflected recognizable forms. For example, Michael Arcega’s Concealarium (2008) subjected the logic of Carl Andre’s Equivalent series to a wry, neo-Conceptual spin by turning a stack of lumber into a muted comment on immigration politics. Whereas video has basically become the default format for internationally circulating critical art, video works by Ursula Biemann (Sahara Chronicle, 2006-009) and Carlos Motta (The Good Life, 2005-08) adopted unconventional modes of display and address, as if to counter the habituated modes of spectatorship that can neutralize difficult content. Giventhat both pieces depended considerably on interview footage–Biemann’s with North African migrants and Motta’s with residents of Latin American cities–both artists went to lengths to get and keep viewers’ attention, with Motta even building a sort of amphitheater for this purpose. Taken together, the hybridity, interdisciplinarity, and adaptability of the approaches included in the show suggested a shared ambition to trace the contours of spaces that would otherwise be unrecognizable.

Chief among these is the category designated by Hou as the “transterritory,” a site in which traditional notions of nation and territory have been superseded due to the radical transformation of communication, migration, production, and experience. For Hou, the refugee camp exemplifies the logic of the transterritory, with its inhabitants subjected to “constant displacement and transit” as a result of conflicts that fail to recognize established borders. Without minimizing these very real conditions of privation, Hou nevertheless argued that the “transterritorial imagination” could give rise to potentially utopic effects, even as he left these largely unspecified.9

Carlos Motta, The Good Life, 2005–2008. Thirteen-channel video installation. Installation view from Geography of Transterritories, February 25–May 22, 2010, Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisco Art Institute. Courtesy of the artist.

Like many curatorial efforts to respond to contemporary phenomena, this all felt urgent, persuasive, and timely, at least at first. But after further thought, Hou’s model began to seem overly schematic and under-elaborated. Clearly a small show can only do so much, and all the other caveats about the difficulties of curating apply here, too. Even so, it was hard not to question the extent to which all the works shown really exemplified Hou’s concept of transterritoriality. Given that Motta’s interviews concerned the relationships between United States foreign policy and Latin American sovereignty, wouldn’t traditional notions of national sovereignty and regional hegemony have been sufficient? Moreover, it is hard to imagine why a show on transterritoriality didn’t really register the manifold, profound changes this concept has undergone due to recent technological innovations. The obvious site to consider would have been cyberspace, with all the heterogeneity that its everydayness inures us to. Such transterritoriality is by now an unremarkable fact of life for Hou’s affluent audience, through online commerce, virtual communities, and even the clandestinely installed malware programs that turn our computers into remotely controlled pawns in cyber warfare campaigns.

The refugee camp is still a compelling and relevant example, albeit one haunted by the sort of problems that often plague liberal photojournalism, particularly the spectacularization of poverty and the potential for narcissistic viewership. However, it must be acknowledged that the analogy of the camp cannot be universalized, but has only limited applicability outside certain well-defined situations. Moreover, the refugee camp belongs to a historical conjuncture–that of totalitarianism and its aftermath– that predates the show’s problematic by a half-century. Here Hou’s expansiveness tipped over into the sort of dehistoricizing generality that is all too familiar from recent debates around Giorgio Agamben’s theorization of the camp as the actualization of a “state of exception” in which law is suspended. For Agamben, the camp is among the most essential features of Western biopolitics, a tendency that supposedly originated in Greco-Roman antiquity, facilitated totalitarian efforts to manage and exterminate populations, and culminated in American torture and detention policies during the so-called “war on terror.” As many critics have pointed out, this quasi-transcendental, borderline ahistorical argument sits uneasily with Agamben’s stated intentions to undertake a genealogy of the present.10 Hou might have done well to distance himself from such overreaching with a more substantive argument about the historical specificity of his object, linking it to the contradictions of postcolonialism, or to the resurgence of traditional sovereignty in the United States’ response to the 9-11 attacks and the militarized neoliberalism that accompanied it.11 For that matter, one wishes the show had clarified the relation between the transterritory and other established concepts like extraterritoriality (the condition of statelessness first analyzed by Hannah Arendt) and deterritorialization (the process by which Gilles Deleuze and Felix Guattari theorized the relation between cultural formations, place, and immanence).

These issues might seem purely academic, an excuse for so much gratuitous niggling about terminological precision and so on. But phenomena can’t exist outside the concepts we use to make them sensible, and this is all the more so in curatorial practice, where the thematic of a show determines what work appears there and how it is received. Further complications arise when curators draw on philosophical theory, especially since the gallery has become one of the few places where such thinking has a public presence in the United States. Does this activation of critical concepts test, translate, or otherwise transform them? Or does it reify them as consumable commodities within an economy of perpetual novelty? To be fair, this opposition often collapses in practice, and plenty of interesting practices derive from this fact. One thinks here of Thomas Hirschhorn’s uses of text as material, or his role as a self-proclaimed “fan” of philosophers. However, this doesn’t mean that curators should look to theory as a shortcut or an alibi, and it certainly doesn’t excuse them from the work of criticism that should accompany their appropriations.

At issue here is Hou’s rhetoric of displacement and mobility, which sought to aggregate works that might otherwise have seemed somewhat disparate, but stayed too close to the jargon of nomadism that has long pervaded discussions of globalization and migration. Such discourse tends to claim a Deleuzian pedigree, valorizing “flows” and “lines of flight” as it undermines the ontological stability of foundationalisms. In doing so, it seeks to understand emergent phenomena through a conceptual matrix that arguably has more to do with the politics of the French academy circa 1968 than with the present. More troublingly, such debate tends to conflate the circulation of people with that of goods, services, and information. It also often fails to mark the differences between voluntary, necessary, and coerced movement. Tensions between these conditions were evident but largely unremarked at Hou’s exhibition, which risked inadvertently identifying the mobility of wage laborers or political refugees with that of artists and curators on the biennial circuit, an altogether different form of transterritoriality.

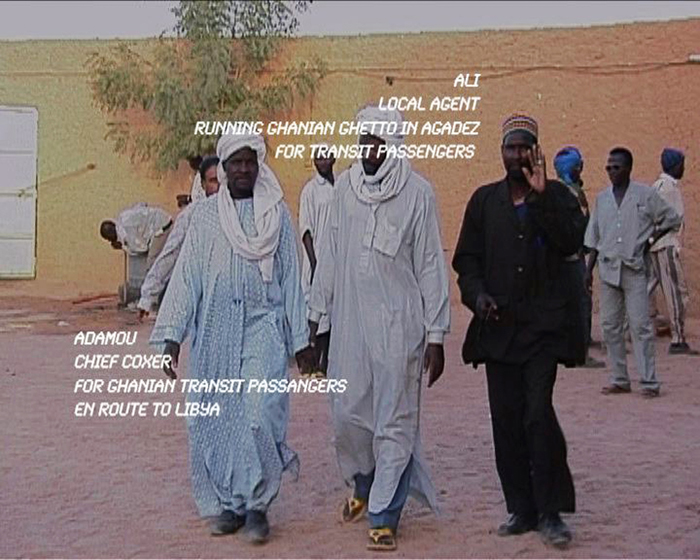

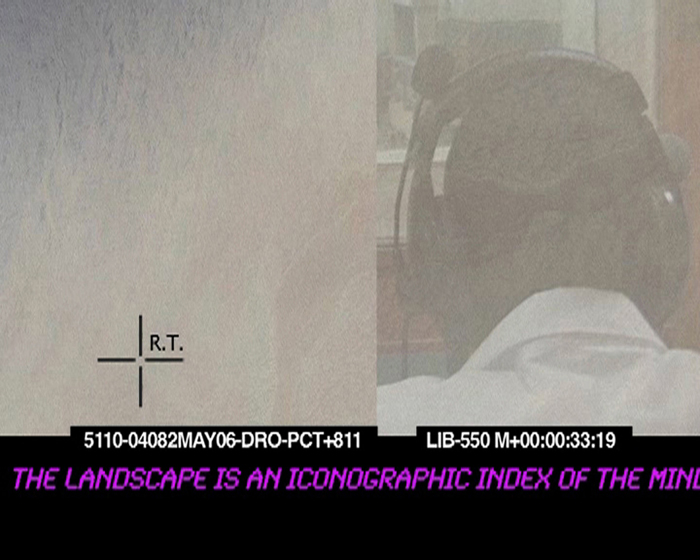

Among the practices surveyed in Geography of Transterritories, Ursula Biemann’s went furthest in exploring the implications of the exhibit’s topic. Her video installation examined immigration to the European Union from North Africa. The Sahara Chronicle linked this issue to the history of the Maghreb, a region in which the tension between nomadic peoples and imperial states long predates European colonization and in fact persists today, with the sovereignty of Western Sahara still in dispute. In this context, transterritoriality is also necessarily a kind of transtemporality, with border patrols using drone aircraft to monitor the movement of prospective migrants along age-old smuggling routes through the desert. Biemann’s piece mixed appropriated surveillance footage with interviews with police, guides, and detained migrants. As if acknowledging the primary importance of research to geography, this work was conducted in remote locations in the Libyan and Sahara deserts and along the Algeria-Morocco border, in sites ranging from bus stations to deportation jails.

Ursula Biemann, Sahara Chronicle, 2006–2009. Video still. Courtesy of the artist.

Against the dedifferentiating tendencies of Hou’s propositions, the Sahara Chronicle represented transterritoriality as a starkly uneven distribution of mobility in which free transit within the Euro zone comes at the cost of increased restrictions for those outside of it. The installation showed how European migration policy has effectively outsourced border control to North African nations, such that the movements of nomadic tribes across the Maghreb well outside the European Union have been curtailed. The piece proved persuasive not only in exposing these systemic contradictions, but also in charting some of the manifold means through which subjects attempt to negotiate these formidable constraints.

Another strength of the Sahara Chronicle was its insistence that geography cannot afford to ignore the extent to which material spaces are constituted by and inextricable from the transitory, virtual sphere of image circulation. In fact, one of Biemann’s chief concerns was to contest the hegemonic representations of EU immigration that dominate the mass media. In this view, migrants aren’t kept from the public eye but instead are sensationally placed before it in countless images of police busts, overcrowded camps, and capsized boats. The Sahara Chronicle meant to counter these effects by incorporating an undefined number of videos, not all of which were shown at once, or indeed ever. Without a story arc, narrator, or other organizing conceit, the installation prompted the viewer to disregard received image-structures and build her own map of the phenomena it represented.

Ursula Biemann, Sahara Chronicle, 2006–2009. Video still. Courtesy of the artist.

Such an approach held that the task of political cinema or video is not to produce the most compelling image, but rather to intervene in existing image flows. However, these intentions were thwarted somewhat by the aesthetics of the actual installation, in which the rawness of the source material clashed with the upscale production values apparently meant to mark its technical or artistic sophistication. The installation’s imposing array of monitors and projections, together with the large, loosely organized range of footage, nudged the work toward a quasi-sublime effect that dulled one’s sense of the imbalances between the conditions of the videos’ production and their exhibition. Such unacknowledged contradictions unfortunately detracted from one of Biemann’s more generative propositions: namely, that critical videography can participate in maintaining a sustainable “aesthetic ecology” by helping map the connections that link seemingly disparate populations in webs of ethical reciprocity.12

Carlos Motta, an emerging artist who was born in Colombia and is currently based in New York, produced another piece in the show with similarly ambitious and well-articulated objectives. For The Good Life, Motta travelled to twelve major cities in Latin America and conducted some four hundred impromptu interviews with pedestrians. He asked the same six questions of his subjects, recording their views regarding the United States’ foreign policy and their own elected leaders, and asking them to speculate about the nature of a truly democratic government. This premise suggested any number of heterogeneous reference points, ranging from ethnographic research and the public opinion survey to direct cinema and underground video. At times the piece resembled recent work by Katya Sander, which foregrounds the unpredictable responses that result from the deceptive complexity of straightforward questions such as: How would you like to be governed?13

The type of exchange that emerges in response models a certain ideal of democracy as an event that can occur anywhere, a contingent encounter between subjects who freely voice their opinions and are thought to possess the same potential aptitudes, regardless of appearances. Citing Aristotle’s Ethics with its title, The Good Life earnestly posited such debate as a component of committed citizenship, reinforcing its claim to a classical lineage by displaying videos in a wooden structure meant to recall the Athenian amphitheater. But where one might have expected this approach to invoke a familiar Habermasian model of rational communication, Motta instead cited the postcolonial activist cinema of Latin America’s Tercer Cine, which looked to film as both an agent and example of counter-publicity. This avowedly radical, agonistic aesthetic helped to balance out the installation’s utopian tendencies. In addition, it reminded viewers of the divergent and intensely contested histories of democratic rule across the region, a history whose specific complexities tend to dissolve when viewed from the North.

Carlos Motta, The Good Life, 2005–2008. Thirteen-channel video installation. Courtesy of the artist.

Ironically enough, given these intentions, one place The Good Life fell short was in more fully surveying this field. One wishes that Motta had travelled from capital cities into the periphery, or had extensively interviewed indigenous populations, as this might have contributed greater diversity of opinion to a work that openly pursued this objective. Similarly, while the installation wisely abstained from simply equating the interview form with democracy, it failed to more rigorously examine the relation between political and aesthetic modes of organization. By making his interviews readily available through an online archive, Motta seemed to be promoting progressive reform through making information accessible to all.14However faultless such intentions may be, they nonetheless appear to conflict with the aesthetic economy that one usually expects from critical art.

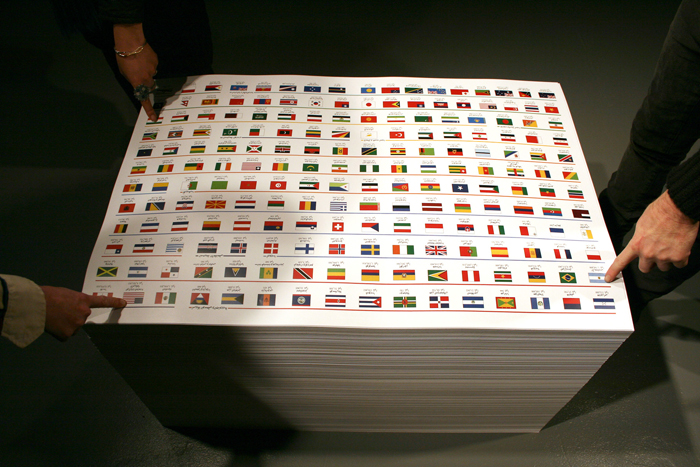

Such a surplus of legible material posed a different sort of problem in the two works presented by Claire Fontaine, the moniker of a Parisian collective who promotes its namesake as, variously, a “readymade artist,” a “nonspecific singularity,” and an “existential terrorist.” As this proliferation of alternate identities suggests, Fontaine knowingly cycles through inherited avant-gardist anti-aestheticisms, with her name ultimately starting to seem like an alias in search of a criminal. Besides generating notoriety, the ostensible point is to locate a viable subject position for resistant action by eliminating spent alternatives. Whereas Fontaine’s polemical writings, available online but not included in the exhibition, suggest numerous ways that her project might work in conjunction with critical geographies, her work at SFAI felt awkwardly inert. Visions of the World (Some Flags) (2010) consisted of a stack of posters depicting a wide array of national flags with country names given in Arabic. Like a clever bumper sticker, you pretty much got it and then forgot it; it lacked any of the pathos or subtlety of the Felix Gonzalez-Torres takeaway pieces it cited. As elsewhere in Fontaine’s work, foreignness was casually equated with an intrinsically resistant alterity without noting the obvious problem of misidentification.15 Circus (2008) was a ceiling drawing of the EU logo rendered from the ash of burnt matches. Absent any larger context of activism, the piece felt like a merely aestheticized gesture of protest, or a refusal of meaning that lacked any meaningful commitment to negative dialectics.

Claire Fontaine, Visions of the World (Some Flags), 2010. Stack of 5,000 offset posters; 36 x 24 in. Courtesy of the artist and Metro Pictures, New York. Installation view from Geography of Transterritories, February 25–May 22, 2010, Walter and McBean Galleries, San Francisco Art Institute. Courtesy of the artist.

Fontaine has argued that the art world functions as a sort of transterritory outside other professional realms, harboring those who choose to become “more or less political refugees.”16 Despite the blatant myopia of such claims, Fontaine raises worthwhile questions by skeptically examining the potential of artistic production to challenge hegemonic divisions between intellectual and material labor. Tracing links between the art industry and the libidinal economy of consumption, she ultimately maintains that the colonization of the aesthetic can only be contested through a tactic she has theorized as the “human strike,” a practice modeled on the public silences of certain Italian feminists in the 1970s.17 However, given that Fontaine has also advocated “political impotence” as both a means and a subject, it was tempting to write off the works she exhibited at SFAI as a cleverly updated version of an old Left melancholy.18

Such cagey equivocations were emblematic of the remaining works in Geography of Transterritories, which indicated important conflicts for critical art production, but only obliquely or inadvertently. Michael Arcega’s Concealarium, consisting of two stacks of unmodified two-by-fours on mobile pallets, presented itself as a return to Minimalism’s encounter with the readymade. Upon closer inspection, viewers found that each structure had a camouflaged door. The hidden compartment within was large enough to hold an adult and thus enable human trafficking, or function as a “panic room.” In rediverting late Modernist art towards more explicitly topical ends, the sculpture resembled Edgar Arcenaux’s appropriations of Sol LeWitt’s wall drawings, or Jennifer Allora and Guillermo Calzadilla’s remake of a Dan Flavin neon work.19 However, Arcega’s piece failed to persuasively register the complexities of immigration politics, and instead seemed to merely cite criticality as an existing style. If anything, Concealarium said more about the fact that artists still often feel as if they have to smuggle critical content into the gallery, or even that they feel compelled to do so.

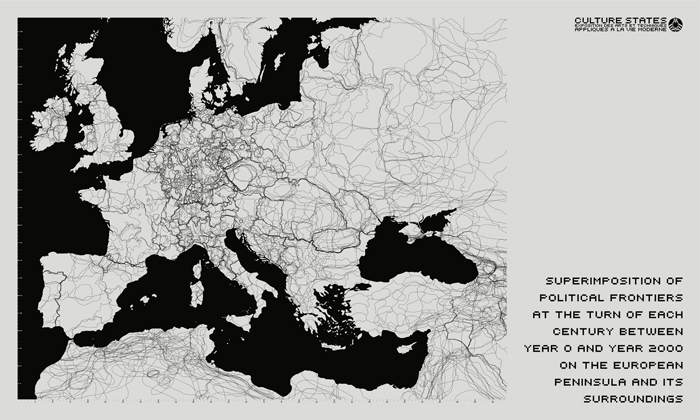

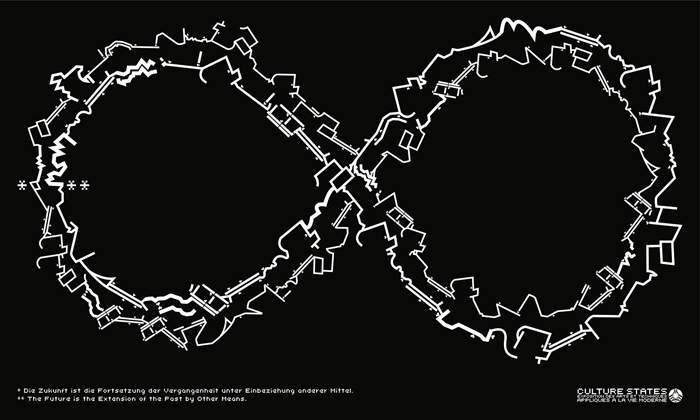

An analogous dilemma arose in the poster series contributed by the French cooperative Societe Realiste. Titled Ministere de l’Architecture: Culture States (2008-09), the work ironically proposed to recreate the famous Paris Exposition of 1937. Societe Realiste subverted the unchecked nationalism of its precedent by including states that no longer exist and mapping minority languages. But despite its intentions to satirize the rhetoric of official culture, the piece often seemed itself an example of precisely this sort of jargon, given its stated objective as a “research and production study in the field of territorial ergonomy.”20 Seeing as the Paris Expo now stands as an example of Modernism’s crisis, one has to wonder how the loss of a shared progressive horizon continues to affect design-based practices, and even whether the overproduction of discourse somehow means to compensate for this lost object.

Société Réaliste, Ministère de l’Architecture: Culture States, The Future Is the Extension of the Past by Other Means, 2008. Digital print, 78 3/4 x 47 1/4 in. Courtesy of Société Réaliste.

Société Réaliste, Ministère de l’Architecture: Culture States, Superimposition of Political Frontiers at the Turn of Each Century Between Year 0 and Year 2000 on the European Peninsula and Its Surroundings, 2008. Digital print, 78 3/4 x 47 1/4 in. Courtesy of Société Réaliste.

Ultimately, such unresolved questions threatened to overshadow the various contributions made by Geography of Transterritories. One left feeling that the works in the show had brought crucial contradictions into focus, but only intermittently, sometimes symptomatically, and without articulating a coherent means of response. In fact, the exhibit itself sometimes fell victim to these conflicts. For example, why did an investigation of transterritoriality only include artists based in the global North?21 Why did it limit itself to the space of the gallery, forgoing any engagement with the singular geographies of the Bay Area? And why did it fail to address the ongoing immigration debates in the United States, specifically those in California? Here one wishes that Hou had acknowledged activist artists such as Ricardo Dominguez, who has worked to minimize fatalities along the United States-Mexico border by distributing GPS-enabled cell phones that are pre-programmed with safe transit routes to prospective Mexican migrants.22

The easy way to resolve such contradictions would be to claim that critical geographies have yet to answer Jameson’s call for forms of “cognitive mapping” that could enable a fractious Left to orient itself relative to the ever-elusive movements of global capital.23 But this would impose a familiar meta-narrative onto a conjuncture that might only seem to be an impasse, one that could allow us to chart new routes that don’t appear on existing maps. Is it really the case that a socialist micropolitics can’t succeed without a concept of social totality? Experimental practices like Biemann’s and Motta’s seem to indicate otherwise. And is mapping necessarily didactic, as Jameson would seem to have it? Exhibitions like Hou’s, despite their compromises, suggest ways that geography can track affective intensities, intuitive impulses, and ethical claims. They also show how mapping can function as a form of negation, gauging moments of resistance. In doing so, they ask that we attend to the ways that aesthetics and politics often interact in what Jacques Ranciere has termed “zones of indistinction,” in which the terms of given aesthetico-political logics are transformed in response to local, contingent antagonisms.24 How can such zones be produced, identified, and mapped? What sorts of experience, community, or contestation do they enable? In order to respond, we would need a geography that we still await, one that could both recognize and affirm the singular space opened by a question.

Andrew Stefan Weiner is a Ph.D. candidate in the Rhetoric Department at the University of California, Berkeley. He has contributed critical essays and articles to Grey Room, Parkett, Afterall, and Qui Parle.